1. Aims and objectives

The context of the project

The original proposal for a research project to address student writing literacy was developed by a group of heads of departments at Kakariki College, (a decile 2 co-educational ethnically diverse suburban secondary school in a main urban centre) who were concerned at the level of students’ achievement in writing within their school. The teachers recognised that NCEA assessment has increased the significance of written language within the senior secondary curriculum, making attaining national qualifications, regardless of subject specialisation, dependent upon competency in writing. This shift is reflected in the national initiatives for building the literacy capability of teachers and learners, such as Effective Literacy Strategies in Years 9-13 (Ministry of Education, 2004) and the Secondary School Literacy Initiative, which demonstrate an increasing interest in the intersection between student literacy and educational outcomes. Before this project, the school had already made a commitment to the national drive to improve literacy standards, with an inhouse professional development initiative entitled ‘What Works’, which was supported by a school advisor funded by the Secondary School Literacy Initiative.

At Kakariki College there was also statistical and anecdotal evidence to suggest that the writing competency of students was a barrier to their attainment of NCEA, even beyond that of students in similar schools. In 2004, 54.8 percent of students assessed at Level 1 achieved the eight literacy credits necessary for the full qualification; the national average for a decile 2 school was 61.6 percent. However, a survey of staff undertaken by the school claimed that the students do bring strengths to writing (e.g. confidence in writing genres that are close to oral traditions) and that many students are interested in improving their skills. A meeting of heads of department at the school demonstrated a desire on the part of staff to work with these strengths and improve writing literacy amongst Kakariki College students. The school submitted an expression of interest to the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI), with feedback that suggested that this was a valuable endeavour; however a more coherent research focus was required. Input from the School of Education at the University of Canterbury enabled the development of a more sophisticated research design and conceptual framework, and Kakariki and the University of Canterbury School of Education were jointly awarded funding for the research project.

The input of the university researchers stretched the school’s focus on writing achievement outcomes to develop a research proposal that acknowledged the complex issues surrounding raising student literacy achievement within the context of low decile ethnically diverse secondary schools. Recent international literature on schools with a similar demographic suggests that literacy itself is a complex construct, and that secondary content area literacy learning and its use are particularly so (Moje, Ciechonowski, Kramer, Ellis, Carrillo, & Collazo, 2004). Addressing student literacy achievement is also challenging given that school knowledge and discourses, which tend to be aligned with the knowledge and discourses of white middle class families, clash with knowledge and discourses that diverse learners bring from their home and community knowledge bases (see Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Moje, Collazo, Carrillo, & Marx, 2001).

While this study, and its attempt to develop writing pedagogy, was a response to an assessment driven curriculum, Nuthall (2001) challenges teachers and researchers to look beyond normative assessments as conclusive measures of learning and therefore teaching. It was the intention of the overall study to examine the impact of the programme on student achievement in formal assessments of learning (e.g. AsTTle, NCEA), yet the researchers are mindful that these assessments need to be examined in the light of the variables that can impact on student achievement. Some of these variables include: the disjuncture between school knowledge and discourses, and the knowledge and discourses of students (Moje et al., 2001); the extent to which students’ expectations of their capacity for success play an important role in engaging them in school and learning (Akey, 2006); the industrial production-line model of schooling which tends to privilege normalcy in relation to academic achievement (Gilbert, 2005), especially in terms of narrowly defined, academic constructions of literacy (May, 2002); teacher and school expectations of diverse learners (Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003; Moje, 2002), and the cultural realities of classrooms as a sites of learning (Nuthall, 2001; Quinlivan, 2005).

While it is of critical concern to this study to understand how Kakariki College might build a culture of high achievement and expand possibilities for students, it is also important to understand what challenges may stand in the way of this aim. Of particular concern to the researchers are the social inequalities that impact on the achievement of Kakariki students, including the specific challenges faced by Māori, Pasifika, and learning support students. To address these issues a group of university researchers, in liaison with curriculum and professional development leaders from the school, worked with four classroom teachers to examine (a) teachers’ practices and students’ experiences of the teaching and learning of writing, (b) how teaching and learning practices intersect with teacher and student locations within sociocultural frameworks and, (c) the possibilities for teacher interventions revealed by this investigation.

Research evidence on building and sustaining literacy practices is consonant with aspects of the literature on successful school reform. Successful literacy practices in schools are dependent on ‘… a deep and broad understanding of literacy and its implications across the curriculum, coupled with active leadership strategies that support literacy (such as by the principal, LL [literacy leader], heads of department/faculty)’ (Wright, 2005, p. 4). However, as Brodky (1996) and others (McDonald, 2006; Moje et al., 2004) suggest, notions of literacy are complex and highly contested, and current constructions of literacy tend to reflect the dominant ideologies of the time. Despite the best intentions, the enactment of school literacy work risks becoming narrow and instrumental within a neo-liberal climate that increasingly values competitive individualism (Davies & Saltmarsh, 2007; Street & Street, 1991), or solely academic constructions of literacy (May, 2002). As we shall show, attaining congruence of a deep and broad understanding of literacy amongst the school, university and School Advisory Service research participants became a challenging prospect.

So while Wright’s (2005) model may be an ideal, changing practice is recognisably fraught, with many challenges to be overcome by school reformers (Gunter, 2001; Tyack & Cuban, 1995). The outcomes of this project have included recognising the extent to which the complex discursive make-up of schools, and their location within diverse social, cultural and economic communities, may inhibit as well as enable teachers’ interventions in student achievement (Moll, VelezIobanez, & Greenberg, 1989). Despite these challenges, this project generated a valuable evidence base that reveals some of the kinds of teaching practices that could support the specific literacy needs of Kakariki students through valuing students’ cultural locations (Phillips, McNaughton, & Macdonald, 2001; Bishop et al, 2003), the funds of knowledge students bring from their home, peer, and community networks (Moll et al., 1989), and engaging in relevant and meaningful discipline rich learning contexts (Comber & Nixon, 2006; Moje, 2002). Our research also indicates that teachers’ engagement with this evidence base and associated research literature, as well as the processes they each undertook in their individual classroom projects, have resulted in changes to their thinking about writing pedagogies and, in some cases, changes in classroom practice. In addition, members of both curriculum leadership teams and the newly formed distributed leadership team within the school have committed to ongoing discussions and workshops with the university researchers to explore ways in which the research findings can be useful in informing the improvement of teaching and learning practices in classrooms within the school.

Aim

The aim of the pilot study was to investigate the possibilities, in a low decile multicultural school, for teachers to improve student learning outcomes through writing. This was to be achieved through teacher research and through theoretically informed professional development.

Pilot study objectives

Specifically, the original objectives were to:

- provide baseline data for a longitudinal study that drives future practice of a whole-school writing initiative (including teacher learning) and evaluates the impact on outcomes for students through investigating teacher and student perceptions and experience of learning, writing competency, achievement, and student diversity (particularly with regard to Māori, Pasifika, and students with identified learning needs)

- trial, refine and evaluate a cross-disciplinary professional development programme for secondary teachers founded on best evidence for professional learning, sustainable reform, and effective practices for teaching subject-specific writing by embedding four teacher-researchers and their case study research on writing literacy within an existing professional development initiative at the school.

However, in the early stages of the project, the link between the teacher researchers and the existing school professional development was severed, and the first objective and the case studies with accompanying teacher professional development through classroom-based research became the central work of the project. In the case study research the teachers developed individual subject-specific research questions related to writing, in response to student data and their own practice needs (see Table 10).

A third objective emerged as the researchers undertook an investigation into the dynamics that lead to the severance between the TLRI project and other school professional development initiatives.

- To make an account of and find some means to negotiate the challenges of embedding research-informed practice within existing professional development at the school.

2. Research design and methodologies

Research design

In recognition of the long term and challenging nature of affecting student learning outcomes and undertaking school reform (Tyack & Cuban, 1998), the pilot study was embedded within a larger longitudinal project to be developed concurrently with the pilot study (see Appendix A). While the pilot study was initiated as a standalone project, it was also intended to act as a catalyst for further school reform.

The pilot study centred on engaging a core group of four Year 10 teachers in a model of professional development designed to build the research and teaching capacity for subject-specific writing programmes within the school. Within the pilot, this model was intended to be developed, trialled, refined and evaluated for use across the whole school in 2007. It was also to be used as a source of research evidence (using both research literature and the situated research evidence collected by the university researchers) for a whole-school professional development programme running alongside the research.

The focus of the pilot study was to build capacity among the four teacher researchers, investigate classroom practices in-depth, and develop a situated model of professional learning. The longitudinal project was intended to locate the reforms at Kakariki College within existing research evidence on school-wide reform, teacher professional learning, subject-specific writing literacy in secondary schooling and their relationship to student achievement through a combination of macro-contextual statistics and in-depth field data collection and analysis. A combination of research methods would enable the development of a complex picture of the relationships between school interventions, student achievement and sociocultural location. The collection and analysis of statistical evidence was initiated during the pilot; however the statistical analyses most significant to the aims of the overall longitudinal project was intended to occur outside of the scope of the pilot study.

In the first half of 2006, the university researchers developed a proposal for a longitudinal study using University of Canterbury funding. However, on the advice of the school leader on the research project team, the newly appointed school principal made the decision not to proceed with the longitudinal study before the 2007 TLRI funding round closed in the first half of 2006.

The foci of the pilot study

The project was conceived as having three foci—a research focus, a professional development focus, and a writing literacy programme focus. Each of the foci was intended to inform the structural design of the pilot study and the roles that the participants played in the initiatives undertaken within the school.

Research Focus. The research focus of this pilot was centred on a group of four teacher researchers who worked with the university researchers to research their own practice with regard to the subject-specific teaching of writing. Drawing on action research paradigms, the teachers developed research questions informed by student perspectives and the teacher’s research interests that related to the connections between student achievement and the teaching and learning of writing appropriate to their subject (see Kemmis & Wilkinson, 1998; Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003 for examples). These investigations were intended to be used as the basis for the development, implementation, and evaluation of a whole-school programme of subject-specific writing for Year 10 students. The teacher researchers contributed to the development and trial of each of their research questions within the context of their writing programmes in a Year 10 classroom. It was intended that the teacher researchers would be supported by the resources of the school’s ‘What Works’ professional development programme, fellow teacher researchers, the project team, and student researchers, along with input and guidance from the university researchers.

Professional Development Focus. The professional development aspects were tied to building the capacity of the teacher researchers. The school contributed some funding to teacher researchers’ involvement in the project from their professional development budget. It was the intention of the project that the professional learning of the teacher researchers would in part be supported by the expertise of the university researchers. It was also envisaged that the action research projects undertaken by the teacher researchers in their Year 10 classrooms would significantly build on, and contribute to ongoing literacy professional development initiatives that were already under way within the school through the teacher researchers’ situation within the ‘expert group’, facilitated by the school’s specialist classroom teacher and a member of the external school advisory service who was funded through the Secondary School Literacy Initiative.

Writing Literacy Programme Focus. The programme focus of the pilot was to be centred on the teacher researchers’ development of their own subject-specific writing programmes based on preexisting data within the school (including a heads of department survey, asTTle data, NCEA results, writing exemplars) and professional development facilitated by the university researchers. The results from the research focus of the project were designed to feed into the whole-school professional development programme, with the teacher researchers and project team contributing to facilitating the development of a whole-school writing programme for 2007.

Methodologies

The structural design of the pilot study

The structural design of the pilot study comprised a group of nested and interlocking initiatives within the school (see Appendix B). The pilot study was designed to use the findings from the case studies to inform, build upon, and expand existing professional development initiatives within the school. The core operations of the pilot study were to be coordinated by the project team comprising members of the school community and university researchers.

The project team

The role of the project team was to collaboratively drive both the research and professional development initiatives within the school related to the project. Members of the project team combined the resources and expertise of university researchers with Kakariki personnel’s knowledge of professional development, curriculum, and educational leadership within the school. The project team comprised three school members; the head of the English department who initiated and developed the original TLRI expression of interest, the school leadership team member with responsibility for professional development, and the specialist classroom teacher who was involved along with a member of the School Advisory Services in the implementation of the National Literacy Initiative within the school (Ministry of Education, 2004)[1]. The two lead university researchers, Ruth Boyask and Kathleen Quinlivan, were also members of the project team.

The group coordinated both the research and practice components of the project. It was intended that leadership within the research project be taken up by members of the project team on the basis of expertise and interest. The work of the project team was supported by an advisory group who met with the project team to provide input and guidance. Members of the advisory group comprised university educational researchers, educational consultants, and a manager of the College of Education School Advisory Service. The project team met with the advisory group three times over the course of the project, with the school principal joining us for the final meeting.

The teacher researcher group

The work undertaken by the teacher researcher group formed the core focus of the pilot study. The group of four Year 10 teachers, representing a range of subject areas and ability groupings, opted to take part in action research projects to learn about, develop, and trial approaches to develop students’ subject-specific writing literacy. It was intended that professional development support for the teacher researchers would be provided through their participation in the school’s ‘expert group’, or the project team as had been planned. This did not eventuate, for reasons outlined in Section Three: Project Findings. A series of ongoing one day workshops, facilitated by the university researchers, was implemented as an alternative means of support. At these workshops, the teacher researcher group discussed diverse issues that affect educational achievement and issues in subject-specific writing literacy such as how students learn, and how teachers can facilitate learning in the classroom (Nuthall, 1999, 2001) making connections between school literacy and students diverse social worlds and understandings (Bishop, Berryman, Tiakiwai, & Richardson, 2003; McCarthey & Moje, 2002; Phillips et al., 2001), and what it means to be a writer within their subject areas (Comber & Nixon, 2006; Moje et al., 2001).

Throughout the first two terms of 2006, the teachers reflected upon data gathered by the teacher researchers regarding the experiences of students and the teacher’s own beliefs. Informed by the data findings, and in collaboration with the university researchers, the teacher researchers developed research questions that were appropriate to their subject discipline (Moje et al., 2001) and drew on the expertise and knowledge of their students (Moje et al., 2004; Moje, 2002), and the teachers’ own interests. The teachers then developed a subject-specific writing programme for their Year 10 class that they trialled with their students in Term 3 of 2006. At the suggestion of the university researchers, support from the school advisory service for the classroom trials was offered to the teacher researchers. One teacher researcher took up the offer, while the other two chose to rely on researcher feedback. The resultant intended and unintended learning of both teachers and students was reported to the university researchers in Term 4 of 2006.

Over the course of the year, the teacher researchers participated in a professional development programme designed to build teaching and research capacity. Facilitated by the university researchers, the programme was designed to support the development of subject-specific writing programmes undertaken in the classroom with students.

School-wide professional development programme

While the professional development focus of this pilot study centred on the trial and refinement of a professional development model for teachers within the teacher researcher group, a second aspect of the study was to generate research findings from the teacher researcher group that could inform the implementation of a whole-school professional development programme. This was to be supported through the school’s provision for professional development. The research evidence collected in the pilot study was intended to inform the programme for 2006. It was envisaged that the programme for 2007 would be developed in consideration of issues arising from the pilot study research report. However this possibility did not arise because the school declined to participate in the longitudinal study. An analysis of the challenges that faced the project in drawing on the classroom teacher classroom studies to inform the development of school-wide professional development, and using the existing professional development networks within the school to support the teacher researchers in the classroom, is included in Section Three of this report.

Ethics

The research project gained the ethical approval of the University of Canterbury ethics committee. Informed consent consistent with the ethical conventions of qualitative research practice was gained from all participants in the project including members of the project team, the principal, the teacher researchers, and the student participants and researchers (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003). The participants had the right to withdraw at any stage of the project. One member of the project team chose to do that, citing work pressure. The confidentiality of participating teachers, students, and the wider school has been protected through the use of pseudonyms. Members of the project team will have the opportunity to respond to the draft of the research report before it is produced in its final copy. As much as possible, approval will be sought from the participants before the data is used in a public sphere.

Demographic information

Kakariki College is a decile 2 co-educational ethnically diverse suburban secondary school in a large urban centre. The school has a roll of 796 students: 48 percent New Zealand European/Pākehā; 33 percent Māori; 10 percent Samoan; 5 percent Asian and 4 percent ‘other’. Boys comprise 52 percent of students and girls 48 percent. In 2006 55.5 teachers (FTTE) worked within the school.

Since October 2004, the school has been under limited statutory management. Over the time that the research proposal was developed, and in the early stages of the research project, the school was being led by a caretaker principal. The newly appointed principal took up his position at the beginning of Term 2 in 2006.

The demographic features of the participants can be seen in the following tables.

The Project Team. The four school members of the project team (Table 1) represented a range of school management, curriculum management, professional development and classroom teaching experience and expertise. Unfortunately, attempts to invite representatives from Māori and Pasifika communities on to the team were unsuccessful.

| Pseudonym | Position | Ethnicity | Age | Time at School | Years Teaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph | Assistant Principal with responsibility for professional development |

Pakeha | Over 40 | 5 | 20 |

| Phillip | Principal | European | Over 40 | 1 year, 1 term | 27 years teaching, 13 of those in leadership roles |

| Heather | English, Media Studies teacher. Specialist Classroom Teacher. |

NZ European | Under 40 | 5 years | 5 years |

| Sue | Head of Department English |

NZ European | Over 40 | 15 years | 15 years |

Teacher Researchers. Four teachers self-selected to become teacher researchers (Table 2). They represent a range of subject areas, length of teaching experience, genders, and time teaching at the school.

| Pseudonym | Class & subject area | Ethnicity | Age | Time at School | Years Teaching |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jill | 10 Blue Social Studies | New Zealander | Under 40 | 1.5 years | 7 years |

| Joanna | 10 Red English | New Zealander | Over 40 | 15 years | 15 years |

| Gina | 10 Yellow PE | New Zealander | Under 40 | 3 years | 3 years |

| Garry | 10 Green Science | New Zealander | Over 40 | 8 years | 9 years |

Student Interviewees. Between 7 and 10 students from each of the participating Year 10 classes were interviewed by the researchers (Tables 3–9). The students were interviewed in small friendship groups with attention given to ensuring a range of genders and ethnicities, and a range of achievement levels and perspectives on writing, across each class sample.

10 Blue Social Studies is streamed in the top ability band, based predominantly on their literacy and numeracy results, and was the second highest of the six Year 10 form classes. However, anecdotal comments from teachers at the school suggested that many of these students were in this class as a result of overall declining standards in basic literacies at the school rather than their particular achievement.

| Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathy | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Tiresa | Samoan | 14 | F |

| Doug | Australian | 15 | M |

| Peter | NZ European/Irish | 15 | M |

| Edward | NZ European/Irish | 15 | M |

| Natasha | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Anna | NZ European | 14 | F |

10 Green Science: 10 Green, a Year 10 Science class, met for four periods a week. 10 Green was streamed officially as a mid-band ability class, based predominantly on their literacy and numeracy results. However in practice, it functioned more as a low-mid band ability class because of the number of lower ability band students moved into the class. Of the 23 students in the class, seven were girls, one of whom identified as Samoan, three as Māori and three as New Zealand European. Of the 16 boys, three identified as Māori, two identified as Samoan, one as Māori/Tongan/New Zealand European, and 10 as New Zealand European.

| Student Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roger | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Jake | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Laura | NZ European/Irish | 15 | F |

| Fono | Māori / English / German / Tongan |

15 | M |

| Iris | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Dan | NZ European | 15 | M |

| Mathew | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Shirley | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Jade | NZ European | 15 | F |

10 Yellow PE: 10 Yellow PE was a composite of the female students from two Year 10 form classes, because it was a policy at the school to divide physical education classes into male and female groups. This meant that half of the class was from a low ability band Year 10 class and half of the class was from a mid ability band Year 10 class. 10 Yellow PE met for two periods a week. All of the 19 students in the class were girls. Four identified as Samoan, two as Māori, one as Chinese, and 12 as New Zealand European.

| Student Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marilyn | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Fiona | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Salofa | Samoan | 15 | F |

| Kate | Samoan | 15 | F |

| Roslyn | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Petra | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Hine | Māori | 15 | F |

| Hanna | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Victoria | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Gloria | Samoan | 14 | F |

10 Red English: 10 Red English met four periods a week. It was identified as in the top band Year 10 class, along with 10 Blue; however, it was referred to as ‘the extension class’ and it was generally recognised by students and teachers that 10 Red was the top Year 10 class. Of the 23 students in the class, 16 were girls, one of whom identified as Tongan, three as Māori, and 12 as New Zealand European. Of the seven boys, one identified as Māori and six as New Zealand European.

| Student Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amy | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Eve | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Rachael | Cook Island Māori | 15 | F |

| Ben | NZ European/Māori/ Samoan |

14 | M |

| Michael | NZ European/Māori | 15 | M |

| Joseph | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Gen | Māori | 14 | F |

| Vicky | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Anita | NZ European | 15 | F |

Student Researchers: Small groups of students from each of the Year 10 classes volunteered to act as student researchers in the project. The numbers in groups varied across each class, and changed over the course of the year as the composition of classes was altered.[2] The greatest number of student researchers who volunteered came from 10 Red, the top band English class. The student researcher groups provided ongoing feedback to teachers and the researchers over the course of the classroom projects.

| Student Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peter | NZ European/Irish | 15 | M | |

| Edward | NZ European/Irish | 15 | M | |

| Student Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roger | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Jake | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Student Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gen | Māori | 14 | F |

| Vicky | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Ben | NZ European/Māori/ Samoan |

14 | M |

| Michael | NZ European/Māori | 15 | M |

| Joseph | NZ European | 14 | M |

| Amy | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Eve | NZ European | 14 | F |

| Anita | NZ European | 15 | F |

| Tiresa | Samoan | 14 | F |

Baseline data collection and analysis

Data collection

The focus of the baseline data collection was developing a comprehensive picture of teacher professional learning and student writing literacy within the school. Data were gathered from student, teacher, and management participants within the school. A range of different methods was used in order to understand the complexities of the interrelated practices from a range of participants’ perspectives. Qualitative semi-structured (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003) tape-recorded face-to-face interviews were initially undertaken with the four participating teacher researchers. Students in each Year 10 class were initially surveyed through a questionnaire in order to gain a general impression of their perception of themselves as writers, and the issues that they considered important in relation to writing in their subject areas. On the basis of the questionnaire responses, qualitative semi-structured face-to-face tape-recorded interviews were undertaken with up to 10 students from each class. In order to gain varied perspectives on writing within each class, the students represented a range of achievement levels and demographic locations. The students were interviewed in small friendship groups with attention given to ensuring a range of genders and ethnicities across each class sample. Participant observations also were undertaken by the university researchers in each of the four case study classes.

The data were transcribed, and then thematically coded and analysed by the researchers using standard qualitative methodologies (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003). The researchers and teacher researchers worked together to consider and discuss the findings in the light of student relevance (McCarthey & Moje, 2002), and the teacher researchers’ own professional interests and expertise (Eraut, 1994; Hodkinson & Hodkinson, 2003). Data findings were presented to the students in each class, with opportunities for feedback provided. As a result of discussion and feedback from both teachers and students, four research projects were the focus for the case study (see Table 10).

| 1. Social studies | Do students’ research report writing skills develop by conducting a research project that is relevant and meaningful to students in Social Studies: ‘What Would Your Ideal School Look Like?’ |

| 2. English | Are students’ sense of themselves as capable, confident, and well- motivated writers increased through developing ‘writing buddy’ skills in providing high quality peer feedback? |

| 3. Science | Can students’ confidence and ability as scientific writers be improved through engaging in relevant and meaningful scientific learning processes? |

| 4. Physical education | Originally the area of investigation planned was ‘Exploring the use of personal journal writing as a strategy to encourage writing that is relevant and meaningful to students in PE’. However in response to student resistance to participation in the project, this was revised to ‘What does it mean to be a writer in PE?’ |

The analysis of the baseline data was also fed back to the project team members, and the newly appointed principal. There has been no opportunity as yet to feed back the analysis of the baseline data to the newly established professional development working party, or to whole staff during professional development sessions. However, as a result of discussion on the draft research report, a group of curriculum and educational leaders have expressed an interest in working with the researchers to explore the implications of the project findings for teaching and learning in the school. This will be occurring in Term 3 of 2007.

The trial of writing strategies in the case study classrooms

The four teacher researchers (science, social studies, English and physical education) implemented writing innovations at the beginning of Term 3, 2006 in response to the initial data findings, student feedback, reading on learning and literacy in their subject areas, and their own professional interests. In response to overwhelming feedback from physical education students, who indicated that they were unprepared to participate in a project to trial a subject-specific writing programme, the research in this class shifted focus to investigate pupil resistance to writing in physical education. Despite deciding against the full implementation of her writing strategies, the physical education teacher chose to remain involved in the project. The other three classes continued to introduce writing strategies into their programmes throughout the term.

A variety of data collection methods were used to capture the complexity of the classrooms from a range of student, teacher, and researcher perspectives. Forms of data collection included classroom participant observations undertaken by the researchers and the writing of teacher and student research journals. Student researchers within each class provided feedback to the researchers over the course of the projects. As a result of classroom observations undertaken by the researchers, researchers gave feedback and made suggestions to the teacher researchers when it was possible.

Professional learning and development within the wider school

Operating since 2005, the expert group was an existing, flexible grouping of teachers supported by the Secondary Schools Literacy Initiative to develop and trial evidence-based strategies for enhancing student learning within the school, and it had been identified by school project team members as the natural home of the project. However, despite a promising start, attempts to create connections between the TLRI project and the school-based professional learning expert group were unsuccessful. The failure of the project to establish this link meant that while the project could continue its work within individual classrooms, its potential to gain leadership support for the teacher researchers, and have a wider professional development impact within the school, was considerably reduced.

In the absence of this link, the university researchers suggested to the project team that time be devoted to understanding why an alignment between the interests of this group and the TLRI project was difficult to develop and maintain. In response to the severance of the link between the TLRI project and the expert group, semi-structured tape-recorded face-to-face interviews were conducted with the project team and followed up by interviews with both the school facilitator of the expert group and the leader of professional development within the school. Repeated approaches were made to Teacher Support Services leaders of the expert group once it became clear that connections between the classroom-based research and professional development networks in the school were not going to eventuate. While meetings between the university researchers and key personnel at the advisory service, including the advisors supporting the expert group, revealed some of the tensions that had led to this severance, interviews with the Teacher Support Services were not forthcoming and these issues remain outside of our legitimate data collection. Despite the challenges, these meetings did open productive discussion on the development of protocols for working with school advisors and led to the offer of support from subject advisors for the teacher researchers on their individual classroom projects.

Development of the longitudinal research proposal

As is indicated in the original research design, in mid 2006, the researchers developed a longitudinal research proposal in order to build on the work undertaken in the 2006 pilot study. Acting on advice from the senior management member of the project team, the newly appointed school principal made the decision not to proceed with a longitudinal study within the school, citing disjuncture between the school and university vision for the project. After the school’s withdrawal from this initiative, project team member Joseph, who held the senior management portfolio for professional development within the school, reduced his involvement in the direct management of the pilot study.

Follow-up data collection and analysis

Data collection

Follow-up data collection was undertaken, in the first instance, to gain an understanding of both the intended and unintended outcomes of participating in the classroom-based research projects from both teacher and student perspectives. In addition, interviews were conducted with school leaders and teachers to further understand the challenges that arose in establishing supportive links between the classroom-based research projects and wider professional development initiatives within the school.

The university researchers conducted follow-up semi-structured tape-recorded face-to-face interviews with the teacher researchers and selected groups of students from each the three Year 10 classes participating in the classroom research projects to trial subject-specific approaches to writing. The university researchers undertook classroom observations in each Year 10 class.

Writing samples were collected from the four targeted Year 10 classes. The Centre for Educational Measurement’s (CEM) attitudinal test, SATIS, was administered in both Terms 3 and 4 across the whole of Year 10 as part of the data collection.

The university researchers conducted follow up semi-structured face-to-face tape-recorded interviews with the assistant principal who was responsible for professional development within the school, and also with the school principal and the specialist classroom teacher.

Data analysis

The gathered data has been coded and analysed thematically using standard qualitative research methodologies (Bogdan & Biklen, 2003). This analysis has been drawn on in the writing of the final research report. Teacher researchers, members of the project team, and the school principal have been provided with the opportunity to provide feedback on the analysis presented in the research report.

3. Project findings

This section presents the research findings from the pilot study. In light of the complex design of the project, and the deviation from the intended programme of research upon the school’s withdrawal from the longitudinal initiative, the data findings are presented in the following three parts. First, we look at the initial data findings that generalise teaching and learning practices of Year 10 at the school. These are the outcomes of the baseline data findings that were presented initially to the teacher researchers, then students in each of the case study classrooms, and finally to senior management within the school. These data findings informed the direction of the teacher researchers’ projects in each of the four case study classrooms by assisting them to develop research questions and develop interventions to address their individual agendas for improving student writing. It was also the intention that this baseline material would be part of an empirical database that would be used to assess the outcomes of the longitudinal study (along with school achievement data). It was on production and dissemination of these initial findings to the project team and the principal that the school decided to withdraw from the longitudinal initiative, citing that the agenda of researchers was not satisfactorily aligned with the school’s goal of improving student writing. However, they have since been re-presented to senior management at the school in the form of synthesised diagrams. Recent discussions at the school indicate they will be used in upcoming discussions between curriculum and school leaders and teacher researchers within the school.

Second, the data findings reveal what was achieved in the four case study classrooms. This project was designed with the specific intention of encouraging teacher researchers to address issues that they perceived as important within the context of their subject area, the particular class make-up, and their own teaching identities. As intended, this resulted in four quite different projects, which ultimately achieved four different outcomes. The university researchers have attempted to situate the teacher researchers’ findings within a more detailed analysis that makes connections between student outcomes, teacher findings, and research literature relevant to improving writing literacy in a low decile school. The university researchers suggest that this section in particular provides a valuable evidential base on the possibilities open to teachers for improving teaching and learning practices, such as the teaching of writing, within secondary school classrooms.

The final section was developed in response to the challenges that this project presented to both the school and university partners and explores the limitations of the research project. Throughout the study, both partners have suggested that while initially there appeared to be common ground in the development of the project, its enactment brought to the surface discrepancies in the capacity to engage with the processes and purposes of educational research. The university researchers suggest that these discrepancies arise because practices of both researchers and teachers are constructed within sociopolitical economies of knowledge. According to conventional literature on research partnerships, productive relationships are dependent upon mutuality and consensus (Robinson & Lai, 2006; Timperley & Robinson, 2000). However, others suggest that conflict is also an inevitable marker of the social production of knowledge (Avis, 2005; Davies et al., 2007; Stronach & McNamara, 2002), since knowledge and power are distributed differently amongst partners. Examination of these dynamics reveals the complexities that may emerge within research partnerships, as well as indicate possible means for their negotiation (Quinlivan, Boyask & Carswell, 2006).

Baseline data findings

The baseline data findings relate to the Year 10 students’ and teachers’ experiences of learning and writing in social studies, English, physical education, science and other subjects at Kakariki College.

Adolescents are engaged in identity building, an active process that occurs in response to the different contexts they operate in and the relationships they forge within them. Our research sits within recent literature that suggests that identity construction is both a social and psychological process (May, 2002; Moje, 2002; McCarthey & Moje, 2002), indicating that students’ individual psychologies and, in the case of this research project, capacities to write, are developed dialogically within their social milieu. However, research that examines the microcontexts of classrooms suggests that not only should teachers be cautious in overgeneralising the extent to which identity development occurs in relation to large and powerful social institutions such as schools, churches, and the justice system; in fact, the bigger and more meaningful influences may be through interpersonal relationships formed in peer, family, and community networks (Clark, 2006; Nuthall, 2001; Lingard & Mills, 2002; Moll et.al, 1989, Moje et.al, 2004). This body of research supports transforming school practices as well as the teaching and learning relationships that underpin them, so that school learning becomes more meaningful, is more equitably distributed, and has greater influence on the identity building of secondary students.

However, we would suggest the dialogic nature of this process means that unless interventions are carefully and strategically planned, interpersonal relationships and personally relevant experiences are largely determined by cultural norms and the conservative sociopolitical impulses that sustain them (see Cole & Scribner, 1974; Lave & Wenger, 2001 on the primacy of social structure and practice in determining psychologies). Within a low decile school like Kakariki College, where the percentage of the roll to achieve qualifications from the National Qualifications Framework was approximately half the national average in 2005 (NZQA, 2007), teachers evidently have wide discrepancies to overcome between the experiences and values of their students, and those required to be successful at school (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Moll et.al, 1989). Whilst there are broader debates to be had regarding success and achievement within the current political economy (see Boyask et al., forthcoming June 2008), successful interventions require overturning the entrenched norms of what recent literature and policy describes as ‘underachievement’. Student data from the school suggests that low achievement in schooling may be related to low level of interest, and consequent value that students attribute to their experience of school. Interviews with Year 10 students at Kakariki College indicate that for some students, school, and its culture, is almost entirely foreign and meaningless:

| Ruth: | What about things that you’re interested in outside of school? What are the types of things you are interested in firstly? |

| Shirley: | What do you mean? |

| Jade: | Yeah. |

| Ruth: | Are any of them related to school? |

| Jade: | Just hanging out with your friends. |

| Shirley: | Shopping |

| Jade: | And that’s about it really |

| Ruth: | So you don’t have any interests that might be related to schoolwork? |

| Jade: | Not really. |

| Shirley: | Not really. (Interview with Shirley and Jade, 17 March, 2006) |

Both of these students were in a low/mid band class, frequently truant and regularly in contact with the school’s disciplinary system. Ultimately, one was required to leave the school.

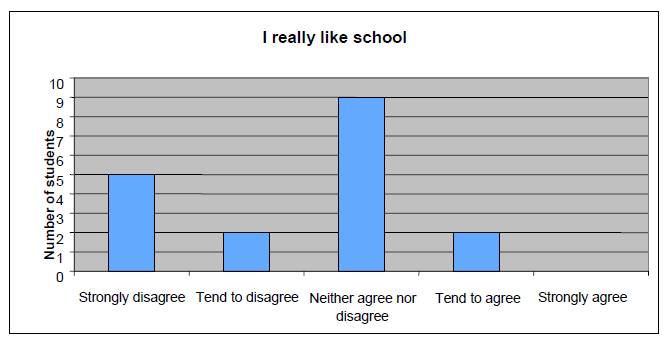

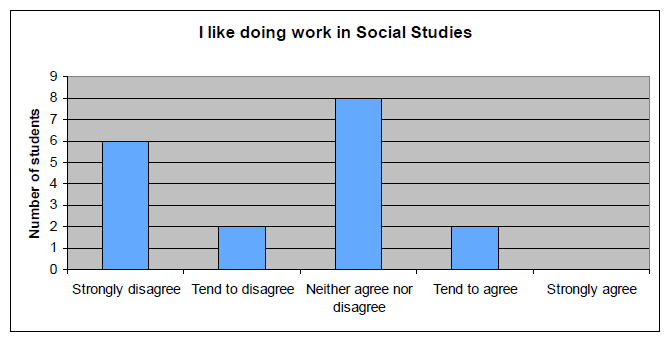

More successful students have identities that mesh with school norms as they are defined in both the macro and micro settings of schooling (e.g. policy context, school-wide setting, classroom setting). Current features of a ‘successful student’ include one who is literate, compliant, works hard, achieves well in tests, is articulate, and forms relationships that assist in being successful (see Wylie, 2004; Ministry of Education, 2006). In view of the banding system at Kakariki College, and the low number of students within the school who conform to the norm of success, ‘successful students’ are most likely to be in the top band class. Students in this class indicated that their teachers appeared to be resting their hopes for achievement in national qualifications on this class. This is supported by data from the Centre for Educational Measurement (CEM) SATIS test that was administered at Kakariki College in Terms 3 and 4 as part of the baseline data collection for this study. Results across the four Year 10 classes under study indicate that students in the top band class were more likely to like school, feel that they belonged at school, and believe that they would stay on at school after Year 11 (see Appendix D).

Our own survey of the students (see Appendix C for the questionnaire) also indicated that there was a significant difference in how the four classes perceived themselves as writers. Within the top band, most of the students in the top class (10 Red) enjoyed writing and thought they were either sort of or good at writing. The second to top class (10 Blue) had very poor perceptions of themselves as writers, with all but one student thinking that they were not good writers and only one student indicating that they enjoyed writing. The class 10 Blue was also distinguished through the SATIS data as the class who least liked school, adding quantitative support to our assertion derived from qualitative data. Overall the SATIS and questionnaire data support our claims that within student perceptions there are close relationships between teaching, learning, writing, and the attribution of meaning and value to schooling. It is apparent in all of our data collection that the practice of banding is reinforcing social norms of success for the top band class, albeit a more complex picture than straightforward reproduction, and limiting possibilities for those in lower band classes (for comparable research see Quinlivan, 2005). We explore these dynamics and their effects in the following analysis of student data.

What makes a successful student?

The premise that writing competency can be enhanced in conjunction with students’ appreciation and value for schooling is an identifiable entry point for the development of teaching interventions. Through interpersonal interactions, adolescents develop value for institutional practices, like the ones schools provide access to (e.g. learning opportunities, attaining credentials, and better life chances). This value develops when there is some congruence between their sense of self and the prevailing norms of the institution. As Amy suggests;

| Kathleen: | Well, how would you rate her expectations for you? |

| Amy: | I think they’re very good. It could improve writing for me. I really like to write stuff in my own time and that. And that could improve that as well. I feel like this year could really help me out.(Interview with Amy, 14 March, 2006) |

But this meshing is not straight forward. Students are diverse in terms of interests and values. Students who are successful at school negotiate school norms in different ways from each other, let alone from their less successful peers. For example some are better at some subjects than others because the logic or practices of these subjects are more congruent with the students’ identities (see Boyask, 2003; Gee, 2004; Moll et al., 1989; Moje et al., 2004). Secondary schooling has always presented a challenge for school improvement initiatives at least in part because traditionally less emphasis has been placed on interpersonal relationships between student and teacher than in primary schools. Initiatives such as Te Kotahitanga have attempted to strengthen that bond through emphasising the importance of student—teacher relationships (Bishop et al., 2003). However, research on the role of student interest in increasing motivation for learning and enhancing performance would also suggest that a shared subject interest is one of the most profound strengths of secondary teaching (see McPhail et al., 2000; Isaac, Sansone, & Smith, 1999). Of course, this presents significant challenges for students who are not interested in the subjects that school has to offer, or whose interests may lie in marginalised areas of the curriculum.

The baseline data suggested that those students who are currently disengaged from school show a discrepancy between the identities they are crafting for themselves and those valued within normative understandings of schooling. As Peter indicates:

| Peter: | Other people are the brainy ones, eh. They want to do good; they want to get somewhere and that. That’s fine. But different people—different objectives in life.(Initial Interview with Peter, March, 2006) |

Despite the fact that ‘braininess’ and its association with success in school qualifications and therefore life opportunities is not always the cultural norm of Kakariki College students, evident through their performance in national qualifications, students still associate schooling with academic enquiry. Students can become disengaged when they think that school is for other types of people. Students who find school more challenging to their identities are also more likely to not comply with school regulations. However, they are less likely to have agency in how they negotiate these regulations, because while they can take recourse in resistance, ultimately power to remain successful in the terms of the school is dependent upon complying with the regulations. It appeared that the disengaged students’ primary form of resistance was to find ways to be successful that were not valued within school norms. As Eve and Amy explain:

| Eve: | People assume that … going against authority is kind of like the cool thing. |

| Amy: | I guess they don’t actually want to learn about this sort of stuff. There are a few students in the class that actually want to learn about writing and how to improve our writing and you know, think, but a lot of the people don’t care. (Interview with Amy and Eve, 14 March, 2006) |

Students’ attempts at feeling successful and enhancing their status amongst peers in these terms appear to limit the possibilities of making use of what school could offer them. Edward suggests:

| Kathleen: | Can I ask you a question and you can be honest about this: Is—do you feel— how do you see yourself as being successful at school? |

| Edward: | Not really. Just the way I am. I would have been successful if I was. I was in Year 6 and Year 7. When I went to Year 8 just changed eh. I just got into the habit of not doing any work. I can’t get back to the way I was. (Initial Interview with Edward, March, 2006) |

Since it also remains the case that the majority of relationships formed at school are with peers, peer culture has a very significant influence on how students develop identities and commitments (Nuthall, 2001; Quinlivan, 2005; Wexler, 1992). Peers help to sustain norms of ‘success’ amongst their friendship groups, whether that is success as it is valued within the school or alternatively how it is valued amongst their peer groups. Jake and Roger explain:

| Kathleen: | And you know these groups, do they all work differently in terms of the work that you do in class? |

| Jake: | The cool people don’t get any work done … but the quiet people usually try to get their work done. But with me and Roger … the in between kind of normal group, we get just enough work done. |

| Roger: | So you can get out of class. |

| Jake: | We still do our work. But we don’t do excessive amounts. We just do what we need to do. (Interview with Roger and Jake, 13 March, 2006) |

Powerful learning opportunities can arise if teachers take advantage of the meshing of peer culture and school values (Moje et al., 2004). The following two students are in the top class, indicating that the school has recognised them as successful learners qua writers; however, both Eve and Amy explain that it is the writing that they do and share among themselves that provides the most meaning for them:

| Eve: | I don’t like reading authors’ books as much. I like reading what people my age have written because it’s got—it’s more relatable for me. And you know, I would rather read people’s emotions than something like a textbook. |

| Amy: | We would personally like stories and stuff. Read each others’. Give it to each other to read … you know it’s hard to find a book about what you really want to read about, but when you’re writing it yourself or something of your good friends it makes it a lot funnier too. |

| Kathleen: | That’s interesting. So what you’re telling me, then, is that you actually show each other your writing. And does that help you write better, or how does that influence your own writing? |

| Eve: | Yeah, it does influence, because I know that people are going to read it so I think more deeply about what I’m writing. In classes I probably could do my work better writing wise, I just write whatever I don’t really think about it as much as I should because it’s not really relatable—the work. (Interview with Amy and Eve, 14March, 2006) |

The university researchers suggest that taking cognisance of students’ opinions on what they find meaningful is a very productive starting place for teachers who are looking to change their own practice. As others also claim, it provides a source of evidence that can be reflected upon in order to develop types of practices that may address the contextually specific needs of classrooms (Bishop et al., 2003; Moje et al., 2004; Nuthall, 2001; Quinlivan, 2005). In this sense, the baseline student data from this project provided a specific source for the teachers within the school, demonstrating how teachers can use research to support the development of their teaching. Student interview transcripts can be analysed for examples of teaching practice that have either aided or hindered their learning. In Table 11, the university researchers carefully selected some of these instances, particularly examples that could be related to writing literacy, and linked them with premises derived from social theory and psychological theories of learning (Alton-Lee, 2003; Comber & Nixon, 2006; Moll et al., 1989, Moje et al., 2004). These were presented to the teacher researchers at the second of their professional development days, as a source of discussion, and for them to consider the implications of students’ experiences of schooling for their own teaching practice.

| In terms of cognitive development | |

| Relevance is made transparent to students | Amy: …whoever I talk to about algebra that I’m learning right now they say it’s useless. What are we going to use algebra for? Replacing a number with a letter and making it more difficult and more complicated. Kathleen: Does your teacher ever make any connections to you about how algebra’s related to the rest of the world? Amy: No. We learn how to do algebra but we don’t actually learn about how it’s related to … I think if there was a – if you knew the reason behind whey we’re learning it would make it a lot simpler and easier work. (Interview with Amy, 14 March, 2006)Doug: He writes the learning outcomes on the board, and we’ve gotta write them out. But I don’t, they take up too much paper …He’s like ‘write this down’ ‘ok’, so I pretend I’m writing, but he doesn’t notice that I’m not. Amanda: Yeah. Why don’t you write them? Doug: ‘Cause it’s pointless. Amanda: Yeah? Doug: I’m never gonna read them back to see what my learning outcomes are. They only need to be on the board. (Interview with Doug, 17th March, 2006) |

| When teaching recognises and builds on students prior knowledge and experiences | Kathleen: So you feel quite comfortable in being an achiever…? Rachael: Yeah, ‘Cause I love achieving things. ‘Cause last year – I just did an achievement last night. There’s this girl that runs – she’s like the fastest in the grade. And then, I’ve never beat her and then last night I beat her. Kathleen: And would you talk about any of that with your teachers? Rachael: Nah. Vicky: Teachers that want to listen, you would. Rachael: Yeah. (Initial Interview with Rachael and Vicky) |

| Linking students’ cultural resources into their learning programmes | Kathleen: Do you think reading helps you write? Ben: Yeah, in a way. It can give you some new words as well. Like, when I was reading through some scriptures or parables and stuff out of the satanic bible on the Internet. You look at the word and you’d be: That’s an interesting word. And you look it up on Dictionary.com and then sometimes I use those kinds of words. Kathleen: That’s interesting aye? (Interview with Ben, 14 March, 2006) |

| When cultural practices (like writing) are made transparent and taught | Amy: I think there are a lot of things that we need to learn that a lot of people take for granted and think we can learn by ourselves but really, we can’t. We actually need help. But I guess they don’t realise unless you tell them I can’t do this on my own I need to learn how. So I guess it’s partly our responsibility to tell them that we have to still be pushed to learn how to keep ourselves on task but you know anything. (Interview with Amy, 14 March, 2006) |

| Ways of taking meanings from text, discourse, numbers or experiences are explicitly taught | Jade: The literacy thing I didn’t quite get, s/he didn’t really explain it enough for me. And I was kind of like, lost on it. We had a test. We had a test and I didn’t really know what to do. It was really confusing. Shirley: Sometimes his/her stuff doesn’t really get into… Jade: Yeah like doesn’t make sense, like doesn’t explain it properly. (Interview with Shirley and Jade, 17 March, 2006) |

| New information is linked to students’ experiences | Kathleen: So what would you suggest about how [your teacher] could teach that subject in a way that hooked you in and got you interested? Do you think it’s possible? Edward: Not really. Kathleen: Is that because you’re not interested in geography and history and the subjects? Both: Yeah. Peter: Our lifestyle’s like physical work. We have to be moving, outside, chucking a ball, playing rugby. That’s what we do. We don’t like sitting there writing a book … (Initial Interview with Peter and Edward) |

| In terms of social processes | |

| Use of collaborative peer friendship groups that enable group processes to facilitate learning | Eve: Well some teachers who actually take the time to get to know us better do understand the groups and they do like when they’re saying can you do this work in groups of whatever they’ll make it flexible so that people can be with their friends. But some teachers, like, don’t take the time to get to know us and they don’t really care about the groups and they’ll put you – I think sometimes I work better with the people that I know because I don’t feel pressured. Amy: Yeah, like it’d be a lot harder for me if I was to work with a bunch of not – I wouldn’t say strangers but you know, kids – like, unlike me in a way. I’m not pushing myself away and calling myself different that much but yeah, I think it’d be a lot easier to work with friends. (Interview with Eve and Amy, 14 March, 2006) |

| Caring and support in the interactions and practices of teachers and students | Rachael: I find it enjoyable how she got the principal in to … Vicky: Yeah. Rachael: … talk to us about all the things. Vicky: A big group discussion. Rachael: But our class was too shy to stand up and say something. We just thought we were blank in the head, we had nothing to say. Vicky: He’s coming back though. Like, we’re telling him what needs to be improved in the school and how it’s a good place here and stuff. Kathleen: And so why do you think that it’s good that the principal, how does that help you learning when the principal comes into the classroom? Vicky: Shows that he cares. About students’ opinions. (Initial Interview with Rachael and Vicky) |

| Teaching practices value and address student diversity | Kathleen: Yeah, so you find – do you do that subject? Michael: I did it last year. I did it like crap. Ben: He didn’t like the teacher. Kathleen: Oh, really so you like the subject but you don’t do it. That’s a shame, eh. What was it about the teacher that was so bad? Ben: She treated black people bad. Michael: Yeah. Kathleen: You’re joking. Ben: Yeah it was funny ‘cause she was treating me bad, him bad and all the black kids in the class bad. Michael: And one of them swore at her and just left the class. Ben: And when she saw my mum – ‘cause my mum’s white – she started treating me better – after the interviews so I thought that was a bit weird. (Interview with Michael and Ben, 14 March, 2006) |

| Recognizing the interdependence of academic and social norms | Rachael: Kind of ‘cause we see goals that we want to achieve at school and like outside of school…I want to save for a car. And get a car by the time I get my restricted. Kathleen: Wow … that’s pretty amazing. And you think you’ll be able to do that with the money that you earn from your job and stuff? Rachael: Yes. Kathleen: Cool. And what about your school aims and stuff like that? Rachael: To go right through school and pass all my exams. Kathleen: So you want to be academically successful in terms of NCEA and stuff like that. (Initial Interview with Rachael) |

As the university and teacher researchers discussed the baseline findings, we posited that making classroom writing activities more personally relevant for students may encourage them to be more willing to take the risks associated with writing. In line with prevailing research on the importance of interest for motivation, we considered that classes where there was a bigger discrepancy between student identities and normative constructions of success may require more deliberate and careful attention to establishing and sustaining interest in writing activities (McPhail et al., 2000; Isaac, Sansone & Smith, 1999). Our student interviews clearly indicated that many students at this school are not interested in writing. Other research suggests that motivating students to write is made more difficult when students do not see writing as connected to their interests and identities, because shifting their achievement also requires shifting their sense of identity so that it includes writing (Moje et al., 2004). However, the same students who professed no interest in writing also recognised that their writing was better when it centred on their existing areas of interest and engagement. There were also some responses from students that suggested new areas of student interest could be fostered by teachers. These responses from Kakariki students provided both evidence and suggested some means for enhancing connections between student interests and classroom writing activities.

The university researchers’ contended that the students’ reluctance to write was a consequence of the power that is invested within writing as a school activity, perhaps even more intensely than other forms of forms of school work. Its enactment provides material evidence of students’ competence and ability. While its status varies within specific cultural contexts, and is evidently diminished in some of the students’ own subcultures, writing occupies a singularly high status position within schooling. However, as the teachers who initiated this project had found, this is profoundly problematic in a low decile school such as Kakariki College. A critical analysis explains why Kakariki students struggle with writing literacy. Their social situation within a school and community with low socioeconomic status largely determines their schooling outcomes and achievement (see Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Nash, 2003). Low decile schools reproduce existing social stratification because they are embedded within communities where there is limited cultural capital required for schooling success. In this situation, low self-esteem in relation to writing may seem inevitable because students genuinely do not have the resources to succeed. Rather than accepting this structural explanation as an admission of defeat, both the university and teacher researchers were committed to better understanding the barriers students encountered, with the intention of developing personally significant strategies that could intervene in the social reproductive function of schooling at the level of the individual, thereby offering students possibilities for producing new cultural and social outcomes.

Whilst the subcultural and peer groups revealed in student interviews were evidently engaged in their own forms of cultural production, ethnographic data from the case study classrooms collected before the teacher researchers’ interventions revealed that writing activities set by teachers generally supported the reproduction of existing social norms within the school and wider schooling culture. For example, participation in writing for authorised learning and assessment purposes required a significant commitment that many were reluctant to attempt.

During an initial observation within one of the mid-band case study classrooms, Ruth noted the following during a classroom activity where students were asked to complete a worksheet by answering a series of four questions in their books:

Two girls seated near me write in their books with pink and purple pens. One of them has a pink pencil case. Two more girls enter the class, 35 minutes late and join another at the back of the room. They don’t get any work out. The girl near me rips out the page she’s been working on and screws it up. Her friend follows suit. One of them begins writing the title of the work on a new page, but then starts to leaf through the rest of the book. She rips out the corresponding page of the one she’s just ripped out. This time they don’t write down the questions, only the answers, but in 10 minutes they have only written two one word answers. The teacher comes over to the girls and talks to them about the third question, which requires a whole sentence answer. They never complete it. The two girls who arrived late still have no work in front of them. One of the girls near me keeps flicking to the front page of her book where there is one full page of beautifully neat blue handwriting with headings underlined in red. But now she has still only answered the two questions (10 Green Field Notes, 27 February 2007).

All of the girls observed here were identified by their teachers as having problematic behaviour and a lack of motivation for learning. The problematic features of their writing literacy are certainly dominant in the narrative; however, we also looked for the possibilities for participation in writing embedded within this story. Did the girl who repeatedly turned to her beautifully written page derive pleasure and pride from her work? In a later interview, one of the girls who did not even attempt to write talked about her aspirations for the future:

Well I want to go to university, but nah that probably won’t happen (Jade interview 17 March 2006).

Talking to Jade about her future suggested that she was quite aware of the discrepancy between what she thought education could do for her, and what she was actually prepared to undertake at school. While she was almost convinced of the unattainable nature of her desire, she was still open to its possibility. Many of the student interviews revealed similarly high aspirations. As this observation of Jade and her classmates suggests, while students’ desires may not be apparent through their writing, they may be accessible to teachers through other means, such as observation or conversation. Paying attention to students’ desires rather than their performance, can shift our understandings of their identity and motivations, and has the potential to change the way that teachers relate to their students, and in doing so, perhaps shift student outcomes.

The other element we considered in this phase of the project was teacher researchers’ own understandings of the teaching and learning of student writing within their subject area. At the third teacher researcher professional development day, teacher researchers were given a summary from their own interview transcripts to add to the evidential-base from which they designed the research agenda for their classrooms. Table 12 shows the summary statements the teachers received.

| Jill | Is concerned that students do not strive to achieve beyond what they consider to be ‘just enough’ despite teacher expectations that all students are engaged in work related activity.

Frames students as similar within all school settings, and thinks that the same issues and challenges for teachers arise regardless of socioeconomics, ethnicity, and culture because what all schools have in common is a focus on results. |

| Joanna | Expresses commitment to two pedagogical visions, both teaching as a technical endeavour, using scientific processes for the teaching of writing (where teachers are accountable for managing student achievement efficiently), and using a creative, caring and responsive pedagogy that acknowledges student diversity and expertise.

Suggests that the school is quite traditional in its curricular, pedagogical and administrative functions. |

| Gina | Has a strong moral motivation for teaching, based on own experience of being a disadvantaged learner.

Wonders about using practical activities as a tool for students who respond well to physical activity to enable them to develop their literacy skills. |

| Garry | Has a strong belief in a vocational function for schooling, particularly learning appropriate work behaviours.

Has a focus on basic literacy in class, rather than specific content knowledge. |

The university researchers believe that the combination of teachers reflecting on their own beliefs and values, how these are interpreted by others (i.e. the university researchers) and how they are experienced by students has the potential to produce profound pedagogical shifts. While we hoped to find evidence of these shifts throughout the project, measurable outcomes were significantly limited through the school’s withdrawal from the longitudinal initiative. Similar efforts suggest that significant and sustainable change would require longer and more continual effort than allowable through this pilot study (McPhail, 2006; Tyack & Cuban, 1995). However, the following section that looks more closely at the prevailing pedagogies, students’ classroom experiences, and the changes that occurred through participation in the project show some results that are quite encouraging.

Four classroom case studies

This part of the project findings reports upon the four classroom case studies, and discusses the process and outcomes of the case study research agendas. While these analyses draw upon the teachers’ own findings, these were orally reported to the university researchers who have written the final report. This has enabled the university researchers to situate the individual research concerns of the teacher researchers (evident through the individual classroom research questions identified in Section Two of this report) within a wider analysis of the intersections between personal relevance and interest and the development of writing literacy in a low decile school. In some respects, this approach to analysis is an outcome of the context of the project. This was a small-scale pilot study that was intended to be the start of ongoing work within the school. The classroom effects were inevitably limited because of the short time frame allowed for the interventions (one term), and the limited support provided to the teacher researchers as a result of turbulence and uncertainty in the project, school professional development, and leadership. However, it was important for the project to develop rich findings despite limited classroom effects to support the ongoing work of the school. The university researchers have attempted to do this by situating the case study findings of the teacher researchers within the collective knowledge of critical literacy, multiliteracy, and teaching and learning research. For the university researchers, this highlights the importance of acknowledging the expert roles that both teachers and university researchers bring to research partnerships.

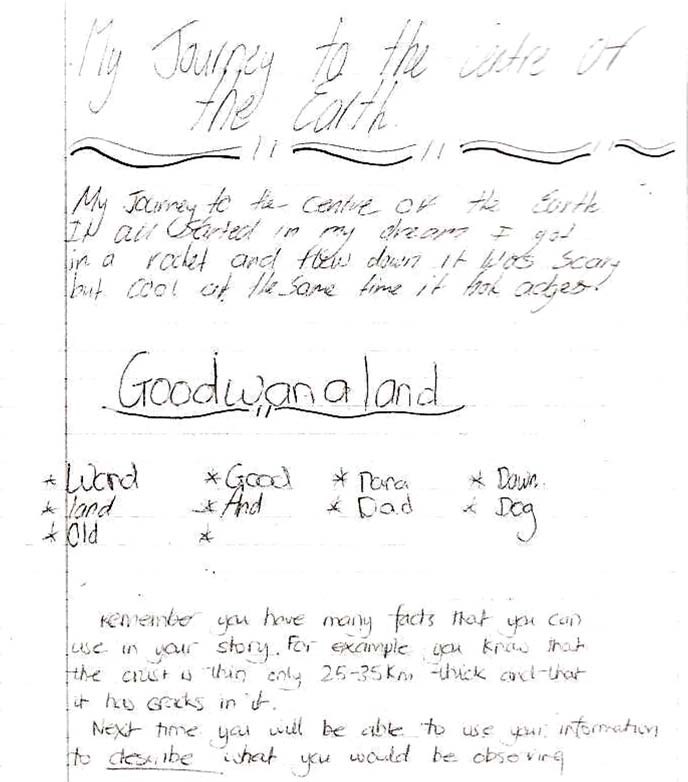

Case study 1: Writing as a personally relevant activity

The concern to develop classroom practices that supported student interest and personal relevance was an idea picked up by the teacher researchers within each of the four case studies. In particular, Jill, the social studies teacher, decided to focus her study on the implementation of a unit of work that was intended to be relevant and meaningful to a class where many of the individuals appeared disengaged and disruptive to the learning of others:

Can students’ research report writing skills be developed by conducting a research project that is relevant and meaningful to students in social studies: ‘Students exploring what they would like their ideal school to look like’?