Background (why we did the research)

Human displacement is currently at the highest level internationally since World War II. According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR, n.d.), the number of displaced persons has increased by more than 70 percent since 2011; in mid 2022, there were 103 million forcibly displaced people worldwide. Of these, 32.5 million were refugees, and only 42,300 were resettled. Over a third of displaced people (36.5 million) were children aged under 18 years. The 1951 UN Convention for Refugees and 1967 Protocol on the Status of Refugees define as a refugee someone who “is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted ….” (UNHCR, 2010, p. 3). Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) is one of about 37 countries internationally which accepts an annual quota of refugees under the Convention, via the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Currently, the annual quota stands at 1500. Although this is small by global standards, NZ prioritises women at risk, people with medical needs or disabilities, and emergency protection cases (Mahony, Marlowe, Humpage, & Baird, 2017). A smaller number of ‘convention refugees’ also come to NZ through community sponsorship and family reunification programmes, and as asylum seekers. Notably, from 2020-2022 (the duration of our project), NZ did not meet its quota commitments due to the impacts of COVID-19.

Resettlement for quota refugees is guided by the Refugee Resettlement Strategy (Immigration New Zealand, 2012, hereafter, ‘the Strategy’), which identifies five priority outcome areas for resettlement: health, education, housing, participation, and self-sufficiency. The stated aims of the Strategy are to deliver “better outcomes for refugees settling in New Zealand, including: increasing the number of refugees in paid employment, increasing their educational achievement, and reducing their long-term dependency on welfare services” (Immigration New Zealand, n.d.-b). At the time of writing, the Strategy is undergoing a ‘refresh’.

Following arrival in NZ, quota refugees participate in an Auckland-based five-week residential orientation programme at Te Āhuru Mōwai o Aotearoa – Māngere Refugee Resettlement Centre (MRRC). The programme includes an orientation to life in NZ, English language tuition, health screening, and the provision of mental health support (Immigration New Zealand, n.d.-b). Children and young people attend an onsite school and early childhood centre. Following the programme, people are relocated to designated ‘resettlement centres’, where agencies are contracted to provide 12-24 months of resettlement support.

As a signatory to the 1951 Convention on Refugees and later (1967) Protocol (UNHCR, 2010), NZ has committed to providing people granted refugee status “the same treatment as is accorded to nationals with respect to elementary education” and “treatment as favourable as possible, and, in any event, not less favourable than that accorded to aliens generally in the same circumstances, with respect to education other than elementary education” (p. 24). People granted refugee status become ‘permanent residents’, and children and young people can legally attend school until 21 years of age. However, refugee-background students are not named as ‘priority learners’ in education policy, and access to targeted supports, including specialist English language teaching, varies by geographical location and educational institution. Targeted support provision depends on the initiative of regional Ministry of Education staff and institutional leaders (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala, & Mostalizadeh, In press; Sutton, Kearney, & Ashton, 2021). Funding for specialist language teaching is limited (Rafferty, 2020), and wider inequities inherent in education provision impact on refugee-background students. Refugee-background secondary school students with less than five years in NZ schools experience poor educational outcomes (Rafferty, 2020; Rafferty et al., 2020), severely limiting their post-school options.

Policy gaps and lack of policy integration can compound for refugee-background students, creating further barriers to education (O’Rourke, 2011; UNESCO, 2017). For example, inflexible secondary school pathways or lack of academic opportunity, combined with limited language-learning support, can set students up for failure and limit their post-school options (Anderson et al., In press). Examples of inflexibility include schools’ refusal to support students’ access to academic opportunities beyond English language learning, or failure to tailor curriculum for students’ learning needs (see Anderson, Mostolizadeh, Oranje, Fraser-Smith, & Crampton, 2023; Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala & Mostolizadeh, 2023). Broken educational pathways and language-learning requirements can necessitate longer, less linear routes to and through tertiary study, which is problematic alongside confusing application processes (UNESCO, 2017) and stringent student loan and allowance requirements (O’Rourke, 2011).

The UN describes education as an ‘enabling right’, since access to education enables access other human rights (Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action, 2015). Access to tertiary education promotes a sense of belonging (Wilkinson, 2018), enables social and economic integration and equality (Dryden-Peterson & Giles, 2010; Hynie, 2018; Lenette, 2016; Wilkinson & Penney, 2021), and equips people to contribute to the rebuilding of communities post-conflict (UNESCO, 2017). ‘Settlement countries’ also benefit socioeconomically when citizens from refugee backgrounds can access tertiary education (Lenette, 2016; Ramsay & Baker, 2019). Graduates from refugee backgrounds often use their expertise to support their own communities, and/or to contribute to resettlement contexts as community leaders (Baker, Ramsay, Irwin, & Miles, 2018; UNHCR, 2016).

The NZ Refugee Resettlement Strategy (Immigration New Zealand, 2012) largely conceptualises education in terms of English language learning. The Strategy’s stated education outcomes indicator is an increase in “refugee school leavers with five years in the New Zealand education system achieving NCEA Level 2” (p. 7). However, this qualification is not accessible for people who are too old to attend school when they arrive in NZ, and it does not provide access to degree-level programmes (Anderson et al., 2023). The Strategy does not appear to envisage tertiary study as a pathway for people from refugee backgrounds.

Our project proposal was developed in 2018 by a cross-sector group engaged in advocating for refugee-background people in Dunedin who sought to access tertiary education. Our rationale was both pragmatic and scholarly. Pragmatically, Dunedin and Invercargill became refugee resettlement centres in 2016 and 2018 respectively, and a growing number of young people in local secondary schools were keen to engage in tertiary education. While some of the region’s tertiary education institutions were actively involved in education provision for ‘mature’ newly resettled refugees (for example, English language tuition), less liaison had occurred at the school-tertiary education juncture. Our project was intended to inform practice and support provision in this regard. With respect to its scholarly rationale, our project was also informed by the outcomes of a preliminary study in 2018, which found that refugee-background university students who came to NZ towards the end of high school faced challenges establishing supportive peer networks at university and accessing appropriate course advice (Anderson, Cone, Rafferty, & Inoue, 2022; Anderson et al., 2020). As a result, some made inappropriate subject choices leading to failed courses and/or incomplete degrees. Students expressed a strong sense of responsibility for their families’ economic wellbeing, and high levels of personal anxiety when faced with poor educational outcomes.

Our project also sought to foreground refugee-background young people’s voices in relation to secondary-tertiary education transition. Prior to this project, limited research internationally had explored refugee-background students’ navigation of the secondary-tertiary education border, with none in NZ. Most NZ research on refugee resettlement had focused on refugee-background families and communities rather than refugee-background young people themselves (Sampson, Marlowe, de Haan, & Bartley, 2016).

Research intentions

This participatory action research project involved working with refugee-background students to identify and enact practices that promoted their capacity to navigate and negotiate the secondary-tertiary education border. The project explored four questions: (1) How do refugee-background students imagine and experience the secondary-tertiary education transition? (2) What strategies do they employ to navigate this transition successfully? (3) What institutional practices foster students’ ‘navigational capability’ in secondary and tertiary education? (4) How might students’ navigational experiences inform resettlement, and teaching and support practices in secondary and tertiary education institutions? Our project built on previous research, substantively and methodologically — through its longitudinal focus on refugee-background young people’s navigation of the secondary-tertiary education border and its focus on tertiary education broadly (not just university education); and through our use of a participatory, strengths-based approach.

What we set out to do

Our project involved collaborating with refugee-background students in Dunedin and Invercargill as co-researchers across three years, to map, plan, and explore their educational pathways. We also worked with the students to develop resources that might inform pathways support in secondary and tertiary education, and assist refugee-background students and their families – primarily, a documentary film. The project revolved around regular workshops held online and in Dunedin and Invercargill. Data were collected during workshops, interviews, and additional events organised with our participants (see more below).

How we did it

We obtained ethical approval from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee in December 2019 (reference number 19/175), and commenced the project in April 2020. We had planned to recruit participants using a purposeful sampling approach through face-to-face information sessions for refugee-background secondary students in each city who were interested in tertiary study, but our project commenced alongside the beginning of the first six-week ‘lockdown’ due to COVID-19. Therefore, we recruited students through emails sent to Invercargill and Dunedin-based school staff identified by Ministry of Education personnel and project advisors as key contacts for refugee-background students, and through ‘snowballing’, as team members and school staff shared information about the project via their networks, and students shared project information with each other.

Initially, 18 young people joined the project, and this grew to 44 young people by the end of the three years. All were aged 16-21 years; 29 from Dunedin (24 female and five male), and 15 from Invercargill (nine female, and six male). Most joined the project while in senior secondary school, except for two, who joined while engaged in university access programmes, and two, who were neither studying nor working. By the end of 2022, 20 of our participants were in tertiary study. Most Dunedin-based participants spoke Arabic as their first language and came from Syria, with the exception of two who came from Palestine. Of the other Dunedin students, four were from Afghanistan, and spoke Dari/Farsi as their first language, and one was Colombian, spoke Spanish, and had come to Dunedin from a resettlement location other than Invercargill. All Invercargill-based participants were Colombian and spoke Spanish. Most Colombian participants and some Dunedin-based participants had come to NZ via a third (and sometimes, fourth or fifth) country (e.g., Ecuador, Venezuela, Iraq, Lebanon, Cyprus, Turkey and Malaysia). Some Invercargill participants came from families who had experienced intergenerational internal displacement, while the Syrian young people came as an outcome of the recent conflict. Most participants had come to NZ between six months and four years prior to our project commencing, with one exception, who came five years prior.

Over the course of the project, we facilitated 26 workshops, 21 in-depth interviews, and countless informal conversations. Table 1 outlines our data collection approaches alongside each research question.

| Research question | Data sources |

|---|---|

| How do refugee-background students imagine and experience the secondary-tertiary education transition? |

|

| What strategies do they employ to navigate this transition successfully? |

|

| What institutional practices foster students’ ‘navigational capability’ in secondary and tertiary education? |

|

| How might students’ navigational experiences inform resettlement, and teaching and support practices in secondary and tertiary education institutions? |

|

We invited young people to contribute visual data in the form of maps and still photographs, and workshop discussions included multiple peer and group conversations and peer interviews, which were recorded, with participants’ permission. Initially, workshops were designed as both a means for generating data with, and providing access to, education pathways information for the young people. Workshops also offered an opportunity to consult participants on the research team’s analysis and ideas for disseminating research findings.

Our project team roles were as follows. As Principal Investigator, Vivienne oversaw all aspects of the project, including ethical approvals, recruitment, workshop organisation, liaison with schools and resettlement staff, project communication, data handling, data analysis, and dissemination of findings. Jo and Amber supported the Dunedin-based workshops and Dunedin-based students as they moved into tertiary study. Ali and Alejandra provided research and administrative assistance, helping run and organise workshops, maintaining communication with students, managing and coding data, and leading the development of the documentary film. Ali and Alejandra were also our language specialists: Ali is a Farsi/Dari speaker, and Alejandra speaks Spanish. We employed an Arabic language interpreter at the beginning of the project, and (before Alejandra joined the project), Spanish-language interpreters in Invercargill. Anna joined the project in 2022 and assisted with the organisation of our final workshops, film premieres, and ongoing project communication and dissemination. Anna also has Spanish language expertise. Glenda was our main project team member in Invercargill. She helped us broker relationships with students and find interpreters, and supported all workshops involving Invercargill students. Glenda, Jo, Amber, Alejandra, Ali, and Anna contributed to data analysis at team planning days and/or through contributing to writing projects and presentations (which Vivienne led) and the film production process (which Ali led). Pip and Jarrah helped us conceptualise the project initially, provided critical advice throughout, and brokered our relationships with Ministry of Education and NZ Red Cross staff in Dunedin and Invercargill and nationally.

During our first (2020) workshop, we explained the project and invited students to draw a map depicting their education journeys to date and their educational aspirations (see Anderson et al., 2023). We also asked students to identify people or factors that they felt supported their educational journeys, and any things that made their education journeys difficult. Students shared their maps with each other, and we planned subsequent workshops based on students’ aspirations and ideas. From June 2020 until December 2021, we met face to face in Dunedin and Invercargill. Between workshops, we maintained contact with students via a WhatsApp group. Subsequent workshops explored possible tertiary education pathways, career pathways, senior tertiary students’ advice, local tertiary education institution campuses, part-time work opportunities and job-seeking, options for funding tertiary study, application processes, stress and coping, and study skills. In 2022, most of our workshops were weekly afternoon tea sessions with new tertiary students, where we explored with students the everyday challenges and joys of commencing tertiary study. During 2022, all workshops were in Dunedin, although we maintained connection with Invercargill-based participants via zoom and WhatsApp. All workshops involved food and drink. In addition to our regular workshops, in 2020, we held five online Q&A sessions in response to young people’s interests and apparent needs. Workshops and project activities were multilingual, although English became more dominant as participants’ English-language confidence increased.

As part of the project, we created two documentary films – the first, a short (20-minute) film that provided an overview of our first year of project activities, and the second, a full-length (68-minute) documentary film exploring young people’s aspirations, ideas about their lives, and educational journeys. A subset of our participants elected to form a ‘film crew’. From 2020-2022, they contributed to planning, editing, making and subtitling the films.

We concluded 2020 and 2021 with ‘celebration workshops’, where we revised the year’s workshop content, shared work we had created, and invited young people’s input into our analysis, dissemination plans, and project planning. In 2022, we concluded the project with two public premieres of the full-length Transitions Project film – Not Just Dreams – one at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, and one at Centrepoint Theatre, Invercargill. We had ethical approval to share film material in education settings. Following the families’ endorsement at the premieres, we gained ethical approval for film festival release, pending the consent of all involved.

Data analysis was multi-layered. Participants chose what to share with us and each other (Kindon, 2016), and engaged in collaborative analysis and project planning at end-of-year workshops. The research team also analysed data through an iterative, ethnographic process of ‘noticing’ and reflection (Braun, Clarke, & Hayfield, 2019; Kincheloe, 2009). We used NVivo software to generate “summary themes” based on our interview, observational, and visual data, in light of our research questions, literature, and students’ analyses (Braun et al., 2019, p. 5). We then engaged in “reflexive thematic analysis”, applying theory and contextual observations to the summary themes (p. 5). We were interested in recurring patterns and exceptional evidence or cases; and the intersections and contradictions between our data, and refugee resettlement and education policy in NZ (Fine & Weis, 2005). As well as attending to themes in our data, we also generated illustrative case studies or ‘stories’ as a means to capture the complexity of young people lives and experiences in relation to their education pathways over time (Kindon, 2016).

What we found

Research questions 1 and 2: How do refugee-background students imagine and experience the secondary-tertiary education transition, and what strategies do young people employ to navigate this transition successfully?

The young people in our project were profoundly diverse, but all articulated high aspirations of education as a pathway to a better life for themselves and their families. Colombian participants recalled explicit promises about education in NZ. Valentina, Paito, Whitney and Dorothy Jenn[1] described pre-arrival discussions with UNHCR interviewers as resulting in “dreams” (Paito), “illusions” (Whitney), and “fantasies” (Dorothy Jenn) that, “Everything will be better here” (Valentina). Dorothy Jenn recalled a specific promise that she could go to university in NZ:

The man said that when we arrived, we could go straight to the university. I … told him, “but I haven’t finished my studies, and therefore I don’t have the documents” … The man said that you don’t need them; you could go there and study at the university. … They painted that picture for me, and I was ready to go!

Some young people noted that positive expectations were also fuelled by staff at the MRCC, saying, “We were told that … we were going to be able to go to university, that age was not an impediment to study” (Daniel).

In our first (online) workshop, we asked participants to create an education map illustrating their educational aspirations and enablers or hindrances in this regard. Most maps expressed a desire to work in medicine or dentistry. However, young people’s answers revealed limited knowledge of study pathways. For example, one student described radiology as an alternative to medicine, but radiology is a medical sub-specialty. Another named medicine as an alternative to dentistry, without regard for entry criteria. Students’ articulation of possible education and career pathways revealed high aspirations but a limited understanding of the range of pathways possible, and what they involved.

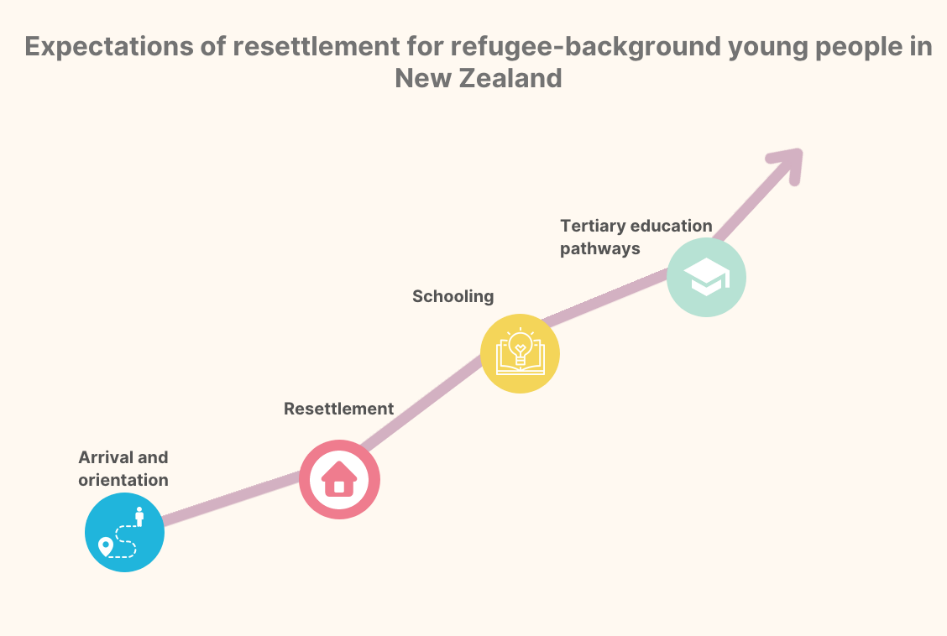

Young people’s maps and conversations represented education as a path to social mobility, in more or less linear terms (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expectations of resettlement for refugee-background young people in NZ

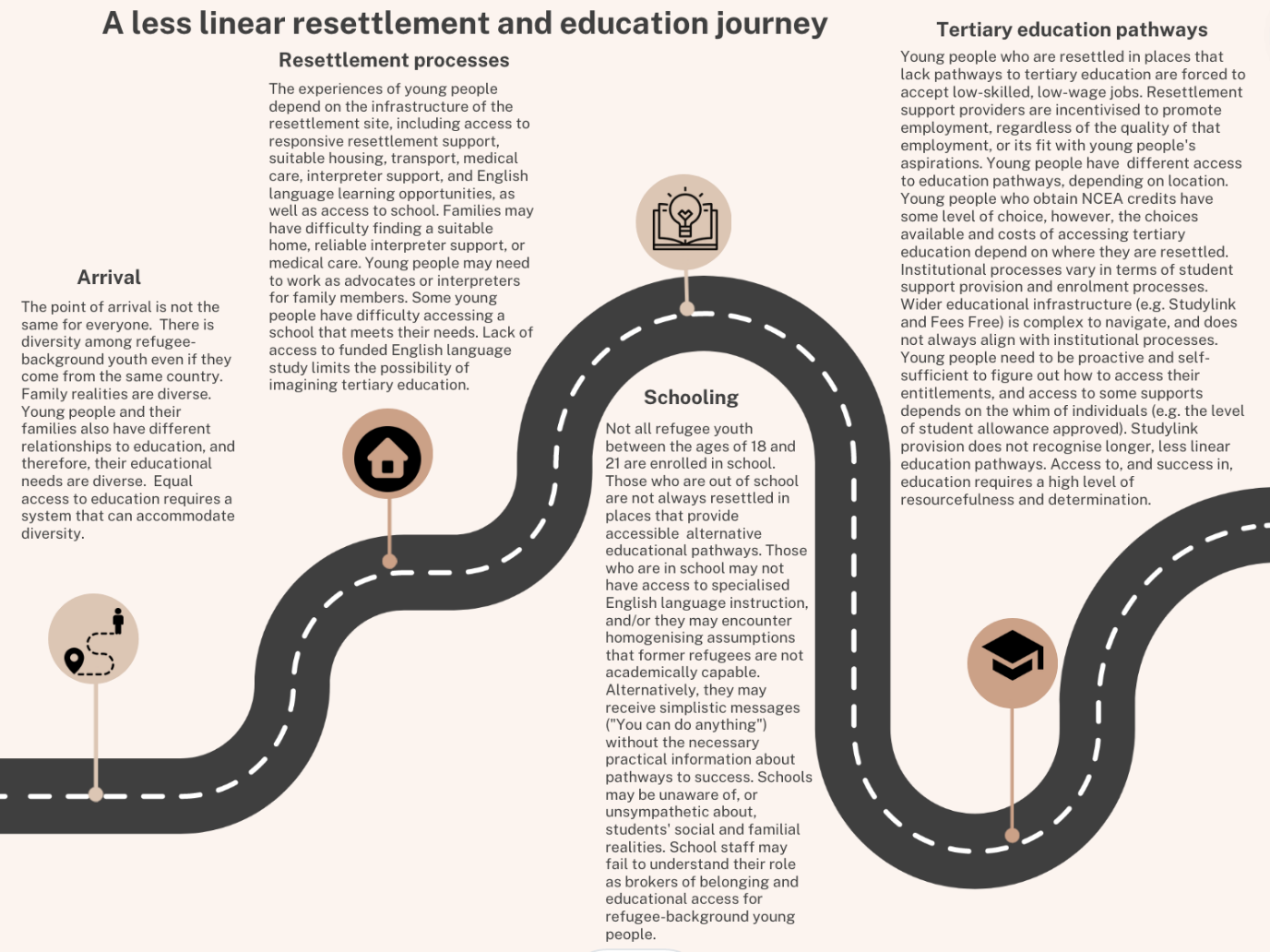

However, in practice, most young people in our study had less linear experiences, and some encountered major structural barriers that made access to education difficult or impossible. Figure 2 provides a more complex picture of young people’s resettlement and education experiences, derived from our data.

Figure 2. A more complex representation of resettlement for refugee-background young people in NZ

In discussing their educational aspirations, young people revealed the active work they engaged in to make sense of their lives and possible futures beyond school. We have described three ways in which they talked about their navigational work: (1) as “resistance”, or actively navigating barriers; (2) as the underground (emotional and psychological) work of holding onto hope and a sense of future; and (3) as a “relational” undertaking – work done in relation to, or with support from, others, or as a means to improve others’ lives (Anderson et al., 2023).

Educational navigation through resistance

Participants in our project referred to language learning as a matter of urgency, and in some cases, decried a lack of specialist English language teaching; however, they resisted teachers’ representation of them as only language learners, or conflation of language learner status and academic capability. Young people drew connections between negative assumptions about them as language learners and a broader sense of (un)belonging at school, pointing to the need for proactive work to ensure a more affirming environment for English language learners in monolingual school settings. Luna described having difficulty making friends: “It’s like they don’t want to waste time with a person who can’t understand everything they say”. Valentina said, “I don’t have friends at school … When I arrived, I tried to use my English … it was like it didn’t work”. Valentina suggested the need for “inclusion activities or something that helped them to understand that we do not speak the language, that … they have to have patience with us”.

Dorothy Jenn expressed outrage at the actions of a drama teacher, who positioned her as an outsider who was not capable of participating in classroom activities due to her status as a language learner. She described her class as follows:

The teacher told everyone, ‘She doesn’t have much English. She doesn’t understand very well’. So, every time I had drama class, the teacher would wave to me, and I knew I had to go and sit in the corner of the room … The teacher treated me as if I had some kind of disability.

Dorothy Jenn recalled how classmates tried unsuccessfully to counter the teacher’s exclusionary behaviour: “The girls … said, ‘Let’s include her in the group’”. However, she explained that “the teacher intervened and said, ‘No, not her. She doesn’t know English. She is … not going to be able to do anything’”. Similarly, Amina and Sogand resisted teachers’ apparent view of them as only English language learners. Here is an excerpt from a workshop conversation:

Amina: Usually in school for us, like Syrian or mostly refugees, when you go and ask teachers about like topics like this (education pathways), the main thing they just said is like, ‘Don’t worry about this kind of stuff; focus on your English first’, which is annoying …

Sogand: My God, yes, they always say that … they always say it.

Amina: So they don’t give you like what you need to do or they don’t explain to you what should you know and what you shouldn’t. They just tell like ‘focus on your English first’, but . . . if you focus on your English but you don’t know what to do, like what’s so important with your English? . . . So . . . sometimes I will ask other students . . . I ask them a lot and then I Google, I go to websites . . . The school never mention [extra-curricular science programme] but then once I knew about it . . . I went to apply; the teacher was so surprised, like ‘why do you want to apply for this?’. So school doesn’t really help like second language students to focus on this kind of stuff ’cause first they focus on their language (Anderson et al., 2023, pp. 260-261).

Amina resisted the conflation of English language learner status and academic capability and the related assumption that all refugee-background students are the same (not interested in extra-curricular opportunities). She reflected, “They’re trying to . . . work with everyone at the same level, like ‘learn English first’, but some students, they have already learnt English and they’re good enough just to learn about this [other] kind of stuff” (Anderson et al., 2023, p. 261).

Participants also expressed (and described) resistance to peer discrimination and bullying. Luisa and her parents described a series of incidents involving Luisa, another Colombian student, and Luisa’s sister. Luisa began:

I was with a girl who spoke Spanish … And the [other] girls here didn’t like it. They even wanted to bully us for speaking Spanish … During the breaks, we were pushed. But we never responded … Because that was what they wanted … We said among ourselves, ‘They are all kiwis; if we react to their provocations, things are worse for us’. One day we were in class, and the teacher leave the classroom for some minutes … We were … talking in Spanish … and the girls who were behind us shouted, ‘Shut up!’ … So, we kept talking slowly and they told us, ‘Fuck you Colombians’ (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala et al., 2023, p. 7).

Luisa told us that, despite telling the teacher, nothing changed; the students “continue[d] behaving in the same way”. Following a vandalism incident, her parents “talk[ed] to the teachers”. Teachers countered Luisa and her family’s resistance, saying, “It [is] normal” because they are “just girls”. Similarly, Daniel described his and Dorothy Jenn’s resistance to peer discrimination involving their brothers. Daniel noted that this would not have been necessary in Colombia, where “teachers are like our second parents”. He suggested that, in NZ, “there are no firm, credible calls to correct misbehaviour”.

One 17-year-old student resisted a school’s refusal to let him enrol, and their failure to be upfront about their reasons for this. Cameron, whose gender expression challenged masculine norms, noted that the school’s response to him differed to the responses received by his straight, cisgender refugee-background friends. When Cameron asked directly why he was not allowed to enrol in school, school staff gave evasive responses: “They told me because of my level of English, and the teachers looked at each other … I insisted and said to them, ‘But why?’’. Cameron suggested that it would be less humiliating for young people if schools were upfront about their exclusionary practices: “We need a source that provides reliable information, and that tells you from the beginning: ‘Yes, in this school if they are going to receive you’ or ‘in this school, it is very difficult for them to receive you’”. Cameron said, “I would not like another boy of my same gender or my same community to experience the same thing … You feel humiliated”.

Educational navigation as underground and relational work

While young people revealed the creativity and persistence involved in navigating education, they also alluded to the psychological and emotional labour that this entailed, in some cases, due to the impacts of trauma. Laila (a Dunedin student) described the loss of close friends (in Syria) as impacting her sense of motivation, noting that “self-doubt”, “overthinking” and “anxiety” were, for her, barriers to success (Anderson et al., 2023, p. 265). Daniel, whose family suffered severe hardship in Colombia and Ecuador prior to arrival in NZ, linked self-doubt with past experiences of loss and deprivation, saying:

We feel that this place is not for us, or we do not deserve to be there because sometimes we have so many things in our hands, such as having a computer or knowing that we have new opportunities. However, we do not know that we have them because we are not used to having opportunities. We are not used to knowing that we have several alternatives to get ahead.

Luna (from Invercargill) expressed the sense of weight associated with having opportunity following extreme hardship: “I am worried about not being capable of achieving my goals. I am worried about being worried. I am worried of letting myself down”.

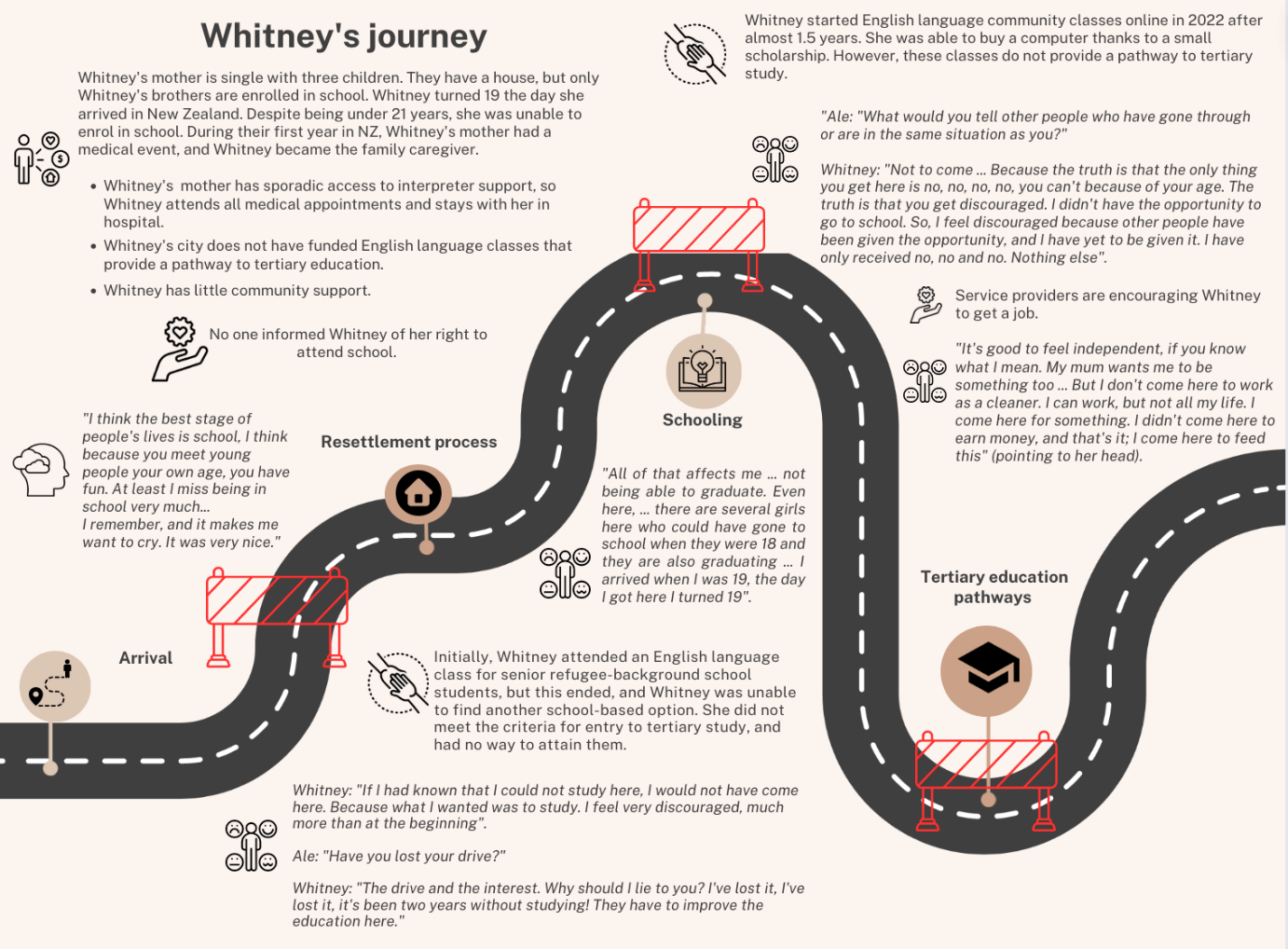

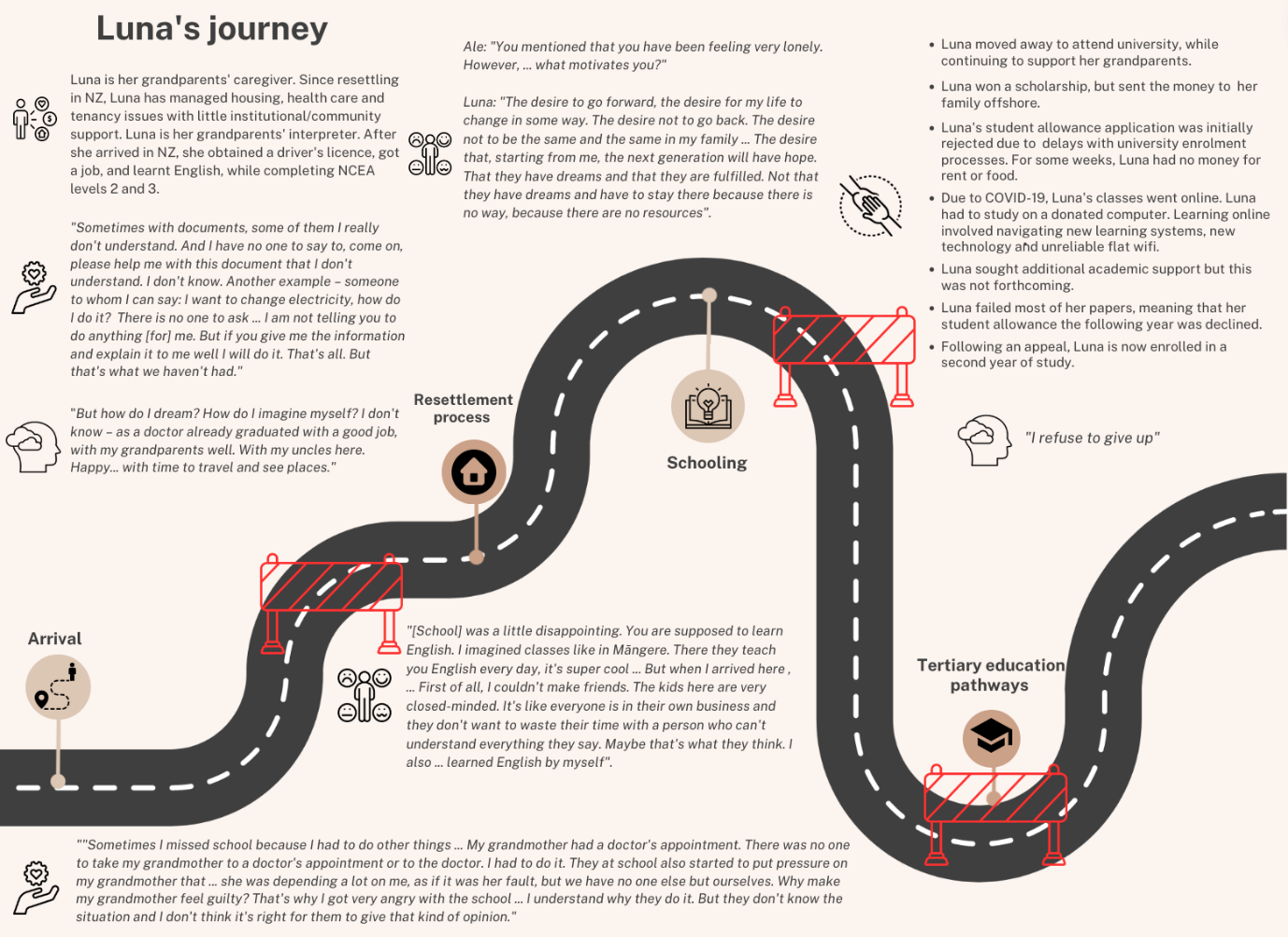

Below, we highlight two cases in depth to illustrate the complex ways that structural and personal factors necessitated difficult underground work for young people seeking an education. Figure 3 describes Whitney’s education and resettlement journey, and Figure 4, Luna’s. In some respects these two young people were exceptional cases – both were caregivers to family members with complex health needs who had received patchy resettlement support. Both were resettled in Invercargill, which impacted their access to a range of social services, including tertiary education options. While the cases were exceptional for the structural complexity encountered that impacted on young people’s educational navigation, they were also representative in some respects. Many of the young people in our project described acting as interpreters, translators and advocates for parents, siblings and family members. We have spoken to other young people with similar stories from other regional centres. These cases highlight the degree to which factors can compound for young people, making educational navigation profoundly difficult or impossible. In the figures below, we seek to capture some of the structural barriers that shaped Whitney and Luna’s access to education, the help sources they identified as present or absent, and how they made sense of their educational journeys.

Figure 3. Whitney’s resettlement and education journey.

Whitney (Figure 3) arrived in NZ at 19 years, and initially attended an English programme hosted by a local school. However, once this ended, she was unable to enrol in mainstream classes. Whitney was unaware of her legal entitlement to remain at school until the age of 21. Following her mother’s illness, Whitney became a full-time caregiver, making day-time classes impossible. Based on her experiences, Whitney represented resettlement in terms of “harm”: “If they see a 19-year-old or an 18-year-old coming, the best thing to do is to tell them that this city doesn’t suit you … we will harm you” (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala & Mostolizadeh, 2023. Whitney noted that service providers that interacted with her and her mother were encouraging her to find employment. She acknowledged the value of (economic) independence, but stressed that being a cleaner was not her aspiration.

Luna (Figure 4) gained NCEA levels 2 and 3 while learning English and supporting her grandparents. Based on this achievement, she was accepted into a university access programme, which required her to move cities. At the start of Luna’s programme she had difficulty with university admission processes. As a result, her student allowance application was declined, leaving Luna unable to buy food. From the start of the year, teaching moved online due to COVID-19. Luna obtained a donation laptop and tried to learn online from home, but poor wifi, and unfamiliarity with both the online platform and content-related gaps made this difficult. When Luna sought additional support, programme staff were unhelpful, and Luna could not find another source of academic support while learning from her flat. Simultaneously, Luna sought to support her grandparents from a distance. Luna failed more than half of her papers, so her second year student allowance application was declined. However, Luna sought an appeal and she is now enrolled in another year of university study while continuing to support her grandparents. Luna has now connected with a support service for students from low-income schools, and says, “I refuse to give up!”.

Figure 4. Luna’s resettlement and education journey.

Whitney and Luna exemplify the profoundly complex navigational work required of refugee-background young people when resettlement, education and other social services do not serve them or their families well. Both young people were resettled in a city with limited tertiary education pathways options, and their families received patchy resettlement support. A failure of advocacy and support across the education sector necessitated Luna’s insistent determination to remain at university. While Whitney maintained a desire for further education, and determinedly sought out opportunities, she saw meaningful education pathways as increasingly out of reach.

Both Whitney and Luna’s journeys also highlighted the relational work of educational navigation. Factors shaping their family circumstances impacted their options moving forward. Woven throughout their case descriptions are glimmers of advocacy/support (e.g., in obtaining a computer or reinstating a student allowance), but also the lack thereof (e.g., requiring them to act as interpreters at family members’ medical appointments). The relationality inherent in navigational work is also evident in our answer to the third research question below.

Research question 3: What institutional practices foster students’ ‘navigational capability’ in secondary and tertiary education?

Inclusive, responsive and affirming teaching practice and learning environments

Our participants identified teachers and school staff as critical enablers in relation to educational access and success. They also linked a sense of inclusion in school with a broader sense of inclusion or belonging in NZ (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala, & Mostolizadeh, 2023). As noted earlier, young people in our study were critical of school practices that positioned them only as language learners, and their reflections on enabling teachers focused on much more than language teaching. Luisa (an Invercargill student) recalled an inclusive, responsive mathematics teacher who adapted his teaching in consultation with refugee-background students in his class. She described his work as follows:

He explained to the whole class first and then he took his time and sat next to us to explain to us and we understood … We could do signs, or we used the translator, and he understood and told us how to say things better. He … knew that we felt embarrassed to ask in front of the other girls. Then when we raised our hand, he approached us, sat with us and spoke to us slowly … He even asked us: how do we understand better … writing or talking? Then, we told him … please write the explanation down for us, he wrote and explained to us step by step, and we understood him. (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala, & Mostolizadeh, 2023, pp. 8-9)

Luisa’s teacher invited and answered students’ questions in ways that avoided embarrassment, and communicated in ways that supported students’ mathematical understanding and confidence as English language learners. The teacher’s queries about what would best help Luisa and her peers learn positioned them as experts in relation to their own learning. He was responsive and open to change – altering his teaching in response to their preferences. Luisa described this teacher as allowing her to feel very comfortable in mathematics.

Sogand (a Dunedin student) recalled a secondary outdoor education class where she felt at “home” and where she overcame her sense of outsideness and dislike of “white people”. She recalled: “For the first time in my life, I thought that if I ever had a problem, and I needed to tell a friend, that class was my safe space … Everyone treated each other, like, family”. While Sogand did not explicitly mention the class teacher, she pointed to their careful creation of peer-based, memorable activities that fostered a sense of cohort over time:

Through that class … the wall was broken down, so we got to know both sides. And that made it really easy to connect, to meet the true person… That class [was] the diversity that you never expect in your life … it was a really special place.

Sogand was more explicit about a careers teacher, who she credited with enabling her to begin tertiary study. Here she recalls a specific interaction that was pivotal in supporting her subsequent decision-making:

The greatest interaction that I had with the staff was my school’s career advisor – she made me feel like I was some special person on this earth…I am the owner of this life…And I was the one who should decide what’s good for me and what’s not…Her words were like a comforting pillow and a blanket…it was like my Grandma’s arms…holding me…She was what triggered the whole motivation and the life that I have chosen to go through…she just helped me get out of the bad state that I was in. (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala, & Mostolizadeh, 2023, p. 9)

Sogand described this teacher as fostering a sense of agency, safety, and future. Other students described support staff who affirmed their communicative competence, and careers teachers who alerted them to educational scholarships and other opportunities, and supported them to apply.

Enabling peer relationships, and relationships with trusted community members

Participants identified people other than school staff who enabled their access to education. These included supportive family members, “role models” (e.g., older friends and siblings), and classmates, in particular, Māori and Pacific students who acted as allies. Earlier, we discussed how classmates intervened when Dorothy Jenn was excluded by her teacher from classroom activities. Luisa described a sense of solidarity with Māori and Pacific students who helped her in school and counteracted negative classroom interactions. Salomé described a group of Māori friends who came to her house and supported her language learning (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala & Mostolizadeh, 2023, p. 8):

At school, … I don’t interact much with the other Kiwi girls … But the Māori are the ones who have always helped me; they helped me a lot! …Or the girls that come from other places like Samoa. They are the ones who realise that I’m not understanding, and they come up to me and ask me, “You need help?”. And they explain things to me. But the other girls don’t. (Luisa)

At school I felt good. I liked it. Because [I] made friends… some girls who are very good … They are Kiwis – Māori … I have like five friends … Sometimes they come to the house … One of them, when I don’t pronounce the word as it is, they tell me, “No, Salomé, say it like that”, and they repeat it to me. (Salomé)

Participants also described trusted community members whose support they found enabling, including local Ministry of Education staff (“she fought for us”), resettlement support volunteers who provided information, mental health workers who provided professional support, and individual government agency staff who were known as trusted sources of navigational assistance.

Daniel suggested that exclusionary school interactions increased his sense of not belonging in NZ, saying, “What leads us to think like this is that there is no such welcome” (Anderson, Ortiz-Ayala, & Mostolizadeh, 2023, p. 8). By implication, inclusionary practices and inclusive teachers can be seen as brokering a broader sense of belonging, in NZ’s education system and in NZ more broadly.

Access to necessary social services, education pathways, and practical information

This final answer to research question 3 is derived from our data by implication. Whitney and Luna’s journeys (above) demonstrate the impact of weak social service provision and limited education pathway options. By the conclusion of our project, educational outcomes were tracking very differently for these two students, but our project had enabled some level of access to education for both of them (in Whitney’s case, through communicative English language classes and support applying for a small scholarship, and in Luna’s, through support accessing course-related information and a student allowance). While social support structures for resettled refugees remain weak, geographically uneven, or disconnected – trusted advocates, mentors, role models and advisers can play an crucial role in enabling young people’s educational access and success.

What we think needs to happen next

Research question 4: How might students’ navigational experiences inform resettlement, and teaching and support practices in secondary and tertiary education institutions (and beyond them)?

Government

- Formally recognise refugee-background young people as priority learners at all levels of education.

Currently, refugee-background young people are invisible in NZ’s education system. This leaves much to chance. Across two cities and limited educational institutions we saw widely varying education provision and support practices. Formal recognition of refugee-background students as priority learners would ensure that funding and accountability mechanisms drive enabling institutional practices for refugee-background young people across all geographical centres.

- Ensure that refugee resettlement policy privileges participation and belonging.

Currently, refugee resettlement policy and practice prioritises economic independence. In our study, this was apparent in the lack of support some students received to remain engaged in education and the concurrent encouragement to find paid employment, regardless of whether or not it aligned with their aspirations. If education is an enabling right (Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action, 2015), supporting access to education and the creation of accessible education pathways should be a priority in the resettlement process. Equitable access to education also necessitates equitable access to resettlement support, funded specialist English language teaching (if needed), health care, and housing (among other social services).

- Ensure that, at all levels, the education system is structured around a commitment to keeping “learners at the centre” and creating “barrier free access” (https://assets.education.govt.nz/public/Documents/NELP-TES-documents/NELP-TES-summary-page.pdf).

Currently, some aspects of our education and resettlement systems have the opposite effect. ESOL funding is limited, and roll-based funding models do not serve schools well where young people’s attendance is patchy due to family circumstances. At tertiary level, Studylink processes are decoupled from institutional processes, creating complexities for young people and challenges navigating both. Study support provision (available through Studylink) fails to allow for longer, less linear pathways. While workarounds (e.g. Studylink appeals) are possible, these require that young people have the confidence to question systemic practices and approach institutional staff for support. Many young people in our study required support and advocacy to access basic educational entitlements, but targeted support is not available for refugee-background students in all tertiary institutions. Barrier-free access with learners at the centre necessitates accessible entry processes and study pathway options for young people no matter where they are resettled and regardless of their educational background; allowing for flexibility, non-linearity, and growth over time.

Kaiako, resettlement support staff, and educational institutions

- Know that your work matters – a lot

While geography, uneven tertiary education provision, and multiple other social factors create educational (and social) inequity, individual school staff play a critical role as educational enablers. Effective teachers facilitate young people’s access to curriculum/subject knowledge and learning-related skills. Effective teachers also support young people’s access to peer networks and practical information in ways that compensate for weak resettlement structures. Our study showed that teachers and school leaders are important role models, and brokers of belonging. Their affirmation of refugee-background young people (and their families), practical guidance and support, successful promotion of positive peer interactions, and willingness to intervene when negative interactions occur, affirm young people’s right to an education, safety, and sense of belonging and future.

Below are a list of questions (derived from our data) for teachers and school leaders that may serve as a useful basis for reflection and practice:

- Are my interactions with students affirming, mana-enhancing, and agency promoting?

- Do my actions and teaching approaches foster empathy towards newcomers and minoritised students?

- How do my classes ‘feel’ to these students?

- How might I foster the development of friendships through my teaching?

- Do I invite all students to share their aspirations, and do I take these seriously?

- How well do I support students’ understanding of possible pathways towards their aspirations, and help them map their ‘next steps’?

- How well do I support all students’ right to learn?

- Do I show a commitment to all students’ learning?

- How multi-lingually competent am I? How well do I understand language learning processes and support language learning?

- Do I take student safety seriously? How effectively do I communicate this?

- Do my communications and everyday actions foster the trust of students and whānau?

- Do I recognise my role as an advocate for the young people in my classroom, and for former refugees, as a representative of the State?

- Help refugee-background young people understand and navigate possible pathways

Refugee-background young people need access to practical information about education and career pathways in their new resettlement context. Where young people’s aspirations do not align with their educational backgrounds, they need information about alternative pathways, alternative career options, and less linear routes. In our study, careers teachers played an important role in supporting young people’s understanding of possible pathways, but by taking young people’s aspirations seriously (or not), classroom teachers were also pathways enablers (or obstructors). It is critical that school staff recognise refugee-background young people as more than (English) language learners, and take seriously teachers’ role in supporting young people’s access to pathways information, mentoring, and rich (career-enabling) experiences. Since pathways are not static, but unfolding, and many young people change their ideas over time, pathways mentoring is also needed. Our project provided this for a group of young people in two locations, and in this regard, mitigated a lack of navigational support at institutional level for some of the young people we encountered. Ideally, tertiary education institutions should employ dedicated support staff who can be trusted advisers to refugee-background young people as they learn about what they enjoy and the areas where they are successful. In the absence of more joined up resettlement and educational support, we also suggest the possible value of regional ‘education navigators’ who can provide trusted pathways advice across secondary and tertiary institutions, based on young people’s unfolding education journeys.

Project team

Associate Professor Vivienne Anderson is Dean of Te Kura Ākau Taitoka—The University of Otago College of Education. Vivienne’s research explores questions relating to educational equity and access, education pathways, and the policy–practice interface. Email: vivienne.anderson@otago.ac.nz

Dr Alejandra Ortiz-Ayala is a Lecturer and Postdoctoral Researcher at the Willy Brandt School of Public Policy, University of Erfurt, Germany, and former Assistant Research Fellow at the University of Otago College of Education. Alejandra’s research explores how state actors, social policies and everyday practices foster and disrupt social cohesion.

Sayedali Mostolizadeh (Ali) is a documentary film-maker and PhD student in the Department of Sociology and Legal Studies at the University of Waterloo, Canada, and former Assistant Research Fellow at the University of Otago College of Education. Ali’s research foregrounds the voices of displaced and detained people through the medium of documentary film.

Anna Burgin is a PhD student in Peace and Conflict Studies and Education at the University of Otago and an Assistant Research Fellow at the University of Otago College of Education. Her research explores everyday peace-making and volunteering in refugee resettlement contexts.

Dr Jo Oranje is an applied linguist and Professional Practice Fellow in the Division of Health Sciences at the University of Otago. Jo provides academic support for refugee-background students studying health science subjects.

Amber Fraser-Smith is an ESOL lecturer at Otago Polytechnic Te Pūkenga, where she teaches refugee- background students. Amber’s master’s research explored questions relating to refugee education.

Pip Laufiso is Senior Adviser Priority Learners at the Dunedin office of Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga–the Ministry of Education.

Jarrah Cooke is an Occupational Therapist and the Pathways to Employment National Operation Lead for NZ Red Cross, based in Dunedin.

Glenda Atkins is Special Educational Needs Coordinator and an ESOL teacher at Aurora College, Invercargill.

Footnote

- All participant names in this report are pseudonyms. ↑

Publications and Presentations

McLaughlin, T., Cherrington, S., McLachlan, C., Aspden, K., & Hunt, L. (2020). Building a data culture to enhance quality teaching and learning. Early Childhood Folio, 24, 3-8. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0080

McLaughlin, T., Cherrington, S., McLachlan, C., Aspden, K. & Hunt, L., (2021, November). Using data to explore insights to sustained shared thinking to deepen young children’s learning. Paper presented at the NZARE Conference, Wellington, New Zealand. Available at: https://eyrl.nz/presentations/

McLaughlin, T., Cherrington, S., McLachlan, C., Aspden, K. & Hunt, L., (2021, July). Sustained shared thinking and other learning focused teacher-child interactions: Emerging insights from

research. Paper presented at the PECERA Annual Conference, Wellington, New Zealand. Available at: https://eyrl.nz/presentations/

Cherrington, S., McLaughlin, T., Aspden, K., Hunt, L., & McLachlan, C. (2022). Data, knowledge, action: The use of data systems as auxiliary tools to aid teachers’ thinking about children’s

curriculum experiences and teacher practices. In C. McLachlan et al (Eds.) Assessment and data systems in early childhood settings: Theory and practice (pp. 287-308). Singapore. Springer.

Aspden, K., Hunt, L., McLaughlin, T., & Cherrington, S. (2022). Developing teacher-researchers’ capacity to support the use of new data systems. In C. McLachlan et al (Eds.) Assessment and data

systems in early childhood settings: Theory and practice (pp. 309-330). Singapore. Springer.

McLaughlin, T., Cherrington, S., Hunt, L., Gifkins, V., Aspden, K., McLachlan, C., Linton Kindergarten., and Makino Kindergarten. (2022). A data-informed look at how sustained shared thinking can

promote child learning and progress, Early Education, 68, 45–52. https://eej.ac.nz/index.php/EEJ/article/view/69

References

Anderson, V., Cone, T., Rafferty, R., & Inoue, N. (2022). Mobile agency and relational webs in women’s narratives of international study. Higher Education, 83(4), 911-927. doi:10.1007/s10734-021-00714-7

Anderson, V., Mostolizadeh, S., Oranje, J., Fraser-Smith, A., & Crampton, E. (2023). Navigating the secondary-tertiary education border: refugee-background students in Southern Aotearoa New Zealand. Research Papers in Education, 38(2), 250-275. doi:10.1080/02671522.2021.1961300

Anderson, V., Ortiz-Ayala, A. & Mostolizadeh, S. (2023). Schools and teachers as brokers of belonging for refugee-background young people. International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2023.2210591

Anderson, V., Ortiz-Ayala, A. & Mostolizadeh, S. (In press). Refugee-background students in southern New Zealand: Educational navigation and necessary self-sufficiency. In Pinson, H., Bunar, N. and. Devine, D. (Eds.), Research Handbook on migration and education – International perspectives. Edward Elgar.

Anderson, V. R., Cone, T., Inoue, N., & Rafferty, R. (2020). Narratives of navigation: Refugee-background women’s higher education journeys in Bangladesh and New Zealand. Sites: a journal of social anthropology and cultural studies, 17(1), 15-39. doi:10.11157/sites-id458

Baker, S., Ramsay, G., Irwin, E., & Miles, L. (2018). ‘Hot’, ‘cold’ and ‘warm’ supports: Towards theorising where refugee students go for assistance at university. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(1), 1-16. doi:10.1080/13562517.2017.1332028

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Hayfield, N. (2019). ‘A starting point for your journey, not a map’: Nikki Hayfield in conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1-22. doi:10.1080/14780887.2019.1670765

Dryden-Peterson, S., & Giles, W. (2010). Introduction: Higher education for refugees. Refuge, 27(2), 3-10. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.34717

Fine, M., & Weis, L. (2005). Compositional studies, in two parts: Critical theorizing and analysis on social (in)justice. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (third edition) (pp. 65-84). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc.

Hynie, M. (2018). Refugee Integration: Research and Policy. Peace & Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(3), 265-276. doi:10.1037/pac0000326

Immigration New Zealand. (2012). Refugee settlement: New Zealand resettlement strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. Retrieved 27 July 2020 from https://www.immigration.govt.nz/documents/refugees/refugeeresettlementstrategy.pdf

Immigration New Zealand. (n.d.-a). The NZ Migrant Settlement Integration Strategy and NZ Refugee Resettlement Strategy Refresh Project. Retrieved from https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/what-we-do/our-strategies-and-projects/refugee-resettlement-strategy/the-nz-migrant-settlement-integration-strategy-and-nz-refugee-resettlement-strategy-refresh-project

Immigration New Zealand. (n.d.-b). Te Āhuru Mōwai o Aotearoa – Mangere Refugee Resettlement Centre. Retrieved from https://www.immigration.govt.nz/about-us/what-we-do/our-strategies-and-projects/refugee-resettlement-strategy/rebuilding-the-mangere-refugee-resettlement-centre

Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action. (2015). Education 2030 Incheon Declaration and framework for action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning for all. Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 21 September 2020 from https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/.

Kincheloe, J. L. (2009). Critical complexity and participatory action research: Decolonizing “democratic” knowledge production. In D. Kapoor & S. Jordan (Eds.), Education, participatory action research, and social change: International perspectives (pp. 107-121). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kindon, S. (2016). Empowering approaches: Participatory action research. In I. Hay (Ed.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (fourth edition) (pp. 350-370). Ontario: Oxford University Press.

Lenette, C. (2016). University students from refugee backgrounds: Why should we care? Higher Education Research & Development, 35(6), 1311-1315. doi:10.1080/07294360.2016.1190524

Mahony, C., Marlowe, J., Humpage, L., & Baird, N. (2017). Aspirational yet precarious: Compliance of New Zealand refugee settlement policy with international human rights obligations. International Journal of Migration and Border Studies, 3(1), 5-23. doi:10.1504/ijmbs.2017.081176

Marlowe, J. (2021). A fair go for refugees. Expert commentary. Te Tapeke: Fair futures in Aotearoa.: Royal Society Te Apārangi.

New Zealand Immigration. (2022). Claiming refugee and protection status in New Zealand: Ministry of Business, Immigration and Employment.

O’Rourke, D. (2011). Closing pathways: Refugee-background students and tertiary education. Kotuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 6(1-2), 26-36. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2011.617759

Rafferty, R. (2020). Rights, resources, and relationships: A “Three Rs” framework for enhancing the educational resilience of refugee background youth. In V. Anderson & H. Johnson (Eds.), Migration, education and translation: Cross-disciplinary perspectives on human mobility and cultural encounters in education settings, 1st edition (pp. 186-198). Abingdon: Routledge.

Rafferty, R., Burgin, A., & Anderson, V. (2020). Do we really offer refuge? Using Galtung’s concept of structural violence to interrogate refugee resettlement support in Aotearoa New Zealand. Sites: a journal of social anthropology and cultural studies, 17(1), 115-139. doi:10.11157/sites-id455

Ramsay, G., & Baker, S. (2019). Higher education and students from refugee backgrounds: A meta-scoping study. Refugee Survey Quarterly, 38(1), 55-82. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdy018

Sampson, J., Marlowe, J., de Haan, I., & Bartley, A. (2016). Resettlement journeys: A pathway to success? An analysis of the experiences of young people from refugee backgrounds in Aotearoa New Zealand’s education system. New Zealand Sociology, 31(1), 31-48.

Sutton, D., Kearney, A., & Ashton, K. (2021). Improving educational inclusion for refugee-background learners through appreciation of diversity. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1-18. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1867377

UNESCO. (2017). Protecting the right to education for refugees. Retrieved from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000251076

UNHCR. (2010). Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR Communications and Public Information Service.

UNHCR. (2016). Missing out: Refugee education in crisis. Geneva: UNHCR. Retrieved 27 July 2020 from https://www.unhcr.org/57d9d01d0

UNHCR. (n.d.). Refugee data finder. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

UNHCR. (2022). All inclusive: The campaign for refugee education. Geneva: UNHCR.

Wilkinson, J. (2018). Navigating the terrain of higher education. In L. Naidoo, J. Wilkinson, M. Adoniou, & K. Langat (Eds.), Refugee background students transitioning into higher education: Navigating complex spaces (pp. 89-110). Singapore: Springer.

Wilkinson, S. D., & Penney, D. (2021). Setting policy and student agency in physical education: Students as policy actors. Sport Education and Society, 26(3), 267-280. doi:10.1080/13573322.2020.1722625