Introduction

Pacific parents and community members have much to contribute to teacher learning and thus to the education of Pacific students. Although the concept of Pacific success, through the education of Pacific students, has become ubiquitous as an aspiration, there has so far been limited research that has conceptualised Pacific education success in community terms. This is especially true in relation to teacher learning, teacher theorising, and changed practice. Understanding how to socialise teachers to generate and sustain new practice possibilities, informed by appreciation of the values, aspirations, and critiques of the Pacific parents and students they seek to serve, is therefore a priority.

Learning From Each Other is a Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) that provides a relationship-derived description of helpful tools that are useful for communities, educational professionals, and professional development providers to support sustained positive change for Pacific students. Helpful tools are those that make a difference on the ground; provide conceptual and experiential learning that resonates with the ideas and aspirations of Pacific communities; and supports educators, primarily teachers, through developing deep ways of engaging with resources available such as Tapasā (Ministry of Education, 2018) and the Pacific Education Action Plan (Ministry of Education, 2020). The research pairs community consultation with teacher learning, and teacher learning with changed classroom practice, acknowledging the various cultural, experiential, and pedagogic expertise of all participants.

The research process centred two phases of dialogue—dialogue among Pacific communities through fono, and among teachers in professional learning and development (PLD) sessions. The researchers mediated these dialogues. Two research sites were involved, one each in Te Wai Pounamu | South Island and Te Ika a Māui | North Island. One was a faith-based Kāhui Ako (KA), the other a KA founded on a common location. The KA were identified and invited through existing relationships with the researchers. In one case, this involved links with local Pacific communities; in the other, professional relationships based on previous PLD engagement. In this interactive and fluid research, groups of teachers took different paths, particularly in the second year of the initiative, drawing attention to the value of negotiated, responsive research to meet community and teachers’ needs on the ground. It is a testament to all involved that the research continued throughout the COVID-interrupted years 2021/22, albeit in forms changed from the original proposal.

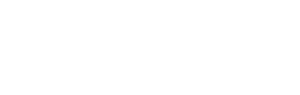

The research questions focus on the effects of access to Pacific voice and Pacific origin concepts on teachers; resultant practice changes; the impacts of change; and researcher learning about the processes involved. The findings show the productivity of a PLD model that brings together motivated teachers, a talanoa approach to safe space for dialogue, the voices of Pacific communities corroborated and clarified by research, sufficient opportunities to learn, and a growth mindset that values learning as a way of improving the self—individual, social, and professional.

FIGURE 1: Learning From Each Other framework

Adapted from Chu-Fuluifaga and Reynolds (2023a)

Relational methodology

The title Learning From Each Other strikes a relational chord. Pacific literature highlights the self as social or relational (Airini et al., 2010; Mila-Schaaf, 2006; Vaai & Nabobo-Baba, 2017). We are all defined by relationships that connect us and make us who we are as members of collectives.

Pacific communities

Over time, the Ministry of Education (the Ministry) has varied in its use of “Pacific”/“Pasifika” in the context of the education of those from Pacific Islands backgrounds who study in Aotearoa New Zealand. Here we follow the current Ministry terminology of Pacific. In this context, “Pacific” is an umbrella term for diverse communities. Diversity includes ethnicity, gender, birthplace, age, generation of migration, and socioeconomic status. “Pacific education” may be helpful to administrators or as an heuristic for schools (and researchers) but can also silence diversity (Naepi et al., 2017; Samu, 2006) within and between Pacific communities. Here we use the term circumspectly, relying on localisation of research as way of sensitising all involved to local Pacific communities and the significance of relationships between people.

Catalytic research

Catalytic research (Baines, 2007; Lather, 1986) is research that seeks to go beyond learning about a context. This kind of research aims to enable those involved as research partners and participants to grow through their involvement and come to higher states of self-realisation and agency awareness. Our relational approach to this endeavour involves catalytic learning that comes from changing situations and, as a result, privileges attention to processes of educational change. We pursue the goal of enhanced relationships between Pacific communities and educators to this end. It is a moral obligation to align the education of Pacific students more closely with Pacific parental aspirations and understandings and to support communities to grow in influence in educational spaces.

Va/vā

We understand relationality through the Pacific origin concept of va or vā. Va has been rendered in English as relational space (Havea et al., 2020; Henry & Aporosa, 2021). Va spaces involve entwined physical, social, and sacred dimensions (Sauni, 2011; Tuagalu, 2023). From this perspective, changing Pacific education involves attending to the relational spaces between teachers who are largely of European cultural background (Education Counts, 2021) and the Pacific communities, families, and students they serve.

The ethics of the va are indicated by the Tongan reference tauhi vā (Ka’ili, 2005; Koloto, 2017) and the Samoan, teu le va (Airini et al., 2010; Anae, 2016). Teu le va has been rendered in English as keeping relational spaces tidy (Anae, 2010), well-configured (Mila-Schaaf & Hudson, 2009), and nurtured (Airini et al., 2010). The research aims to teu le va in Pacific education by facilitating and investigating the support necessary for teachers to achieve the ultimate research aim—enhanced education for Pacific students, facilitated and guided by the voices of Pacific parents.

Talanoa

Learning From Each Other is dialogic research informed by talanoa, a form of conversational interaction that pays attention to the ethics of the va. Vaioleti (2013) describes research talanoa as an oral form that moderates power relations. This includes the power relationships between schools and Pacific homes in Pacific education. Talanoa also involves the empathetic alignment of the emotional and spiritual states of researchers and participants in a space made safe for all through the equalising effect of the dialogic process (Farrelly & Nabobo-Baba, 2014). In this research, we use talanoa to denote our overall dialogic approach to shaping and conducting research with the authentic catalytic purpose of enhancing relationships through improved mutual understanding.

FIGURE 2: Part of a consultative community talanoa in operation

Cultural humility

Cultural humility recognises more ways than one of understanding any given situation. Attributes attached to cultural humility include “openness, self-awareness, egoless, supportive interactions, and self-reflection and critique” (Foronda et al., 2016, p. 210). The methodology of the research supports cultural humility through talanoa and attention to va because relationally orientated safe spaces encourage self-reflection, selfawareness, and the appreciation of others.

The research

Four research questions guided our work:

- RQ1: How do Pacific voice and concepts lead to teacher learning through cultural humility?

- RQ2: How are the benefits of Pacific-informed teacher learning shared with students?

- RQ3: What are the impacts of Pacific-informed changes in teachers’ practice on Pacific students’ educational experiences?

- RQ4: What are the dynamics that support the translation of improved Pacific students’ educational experiences to other valued outcomes?

This nest of research questions investigates what is valued as Pacific student outcomes in education by researching what local communities care about and mapping the effect of this knowledge onto changed teacher practice. The research questions (RQs) imagine education as a journey in which KA provide broad and coherent access to Pacific communities and the schools that serve them without regard to children’s ages, so that consistency of approach and long-term deepening of relationships between educators and community can be facilitated.

Research activities

A solid relational platform for the research was established at the start of the 2021 year. Steps were made to recruit Pacific teachers and others as “cultural brokers”; teachers as team facilitators; and as practitioner participants. Using our existing relationships with Pacific communities and staff of each KA, we began a process to engage the wider Pacific communities in each site through a cultural broker. A cultural broker in this context refers to a member of the KA Pacific community willing and able to work in the space between the KA and Pacific community members. Potential brokers were approached through pre-existing relationships and community members subsequently shaped the role in context. In one site, this involved a committee of Pacific teachers adopting the role; in the other, a group of Pacific parents with pre-existing relationships across the KA became brokers who advised on research design and consultation methods. Teachers in each KA were identified in-house as team facilitators through the staff members we had initially approached in consultation with KA leaders. Their roles included booking rooms for PLD meetings, interfacing with the cultural brokers, and managing communications with KA and community members at the local level. Practitioner participants self-identified as a result of calls to KA staff managed by the team facilitators.

Participants

Demographic information from teacher participants across both sites reveals that all self-described as female and all bar one were of New Zealand European or Pākehā origin. Most were experienced teachers, although one Year 1 teacher took part. The split between primary and secondary teachers was 11/7. Four were members of senior management teams. Two attendees were Learning Support Coordinators, one based in primary and the other in secondary education. An interesting feature was that many had previously experienced life in other cultures. For example, one had taught in Myanmar, another in Torres Straits Islands, and one was married to a Samoan. In addition, many had longstanding commitment to Pacific communities through education, often as long-serving teachers in their current schools. These factors may have contributed to their desire to participate, and also the cultural humility observed by the researchers.

Following common recruitment processes, research activities varied between the two settings.

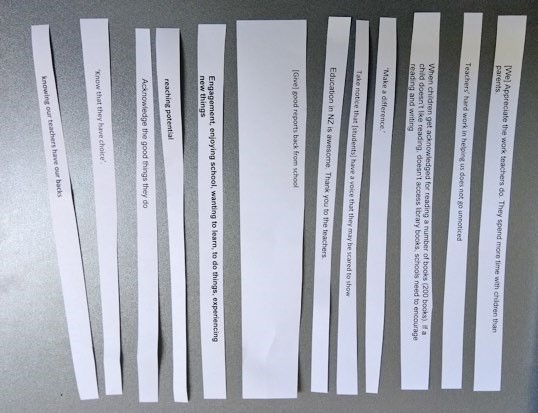

FIGURE 3: The Learning From Each Other research process

Site 1, Year 1

At Site 1, cultural brokers facilitated dialogue between KA Pacific communities, schools, and the research team with the result that around 100 people attended a community fono (meeting). The fono was an evening of celebration that included speeches, dance, song, and food. Multiple talanoa took place among parents (and some students and wider family members) in small groups with a Pacific parent or teacher acting as scribe. The fono produced a rich information set for subsequent discussion.

FIGURE 4: Community fono celebratory meal

The analytical process involved sorting the information into themes. This was achieved by the research team and guided by two principles. The first was to recognise the Pacific wisdom of previous consultation processes with Pacific communities such as those behind Tapasā (Ministry of Education, 2018) and the Action Plan for Pacific Education (Ministry of Education, 2020), and more general literature (Chu et al., 2022). A broadbrush approach to such literature suggests the saliency of Pacific language, culture, and identity; experiences of schooling that can be negative; relationships; and Pacific community aspirations. The second principle was practical—using our experience of teacher education in schools to provide suitable focuses for the five PLD sessions provided for in the research design, leaving the final session for teachers to organise around their accountability.

As a result, the information gifted by Pacific parents and community members (including some students) was coded and sequenced into five themes.

- Pacific cultures and identity

- School culture and issues with schooling

- Pacific student–teacher relationships

- Pacific parent–teacher relationships

- Ideas of success.

The team facilitator arranged space and times for six PLD sessions attended by seven teacher participants from the KA, one session for each theme and a final sharing meeting. These 2-hour sessions were exercises in sense-making of Pacific parent voice by teachers supported by the researchers and, on occasion, an “outside” Pacific person. “Outside” here means outside of the KA. The opportunity to hear stories of Pacific people’s educational experiences and perceptions from other contexts assisted participants to recognise patterns sitting behind the local voice to which they had access, pointing to systemic matters that required challenging in their local settings. Participants valued being able to ask questions in the safety provided by this aspect of “outside” voices, testing their developing understandings and seeking challenge or validation.

A typical PLD talanoa involved a recap through which teachers reflected on their previous learning, the presentation by the researchers of themed information from the community talanoa, dialogue about the significance of this information, and opportunities to reflect on new learning and ways the teacher participants could respond or had responded—and what had happened. At the end of the year, the teachers reported back through a presentation to the KA on their learning, inviting others to join in Year 2.

FIGURE 5: A sense-making cut-up activity from a PLD session

COVID severely disrupted this year. On two occasions, the research team left Wellington to find the country locked down on arrival in the South Island. Digital talanoa replaced some face-to-face sessions. At times, teacher participants or families were sick and unable to attend online. The intended mid-point report back to parents was truncated to a message in school newsletters.

Site 1, Year 2

We planned a second group of teacher participants in Year 2 supported by tuakana–teina relationships involving teachers from the first year. However, the interruptions from COVID had restricted Year 1 activities. More importantly, teacher participants explained that they felt they had only “scratched the surface” and wanted to continue learning. One new member joined but the group took responsibility for feeding KA professional learning groups with the knowledge they acquired as they continued to interact with the research team and Pacific communities. This development was welcomed because deep and lasting relationships can produce sustained change.

Thus, in Year 2, the team facilitator and teacher participants organised three whole-day PLD workshops. These involved learning from a Pacific artist, teachers, and students; and included a shared session of drumming with Pacific primary school children, access to a Pacific resources expert, a visit to a Pacific early childhood education (ECE) setting, and explanations of “what counts” from Pacific secondary students.

FIGURE 6: Pacific resources PLD session

Teacher participants learnt from the words, actions, aspirations, and prayers of those they encountered. The learning from Year 1 challenged them in Year 2 to think about fundamental concepts such as space, time, and success, and their own roles in supporting Pacific success in a wide range of forms. Year 2 closed with a liturgic celebration of what had been achieved in which the participating teachers explained their learning and actions to members of the Pacific communities of the KA. Thankful parents asked for continued commitment and further teacher learning.

FIGURE 7: Teacher-participant/Pacific student drum workshop/PLD session

Site 2, Year 1

As with Site 1, cultural brokers facilitated dialogue between KA Pacific communities, schools, and the research team. Unfortunately, two community funerals restricted attendance at the initial fono. An additional fono was organised and 10 Pacific parents and grandparents attended. Different experiences were offered from the talanoa across the two diverse settings; for example, “Warmth and family are important at school as well as at home” (Site 1) and “Make them feel loved at school like they are at home” (Site 2). However, many underlying aspects resonated across the contexts—such as the significance of matching care at home with care at school, visible in the example given. The pattern of PLD delivery in Site 2 followed that of Year 1 in Site 1. The final session of the year included a performance by the Pacific student group of the host school to complement the participating teachers’ feedback. Two participants offered a slide show of what they had done, detailing deliberate changes they had made in their practice and pointing to the effects of this on children in their classes and their relationships with Pacific parents. Others offered storied accounts of new thinking and actions based on this. More opportunity to celebrate Pacific cultures was an element in the fono talanoa for this centre.

FIGURE 8: PLD talanoa in session

Site 2, Year 2

In Year 2, a second cohort of teacher-participants was recruited through tuakana–teina relationships. The PLD sessions ran in a similar way to Year 1. However, the discussions were more beneficial to the second cohort of teachers because the researchers knew what had been learnt by participating teachers in the initial year. This enabled some sharpening of the process. Pacific community members also attended. Year 2 was greatly delayed due to the effects of COVID 19. These effects included a scarcity of relief teachers, unwillingness of schools to release staff from classes already significantly disrupted, and the desire to regain stability of curriculum delivery. The closing protocols for this centre involved the researchers and some participating teachers attending a Pasifika Connect session with members of local Pacific communities.

FIGURE 9: Pacific students use a final PLD session as an opportunity to perform

Analysis

Transcribed PLD fono were coded through Informed Grounded Theory (IGT) (Thornberg, 2012) using NVivo 1.7.1. Focusing on this data set reflects the aim of the research to examine the potential of Pacific voice to effect changes in educational practice through teacher learning. IGT assumes that researchers take conceptual information and experiential learning into analysis thereby affecting the process. In relational research, this is an accepted reality that can be turned to advantage. Researchers can “inform” their analytical strategy by testing sensitising concepts for usefulness at the first stage of iterative coding. In this case, significant concepts derived from parent voice and supported by the literature included time, space, and relationships. These proved productive in analysis for first-level coding. Second-level coding within these areas centred teachers’ learning; sharing the benefits of learning; the effects of benefits on students; and the dynamics involved. In the next section, analysis of PLD talanoa provides answers to the RQs. Because talanoa is a discursive and iterative form of dialogue, examples of responses are woven together across the various spaces and times of the PLD sessions demonstrating the kinds of learning occurring as a field rather than as case studies.

Major findings

RQ 1—Focus: How do Pacific voice and concepts lead to teacher learning through cultural humility?

Analysis of teachers’ PLD talanoa points to the significance of accepting challenges to current understandings, practices, and postures; and new understandings matched by steps towards change. These two processes are related because accepting challenges to the status quo creates space for innovation informed by learning. What follows are examples of these dual processes in the key areas of relationships, time, and success.

Relationships

The literature makes clear the significance of teacher–student relationships in the education of Pacific students (Averill, 2011; Chu et al., 2022; Flavell, 2019; Hawk et al., 2002; Siope, 2011; Spiller, 2012). Fono talanoa provided specific examples and emotive language to help teacher participants to understand what that might mean. For example: “It’s about how you relate to the child—that goes beyond language and culture and to the heart. The bond means that you know that child. It’s always about the relationship.”

Stories from the PLD talanoa suggest that teachers can learn to re-think their educational relationships by encountering Pacific voice, especially when sharpened by Pacific thought (such as a brief introduction to Pacific concepts such as va). Thinking through va directs attention to the environments in which relationship are staged. As a consequence, teachers’ understandings of, and reaction to, student behaviour in specific spaces can be revisited.

In the following two examples, quietness, an attribute stereotypically attributed to Pacific students (Spiller, 2012; Vuni & Leach, 2022), is unpacked through environmental and relational thinking, pointing to the agency of teachers to instigate change. A key step in the change process involves the cultural humility to learn by reinterrogating familiar situations.

In the PLD talanoa, opportunities occurred for teachers to be explicit about links they were making between self-examination and conceptual knowledge. For example:

If we go back to the va, it made me go away and really think about why a couple of students … didn’t really put their hand up … didn’t speak to me …

Questioning the meaning of previous experience can feed the process of using new ideas to deliberately shape new practice. For example:

Thinking about relationships with kids I taught in years before … [ I am learning] if they know they can communicate when things are good for them the academic relationship is better—if they know they are not going to be judged if they are having a hard time. It takes time to work towards that …

As might be expected, teachers spent considerable time in the PLD talanoa thinking about their relationships with students and new actions to promote reconfigured, closer relationships.

Examples from the PLD talanoa also show that parent–teacher relationships are a context for the dual learning process of challenge and change. Parent–teacher relationships are significant for the way they shape Pacific parents’ access as contributors to effective Pacific education (Chu et al., 2022; Fairbairn-Dunlop, 2022). Pacific parental voice from the fono talanoa portrayed discomfort in school situations. This challenged teachers to rethink the forces at play. As a consequence, new postures of responsibility for reshaping parent– teacher interactions became available to teachers. When teachers accepted challenges to habitual practice, this prompted ideas that reframed the foundations of parent–teacher relationships:

As teachers we need to communicate, open up power sharing in our environment, they [Pacific parents] don’t have to wait for formal interviews … it’s [good to make contact and] not always when things go wrong … We need to be opening up the four walls of the educational classroom …

When matters such as power, timing, and partnership become visible as significant in relationships, this can redefine the ways teachers carry out their professional roles. For example, one school leader described new deliberateness in moving from one space to another in order to follow a relational agenda:

My other thing was connecting with parents to talk to them about their children, how well they’re doing. So, I made a point of … standing at the gate more often and talking to people, not just Pacific parents … and it’s amazing how many good things you can think of that’s been happening throughout the day talking to parents through that way.

In this case, changing practice means moving from a “professional space”—the school office or classrooms— to a shared space defined as important by who is present. This move promotes enhanced communication because it increases time spent together.

Time

The literature points to the significance of time in the education of Pacific students. For example, progress is characterised as walking backwards into the future (Sanga et al., 2023), linking the past to the future through the present. In addition, relationships are enhanced by time spent together (Siope, 2011). Significantly, education can be understood as a long-term malaga (purposeful journey) (Anae, 2019; Reynolds, 2017; Surtees et al., 2021) rather than as short episodes like a lesson or assessment. Cultural humility is displayed when teachers recognise and value that there are many ways of understanding and living well in the world. This is especially powerful when such fundamental concepts as time are in focus.

In the PLD talanoa, teachers were challenged to rethink time by information derived from Pacific parents at the fono talanoa. For example: “The children are very busy … It’s a big part of who they are on the inside. It’s not having time off—they are busy being who they are …”

The prevalence of time in the fono talanoa prompted dialogue about time in the PLD talanoa. This included self-awareness of time as an expression of cultural values. An example is:

… being a New Zealand Pākehā, time has always been a super important thing—being on time in the family … that’s what you learn to do. And in my cultural group that is seen as respect, you know? It’s just being aware that you have your own values.

In addition, by being drawn to talk about time, teachers recognised their agency to change time use. One example is the exploration of the familiar situation where attention-seeking behaviour is rewarded with teacher attention despite the inequity this may produce.

In this story, a teacher recounts how working to change relationships with Pacific students in her classroom enables her to re-allocate time more equitably:

So, unless I went around and noticed that they needed support, I’d only be going to the kids who are demanding it all of the time … Whereas now, they [Pacific students] don’t mind coming up and finding me … I think it’s my desire to know more and to create opportunities for [my] quiet Pacific students to share [their] depth of knowledge, and to feel comfortable enough to do that …

Teachers also recognised the intergenerational significance of time that underpinned statements from the community fono such as: “Parents may not have had a good experience at school—they may not want to approach schoolteachers.” Such statements challenged teachers’ previous understandings of parent–school relationships, revealing submerged deficit explanations for familiar situations that absolve teachers of responsibility. Another example suggests the way teachers can appreciate how their own ideas about and experiences of time, availability, and involvement in education when applied uncritically to others can result in deficit understandings presented as “fact”:

We have to get away from the ‘fact’ that if they [Pacific parents] don’t make an appointment it’s not [that] they aren’t interested …

Rethinking the reasons behind common situations offers teachers opportunities to acknowledge past experiences as relevant to the present. Acknowledgement of the past also places responsibility on educators to find pathways towards positive change. As one teacher put it:

We need to address the pain Pacific people feel in education—through relationships— to support healing …

These examples that are centred on time show how the dual process of Pacific voice-driven challenge and teacher-originated change can encourage an understanding of Pacific education that stretches beyond the here and now. The result is that responsibility for mediating the effect of the past can be accepted by teachers.

Success

Pacific success as Pacific (Alkema, 2014; Reynolds, 2017; Toumu’a, 2014) in the literature refers to success defined by Pacific people by and for themselves. In education, this includes cultural, social, and academic forms of success. Success framed as academic achievement is a staple in education. However, ideas of success in education that move beyond achievement featured in Pacific parent voice from the fono talanoa. For example: “Success is when the child is present, and they are proud to be themselves.”

Pacific ideas of success challenged teachers to rethink their previous ideas and embrace success as a culturally informed matter. For example:

We have quite set ideas I think on what success is. It can be that you live in a big house, got a good job … and if that’s what we’re measuring, I think the government [was] measuring success in National Standards … If [Pacific people are] representing their family and their church, that is success for them.

There is evidence in the PLD talanoa of teachers challenging individually centred ideas of success in favour of relationally held success, appreciating the significance of collectivity to the Pacific parents:

It’s a communal sense, it’s not your success, it belongs to everyone, to the ‘village’ …

Given the prevalence of diverse notions of success, teachers also recognised the role of Pacific people to support them to understand what matters to communities in education, and teachers’ responsibilities to change practice so as to deliver a range of valued outcomes:

[We need to be] asking what parents and children see as success and changing our practice to achieve this.

[What] the parents want us to take away is all our families don’t have the same values, and don’t have the same desires, don’t see success as being the same thing. So, it’s important that we have conversations that you can get to know us, and what’s important to us and our family because it is so different.

One teacher encapsulated their new philosophy for producing the conditions for Pacific success as Pacific in a short mantra. This shows how consultation with Pacific parents as a result of involvement in the research has developed new guiding principles for her:

I filtered it down for me to make it really intentional, into three words that have changed my interactions … making them more explicit. So, I came up with, this is just for me, ‘understanding, co-instruction and intention’.

These discussions of success do not revolve around the replacement of one form of success with another. It makes no sense to reduce “Pacific success” to a check list because Pacific communities are diverse. In the research, teachers negotiated with the idea that shared success is informed by relationships, and that relationships are grown through shared time.

RQ2—Focus: How are the benefits of Pacific-informed teacher learning shared with students?

Much of the challenge offered to teachers in the PLD talanoa involved them rethinking relationships and, as a consequence, their role as a teacher. This includes reconsidering how time is viewed and used, and what matters in education. In this section, examples are given of specific changes in individual teachers’ practices and the benefits the teachers observed for their students. The examples, which deal with the benefits of sharing time, moving space, and sharing power, illustrate the way teacher learning and deliberate action can enhance the conditions for Pacific student learning.

The benefits of sharing time

Time is a valuable resource in education—there never seems to be enough. In this example, one teacher describes their action to provide extra time in their secondary classroom. However, the dynamics of the classroom have been shifted. The seed for this change was sown in the PLD talanoa by Pacific parental aspirations for their children such as: “Make them feel loved at school like they are at home. Even if they aren’t getting it at home, show them love at school …”

This teacher organised time for work-focused relational activity after school because of their dissatisfaction with previous outcomes. The primary aim was to deepen relationships in order to encourage achievement:

I think that came down to stopping what wasn’t working in class. And for me, it was setting up that time outside of class to really have that connection with the students who academically needed it … I started doing after school Friday sessions … Now people know about it they come around because we have biscuits, but we really have some good chats as well … they are starting to achieve because they have that connection whatever is happening in class. I haven’t figured out how to change that in-class relationship yet.

This account shows that, although the additional time is spent in the same place as timetabled time, different relationships can be indicated by changing aspects of the physical environment. Here, a shift is signalled through food (which cannot be consumed during school-defined time) and the sanctioning of informal dialogue (a contrast to the “normal” expectation of staying “on task”). The benefits the teacher claims for the students include deeper connection between student and teacher, opportunities to further connect with other students, and enhanced achievement. The teacher is aware of a need to explore reshaping schooldefined time so that the gains for students available from the Friday afternoon extra sessions over which the teacher has direct agency can be extended within institutionally defined structures.

A second example comes from primary education and shows how Pacific students benefit when teachers share decisions about how class time should be spent. In this narrative, the teacher facilitates the teaching of a Pacific language, Tongan, in their classroom:

So, another thing that I thought of … that’s kind of about honouring who you are … We have two hours I said to the kids ‘You can choose whatever you like to focus on’… Anyway, one girl said, ‘I’d like to learn some Tongan’ so she can speak to her grandmother … So, we organized for [a senior student] to come down and spend half an hour, twice a week working with this one student, which has been awesome …

The teacher explains their deliberate act as “honouring”—a matter of identity that feeds the kind of cultural pride that Pacific parents in both fono talanoa included in Pacific success. The elements of the situation are freeing up time for student choice; respecting the student’s aspirations—to talk to her grandparent; and providing leadership opportunities for a Tongan-speaking student. As facilitator, the teacher has sourced expertise from the community, relinquishing the habitual teaching role as expert. Benefits to the Pacific student in the class focus on cultural wellbeing, increased ability to communicate with family, exercise of agency, and language learning. Benefits for the Tongan tutor, also a student, include leadership, relationship building, and the validation of language fluency as a skill valued in school.

The varied experiences of success in these examples are both contingent on the teachers deliberately sharing power and creating a partnership. Through partnership, because the strengths of all are valued, teachers can more easily care for the relationships between Pacific students and their language(s) (Kennedy, 2019) as well as peer relationships and relationships and those between students and teachers.

The benefits of rethinking space

The PLD research data showed how understanding information from community talanoa by considering relationships as va or relational space can lead to changes in physical and relational space which benefit students. These benefits can be direct and indirect. A direct benefit of teachers learning to rethink their use of space is the effect change has on specific students.

When teachers act deliberately and consistently to increase proximity with Pacific students, changes in the student–teacher relationship can produce positive benefits in students’ behaviour. For example:

So, one of my things was … getting alongside our students. So, one child in particular is quite quiet and I never really heard his voice, his strong voice. Getting alongside him is really effective. So, I’ve been doing it a lot, and he’s become a bit more brave in class to give me his opinion and his thoughts. So that’s been really good.

Here, the teacher seems to have responded to Pacific parental comments from the fono talanoa such as “Take notice that [students] have a voice that they may be scared to show” by shaping their own actions in the classroom. The benefit to the student is visible in terms of enhanced participation and engagement, summed up by the teacher as bravery.

A second example shows a similar benefit of a teacher’s deliberate action:

We talked [in the PLD] about getting alongside your children, you’re talking to them rather than putting them on the spot on the mat and I’ve been trying to do a lot more of that. And that’s been working really well, especially with this one wee girl I’ve got who, she won’t answer so much on the mat but if you have a wee chat to her … then she’s just been putting her head on my shoulder …

In this example, the benefit to the Pacific student from the teacher’s deliberate re-use of space is a sense of comfort and trust made visible through their reciprocal desire for closeness with the teacher.

Indirect benefits to Pacific student can acrue when teachers act to curate closer relationships with Pacific parents. Teachers’ desires to care for relational space can be signalled when they reconfigure physical space and challenge norms that reinforce a view of professionalism that is expressed as distance.

The next example shows how reciprocity can be developed by rethinking space:

I think if I had that conversation [about a student’s issue] behind the chair, it would’ve been quite cold. Whereas because we get to sit side by side on the little kids’ couch … we were really close, we were kind of knee to knee, she had her mask on and … it felt like I was talking to a friend—or it changed the relationship I feel. And then as things have come up, it’s opened up that conversation … I can actually flick her a wee email and tell her about things that have happened. Whereas before … I think it would’ve been very defensive back. Whereas now it’s like, ‘Oh yes, we’ve noticed that happening too, have you tried this? Because this works at home when he does that.’

The benefit to the Pacific student comes from the way reciprocation feeds increased alignment between home and school. The teacher’s concern has been heard in an environment shaped by them to reduce threat and enhance connection. In the teacher’s view, a result is the sharing of successful strategies practised in the home by the parent. The student is likely to benefit from closeness between home and school that can channel feedback and feedforward and if the teacher uses specific strategies in school that are effective at home.

RQ 3—Focus: What are the impacts of Pacific-informed changes in teachers’ practice on Pacific students’ educational experiences?

Beyond benefits to individuals described above, analysis of the PLD talanoa reveals three main impacts on Pacific students’ educational experiences of new deliberate practices by teachers. These are steps towards the normalisation of being Pacific in the classroom; greater inclusiveness leading to heightened representation of Pacific people in school contexts; and the development of an agenda of consultation.

Normalisation

Education in New Zealand has a European origin and, despite policy movement towards biculturalism (Lourie, 2016), generally offers monocultural educational experiences. Where non-dominant cultures such as those of Pacific origins are present, there is a tendency towards exoticisation of minority cultures. An example is the calendar of Pacific language weeks which, while worthwhile and important, are limited in their influence on education as a whole. Normalisation, where something becomes part of everyday educational experiences, is a process that takes time and effort. In normalisation, consistency indicates value so that no one is surprised when what was new is now frequently experienced.

During the PLD talanoa, teachers described many ways they were working at a small scale to make sustainable changes—the kinds of changes that can lead to normalisation. Examples include creating Pacific language ink stamps to sit with English and Māori stamps as a means of celebrating good work. In this case, the teacher described giving students the choice of stamp. Award certificates in Pacific languages were developed across one school, and spelling strategies were augmented to include Pacific words such as the Samoan fale so that comparison (with whare) became a way of paying attention to language as an entity. The teacher concerned reported children enthusiastically contributing words from other heritage languages to lessons.

Another example of normalisation can be seen when children’s interests are recognised in the classroom as valuable learning experiences for everybody. An example of this process concerns one child’s interest in drumming:

[The student] wanted to show his drumming, so he got up, and he’s got a bit of a difficulty with speech, but I’ve never seen him so articulate, such great diction, such great clarity as when he was explaining how the drums worked, and when you push on a different beat, and the kids were just fizzing …

Student agency can lead to the normalisation of being Pacific when Pacific students have the confidence in learning environments to bring their skills, knowledge, and experience to the table.

Inclusiveness

Normalisation is linked to inclusiveness. Examples of teachers acting to change Pacific students’ educational experiences by encouraging participation have been offered above. Two other forms of inclusiveness, both involving family members, suggest the range of possibilities teachers investigated during the research. Firstly, a teacher reported researching Pacific family members’ names for use in mathematics lessons in the primary sector:

I did some little bit of investigating of some names of relatives, in our maths we sort of put [name], ‘Oh that’s my grandma’, and ‘Oh that’s my little brother’, and that was just wasn’t anything much different, just made a conscious effort of using all of the children’s names, not just the Pasifika kids … they became more invested, it was just like an extra 10% of that without extra work.

The family became “included” in the mathematics work, eliciting positive responses from the students. The strategy seems to have shifted the learning from being potentially abstract or disconnected to a known, domestic normality, enhancing engagement. The value of this kind of inclusion has been noted elsewhere (Hill et al., 2019).

A second family-centred example involves teachers creating opportunities for Pacific parents or family members to be physically included in the class for their expertise and commitment. The example shows that teachers can develop inclusive partnerships with Pacific parents when they learn to behave in invitational ways:

I had one of my parents come up … she said ‘Oh I’ve got a little wee YouTube about … making tivaevae (quilts) with the flowers … and my daughter—could she share it in class?’ I said, ‘Look, if you’d like to come and join us … it would be wonderful … Don’t tell me now, just go and have a think about it and let me know when that would suit you.’ … And she came in full Cook Island dress … and she brought this beautiful tivaevae that was off her bed and showed the kids how to make it …

Although the first move was made by the mother offering a video, the teacher sought an opportunity for the parent to be personally involved. Her learning about time and the time commitments of cultural business meant that the teacher did not deliberately suggest a time slot for the parent’s contribution, but constructed a “pause” so that control of time sat with the parent. As a result, the parent’s involvement was much more extensive than the teacher had imagined, and the educational experience of the class was transformed as a result.

Consultation

A further impact of Pacific-informed changes in teachers’ practice of benefit to Pacific students involves consultation. The development of a consultative agenda implies a culture of asking and the deliberate creation of opportunities through which this becomes possible. During Year 2 research at Site 2, an opportunity was created through prayer. Pacific students were offered the chance to open a PLD session— which they knew was intended to benefit them—by offering prayers for the kinds of teachers and education they needed to learn best. This provided learning for the teachers about what was significant to those Pacific students and the kinds of language teachers might use to mirror the children’s concerns when discussing teaching and learning with them.

Another example involves teachers constructing partnerships with Pacific parents in curricular and extracurricular matters. The teacher explained:

A result of the work we have been doing here, over time, is that we have the relationship now where I was able to say, ‘I would still like us to do a Pasifika cultural group [despite COVID] and would you help me?’, and she [a Tongan parent] said, ‘Yes.’ And when we got together—she was part of the whānau group that helped here [with the fono] and that relationship has grown—her as part of a link to the community as well, she made a video of bread making and used the Tongan values and we used that in school …

According to the teacher, as well as the performance group and bread making, the dynamics involved in this encounter stretched over a long period of time and into the wider Tongan community.

A final example of an agenda of consultation is of a school leader using what she had learnt through the research talanoa process to be more inclusive, fostering the comfort of Pacific community members, and thus encouraging their active participation as consultants:

We had … a strategic board meeting last night and all our different cultural groups introduced themselves with pride in who they were. They introduced and they said, one said their name and that ‘I’m a Cook Islander’ … So, there’s those things that, because we’re talking about it [Pacific involvement in education] all the time that’s showing that it’s valued, and we’ve got that idea and it’s made me think in terms of our … cultural community strategic goal. We had that strategic meeting on what that’ll look like next year. So, that’s been my learning …

The active participation of Pacific people at board of trustee level is essential if Pacific community voice is to reshape the educational experiences schools provide.

RQ4—Focus: What are the dynamics that support the translation of improved Pacific students’ educational experiences to other valued outcomes?

The first three RQs have been answered by indicating the range of what was learnt from Pacific people during the research by teachers, the benefits of that learning to Pacific students, and by taking a wide lens to the way Pacific students’ educational experiences were impacted. RQ4 is now answered by identifying the dynamics that support outcomes valued by Pacific people that stretch beyond educational experiences.

Two valued outcomes are sustainable change—that which is likely to last and potentially multiply; and learning of the “heart and mind”—that which is deep and transferable as contexts change. The dynamics that support these valued outcomes include teachers’ enhanced confidence to be positive, well-informed actors in Pacific education; attention to the small scale and every day; reflective, experiential learning; and time.

Confidence

Confidence to navigate cultural matters is important for the achievement of sustainable change because confidence sits at the heart of partnership between educators and Pacific people. At the start of the PLD process, some teachers expressed concern at saying or asking “the wrong thing” of Pacific contacts and they were also worried about being judged as “tokenistic” by teaching colleagues. Moving away from this fear-centred double bind was made possible by teachers’ increased confidence in themselves as learners and sense-makers. Their confidence was fostered by the safe space of talanoa, expressed by one teacher as follows:

I immediately think is this is being a really safe space … and I think when we have stupid questions … that it’s okay to not shame us when we ask.

However, confidence also grew through spending time with Pacific people, itself supported by confidence from the talanoa process. A clear example of is a teacher who attended a Pacific-focused workshop for Pacific parents in her local area. She told the talanoa group:

I put myself [out] on Sunday and I went to the Talanoa Ako … it was about the workshop with parents, caregivers of Pasifika students. And I was really nervous, ‘Am I going to be the only person there? Will they all be speaking in Samoan? Will I be welcome?’ It was the most invigorating thing I’ve done for a long time. Lots of kai, lots of supportive engagement and … Yeah it was great to find something like that out there …

This example illustrates how the research process encouraged relational confidence, and how the risks that this permitted produced a reward likely to inspire further action.

Scale

At times, it can be attractive to seek a silver bullet, a big development to solve complex problems such as how to improve education for Pacific students (Smith & Wolfgramm-Foliaki, 2021). Silver bullet thinking can lead to deficit theorisation when simplicity leads to a situation where responsibility for complex issues is avoided by those who benefit from the status quo.

As a result of silver bullet thinking, some teachers’ confidence was tested when they had to withstand the expectations of their school leaders for a “special programme”, a simple, shallow, quick gain to justify involvement in the research PLD. At one juncture, this led to the doubt-ridden question, “Am I missing the point?” from a teacher whose changes in everyday practice appeared effective in the classroom, but inadequate as a silver bullet. After reflection and talanoa on the issue, another teacher highlighted the value of the small scale thus:

Learning little things like sitting beside has made a really big difference to the Pasifika students in my class, and not only them actually; it’s been quite helpful for other students. I feel like it’s taken so long to kind of get there butm… now I’ve gotta pass that information on …

Small-scale changes to classrooms and schools that are aligned with a relational understanding of the world, embrace and value Pacific cultures, and express progressive steps towards authentic partnership with Pacific communities and parents are significant. Together, small changes provide a “big” challenge to education as a system to rethink how to better serve Pacific students.

Experiential learning

Experiential learning supports the sustainability of valued outcomes from the research. This is because the learning undertaken by the teachers in the PLD talanoa does not address a quick generic fix but is localised and demands that the teachers involved performed contextualisation themselves. Learning from local parents has its own value for teachers:

Hearing these things from Auckland … is interesting. But hearing from our own Pacific parents is powerful. We fit it immediately into our setting. We think ‘Oh, what can we do about that?’ … it helps us imagine what it’s like here.

This claim points to the value of the mediated dialogue process which made available to teachers the voices of Pacific people from their local communities. These voices included the parents of Pacific students being taught now in the KAs. The PLD was structured to encourage the teachers to learn about their own students:

We weren’t learning about a programme, we were learning about who our students are, what our students and parents want, and about what we have to do to make learning a better experience for them.

Teachers-as-learners who have experienced the value of engaging with the Pacific communities served by their school are on a path to sustainable change because the process is iterative and dynamic.

Sustainability is also supported through the discursive nature of the talanoa process experienced by teachers in Learning From Each Other. Through the talanoa process, teachers learnt to value and explore their own expertise as a helpful way of appreciating the lives of their Pacific informants. This included reflection on cultural matters, such as this example which formed a backdrop to discussion a Pacific culture:

I would say I don’t have a culture. I’m kiwi so. But my son’s best friend broke his ankle, … So, I did what I always did, and I put treats in there … put all these things in a bag … And they were like ‘Here goes the Irish Catholics … she goes, that’s what the Irish Catholics do’. And I didn’t realise but that was how my mom had brought me up, my nana, and it would be Irish Catholic, but she said it stood out to them because she said the Scottish don’t do that … I was like ‘Oh that might be my culture but hadn’t thought about that’.

Because the talanoa process legitimises everyone’s expertise, teachers placed ideas of their own culture beside expressions of culture from Pacific people so that neither was denigrated or exoticised. Instead, an appreciation of difference and space for the viewpoints of others became possible. Where difference is valued, a one-size-fits-all understanding of life becomes untenable. This thinking is valuable in all contexts:

I think for me it was realising last week when I was having to be with people who were talking about the COVID immunisation rates and commenting about Māori and Pasifika, and [saying] ‘What do you mean they want it done differently?’ etc. … and I was able to say ‘Hold on!’, and I just felt … a lightbulb moment for me actually of putting myself in someone else’s shoes.

Time

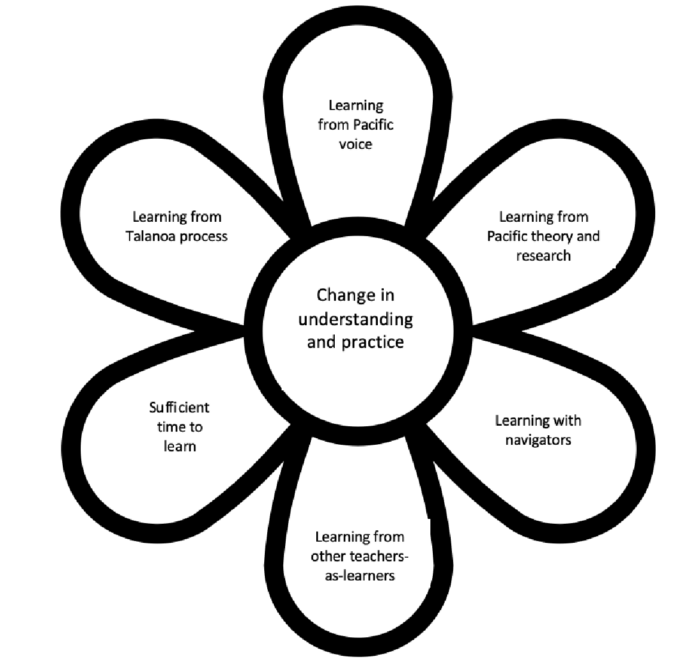

Many aspects of the framework derived from Learning From Each Other are visible in The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) (Ministry of Education, 2007) which states “while there is no formula that will guarantee learning … in every context, there is extensive, well-documented evidence about the kinds of … approaches that consistently have a positive impact”. Among these are elements central to the talanoa PLD approach we employed, including “create a supportive learning environment; encourage reflective thought and action; enhance the relevance of new learning; facilitate shared learning; make connections to prior learning and experience; and inquire into the teaching–learning relationship” (Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 34, punctuation altered). These elements were consistent across Site 1 and Site 2. Leaning on this consistency, capitalising on similar thinking across sites, and because the aim of this report has been to demonstrate the range of responses, much of the narrative has woven data from both sites of the PLD talanoa. However, NZC also advocates for “sufficient opportunities to learn” (p. 30). Given the difference in structure in Year 2 of the initiative discussed in the Research activities section above, a contextual approach to sufficiency when considering the dynamic of time is helpful.

It appears that those groups in Site 1 who spent Year 1 or Year 2 in the research programme had sufficient opportunities to learn from Pacific parents through information contained in the fono talanoa and to apply this in interactions with Pacific students and parents. That is, they learnt and contextualised in their immediate environments.

However, while this was also true in Year 1 of the group in Site 2, the additional year this cohort spent engaged in the research demonstrated learning that extended into wider contexts, primarily focused on relationship enhancement with Pacific people in their communities. Examples include visiting a Pacific ECE centre, hearing the journey of a Pacific artist, and talanoa with Pacific students. The growth of participants’ confidence through experiential learning over an extended period of time appeared to contribute to increased ownership over the programme.

In relational research that values community engagement as a way of enhancing Pacific students’ education, this additional level of learning points to extended time as a key factor in research and PLD that seeks sustained and deep change in Pacific education. Experience suggests that, too often, PLD providers and schools expect deep change from short (and sometimes one-off) PLD commitments. However, it seems obvious that since the learning of students and teachers shares many similarities, the data-driven advice of NZC should be heeded so that time is extended as needed. Especially in contexts such as Pacific education where the issues are intergenerational, solutions do not resemble a silver bullet because deep change is required. As a consequence of the dynamics visible in Learning From Each Other, we developed the following model of the learning process to support deep and sustainable change.

FIGURE 10: The Learning From Each Other learning model

From Chu-Fuluifaga and Reynolds (2023a)

Conclusion: Implications for practice

#1 Schools can leverage the potential of local Pacific voice

Learning From Each Other points to the potential of local Pacific voice collected in culturally appropriate ways to:

- motivate teachers to devise changes that meet the aspirations of their local Pacific communities

- provide navigation as they devise new aspects of practice

- frame accountability related to the nature and effects of changes that are made.

Every school in Aotearoa New Zealand connected to a Pacific community has this opportunity.

#2 Schools can value small-scale but lasting changes

The research shows the catalytic potential of valuing a wide range of deliberate small-scale changes in practice achieved by teachers who learn from the powerful resources of Pacific voice and concepts, supported by navigators such as researchers. These include changes to:

- time allocation

- student agency

- the use and understanding of space

- curriculum content

- values

- relationships.

Together, such changes embody developments in school culture connected through Pacific-informed logic.

This implies the value of providing opportunities for teachers to achieve and then reflect on the value to Pacific students and parents of any small-scale changes they make. This is because scale and significance are relative and positional matters. Effective change need not revolve around a grand new initiative.

#3 Schools can shift valued outcomes by thinking deeply

The research shows the significance to relational and learning outcomes of shifts in logic achieved by teachers when supported by Pacific voice. Outcomes valued by parents and therefore by the research process include:

- Pacific students feeling supported in educational spaces

- the enhancement of Pacific students’ participation in education

- relationships between home and school that are moving towards authentic, power-sharing partnership

- peer support as a way of learning

- the increased visibility of Pacific people and Pacific cultures in educational spaces

- recognition of the expertise held in Pacific communities and ways for teachers to access this in order to enhance the education of Pacific students.

Implications that stem from this key learning centre on the significance of changing the logic used by schools and education more generally. This involves rethinking what is valued, how it is measured, and how accountability is constructed and justified as aspects of school (and educational) culture. Learning that disturbs the habitual gives creative, catalytic opportunities.

#4 Schools need support to link policy and practice to benefit their Pacific learners

Learning From Each Other exists in a field of Pacific community-informed policy and practice developments. For instance, the research supports teachers to achieve attributes ascribed to effective teachers of Pacific students outlined in Tapasā (Ministry of Education, 2018). Examples include:

- Confidence developed through the talanoa process produced teacher behaviour that “Demonstrates a strengths-based practice and builds on the cultural and linguistic capital Pacific learners, their parents, families and communities bring” (p. 11)

- Experience of talanoa and learning about va encourages thinking that “Uses … different Pacific conceptual models and frameworks as a reference and guide for planning, [and] teaching” (p. 15).

The research, therefore, provides a framework to support effective locally relevant delivery of PLD that can lead to the kinds of sustainable change valued in policy. The implication of this is that Pacific-focused PLD should consider the framework and dynamics identified in Learning From Each Other in order to maximise the change-making potential of precious resources such as time, teacher attention, and community-based expertise in PLD.

#5 PLD providers should appreciate the significance of context when supporting Pacific education

The research was deliberately sited in two different contexts. Although common themes emerged from the fono data collected in the two sites, there were relevant aspects of community contexts present in the way these themes were expressed as exemplified above. However, a more significant aspect of difference to the process and outcomes of the research centres on the educational contexts involved. As discussed, the dynamic of time varied between Site 1 and Site 2 because the participants in Site 1 wanted to continue in the research. Explanations for this include the coherence of the KA as a faith-based structure set amongst a community of common religious practice in which many relationships such as those between teacher participants and between school leaders/Pacific community members existed before the research commenced. The implication of this for the development of effective Pacific education is that relational groundwork within school and KA structures has great potential. This is because trust—especially when taking risks—benefits from relational closeness.

Acknowledgements

The research team thanks the participants—cultural brokers, Kahui Ako relationship brokers, participating school leaders, teachers, and support staff—of the Naenae Kahui Ako and Dunedin Catholic Schools’ Kahui Ako. We also thank those students who became involved in one way or another. We trust that the gifts of knowledge and hospitality extended by the Pacific communities involved have been reciprocated through learnings and consequent changes in education that honour the aspirations of our Pacific collaborators.

This final report includes elements of the following previously published articles written as interim reports on Learning From Each Other:

- Chu-Fuluifaga and Reynolds (2023a)

- Chu-Fuluifaga and Reynolds (2023b)

- Chu-Fuluifaga and Reynolds (2023c).

FIGURE 11: Research as celebration and partnership

Researcher biographies

Cherie Chu-Fuluifaga has led major transformative research projects to facilitate significant changes for Pacific learners across education in Aotearoa New Zealand for the past 20 years. She has developed an Appreciative Pedagogy that is positive and focused on bringing out people’s strengths. Cherie is creative in her methodologies and ways of developing learners to be leaders. Her research is focused on examining Pacific student experiences in tertiary education through the lens of Appreciative Inquiry [AI] as this relates to mentoring and leadership development. She publishes in New Zealand and international journals and books, aiming for impact and influence on Pacific communities, policy makers, and institutions. Cherie seeks ways to consolidate her position as lead and specialist researcher in Pacific mentoring, education, and leadership. She is currently Senior Lecturer in Education at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.

Martyn Reynolds has been a practitioner in state education for 35+ years in the UK, PNG, Tonga, and Aotearoa New Zealand. This includes substantial experience of supporting professional development and learning as Specialist Classroom Teacher in an urban high school in Wellington. He works in Pacific education research in the relational spaces between Pacific communities, parents, students, and teachers. In his PhD, he was an early pioneer of video mihi and dialogic research methodologies and is constantly and deliberately extending his knowledge of the vā, especially in pedagogic and research contexts. Martyn publishes with many co-authors across the Pacific region, working on leadership, traditional oralities as methodologies and building the capacity of regional colleagues. He works under the banner of Silvavaka Consulting and is a

Postdoctoral Fellow in Pacific Education Research at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington.

References

Airini, Anae, M., Mila-Schaaf, K., Coxon, E., Mara, D., & Sanga, K. (2010). Teu le va—Relationships across research and policy in Pasifika Education: A collective approach to knowledge generation and policy development for action towards Pasifika education success. Ministry of Education.

Alkema, A. (2014). Success for Pasifika in tertiary education: Highlights from Ako Aotearoa supported research. https://ako.ac.nz/ knowledge-centre/synthesis-reports/success-for-pasifika-in-tertiary-education/

Anae, M. (2010). Research for better Pacific schooling in New Zealand: Teu le va—a Samoan perspective. Mai Review, 1, 1–24. https://www.journal.mai.ac.nz/system/files/maireview/298-2299-1-PB.pdf

Anae, M. (2016). Teu le va: Samoan relational ethics. Knowledge Cultures, 4(3), 117–130. http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?p=AONE&s w=w&u=vuw&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA458164605&asid=79728fe582dc9574894712b26dbb6a7e

Anae, M. (2019). Pacific research methodologies and relational ethics. In Oxford research encyclopedia of education. https:// oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-529

Averill, R. (2011). Teaching practices for effective teacher–student relationships in multi-ethnic mathematics classrooms. Mathematics: Traditions and [new] practices, 75–81.

Baines, D. (2007). The case for catalytic validity: Building health and safety through knowledge transfer. Policy and Practice in Health and Safety, 5(1), 75–89.

Chu, C., Reynolds, M., Rimoni, F., & Abella, I. (2022). Talanoa ako: Talking about education and learning—Pacific education literature review on key findings of the Pacific PowerUP longitudinal evaluation 2016–2018. Hearing the voice of Pacific parents. Ministry of Education.

Chu-Fuluifaga, C., & Reynolds, M. (2023a). Learning from each other: A framework from the field. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (1), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.1526

Chu-Fuluifaga, C., & Reynolds, M. (2023b). Pursuing educational partnerships in diasporic contexts: Teachers responding to Pacific voice in their work. Merits, 3(2), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.3390/merits3020020

Chu-Fuluifaga, C., & Reynolds, M. (2023c). Teachers responding to Pacific community voice: Supporting relationships through an ecological research initiative. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-023-00285-4

Education Counts. (2021). Teaching staff. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/teacher-numbers

Fairbairn-Dunlop, P. (2022). Talanoa ako: Pacific parents, families, learners and communities talk education together. Ministry of Education. https://pasifika.tki.org.nz/Talanoa-Ako

Farrelly, F., & Nabobo-Baba, U. (2014). Talanoa as empathic research,Paper presented at International Development Conference 2012, Auckland, New Zealand

Flavell, M. (2019). Supporting successful learning outcomes for secondary Pacific students through home–school relationships. PhD thesis, Victora University of Wellington.

Foronda, C., Baptiste, D. L., Reinholdt, M. M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217.

Havea, E. H., Wright, F. T., & Chand, A. (2020). Going back and researching in the Pacific community. Waikato Journal of Education, 25(1), 131–143.

Hawk, K., Cowley, E. T., Hill, J., & Sutherland, S. (2002). The importance of the teacher/student relationship for Maori and Pasifika students. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 44–49.https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0716

Henry, T. M., & Aporosa, S. (2021). The virtual “faikava”: Maintaining “va” and creating online learning spaces during COVID-19. Waikato Journal of Education, 26, 179–194.

Hill, J., Hunter, J., & Hunter, R. (2019). What do Pāsifika students in New Zealand value most for their mathematics learning? In P. Clarkson, W. T. Seah, & J. Pang (Eds.), Values and valuing in mathematics education: Scanning and scoping the territory (pp. 103– 114). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16892-6_7

Ka’ili, T. O. (2005). Tauhi va: Nurturing Tongan sociospatial ties in Maui and beyond. The Contemporary Pacific, 17(1), 83–114.

Kennedy, J. (2019). Relational cultural identity and Pacific language education. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 18(2), 26–39.

Koloto, A. (2017). Va, tauhi va. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-532-7_19-1

Lather, P. (1986). Issues of validity in openly ideological research: Between a rock and a soft place. Interchange, 17(4), 63–84.

Lourie, M. (2016). Bicultural education policy in New Zealand. Journal of Education Policy, 31(5), 637–650.

Mila-Schaaf, K. (2006). Va-centred social work: Possibilities for a Pacific approach to social work practice. Social Work Review, 18(1), 8–13.

Mila-Schaaf, K., & Hudson, M. (2009). Negotiating space for indigenous theorising in Pacific mental health and addictions. Le Va. https://www.leva.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/negotiating-space-for-indigenous-theorising-in-pacific-mental-healthand-addictions.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media. http://nzcurriculum.tki.org.nz/The-New-ZealandCurriculum

Ministry of Education. (2018). Tapasā: Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners. https://tapasa.tki.org.nz/ Ministry of Education. (2020). Action plan for Pacific education 2020–2030. Author. https://conversation.education.govt.nz/ conversations/action-plan-for-pacific-education/

Naepi, S., Stein, S., Ahenakew, C., & de Oliveira Andreotti, V. (2017). A cartography of higher education: Attempts at inclusion and insights from Pasifika Scholarship in Aotearoa New Zealand. In Reid C. & Major J. (Eds.), Global Teaching. Education Dialogues with/in the Global South. (pp. 81–99). Palgrave Macmillan.

Reynolds, M. (2017). Together as brothers: A catalytic examination of Pasifika success as Pasifika to teu le va in boys’ secondary education in Aotearoa New Zealand. PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/ handle/10063/6487

Samu, T. (2006). The ‘Pasifika Umbrella’ and quality teaching: Understanding and responding to the diverse realities within. Waikato Journal of Education, 12, 35–50.

Sanga, K., Fa’avae, D., & Reynolds, M. (2023). Living well together as educators in our Oceanic ‘sea of islands’: Epistemology and ontology of comparative education. In C. A. Torres, R. F. Arnove, & L. I. Misiaszek (Eds.), Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local (pp. 433–454). Rowman and Littlefield.

Sauni, S. L. (2011). Samoan research methodology: The Ula-A new paradigm. Pacific–Asian Education Journal, 23(2), 53–64.

Siope, A. (2011). The schooling experiences of Pasifika students [Report]. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 10–16. https:// doi.org/10.18296/set.0421

Smith, H., & Wolfgramm-Foliaki, E. (2021). ‘We don’t talk enough’: Voices from a Māori and Pasifika lead research fellowship in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(1), 35–48.

Spiller, L. T. (2012). “How can we teach them when they won’t listen?” How teacher beliefs about Pasifika values and Pasifika ways of learning affect student behaviour and achievement [Report]. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 58–66. https://doi. org/10.18296/set.0393

Surtees, N., Taleni, L., Ismail, R., Rarere-Briggs, B., & Stark, R. (2021). Sailiga tomai ma malamalama’aga fa’a-Pasifika—Seeking

Pasifika knowledge to support student learning: Reflections on cultural values following an educational journey to Samoa. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56, 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-021-00210-7

Thornberg, R. (2012). Informed grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(3), 243–259.

Toumu’a, R. (2014). Pasifika success as Pasifika: Pasifika conceptualisations of literacy for success as Pasifika in Aotearoa New Zealand. http://repository.usp.ac.fj/7689/1/ACE_Aotearoa_report.pdf

Tuagalu, I. (2023). The energetics of vā and the Samoan faletele. In A.-C. Engels-Schwarzpaul, L. Lopesi, & A. Refiti (Eds.), Pacific spaces: Translations and transmutations (pp. 37–53). Berhahn Books.

Vaai, U., & Nabobo-Baba, U. (2017). Introduction: Paddling a relational renaissance. In U. L. Vaai & U. Nabobo-Baba (Eds.), The relational self (pp. 1–24). University of the South Pacific & The Pacific Theological College, Suva, Fiji.

Vaioleti, T. (2013). Talanoa: Differentiating the talanoa research methodology from phenomenology, narrative, kaupapa Māori and feminist methodologies. Te Reo, 56, 191–212.

Vuni, M., & Leach, G. (2022). Supporting Pasifika students in mathematics learning. Paper presented at the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia Conference, Launceston, Australia. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED623902.pdf