Overview

The project was a 2-year research-practice partnership between Aaron Wilson and Selena Meiklejohn-Whiu from Waipapa Taumata Rau | University of Auckland, Kiri Kirkpatrick and Naomi Rosedale from the Manaiakalani research team, and a group of Years 7 and 8 teachers from schools serving diverse communities throughout Aotearoa New Zealand. The schools represented in the study were demographically and geographically diverse and served urban, mixed, and rural communities in the North and South Islands. The university research team supported the teachers to plan and implement six T-Shaped Literacy units over 2 years. In each unit, students read multiple written, visual, oral, and multi-modal texts to explore one “big idea” in literature, such as how different writers use language to evoke mood and atmosphere, or craft a “great beginning” to a story, or create memorable characters. In each unit, students would learn about language and literary techniques, read texts, talk about texts, compare texts, and create their own texts, drawing on what they had learnt from the authors they had read.

Our project focused on the English learning area of The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) (Ministry of Education, 2007a) and aimed to develop Years 7 and 8 students’ metalinguistic knowledge, literary analysis (close reading), and creative writing. Over 2 years, the researchers supported teachers to support their students to explore six key literary ideas using text sets in an approach we call the T-Shaped Literacy Model (Wilson & Jesson, 2019; Wilson et al., 2024). The six topics were: mood and atmosphere; characterisation; narrative reliability; narrative structure; representation; and genre. We investigated the effects of the intervention on student learning using a quasi-experimental design with a range of repeated measures including measures of students’ knowledge of language features and literary elements, close reading of previously unseen literary texts, creative writing, and standardised measures of reading comprehension (PAT) and writing (e-asTTle).

The T-Shaped approach we took to teaching literary aspects of the English learning area differed from our teacher partners’ previous practice in two main ways. Firstly, the topics, while likely familiar to secondary school English teachers, were not as well known by the intermediate years’ teachers in our project. These were generally not aspects of literature that the teachers had taught, at least not in the depth and with the level of focus on technical language that they did in this project. This is not surprising given that our Years 7 and 8 teachers are generalists who, unlike most secondary English teachers, teach across most or all of the eight learning areas of NZC, and had not majored in English at university.

Our use of text sets to explore each literary aspect was the second main point of difference. It is more common in New Zealand English classes to organise a unit of work around a single text and to explore a wide range of its literary aspects. For example, in a unit centred on a novel, students would likely learn about its plot, themes, characters, characterisation, character development, conflicts, setting, narration, style, symbolism, structure, genre, and so forth. It is far less common, in our experience, for teachers to drill down and focus on one of these aspects in the context of multiple texts.

The term “T-shape” is an attempt to capture an approach that is at once deep and wide and narrow. The term was used originally in the field of job recruitment to describe the abilities of people in the workforce. The vertical bar on the “T” represents the depth of expertise in a specialised field, whereas the horizontal bar represents the ability to collaborate across disciplines. In our model, the horizontal bar represents the wide reading of multiple related texts whereas the vertical bar represents deep close reading and dialogue focused on important and specific aspects of the texts. The model is aimed to capitalise on the benefits of both wide reading and reading deeply and to resolve a potential tension between these. The potential tension is that too much focus on reading any single text deeply may limit the number of texts that can be read; on the other hand, too much focus on reading widely may reduce students’ opportunities to explore any one text or idea in real depth. The central proposition of the T-Shaped Literacy Model is that reading widely and reading deeply are both vital—and that it is possible to include both in a literacy programme so long as an important but relatively narrow focus is taken.

To illustrate, in our first unit, students analysed a wide range of texts with the important but narrow aim of exploring how different authors use language to create mood and atmosphere. Although other aspects of the texts, such as plot, character, and theme, were also addressed, they were largely discussed in terms of how they related to the main focus of mood and atmosphere. Texts were selected because they did a good (and sometimes, bad!) job of evoking mood and atmosphere. The texts in the text set included extracts from longer literary texts, short stories, poems and visual texts (picture books, film), and multi-modal texts. Students were explicitly taught how authors use language features to evoke mood and atmosphere; they analysed individual texts using appropriate metalanguage, compared and contrasted different approaches to achieve different effects, presented their analyses of a self-selected text to peers in the form of digital learning objects, and applied what they had learnt from their close reading when writing their own moody and atmospheric stories.

Teachers included a group of case study teachers—Danni Thompson, Lyndall Prendergast, Robyn Anderson, and Rochelle Clark. The Manaiakalani Programme[1] uses digital technologies to deliver “visible, learner centric learning and de-mystifying education for those learners so that they can stand alongside others as equals in knowledge building in school, in their communities and in wider society”.

Why this study was important

The project aimed to prepare students for some of the ways in which literacy becomes, or should become, more complex as students advance through their schooling years. One such progression is in disciplinary literacy in which the texts associated with different learning areas become much more specialised, as do the purposes for reading and writing them, and the skills and knowledge needed to achieve those purposes. In subject English, students are increasingly expected not just to comprehend texts but to appreciate how authors craft literary texts to achieve particular effects (Lee & Spratley, 2010). This is a step up to a more specialised form of reading. By Years 7 and 8, students are already expected to be able to demonstrate a “developing” (Curriculum Level 3) and “increasing” (Curriculum Level 4) understanding of how “texts are constructed for a range of purposes, audiences and situations”, how “texts can position a reader”, and how “language features are used for effect within and across texts” (Ministry of Education, 2007b). Being able to analyse and appreciate how authors use language to achieve effects, including literary effects, and knowing how to achieve these effects in their own writing, are highly valued outcomes in subject English. Knowing how texts “work” is powerful knowledge well beyond subject English because it allows all readers to identify when and how authors are using language to position and influence them and, therefore, to make more critical and informed decisions about whether to accept or resist that positioning.

National and local evidence, however, point to issues in student achievement and upper primary teacher knowledge. A recent round of the National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (NMSSA) showed that many students were able to make inferences, predictions, hypotheses, and evaluations about texts they read but struggled to support their view with specific references or evidence (NMSSA, 2021a). Year 8 students nationally had limited knowledge of language and design features of texts (e.g., figurative language, visual semiotics), seldom used appropriate meta-language, and struggled to explain how authors create effects (NMSSA, 2021b). These patterns are consistent with data from The Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLs) where students’ ability to read literary texts is assessed in terms of their locating and identifying significant actions and details embedded across the text; making inferences about relationships between intentions, actions, events, and feelings; interpreting and integrating story events to give reasons for character actions and feelings traits and feelings as they develop across the text; and recognising the use of some figurative language (e.g., metaphor, imagery). Despite New Zealand students on average still achieving well by international standards in PIRLS, we have a higher proportion of students achieving in the lowest bands, persistently inequitable outcomes for children from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds, and a decline in performance over time (e.g., Hood & Hughson, 2022; Johnston, 2023).

There is limited empirical evidence about actual patterns of subject English teaching in upper primary New Zealand classrooms. Previous research we conducted with the wider cluster of schools showed that, while children had opportunities to learn about literacy in general, they had fewer opportunities to learn about subject English. We had collected online data from 155 class sites and analysed all 576 texts and 536 activities provided to students over a 1-week period. Most (67%) texts used in reading lessons were informational rather than literary texts and very few (6%) were extended written texts such as chapter books. While most (56%) had some focus on vocabulary development, fewer than 25% mentioned any literary elements (such as theme, setting, characterisation) at least once, and only 13% showed evidence of a focus on literary devices.

Using text sets to develop literary knowledge

Most accounts of text sets in literacy programmes focus on the use of thematically connected texts (Reynolds, 2022) but the thread that connected the texts in each set that teachers curated was related to the crafting rather than the topic of the text. Our aim was not just to support students to understand the features of the text at hand, but to develop transferable knowledge that can be applied to other texts in the future. The literature about transfer suggests that revisiting the same concepts in different instantiations supports transfer, presumably because repeated exposure enables students to see the deep underlying principle that connects those instantiations, rather than the surface differences between them (Bransford et al., 2000).

In designing our approach, we sought to capitalise on the affordances of the wider digital learning programme. Students in schools like these have a wider range of digital mediums to draw on for showing and sharing their understanding of the text(s) (Rosedale et al., 2021). Digital learning objects (DLOs) are multimodal re-representations of knowledge that use “new” media such as screencast, podcast, and animation. Student creation of DLOs can deepen thinking and learning using a process of transduction whereby content is transformed from one modal representation into another (Bezemer & Kress, 2008). Re-presenting a moody setting from a short story in a film clip is an example of transduction that requires students to understand both how written language features, such as sensory imagery, AND visual language features, such as colour and lighting, evoke mood. In our project, students selected their own texts for analysis and created and shared their close readings with their peers in the form of screencast videos and presentations.

Research questions

The overarching research question was: What are the effects of the T-Shaped Literacy Model on Years 7 and 8 students’ disciplinary reading and writing in subject English?

Sub-questions are:

- To what extent is co-design and implementation of a T-Shaped Literacy intervention in subject English associated with accelerated progress of Years 7 and 8 students in disciplinary (near transfer) and standardised (far transfer) measures of reading and writing?

- What factors act as barriers and enablers for the implementation of T-Shaped Literacy in English by teachers and students?

Method

To answer the research questions, the study had quantitative and qualitative strands. The quantitative strand used a quasi-experimental design with repeated measures in Term 1 and Term 4 of 2022 and 2023 (RQ1). The comparison group was composed of students from other Manaiakalani schools with similar demographics to the project schools and who received business as usual literacy instruction. The qualitative strand (RQ2) involved thematic analysis of focus group interviews with teachers and students, teachers’ class sites (units of work they developed), and samples of student work.

We partnered with volunteer schools within the Manaiakalani network. In the first year of the project, we partnered with 22 teachers from 12 schools within eight geographically based clusters across the North and South Islands. In the second year, the project worked alongside nine teachers in six schools from six different Manaiakalani clusters. Data from all students who competed assessments at the beginning and end of each year were included in our analysis.

Measures

Student learning measures

Researcher-designed measures

We developed measures of students’ knowledge of language and literary features, close reading, and creative writing. Content validity of the items for the different measures was checked with two independent national experts in secondary English. All scripts were blinded so the marker did not know which school the student came from or whether it was from the beginning or end of the school year. Moderation checks were completed to establish reliability of marking.

- Knowledge of language features. This was a multi-choice test that required students to identify parts of speech (e.g., adverbs, concrete nouns) and figurative devices (e.g., personification, simile) in sentences.

- Close reading assessment. This was an open response format that involved independent close reading of an extract from a literary text from levelled School Journals. Students were instructed to: “Explain three ways that the author used language features to make you feel strongly about people, places, or ideas.” A researcher used the marking rubric to mark the open-response portions of the test. Assessments were marked blinded, meaning the scorer could not tell if the text was written pre or post the intervention.

- Constrained creative writing activity. Students were able to write whatever they chose in response to the following instructions: “Describe a character using language in ways that show your reader that he/she is an unlikeable character. Your character might be imaginary or based on a real person.” It was marked using the same approach as the close reading assessment above.

- Knowledge of literary terms. This was a multi-choice format test used at the end of the project to assess students’ knowledge of literary terms such as dynamic, static, flat, and rounded characters.

Standardised measures

The achievement and progress of students who participated in the project was compared to national norms. The standardised assessment tools used were:

- PAT Reading Comprehension (now replaced by the refreshed PAT Pānui | PAT Reading Comprehension https://www.nzcer.org.nz/assessments/pats/panui-reading)

- e-asTTle Writing (http://e-asttle.tki.org.nz/Teacher-resources/e-asTTle-writingBackground). Both are online standardised assessment tools used by all schools in the wider project at the beginning and end of each school year. The standardised tests are far transfer measures in that they are framed around broader constructs of reading and writing than those addressed in the intervention.

Quantitative analysis

Paired t-tests were applied to pre score and post score for both academic years (2022 and 2023) to investigate whether T-shape training was associated with significant improvements from pretest to post test. P-value and effect size (Cohen’s d) were also given. We were not able to match individual comparison group students from pre to post in 2022 so were only able to conduct treatment versus comparison group comparisons in 2023. In 2023, a two sample t-test (Welch test) was applied to treatment group improvement (post-pre) and comparison group improvement (post-pre). P-value and effect size (Cohen’s d for Welch test) were also given.

For “Knowledge of literary metalanguage” (2023 single time point post intervention), a two sample t-test (Welch test) was applied to treatment group post score and comparison group post score.

The standardised assessments have different norms for the beginning and end of each year level. To create a common scale for students of different year levels, and to control for normal growth, we calculated a “normdiff” score for each student by subtracting their actual score from the national norm at each time point. A student with a normdiff score of zero, regardless of their year level, achieved at exactly the same level as the national norm for that age group. Negative integers indicate their scores were below norm and positive integers that they were above. Change in achievement was explored using paired-samples t-tests for all students who had test scores for both time points.

For PAT reading and e-asTTle writing, paired t-test was applied to normdiff1 (normdiff at term 1) and normdiff4 (normdiff at term 4) for both 2022 and 2023 treatment groups (selected treatment schools). P-value and effect size (Cohen’s d) were given. The results can tell us whether the treatment groups students achieved better improvement than national level from term 1 to term 4 in each academic year.

We were also interested in finding out if the programme had an associated “dosage” effect so we applied a two sample t-test (Welch test) to compare end of 2023 scores of those Year 8 students who took part for 2 years (2022–23) and 1 year (2023 only).

Qualitative analysis

Teacher focus group interviews were conducted with co-design teachers immediately before and after the intervention in 2022 and 2023 to investigate their perceptions of the principles, purposes, benefits, drawbacks, barriers, and enablers of T-Shaped Literacy (RQ5). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analysed thematically.

Professional learning and development (PLD)

Participating teachers worked as co-designers in a research-practice partnership with the University of Auckland and Manaiakalani research teams to learn about, co-design, and implement three units of work per year. Teachers were supported to plan and implement the six units in a series of online after-school PLD sessions of about 1½ hours each. The number of sessions we held for each unit progressively reduced. We held four sessions to support the first unit on Mood and Atmosphere because teachers needed more input and support coming to terms with the model, the aims, the concept of close reading, and the different activities and approaches such as DLO development and dialogic talk. Because these activities and approaches were repeated multiple times, teachers found they needed less support over time. Time allocated to PLD sessions was responsive to additional workload many of the teachers had. Some teachers were senior leaders, middle leaders, and one a principal, all working very hard to offer the best literacy opportunities for their students. By the later units, we focused most of the time on developing teachers’ knowledge of the key concepts that would be developed in the unit, the key language and structural features, and their associated meta-language. Support from the researchers from each unit included providing: a set of specific learning outcomes, including key terms and concepts students would learn; materials teachers could use or adapt to explicitly teach terms and concepts; modelling close reading with exemplar texts to help teachers learn how to apply new knowledge to actual texts; and suggestions about possible texts that might be included in their text sets. The sessions were divided fairly evenly between researcher-led content and activities, and opportunities for teachers to discuss and share their own ideas.

T-Shaped Literacy—2-year programme

The researchers and teachers co-designed six T-Shaped Literacy close reading units over the course of 2 years: Mood and Atmosphere; Characterisation; Narration; Great Beginnings; Representation; and Genre. Units typically lasted between 3 and 5 weeks each. We developed a unit overview and supporting materials for each of the six units. Teachers were able to choose to adapt the unit overview to suit themselves and their children.

One outcome of the project was an agreed framework for unit planning. Some aspects of the unit framework, such as having an engaging beginning, were already commonly used by the teachers but we felt it important not to leave these important aspects to chance. Other aspects, such as the number and features of texts in a text set, were specific to this project. The amount of explicit direction and support we gave teachers evolved over the 2 years. By the beginning of the second year, we had established an agreed expectation that each T-Shaped Literacy unit would include:

- an engaging beginning that introduces the focus, why it is important, and gives an overview of the key learning outcomes and summative activities students will be working towards

- explicit teaching to develop linguistic and literary knowledge and processes for close reading, synthesis, and creative writing

- texts selected because they are good (and sometimes, deliberately bad!) examples of the literary focus. Texts will often be shorter extracts from longer texts. Text sets would include a balance of mirror and window texts, and scaffolding, complementary, tension, and student-selected texts. Mirror texts are those with familiar settings and characters and so forth that students “can see themselves in” whereas window texts open up views into unfamiliar worlds

- activities that support close reading of at least THREE written and TWO visual, oral, or multi-modal texts.

Close reading activities

Close reading activities for each text in the text set were to include:

- preparing to read activities that create purpose and interest and activate and build background word and world knowledge

- student “eyes on text” reading time

- opportunities for open-ended discussion about students’ affective response to the text, and its audience, purpose, ideas, and language

- support for students to notice and think about how language is used to create literary effects and develop their critical literacy. This includes explicit teaching and reinforcement of language features important to the literary focus and which were powerful in that text

- strategy development through explicit teaching and modelling of strategies as well as opportunities for students to reflect on and discuss processes, problems, and problem-solving strategies

- support to record information about that text that can be used for the synthesis activity later in the unit

- support for “magpie-ing” interesting words and phrases from the text that they can use in the creative writing task later in the unit

- an opportunity to use/practise new knowledge about language and that text in a short piece of creative writing.

Summative activities for each unit

Towards the end of each unit, students were expected to complete three overall tasks that would bring all their new learning together. They would create and share:

- a Digital Learning Object: Students select their own text/extract for close reading and create a digital learning object to develop peers’ knowledge of the topic and that text

- an original piece of creative writing: Students use the knowledge of language they have developed through close reading in their own creative writing

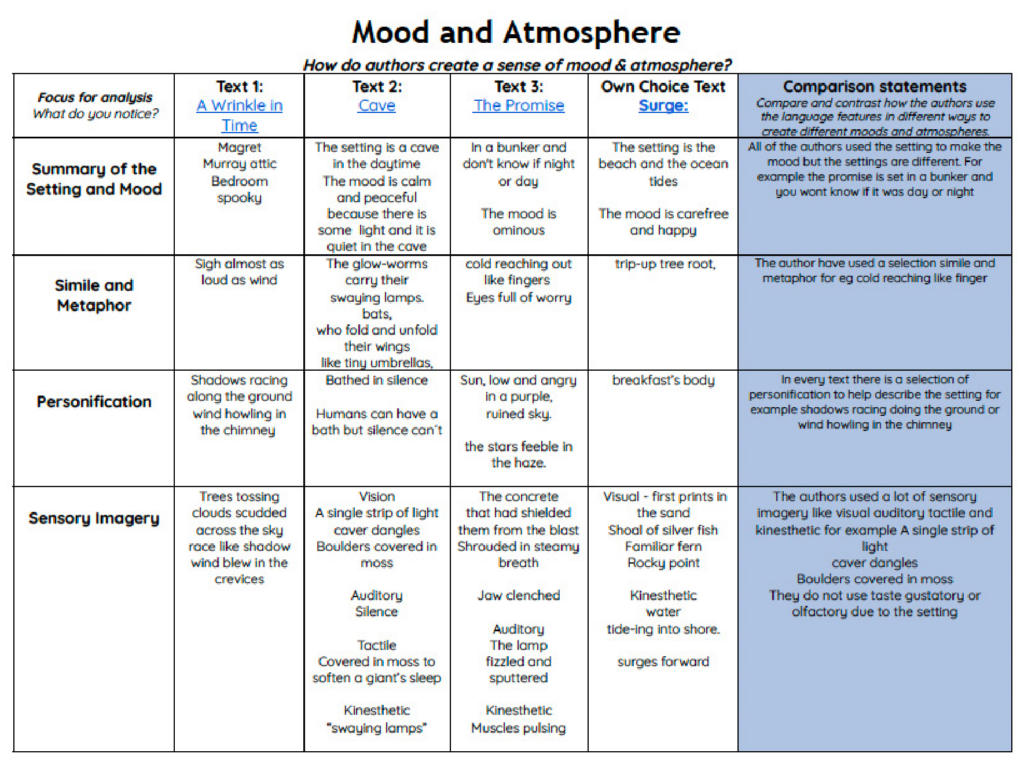

- a synthesis activity that compares and contrasts how language was used to achieve the literary purpose in different texts. Teachers most commonly supported students’ synthesis with tables similar to this one that Lyndall, a teacher from Grey Main, used in the Mood and Atmosphere unit. This is an extract from a larger synthesis table completed by Ariki, a student from Grey Main:

Summary of the six T-Shaped Literacy units

A brief overview of the six units that comprised the 2-year T-Shaped Literary curriculum for Years 7 and 8 students follows. We provide examples of materials teachers developed to give a flavour of what was produced.

T-Shaped Literacy units summary and key concepts table

| Unit title | Overview |

| 1. Mood and Atmosphere | How authors use language to evoke a strong sense of mood and atmosphere. Key content/terminology included: setting, sensory imagery, figurative language, modifiers, word choices. |

| 2. Characterisation and Character Development | How authors create a strong sense of character. Key content included: character types, antagonist, protagonist, flat character, round character, static character, dynamic character, internal and external conflict. |

| 3. Narrative Point of View | A particular focus on unreliable narrators and whether any narrator is really reliable. Key concepts included: point of view, types of narration and their effects on readers. |

| 4. Great Beginnings | How authors engage readers at the beginning of texts. Key concepts/terminology included: three-act story structure, orientation, exposition. |

| 5. Representation | Exploring patterns in how a group of people are represented across multiple texts. Key concepts/terms included: critical literacy, power, status, representation, stereotype, counterstory telling. |

| 6. Genre | Understanding that there are different literary genre that use particular conventions and tropes. Exploring the conventions and tropes of one genre. |

Mood and Atmosphere

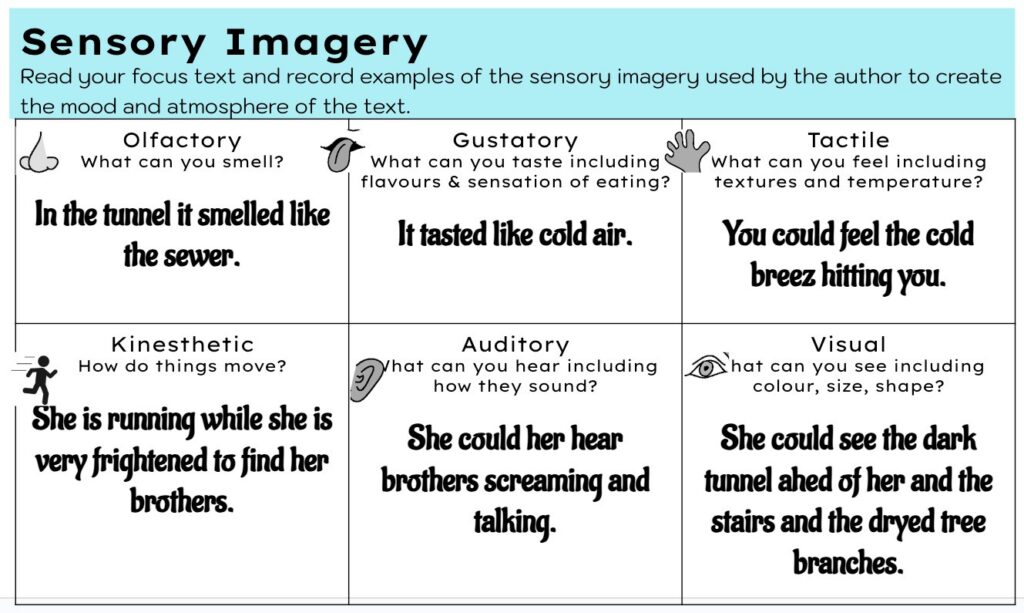

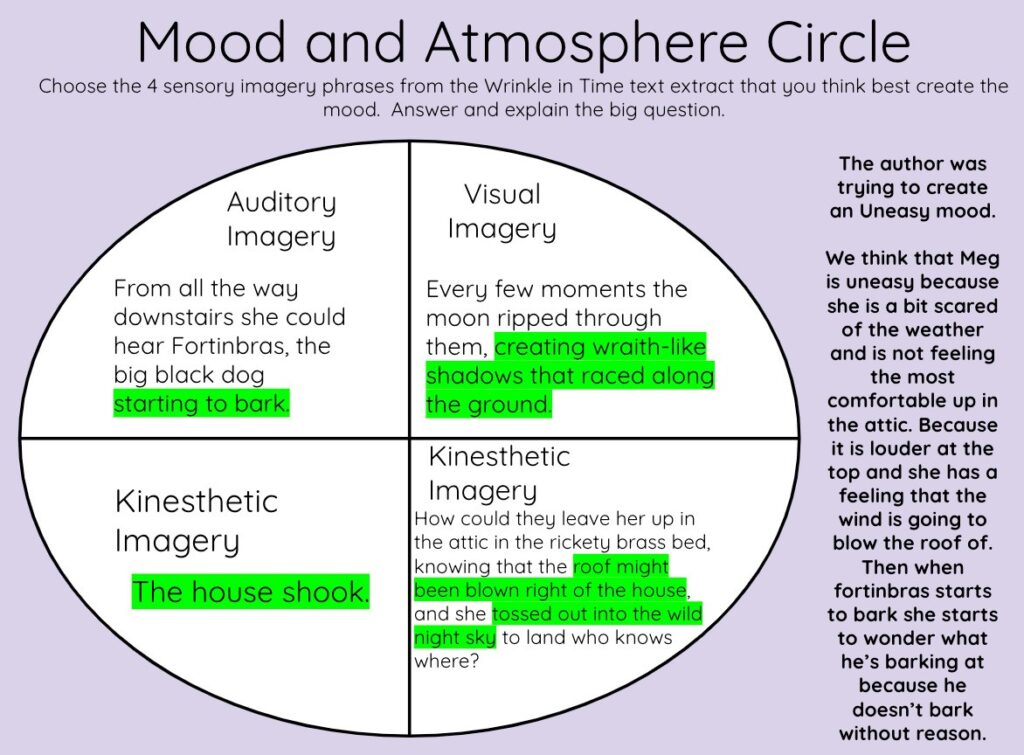

The focus of the Mood and Atmosphere unit was on developing students’ understanding of how authors use language features to engender mood and atmosphere in their readers and how they, as writers, could then use these language features in their own creative writing. Key language features and their associated terms that we focused on included sensory imagery (e.g., visual, aural, gustatory, olfactory, tactile), parts of speech (e.g., concrete nouns, verbs, adverbs, adjectives), figurative language (e.g., metaphor, simile, personification), and choice of words (especially the connotations of words).

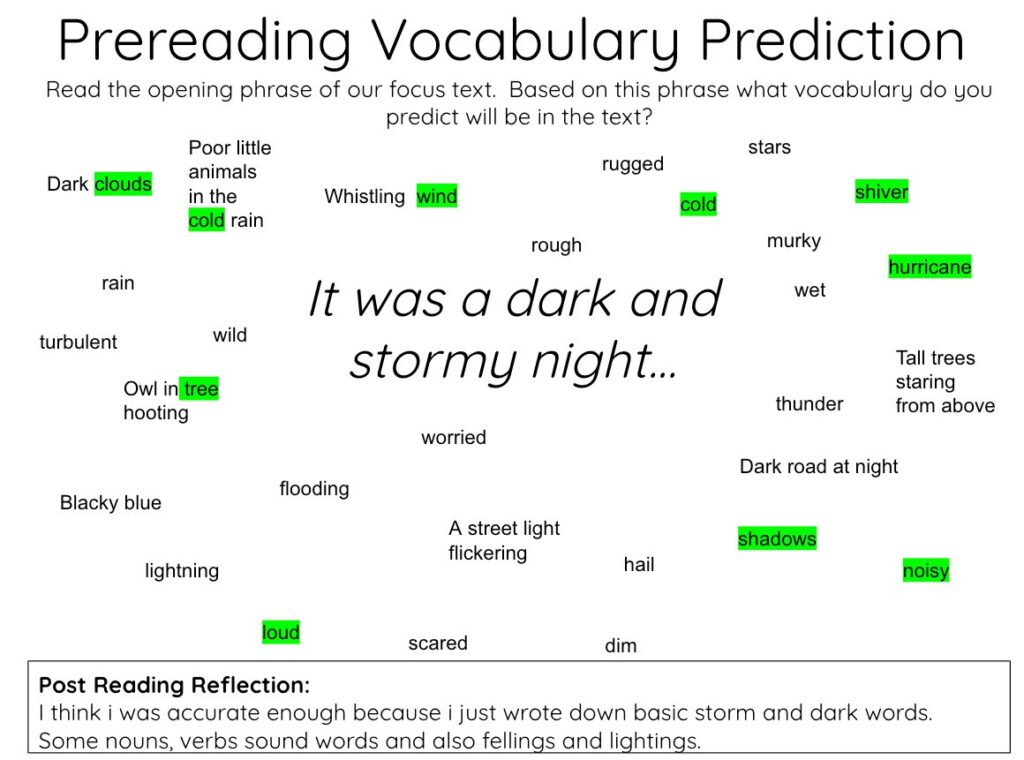

Lyndall designed the following activity as part of her Mood and Atmosphere unit. Students were given an opening phrase for a text they were going to read (“It was a dark and stormy night …”) and brainstormed words and details they predicted might be in that text. After reading, they went back and highlighted words that were in fact in the text. Here is an example completed by Noah at Grey Main:

Later in the unit, Lyndall explicitly taught her students about the different types of sensory imagery and about how to identify and explain the effects of sensory imagery in the texts they studied.

In the earlier texts in the unit, students were provided with a higher level of scaffolding. In this example, Anahita from Grey Main was given a template that provided visual and written definitions of the technical terminology:

Later in the unit, students were expected to analyse the use of sensory imagery in the texts with a reduced level of scaffolding. Here is one group’s analysis of sensory imagery in the text Wrinkle in Time:

One of the key summative activities was for students to apply what they had learnt from their close reading to their own creative writing.

Here is a published piece of writing by Mikayla from Grey Main where she applies what she had learnt about creating a strong sense of place, mood, and atmosphere particularly through her use of sensory imagery, well-chosen verbs and adverbs, and figurative language devices including simile:

Characterisation

This unit focused on key concepts and terminology related to character, characterisation, and character development. Students were supported to describe characters from each of the texts they read in the unit using terms such as “protagonist” and “antagonist”, “dynamic” and “static, and “round” and “flat”. They were also introduced to terms related to character archetypes (“hero”, “nemesis”, “mentor”, “ally”), and to the concepts of internal and external conflict. Key language features that we explored included authors’ use of proper nouns (e.g., exploring the connotations of characters’ names), action verbs and adverbs used to describe characters’ movements and actions, concrete nouns used to describe places and objects associated with that character, adjectives, figurative language, dialogue (especially how characters speak), intertextuality (characters who have echoes of another character in another text), and animal imagery.

Narration

The focus of this unit was on the concept of unreliable narrator, different ways a narrator might be more or less reliable, and whether any narrator should ever be regarded as being completely reliable. Students learnt about narrative Point of View (POV) and how to identify the three main forms of narration (first, second, and third person). They experimented with rewriting texts in different forms (e.g., rewriting a first-person narration in the third person, rewriting a third-person narration from the POV of a different character), and discussed the effects of these changes on them as a reader.

The following screenshots show an example of how the same analysis activity was used by Robyn in relation to different texts: Voices in the Park by Anthony Browne and Bok Choy by Paul Mason.

An affordance of this example for teachers is that the planning load is reduced because the same activity can be recycled. An affordance for students is that they have the opportunity for repeated practice and reinforcement.

Great Beginnings

In this unit, students studied the beginnings of a range of texts and for each text they considered the extent to which it was a “great beginning”. The overall aspect they considered was whether and how the beginning made them want to read on, and how well the text did jobs such as introducing the setting, establishing tone, creating empathy for a protagonist, creating expectations. and introducing a conflict or goal or problem to be solved.

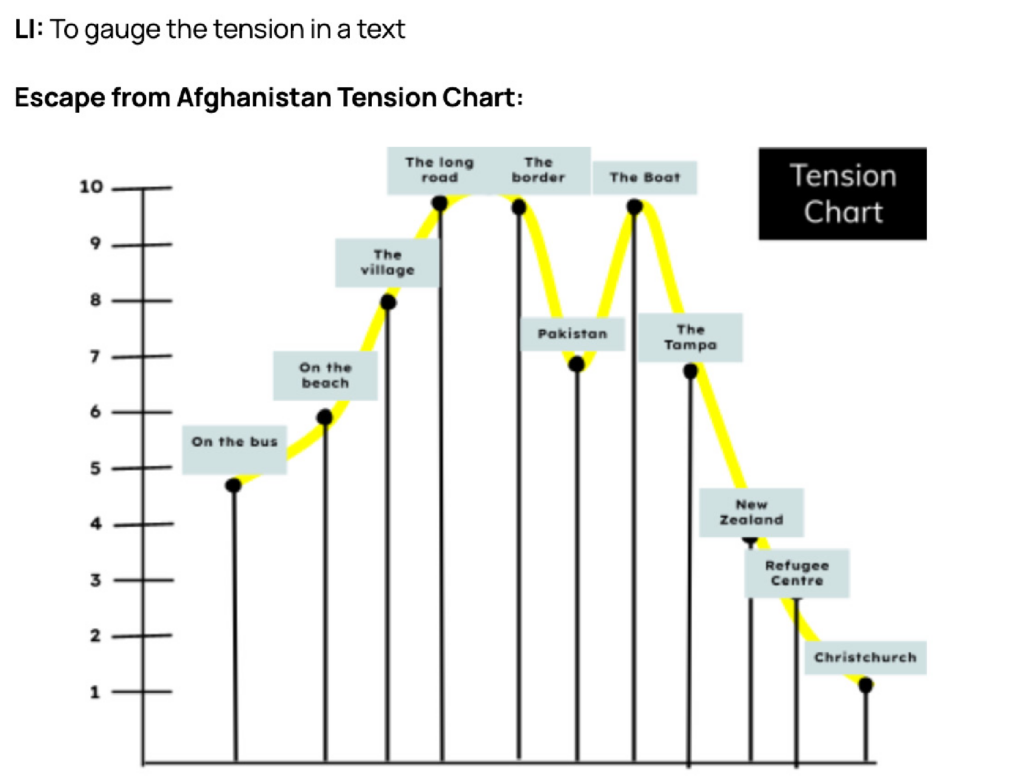

Students were taught about the three-act structure and terms associated with that structure including exposition, inciting incident, dramatic question, dramatic tension, rising action, resolution, and climax. Links were made to previous units to explore aspects of exposition in the first act and reinforcing terminology such as introduction of setting and character, establishing time and empathy for a character, signalling tone, conflict, and foreshadowing.

Here is an example of a scaffolded digital artefact by a group from Panmure Bridge School where they mapped the rise and fall of tension across the text Escape from Afghanistan:

Representation

This unit had an explicit critical literacy focus. Students explored how different ideas or groups of people are represented in texts. They were introduced to the idea that neither authors nor their texts are neutral and that, incidentally or deliberately, authors represent different groups of people in different ways. We modelled a unit exploring representations of older adults in various media and suggested that teachers explore representations of a particular group or two or more contrasting groups. Topics teachers explored with their classes included representations of gender for sportspeople and superheroes. We had a strong focus on what teachers could do to keep all children safe as they explored potentially sensitive issues and built awareness that a teaching focus aimed at surfacing stereotypical representations of a group can have the unintended consequence of reinforcing stereotypes. We explored how authors of visual and written texts position characters as more or less powerful; for example, through high versus low camera angles and use of first person singular (I) versus first person plural (we) versus second person (you) versus third person plural (them).

Genre

In this unit, students were introduced to the idea of genre and how different genres of literature, music, and film have associated with them particular tropes, themes, topics, settings, characters, and key events. Classes selected a particular genre and analysed texts in order to identify genre features and to create an original text in that genre.

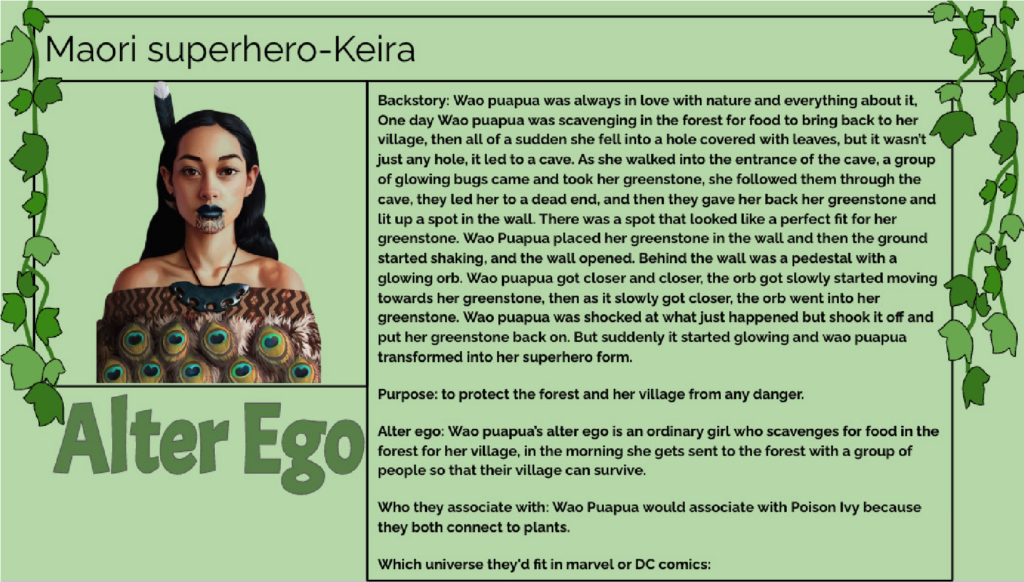

Students at Panmure Bridge School studied genre conventions of superhero texts from the Marvel and DC universes and created their own superheroes. Here are samples of work developed by Keira and Riley:

Results of quantitative analyses

In this section, we summarise data about shifts in student achievement associated with the project. Tables presenting our quantitative analyses are included in the appendices. Analyses of student data for the repeated researcher-designed measures (Table 1 in the Appendix) showed that students in the project made statistically significant improvements in their scores for language features (Effect size = .59) and close reading (ES = .40) in 2022 and for language features (ES = .61), close reading (ES = .53) and creative writing (ES = .29) in 2023.

Furthermore, the gains that students in T-Shaped Literacy classes made in all three areas were significantly more than students in the comparison group who received their normal English programme (Table 2). The effect size of the difference in the gain of project students and comparison group students was .61 for language features, .48 for close reading, and .37 for creative writing.

Treatment students at the end of 2023 had significantly higher scores for knowledge of literary metalanguage than comparison group students (ES = .59) (Table 3).

Standardised measures

Despite making significant gains in the more specialised measures related to close reading, students did not make accelerated gains (relative to national norms) in the more general standardised measure of reading comprehension (Table 4). Overall, gains for treatment students were not significantly different from gains for students in the norming sample in 2022 and were significantly lower in 2023. It is important to note that the pattern of students in the cluster of schools making lower-than-norm progress in PAT reading is a longstanding one.

Overall, students in the project made accelerated gains in the standardised measure of writing with an effect size compared to the national norm of .26 in 2022 and .31 in 2023 (Table 5 in the Appendix).

Analyses of “dosage”

The following “dosage” analyses were conducted to see if the end-of-year scores were higher for Year 8 students who took part in the project for 2 years than those who took part for only one of the years. The effect sizes of the difference in gain for Year 8 students who took part in the project for 2 years (i.e., Years 7 and 8) versus those that took part for 1 year were .74 for language features, 1.16 for close reading, and .97 for creative writing (Table 6). There was no significant difference for PAT Reading (Table 7) but there was a significant positive dosage effect in e-asTTle writing (ES = .58) (Table 8) and for students’ knowledge of literary features (Table 9).

Results of qualitative analyses: Student and teacher voice

In this section, we report analyses of our interviews with teachers and students. The purpose of the interviews was to gain a more nuanced understanding of teachers’ and students’ experiences of the project and, in particular, to answer the second research question about factors that acted as barriers and enablers.

Teachers reported that students enjoyed the T-Shaped units and were proud of the work they completed. Students in the focus groups echoed this belief and were clearly keen to show us the learning they had developed in the units, peppering their responses with ideas and technical language they had learnt in the programme:

- “Now in T-Shape literacy we have to like find out what (type of) character they are. For example, the protagonist or antagonist and all the different rules like static and dynamic. The static character is when they stay the same throughout the story, dynamic character is when they change and develop throughout the story.”

- “The representation (was the most interesting unit) in my opinion because in that we did about superheroes about gender bias which talks about why male superheroes are more shown into movies, comics and cartoons than females and it says that 27.5%, I think, women is shown (as a main character at all) and only 12% is the main protagonists.”

- “I think my proudest writing would be comparing the (book covers of) two texts Goosebumps and My Family Divided because we used colour symbolism and our visual senses to see what genre this is, what type of colour they made it to this genre, the font style and the hue.”

- “One of the things I like in the T-Shape literacy learning was the mood and atmosphere where it taught me about more words about the sensory imagery and some of the words that we learnt was auditory, visual, tactile and olfactory and kinaesthetic.”

Teachers felt that the level of challenge within the units was high for students, but achievable:

- “The work that you guys shared with me, and then I used was really high level and it pushed the kids.”

- “I think [the content] is much more advanced.”

- “The concepts have been challenging for many of my learners.”

They also felt that the content about literary and language aspects of the English learning area was new and challenging learning for them as teachers:

- “I have not really spent this level of time exploring genre before.”

- “T-shaped literacy has opened my eyes.”

- “I feel I have a much better understanding (of the topics) myself.”

- “The materials have been invaluable for understanding the concepts needed to teach.”

Teachers felt that students were more focused on “deep” learning within the T-Shape Literacy units:

- “Finally, a critical analysis that was more than just name dropping with no change to practice.”

- “[Students can] unpack texts in an in-depth way rather than just surface.”

- “T-Shaped literacy is the only literacy program I have worked with that centres on learning at a deep level.”

Students also felt that the work they did allowed them to go “deeper” than they had previously and spoke positively about the challenging work they engaged in:

- “I used to watch movies. I (would) always think of it like ‘a movie it is not going to help me with anything’, but ever since T-Shape literacy I could like dig deeper into the movie and to see who was the protagonist and the antagonist and static and I could describe the scene whenever I’m watching a movie.”

- “(My advice to a new teacher would be) tell them to give the students hard out and more complex words so it could help their students to expand their vocabulary list.”

Teachers identified student motivation as an important outcome from their work with students and attributed this most often to the pride students got through doing more challenging learning:

- “A feeling of empowerment and success at a higher level has been the biggest catalyst in motivating students.”

- “The motivation really built for the kids when they saw what they could produce after doing the learning.”

Another motivating factor for students that teachers identified was the increased collaboration:

- “(Students are more engaged because) everyone feels like they’re a part of it.”

Students also saw increased discussion and collaboration as the biggest change they experienced moving into the T-Shaped approach:

- “I feel like there is more collaboration in T-Shape and everyone is able to share their own opinion … being able to share your own opinion and not like being judged for it.”

- “We think that collaborating with others just to share makes people share ideas and to see different points of view on what is this and what is that.”

- “We explore in extended discussions, so where we see each other’s opinions and what ideas we would like to share with each other.”

The teachers often emphasised vocabulary as a particularly valued element of the T-Shaped units:

- “The focus on vocabulary … was a game changer for us.”

- “I found that the biggest win with the kids was building that really strong vocab.”

- “More technical literary language has benefited my students.”

Vocabulary was also the learning outcome most commonly identified by the students:

- “It also helped me with my vocabulary, being able to learn new words and seeing them in texts like I can go confidently … I know what the meaning is.”

- “I will feel very confident going to college English because I learnt a lot about vocabulary and words like I never knew before and using them in college will help.”

Teachers and students also identified how the close reading activities supported the students’ own creative writing:

- “I think the Great Beginnings one is my favourite because if I was to write a story, I would know how to pull people in.”

Teachers felt that the frameworks and examples presented in the PLD sessions were helpful:

- “[The] concrete examples that were provided enabled a clear understanding.”

- “You knew the big questions; you knew what you were trying to achieve.”

- “I can see clearly what needs to be covered.”

Teachers appreciated having models and practical examples presented in the sessions that they could use in their classrooms almost immediately after the sessions:

- “You could go away and try them and use them and then build on them and branch out.”

- “You had activities we could try and use and adapt straight away.”

On the other hand, though, it was clear that the teachers saw themselves as adaptive experts rather than simply implementers of pre-packaged approaches. They were clear that they wanted to tailor the lessons to their own classroom context:

- “It has been a fun and enjoyable unit that I have been able to tailor to my students and their context.”

- “You can customise it to your actual cohort of students.”

- “I have had to consider what to select that will appeal to my students and the learning needs of my students.”

Tailoring the units to their students’ interests and cultures was a particular focus for the teachers. Students appreciated teachers’ efforts in this respect and spoke positively about how the texts they read and wrote connected to their cultures. This was particularly true of students who learnt about conventions of the superhero genre and created their own superhero character:

- “I think I would share my superhero that I made because it shows my culture, and it also shows what I would want to be.”

- “I enjoyed creating my own superhero because like I got to use my own characteristics and my culture which you don’t really see very many Māori superheroes on TV or like shown and I got to give it my own unique features. So her name is Raupopo, she is a Māori superhero, she saves her little village from being attacked and she also protects the forest. Some of her weaknesses are forest fires and global warming. She has her superpowers in her greenstone that she got from a cave that she fell into and her normal greenstone opened a wall and some orb came and gave her the powers that she has.”

Teachers reported difficulty with attending regular meetings due to unplanned disruptions, conflicting meetings, and illness (especially with COVID in 2022) but appreciated that course materials were easily accessible and could be accessed in their own time:

- “The video recording provided me with rewindable opportunities if I needed them.”

- “The website is fantastic, and I used it often.”

Discussion

The quantitative data suggest that the programme was successful overall in developing students’ achievement in key aspects of the English learning area. Importantly, students who participated in the programme for 2 years (Years 7 and 8) ended their intermediate years with significantly higher scores than students who only participated for 1 year. We believe, therefore, that the evidence overall points to the programme being an engaging and effective component of a 2-year English curriculum for Years 7 and 8 students.

In addition, we believe there are features of our approach to teacher PLD that make our programme more scalable than some programmes. The total amount of formal time for teacher PLD was relatively light. The sessions were held after school and online. All of the sessions were recorded and were supplemented by other materials emailed and posted on the project website. This rewind-ability was invaluable, especially at the time of the project where COVID was rampant. We are currently producing a set of resources to support teachers to design and implement the programme. None of this is to suggest that implementing this approach, or taking it to scale, will be easy. We are in awe of the work and commitment the teachers demonstrated. There was a huge amount of professional learning for all the teachers in what was essentially a crash course in secondary English teaching for non-specialist intermediate teachers. There was then a huge amount of work curating text sets and planning activities that would engage their learners, and then implementing, reflecting on, and refining new approaches to teaching new content.

The only measure where students in the project did not make greater gains than other students was in PAT Reading Comprehension. As mentioned, the pattern of progress in PAT being at or slightly lower than the national norm is a longstanding problem in the cluster. It is possible that, despite being at or slightly lower than progress rates in the national norming data, they were still better for the students of participating teachers than previous cohorts. We are undertaking further analyses to see if this is the case. One possible reason why PAT Reading Comprehension proved more resistant to improvement is that the other measures were more tightly linked to the learning focus of the programme and were therefore more sensitive to change than the standardised measure which assesses a much broader construct of reading. The improvements we identified in knowledge of metalanguage and close reading did not necessarily show up in more global measures of reading. Ongoing revisions to the programme will focus on how we can better effect improvements in close reading AND in reading comprehension more generally. An implication of this result nationally is that we cannot assume that a strong English programme in and of itself will accelerate students’ achievement in global measures of reading comprehension, at least not in the short term and not for students who begin the programme with lower scores.

In our introduction to this report, we described how Aaron Wilson and Rebecca Jesson originally designed the T-Shape Model as an attempt to resolve a potential tension between reading widely and reading deeply. Looking back on our learning over the past 2 years, and the data we collected, we note several other potential tensions that we feel we managed to balance effectively as well.

One potential tension is in the balance of teacher autonomy and programme prescription. Discussions with teachers showed that they wanted more explicit guidance that would support the development of their content knowledge about the literary concepts and the metalanguage and the pedagogical knowledge they needed to plan teaching and learning opportunities for their students. We found that the teachers greatly appreciated having very specific guidance about which learning outcomes to focus on, such as what language features and literary ideas to include in the unit. We found that they also appreciated having a clear framework to guide their unit planning. Some commented that they had not planned units in such a deliberate way since their Teaching College years. On the other hand, we were, and remain, very wary of too much prescription. The schools represented in the study were demographically and geographically diverse and served urban, mixed, and rural communities in the North and South Islands. We aimed to achieve the delicate balance between giving them enough support to enable high-quality delivery of what was to most very new learning, and enough autonomy to respond to the diverse strengths, needs, and interests of the children in their classes. Consistent with this, the aim of the PLD sessions was to support teachers to select their own texts and plan their own learning activities. The student and teacher voice suggest to us that we were quite successful in achieving the balance of providing teachers with enough support and guidance about what and how to teach, without stifling their ability to find texts and plan activities that would engage and meet the learning needs of the children in their own classrooms.

Another balance we think we managed to strike was between explicit teaching and student-centred collaboration. There was a marked step up in the explicit teaching of language and literary features but there was also a marked step up in the levels of collaboration and discussion. These do not have to be seen as oppositional; rather, we believe the increased explicit teaching afforded the students with the conceptual and linguistic resources needed to engage in richer discussions. Similarly, we were pleased by the students commenting positively about the arguments they had in discussions about different texts because this suggests that more explicit teaching about how a writer used language to achieve a particular effect did not limit the interpretative space children had to offer a different reading.

Another potential tension was between analysis and creativity; we believe that the development of students’ knowledge and skills for literary analysis fostered rather than hindered their creativity. This was evident, for example, in the pride students took appropriating what they had learnt from expert writers in their own creative writing (which suggests the resolution of another potential tension, between reading and writing). Another tension, or false binary, was in the use of multimodal and written texts. We were committed to and were successful in increasing the amount of reading and writing students were doing. But at the same time, students’ knowledge of oral, visual, and multimodal text features increased as well. For example, students in the Mood and Atmosphere unit analysed the use of colour and lighting in film texts before studying how writers used visual imagery through written language.

Footnote

Waiapapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland research team

Principal investigator—Aaron Wilson is an Associate Professor in literacies education and Head of the School of Curriculum and Pedagogy in the Faculty of Education and Social Work at Waipapa Taumata Rau, The University of Auckland. Before joining the University, Aaron was a teacher and Head of English at Aorere College and a literacy facilitator at Team Solutions. Aaron’s research and development work with schools is varied and includes a focus on disciplinary literacy in senior secondary school subject areas, reading comprehension and writing in Years 4–8, and literary analysis and creative writing at all levels.

Associate investigator—Dr Selena Meiklejohn-Whiu is currently a Research Fellow working on multiple research projects at Waipapa Taumata Rau, The University of Auckland. With a background in teaching, Selena has also worked as a literacy facilitator and researcher at the Woolf Fisher Research Centre on PLSLP (Pacific Literacy & School Leadership Project), multiple Manaiakalani projects, and Te Puawai Digital Immersion cluster. Selena’s doctoral study focused on the vā, digital learning design and storytelling as a way of exploring Pacific educational identities.

Statistician—Dr Yu Liu is an experienced data analyst with a solid background in statistics, math, and financial engineering. She worked at Woolf Fisher Research Centre at Waipapa Taumata Rau, The University of Auckland for almost 5 years, having contributed to an educational research study aiming to improve student achievement outcomes for over 100 schools in areas with low socioeconomic status. Apart from education, she also has data analysis experience across industries, including banking, retailing, and financial investment.

Research partner—Kiri Kirkpatrick is a Research Facilitator for the Manaiakalani Education Trust. She has previously been a Deputy Principal and taught in Manaiakalani network classes for a number of years. She currently works with principals across the Manaiakalani network to access and evaluate student achievement data, observation data, and survey results. Kiri enjoys the conversations with fellow educators around schooling improvement for underserved communities.

Research partner—Dr Naomi Rosedale is the Research Facilitator in Literacy for the Manaiakalani Education Trust. She has been instrumental in developing and delivering the Reading Practice Intensive to participants in Manaiakalani clusters of schools. The programme centres on reading practice improvement aims and educational success in predominantly low SES communities. Naomi has teaching experience in the primary and secondary sector, and as a researcher with the Woolf Fisher Research Centre at Waipapa Taumata Rau, The University of Auckland.

Research Assistant—Peter Goodwin splits his time between teaching intermediate and primary students at St Thomas’s School and studying for a PhD in the Faculty of Education and Social Work at Waipapa Taumata Rau, The University of Auckland. His research interests focus on literacy education, disciplinary literacy, and dialogic teaching.

Research Assistant—Monica Bland has over 15 years’ experience working as a research assistant within the Faculty of Education and Social work at Waipapa Taumata Rau, The University of Auckland. During this time, she has supported researchers working across a wide range of projects within the early childhood education, primary, and secondary education sectors.

References

Bezemer, J., & Kress, G. (2008). Writing in multimodal texts: A social semiotic account of designs for learning. Written Communication, 25(2), 166–195.

Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (2000). How people learn: Mind, brain, experience, and school. National Academy Press.

Hood, N., & Hughson, T. (2022). Now I don’t know my ABC: The perilous state of literacy in Aotearoa New Zealand. Education Hub.

Johnston, M. (2023). Save our schools: Solutions for New Zealand’s education crisis. The New Zealand Initiative.

Lee, C. D., & Spratley, A. (2010). Reading in the disciplines: The challenges of adolescent literacy. Final report from Carnegie Corporation of New York’s Council on Advancing Adolescent Literacy. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Ministry of Education. (2007a). The New Zealand curriculum: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2007b). Curriculum achievement objectives by level. https://nzcurriculum.tki. org.nz/The-New-Zealand-Curriculum

NMSSA. (2021a). NMSSA Report 22-IN-2: Insights for teachers 2. NMSSA English 2019—Making meaning. Educational Assessment Research Unit (EARU).

NMSSA. (2021b). NMSSA Report 22-IN-3: Insights for teachers 3. NMSSA English 2019—Multimodal texts and critical literacy. Educational Assessment Research Unit (EARU).

Reynolds, D. (2022). What is an ELA text set? Surveying and integrating cognitive, critical and disciplinary lenses. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 21(1), 98–110.

Rosedale, N. A., Jesson, R. N., & McNaughton, S. (2021). Business as usual or digital mechanisms for change?: What student DLOs reveal about doing mathematics. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning (IJMBL), 13(2), 17–35.

Wilson, A., & Jesson, R. (2019). T-shaped literacy skills: An emerging research-practice hypothesis for literacy instruction. Set: Research Information for Teachers, 48(1). 15-22. https://doi.org/10.18296/ set.0131

Wilson, A., Rosedale, N., & Meiklejohn-Whiu, S. (2024). Piloting a T-shaped approach to develop primary students’ close reading and writing of literary texts. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 59 11), 11–19.

The appendices for this online version of the report have been removed. However, you can access them here