Introduction

Mātai Mokopuna: He Tirohanga Wairua, Hinengaro, Tinana, Whatumanawa is a research project that addresses a longstanding need to deepen knowledge and understandings about assessment within kōhanga reo. To date, assessment within kōhanga reo has not been funded, resourced, or supported at the same levels as it has within mainstream/ English-medium ECE services (McMillan et al., 2021). The implication is that kōhanga reo should approach assessment in the same way as their early childhood counterparts (McMillan, 2020). However, such conceptualisations of assessment do not align well with the kaupapa of kōhanga reo.

This project takes its name from and responds to the concept of mātai mokopuna. Introduced within Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo (Ministry of Education, 2017) as an alternative to the notions of “assessment” and “aromatawai”, mātai mokopuna involves the active participation of whānau engaged in the Māori practices of te mātai (observations), te pūmahara (thought), and te wānanga (focused discussions). Mātai mokopuna also focuses on taha hinengaro—the strengthening of the mind, thoughts, and inner beliefs; taha wairua—relatedness to the environment; taha tinana— development of the body; and taha whatumanawa—the expression of emotions, hereafter referred to as te katoa o te mokopuna (Ministry of Education, 2017; Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018).

In 2019, kaiako at Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa based in Rotorua developed their own approach to mātai mokopuna which they called Ngā Kōrero Tuku Iho (McMillan, 2020). As part of a Teacher Led Innovation Fund project, the primary focus was to develop an approach that aligned with the kōhanga reo philosophy. Guided by Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust), the process of te mātai, te pūmahara, and te wānanga, together with Te Tauira Whāriki (a model that supports discussions relating to te katoa o te mokopuna), formed the backbone of the approach. Wānanga held at the end of the project to evaluate the approach found that Ngā Kōrero Tuku Iho empowered whānau, kaiako, and mokopuna by being Māori in design, enabling the Māori language and culture to flourish, and providing opportunities for whānau, mokopuna, and kaiako to connect. The study also identified that while kaiako and whānau understood the importance of mana and te katoa o te mokopuna, they could not always identify and then articulate these things.

This TLRI project extends the work previously undertaken by Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa by deepening understanding about mana and te katoa o te mokopuna and appreciating the many ways in which kōhanga reo whānau give expression to this in the process of mātai mokopuna. In Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo (Ministry of Education, 2017; Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018), there is mention of te kōnae, a special net used within traditional Māori communities that required a collective whānau effort to take hold of the cord at the top of the net, pulling it closed, leaving only the sought-after fish. Metaphorically, the kōnae is important as it symbolises whānau tino rangatiratanga over what is noticed and made visible in connection with mana and te katoa o te mokopuna. This is also significant as Māori are not a homogenous group (Durie, 1994; Houkamau & Sibley, 2010) and may recognise elements of mana and te katoa o te mokopuna in different ways that are equally valid. Documenting the different ways whānau recognise the mana of mokopuna privileges Māori knowledge and invites new discussion between kōhanga reo whānau. Additionally, whānau gain opportunities to develop critical consciousness regarding Māori ways of “being and doing”.

Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo

In Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 1995; Ministry of Education, 2017; Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust; 2018)[1] the mana or enabling power of mokopuna is fostered through the taumata whakahirahira, or cultural settings, known as mana atua—the power of the atua; mana whenua—the power and status of the land; mana tangata—the power and status of people; mana reo—the power and status of the language; and mana aotūroa—the power and status of the environment (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2020a).

| Ngā taumata whakahirahira | Explanation |

|---|---|

| mana atua | Mokopuna learn about the different atua. They learn to respect and care for the different realms. |

| mana tangata | Mokopuna learn about their whakapapa. They learn about whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, aroha, and atawhai te tangata. |

| mana whenua | Mokopuna learn to bond to the land. They learn about where they come from. They are an integral part of their mana whenua. |

| mana reo | Mokopuna are supported to communicate in te reo Māori and recognise the sacredness of the language. |

| mana aotūroa | Mokopuna learn about the mauri and wairua, the whakapapa, and to respect and care for all things. From these relationships they begin to learn that everything is interconnected. |

(Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 1995; 2020b)

Within kōhanga reo, cultural learning experiences[2] such as waiata, mihimihi, and visits to landmarks of cultural significance, are planned in accordance with the taumata whakahirahira. The mātai mokopuna approach is used to help make sense of the ways the cultural learning experiences enhance the mana of the mokopuna by focusing on te katoa o te mokopuna.

At Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa cultural learning experiences are planned, but they are also recognised as occurring spontaneously within the routines of the kōhanga reo and home environment. The goal for kaiako and whānau is to be able to express how they see all four dimensions of the mokopuna developing as a result of each cultural learning experience. The rationale for such practice derives from the belief that the dimensions of the mokopuna do not develop in isolation from each other (Pere, 1994; Royal Tangaere, 1997). By discussing te katoa o te mokopuna, whānau and kaiako drill deep into cultural learning experiences to understand how the mana of mokopuna is enhanced. The sum total of the cultural learning experiences for each taumata whakahirahira (e.g., mana reo) shows additional ways the mana of the mokopuna is enriched over time. This report provides insights into the journey of whānau and kaiako at Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa to draw on te katoa o te mokopuna, culminating in expressions of the mana of mokopuna.

The research questions

The overarching research question for this project was:

How do whānau and kaiako give expression to the mana of mokopuna through the dimensions of hinengaro (cognition), wairua (spirituality), tinana (physicality), and whatumanawa (emotion)?

This question was explored through the following subquestions.

- What do whānau and kaiako understand in relation to mana, the taumata whakahirahira and the dimensions of hinengaro, wairua, tinana, and whatumanawa?

- How does the Te Tauira Whāriki model support whānau and kaiako discussions of hinengaro, wairua, tinana, and whatumanawa?

- What are whānau aspirations for their children and how do these influence whānau and kaiako discussions of mana, hinengaro, wairua, tinana, and whatumanawa?

Research design

The research was underpinned by kaupapa Māori methodology which validates Māori ways of knowing and being. Adherence to kaupapa Māori principles ensures Māori interests remain at the heart of kaupapa Māori research. Guiding principles include: tino rangatiratanga (self-determination), where the research provides Māori with the opportunity to take greater control of their lives; taonga tuku iho (cultural aspirations), where Māori language, culture, and identity is taken for granted; ako Māori (culturally preferred pedagogy), upholding Māori preferred ways of teaching and learning; and kia piki ake i ngā raruraru o te kāinga (socioeconomic mediation), where the research can contribute to a form of enhanced wellbeing within the home, involves whānau (extended family structure) by encouraging collective responsibility; and reflects commitment to the kaupapa (collective philosophy) or shared vision (Pihama et al., 2002; Smith, 1997; Smith, 2015). The project acknowledges mātai mokopuna as the kōhanga reo approach to assessment. This approach gives kōhanga reo whānau greater control of the way they choose to view, talk, and document learning and development. Additionally, a focus on mana, and te katoa o te mokopuna, has benefits for not only mokopuna, but also their whānau, who are culturally socialised and attuned to Māori value systems.

Kaupapa Māori research shares a number of similarities with participatory action research (PAR) that supported its use within this project. Kaupapa Māori research validates Māori ways of being and doing. Similarly, PAR recognises the knowledge and lived experiences of practitioners, that can help inform policy, and avoid the homogenisation of a “one size fits all” approach (Lawson, 2015; Mukherji & Albon, 2010).

Together, kaupapa Māori research and PAR complement each other as methodologies that empower marginalised communities (Smith, 2006).

Used as a research tool PAR empowers whānau and kaiako to take charge of their lives and ensure their voices are heard. Communities identify issues of concern and plan to address these (Eruera, 2010; Lawson, 2015; Mukherji & Albon, 2010). Research cycles enable participants to collect and analyse data to determine their next steps. These steps are also supported by research, which is then followed by another layer of data collection and reflection. PAR also allows for researchers working alongside communities to bring about the desired change. The clarifying of roles is important to ensure participants remain key drivers of the research (Baum et al., 2006).

Researcher positioning

Kaupapa Māori is research conducted by Māori, for Māori, and with Māori (Smith, 2015). Being Māori and researching for and with Māori means understanding one’s position and identity (Pihama, 2016). My whakapapa connects me to the tribal groupings of Ngāi Te Rangi, Ngāti Porou, and Ngāti Kahungunu, however I was born and raised in Rotorua. I am a first-generation manu pīrere (kōhanga reo graduate) and my four children are second-generation manu pīrere who have gone on to kura kaupapa Māori. My journey as a manu pīrere and as a mother influences my understanding of what it means to be Māori, to choose kōhanga reo, and the challenges that face whānau involved in kōhanga reo. I also share a special connection to Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa as it is the kōhanga reo I attended as a child, and the kōhanga reo I chose to return to with my own children. My youngest child was attending the kōhanga reo at the time of the research and for this reason I share a close relationship with the kaiako and whānau participants in this research.

Whānau, kaiako, and mokopuna participants

Five kaiako, one kaiāwhina, and 11 whānau (18 parents in total) from Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa consented to participate in the research. Whānau also gave consent for information about their children (14 in total) to be gathered and shared as part of the project. All participants wished for their real names, and where applicable, the names of their children to be used.

To learn how the mana of mokopuna is enhanced through cultural learning experiences over time, a small cluster of case-study mokopuna and whānau were followed over the course of the project. The selection of mokopuna and their whānau was made in consultation with the kaiako researchers. At Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa mokopuna are grouped according to their age. Kahukura and Punaromia were selected as the casestudy mokopuna because they would transition between the pēpi and nohinohi groups, and nohinohi and pakeke groups respectively during the life of the project. Kahukura’s parents, Tori and Sean, along with Punaromia’s parents, Hinewai and Tyler, completed the whānau clusters.

Research cycles

The project involved two cycles of data gathering and analysis. In each case, the data collection and analysis occurred during wānanga that routinely take place at the kōhanga reo. The types of wānanga included wānanga matawhāiti (involving kaiako); wānanga matawhānui (involving whānau); and wānanga mātātara (involving kaiako and whānau). Wānanga mātātara are referred to by Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa as Ngā Kōrero Tuku Iho (based on Māori oral traditions where history and pūrākau are passed on from one generation to the next). Further details about each type of wānanga are provided below in the Table 2 summary.

| Wānanga type | Wānanga attendees | Wānanga purpose | Wānanga frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| wānanga matawhāiti | kaiako | to discuss matters relating to teaching and learning | fortnightly |

| wānanga matawhānui | whānau | to discuss matters relating to kōhanga reo operations | monthly |

| wānanga mātātara | whānau and kaiako | to discuss the learning and development of mokopuna in relation to mana and te katoa o te mokopuna | bi-monthly, after the wānanga matawhānui |

Ethical approval for this research was gained in line with University of Waikato guidelines. In addition, kaupapa Māori research involves cultural considerations when conducting research with Māori. The following protocols outlined by Smith (1999, p. 120) were of particular importance to this research:

- Aroha ki te tangata (a respect for people)

- Kanohi kitea (the seen face, that is present yourself to people face to face)

- Titiro, whakarongo . . . kōrero (look, listen . . . speak)

- Manaaki ki te tangata (share and host people, be generous)

- Kia tupato (be cautious)

- Kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata (do not trample over the mana of people)

- Kaua e mahaki (don’t flaunt your knowledge).

The Māori cultural practice of wānanga was drawn on throughout the research to enable kaiako and whānau to come together face-to-face to talk about mokopuna development. Discussions and analysis relating to the research took place at wānanga outside the wānanga mātātara to preserve the tapu (sacredness) of this process, allowing whānau to assume their normal practices. Aroha ki te tangata and kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata were both achieved by acknowledging the important role of whānau and kaiako (as whānau) in the lives of mokopuna and as experts in their own right. Titiro, whakarongo, and kōrero was adhered to during project-related wānanga where, together with kaiako and whānau, discussions relating to the mana of the mokopuna were strengthened.

Cycle 1

Baseline data collection

Cycle 1 commenced in 2021 and lasted 3 months. During this cycle, baseline data were gathered for subquestion 1: What do whānau and kaiako understand in relation to mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and the dimensions of hinengaro, wairua, tinana, and whatumanawa? These data were gathered during a wānanga matawhāiti and the first wānanga matawhānui for the year, at which whānau discussed and recorded their understandings in relation to mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna. The wānanga was transcribed and discussed by whānau and kaiako with a view to identifying whether whānau and kaiako understanding of these terms could be strengthened and ways in which this could occur.

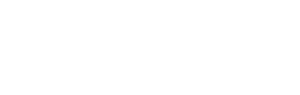

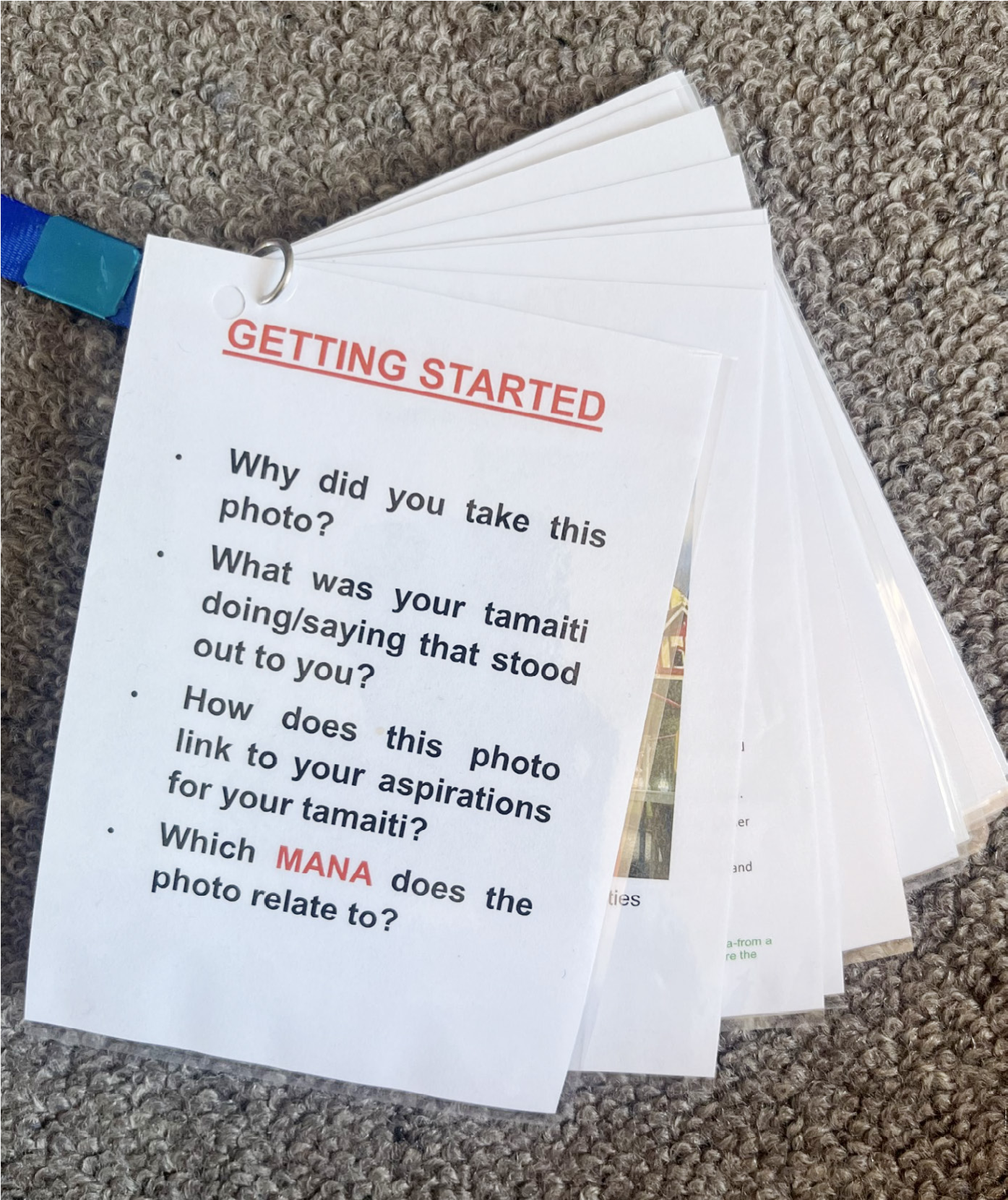

Data were also gathered at the second wānanga mātātara for the year where whānau and kaiako shared photographs and/or video clips of mokopuna engaged in cultural learning experiences at kōhanga reo and in the home. Whānau and kaiako worked collaboratively to analyse ways the mana of mokopuna was enhanced using the kōhanga reo model, Te Tauira Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2017; Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018). This model (see below left within Figure 1), which was developed by Sir Tamati and Lady Tilly Reedy, is underpinned by four kaupapa whakahaere (principles) (whakamana, ngā hononga, kotahitanga, and whānau tangata). These four kaupapa whakahaere weave together the taumata whakahirahira and te katoa o te mokopuna (see Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 1995; 2020a). Within Figure 1, the whāriki to the right provides examples of the way in which te katoa o te mokopuna can be discussed for each taumata whakahirahira.

Whānau and kaiako also made links between the cultural learning experiences and whānau aspirations for their children as an additional indication of the significance of the cultural learning experiences for mokopuna. The second wānanga mātātara was video recorded and transcribed. Copies of the photographs shared and records of whānau aspirations were also gathered.[3] Together these provided important insights relating to subquestions 2 and 3.

Data analysis

Following the gathering of baseline data, the kaiako and university researchers met during a wānanga matawhāiti to begin data analysis. This involved the kaiako working together with the university researchers to view the video recordings in conjunction with the transcripts and Te Tauira Whāriki to help make sense of the ways in which they themselves and whānau were able to talk about te katoa o te mokopuna relative to the taumata whakahirahira and to identify areas for improvement. Kaiako also discussed the data from the wānanga matawhānui that captured what whānau understood in terms of mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna. Kaiako and university researchers discussed ways in which they could strengthen whānau understanding of these terms and how wānanga matawhānui could be used as a space to respond to the needs of whānau.

The baseline data were also made available to whānau, as researchers of their own practice, during a subsequent wānanga matawhānui. Like kaiako, whānau had the opportunity to contribute their analysis of the baseline data and talk about their needs and ideas to strengthen their understanding.

After the wānanga matawhānui, kaiako and the university researchers met again at a wānanga matawhāiti to review whānau responses and decide on an intervention plan, te ara whakamua, to strengthen understanding in preparation for the second cycle of data gathering.

Te ara whakamua

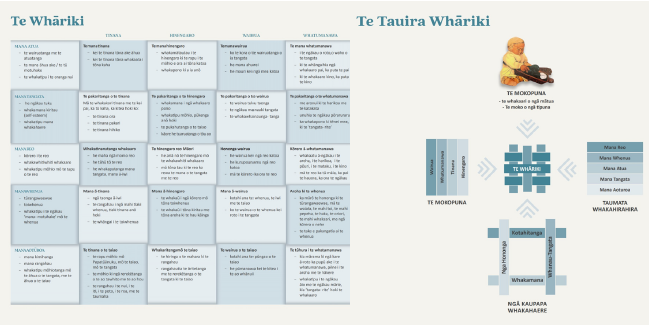

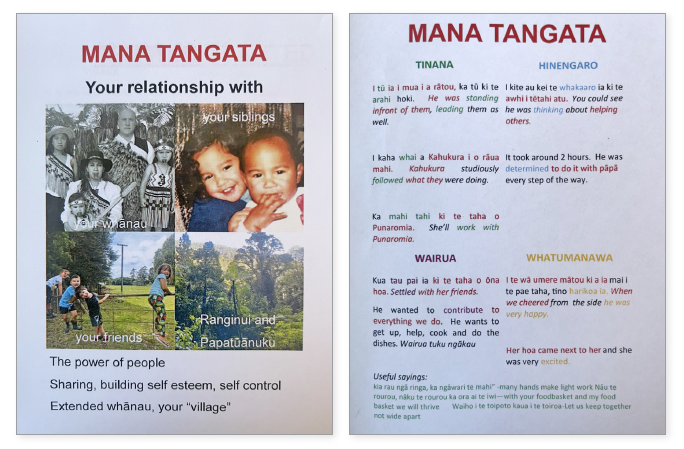

Te ara whakamua took place during the second half of 2021. It involved a multilayered approach to developing resources based on Te Tauira Whāriki. First, kaiako created a series of cards with key words and images to help explain each of the taumata whakahirahira (see the left-hand image in Figure 2 for an example). Later, cards with examples of how to talk about te katoa o te mokopuna were added for each of the taumata whakahirahira (see the right-hand image in Figure 2 for an example). Video recordings of whānau using the cards to make connections between cultural learning experiences, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna were also created for whānau and added to the kōhanga reo social media page.

During te ara whakamua, whānau and kaiako also deepened their understanding of the taumata whakahirahira through mahi toi. In small groups, whānau and kaiako selected a taumata whakahirahira, discussed the meaning of these, and images and symbols that could be used to help portray their ideas (for a detailed explanation of the artwork see McMillan et al., 2023). Whānau and kaiako then took responsibility for painting a portion of the artwork, and shared their artwork along with their explanations at a subsequent wānanga matawhānui.

Additional resources were developed to remind whānau of their aspirations for the mokopuna while at kōhanga reo and the significance of these in making sense of their observations as part of the mātai mokopuna approach.

Cycle 2

Data collection and analysis

The second cycle of data collection and analysis took place from January to June in 2022. It began with a wānanga matawhānui and a wānanga matawhāiti to discuss how whānau and kaiako understanding of mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna had changed as a result of te ara whakamua. Two additional wānanga mātātara were recorded and transcribed to capture how whānau and kaiako used Te Tauira Whāriki in their discussion of cultural learning experiences. Whānau, kaiako, and university researchers met for a final time at a wānanga matawhāiti/wānanga matawhānui to analyse the data, as described above, and to offer perspectives in terms of any shifts in understanding.

| Wānanga type | Number of wānanga: cycle 1 | Number of wānanga: cycle 2 | Data gathered |

|---|---|---|---|

| wānanga matawhāiti | 3 | 2 | Written and oral responses from individual whānau indicating knowledge of mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna. |

| wānanga matawhānui | 2 | 2 | Written and oral responses from individual kaiako indicating knowledge of mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna. |

| wānanga mātātara | 5 | 2 | Recordings of whānau and kaiako mātai mokopuna in relation to the taumata whakahirahira and te katoa o te mokopuna. Where possible, photographs shared by whānau and kaiako and records of whānau aspirations were collected. |

Case-study clusters

Data collection and analysis

All wānanga mātātara for the case-study mokopuna, Punaromia and Kahukura, were recorded and transcribed. Together, whānau, kaiako, and university researchers identified, analysed, and discussed ways each of the mokopuna had experienced growth over time according to the taumata whakahirahira and te katoa o te mokopuna, culminating in stronger visibility of the mana of mokopuna.

Key findings

The key findings in response to the overarching research question, “How do whānau and kaiako give expression to the mana of mokopuna through the dimensions of hinengaro (cognition), wairua (spirituality), tinana (physicality) and whatumanawa (emotion)?” are reported below. The findings are accompanied by Tauira which help illuminate the subtle differences in whānau and kaiako expressions.

Progressive stages of whānau and kaiako expressions

Whānau and kaiako expressions of mana, the taumata whakahirahira, and the dimensions of hinengaro, wairua, tinana, and whatumanawa were represented by one of three progressive stages. At each stage, whānau and kaiako expressions increased in complexity as whānau gained confidence and knowledge about Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo, specifically, the taumata whakahirahira, and te katoa o te mokopuna. Each of the three stages are described below.

Stage one: Te Tīmatanga

Te Tīmatanga represents the first steps of “getting to know” Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo. At this stage, the cultural learning experiences that whānau and kaiako described were connected to one of the taumata whakahirahira (e.g., mana reo or mana aotūroa).

Tauira 1

In Tauira 1, māmā Latoya describes a trip taken by her family to visit relatives they had not seen for some time. While there is a strong emphasis on reconnecting with whānau, what was important to māmā Latoya was her daughter Tvaxja’s ability to share her knowledge of te reo Māori and her role in supporting her whānau to understand. Within Tauira 1, māmā Latoya connects the cultural learning experience to the taumata whakahirahira mana reo. Māmā Latoya also comments on aspects of mana reo that were evident as a result of the cultural learning experience.

I haere mātou ki Tāmaki Makaurau ki te whakawhanaunga atu ki tōna whānau whānui. Kōtahi tau kāore mātou kua kite i tō mātou whānau ki Tāmaki. He wā tino harikoa. The two girls in there, are my best friends’ daughters and kāore rāua e mārama ki te reo. Na tōna kaha [Tvaxja] ki te kōrero Māori kāore tana whānau i te mōhio ki āna hiahia. Arā, mai i tōna whakaruarua kupu—so she kept repeating or she would have a little haka when they couldn’t understand, so she was saying kupu like ngote, pēpi, inu wai, basic kupu like that over and over, or she would give a little haka, or tohu ā matimati, or go and get that thing to show them. I put this into mana reo, mō tōna reo kia rere, because she was helping her whānau learn te reo even if it was just little kupu and so they started saying those kupu whenever they were with her like, “Do you want inuwai?” “Do you want wharepaku?”, little things like that. So, I thought it was cool that she was able to āwhina and whāngai te reo Māori ki tōna whānau (Māmā Latoya, wānanga mātātara, April 2021).

According to Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo, the taumata whakahirahira mana reo provides for cultural learning experiences that promote the sacredness of the language, encourages the mokopuna to communicate, and understand the Māori world, “kia mōhio i te rangatiratanga, i te tapu me te noa o tōna ake reo. Kia matatau te tamaiti ki te whakahua i te kupu. Kia mōhio ia ki tōna ao, te ao Māori” (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018, p. 20). Within Tauira 1, Latoya comments specifically on Tvaxja’s ability to communicate in the ways articulated in Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo through the use of her body language and repetition.

Tauira 2

In Tauira 2, māmā Tireni describes a cultural learning experience involving her daughter Hihiwa in the outdoors which she directly links to mana aotūroa.

Ko te whakaahua o tēnei wāhanga mō te wānanga mātātara ko te mana aotūroa. Ko te whāinga o tō mātou nei whānau mā Hihiwa ki te tūhura ki te taiao. He akomanga te taiao ki a mātou ki te kāinga. Kei te tino pirangi mātou te whakakaha tana hononga ki te whenua. He maha ngā mea kei te ako kei waho rā. He pai mō te orangatanga, te whanaketanga, te puāwaitanga. He pai a Tāwhirimātea, te hau mō te tinana, te hinengaro, ēra atu wāhanga o te whanaketanga o te tamaiti. Ko tēnei te whakaahua, he iti ake a Hihiwa i te pikitia. Kei te aro ia ki te rākau. I ngā hararei i haere mātou ki Waipoua, ki te ngahere, ka tūtaki ai ia a Tānemahuta, [he] rawe. Ko te wairua ki reira he tino tau, tino tau. Ko ngā tangata katoa ka noho wahangū, [he] rawe. Ko te tamaiti, ko Hihiwa, kāore ia i te tino noho tau. Kei te pirangi ia ki te piki i te kēti me ēra atu momo, tino tūhura, [he] pai ake ki a mātou ki te mātaki i a ia. (Māmā Tīreni, wānanga mātātara, April 2021)

In Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo, the taumata whakahirahira fosters mokopuna connections with the environment, “kia mōhio he wairua tō ngā mea katoa: te whenua, te moana, te ao whānui, ngā whetū, te hau, ngā rākau, ngā ngāngara” (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018, p. 24). Tireni’s choice of kupu highlights her focus on mana aotūroa through the use of terms such as tūhura, taiao, Tāwhirimātea, and Tānemahuta. The use of the kupu Tāwhirimātea and Tānemahuta especially emphasise a world seen through a Māori lens. Additionally, Tireni uses the phrase “he akomanga te taiao ki a mātou ki te kāinga” signalling the importance of the outdoors to her whānau as a place where mokopuna can learn and thrive.

Stage two: Te Whanaketanga

As whānau and kaiako became familiar with the taumata whakahirahira (see Table 1), they started thinking and talking about two or three of the taumata whakahirahira (i.e., wairua, tinana, hinengaro, whatumanawa) that make up te katoa o te mokopuna. For example, connecting a cultural learning experience to mana reo and being able to articulate how the experience showed growth in terms of taha hinengaro (cognitive development) and taha whatumanawa (emotional development). This progression in whānau and kaiako thinking represented the next phase of expressions relating to the mana of mokopuna and is referred to here as Te Whanaketanga.

Tauira 3

In Tauira 3, one of the kaiako, Whaea Tori, describes a cultural learning experience involving Rākena, who was interested in a specific outdoor toy. Whaea Tori links the cultural learning experience to mana reo and reflects on Rakena’s taha whatumanawa and taha hinengaro.

Ko tēnei taku whakaahua mā Rākena. Ia wā ka puta mātou ki waho, kōtahi atu a Rākena ki te rua kirikiri. Engari i tēnei rangi korekau he taonga ki reira. Takahi ōna waewae, i hāparangi hoki ia “taraka, kei hea taraka?” Kite au i te hōhā me te tīmatanga o te riri e pupū ake ana i a ia. I haere au ki te wharau ki te tiki he taraka māna. I whai mai a Rākena engari i ahau e whiriwhiri ana i tētahi taraka, ka kōruru tōna rae, ka kohete mai “kāo”. I ngana hoki ia ki te whakamārama mai ki au ko tēhea te mea tika engari nā te hōhā me te riri tē taea. Ka heke au ki tōna taumata me te kii “me āta haere, me āta whakaaro kia mārama pai a Whaea ki ō hiahia”. Ka tiro mai ia ki au, ka wahangū, ka kitea au i tōna hinengaro e huri haere ana. Na te āta whakaaro ka wātea tōna hinengaro, ka puta te pai. Ka toro atu tōna ringa me te kii “kikorangi”. Nā reira ka tango au i tēnei whakaahua nā te mea i kite au i panoni tōna āhua i a ia e āta whakaaro ana. Ka whakaaro pai, ka puta te pai. Āe, ka harikoa ka mauri tau hoki ia i te rironga o tana taonga nā reira ka hono au i tēnei ki te mana reo me te wawata kia ako i te reo. Āe kei te ako a Rākena ki te whakawhiti whakaaro (Whaea Tori, wānanga mātātara, April 2022).

Within Tauira 3, Whaea Tori noticed Rākena’s frustration and then attempted to find out the cause of his frustrations. She did this by getting down to Rākena’s level and encouraging him to slow down and think in order to articulate what he wanted. After some time Rākena stretched forth his hand and used the word “kikorangi”. Evidence of Rakena’s ability to think and then respond with the appropriate kupu is referred to by Whaea Tori as a sign of his hinengaro. The reflections on Rākena’s emotive reactions or whatumanawa signalled to Whaea Tori that Rakena was also able to use his emotions as a form of communication.

Stage three: Te Puāwaitanga

As whānau and kaiako became confident in talking about a few dimensions (hinengaro, wairua, tinana and whatumanawa), they were able to work on the remainder, bringing to a close te katoa o te mokopuna and signalling their ability to flourish, Te Puāwaitanga. Another important feature of Te Puāwaitanga was the ability of whānau and kaiako to connect cultural learning experiences to whakatauki.

Tauira 4

In this example, Whaea Heather describes a cultural learning experience involving Zeivian and the confidence he displayed as he danced during waiata time. Whaea Heather foregrounds the discussion with a whakatauki and then discusses the cultural learning experience in relation to te katoa o te mokopuna and the taumata whakahirahira, mana atua.

“He kokona o te whare i kitea, he kokona o te ngākau e kore i kitea”. Rata a Zeivian ki te kanikani manu, that bird song. Tino hīkaka te ngākau, hiki āna tukemata, pūkana karu me te menemene nui i te wā tīmata te rangi o te waiata. Ko te taha whatumanawa tēra.

Mōhio ia ki ngā piki me ngā heke o te rangi me ngā nekehanga kori tinana. Mārama hoki mēna ka tere haere, pōturi rānei te pao o te rangi, ka tere neke, pōturi rānei te kanikani. Ko te taha hinengaro tēra. Kaha wiriwiri te katoa o tōna tinana, pekepeke, hurihuri, pakipaki me te tārere i ōna ringaringa, me tōna māhunga hoki. Ko te taha tinana tēra. He tamaiti tino whakamā, noho wahangū te nuinga o te wā, kīkīa tōna wairua i te hari me te koa, ā ko te taha wairua tēra. E hono te whakaahua, tēra whakaahua ki te mana atua. Ka taea e ia te patu i te whakamā. (Whaea Heather, wānanga mātātara, April 2022)

Whaea Heather uses the whakatauki “He kokona o te whare i kite, he kokona o te ngākau e kore i kitea”—meaning a corner of a house may be seen and examined, but not so the corners of the heart— to describe Zeivian’s unseen characteristics and attributes. By doing this, Whaea Heather links this cultural learning experience to the taumata whakahirahira mana atua, where children recognise their “mana atuatanga” or godlike characteristics and attributes (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018, p.16). Whaea Heather proceeds to describe Zeivian’s confidence in recognising the changing tones of the waiata and his ability to respond accordingly (hinengaro), his confidence in using his bodily functions by jumping, turning, clapping, throwing his hands and head (tinana), confidence to ‘give it go’ as evident by his excitement and facial expressions (whatumanawa), and relaxed and content nature (wairua). Whaea Heather explains why this is significant as Zeivian is quiet and will typically sit and observe.

Ko te whakatipu i te mana o te mokopuna

The case-study mokopuna provided important insights into the mana of each mokopuna, and growth over time.

Kahukura

The following tauira are a collection of the kōrero shared by Kahukura’s parents during the project. They have been purposefully selected because they relate to the same taumata whakahirahira, mana tangata. Each tauira offers new perspectives about Kahukura’s growth and mana as a result of the cultural learning experiences relating to mana tangata. It is important to note that the tauira represent different points in the project, and where whānau were at in terms of their own understanding. For this reason, the tauira may be a combination of the different stages described above, and which are acknowledged in brackets below.

Tauira 5 (Te Tīmatanga)

In Tauira 5, māmā Tori shares her observations of a cultural learning experience involving Kahukura helping to wash the dishes alongside her brothers. After describing her observations, Tori explains what was important to notice in this interaction. Specifically, she talks about the whakawhanaungatanga, or the act of building relationships, and Kahukura’s developing kiritau, or sense of worth. Māmā Tori proceeds to make explicit links to the taumata whakahirahira, mana tangata.

Koinei taku whakaahua. I tērā rā i āwhina a Kahu ki te whakapai i ngā rīhi. I tīmata ōna tungāne ki te whakapai rīhi a muri i te kai. I kaha whai a Kahukura i ō rāua mahi. I thought this was a cool photo, experience and mahi that Kahukura got up to because it was something spontaneous. We have got into this thing at home where the boys are old enough now to help with cleaning up and doing the dishes and trying to foster that independence and growing pūkenga, looking after yourself, helping others, that kind of thing. They were doing that and Kahukura came along and she really wanted to help out, so we gave her a mahi. We were like, ahakoa he pēpi koe ka taea e koe te āwhina. We gave her some things to dry, just if you can see by her concentration there, she was going hard and she was enjoying that mahi, and following that positive example from her brothers. He contribution kia whakapakari i tōna kiritau, whakapakari i ōna pūkenga. I would put this under mana tangata. Kei te whakatipu mōhio me āna pūkenga. He hua nui mai i tēnei ko te whakawhanaungatanga. Pērā i te mahi ki te marae, āwhina ki te whakapai, doing the dishes after hākari and having all your whanaunga around. And even though it sounds like a boring mahi, it’s a time where we can have conversations, get to know each other a bit better, have a little bit of quality time, and also help each other out. So that was a big thing for me, is that whakawhanaungatanga, so I would hono that to that wawata. Āe and harikoa ia ki te āwhina. I kite au tērā nā tana hiahia ki te āwhina. We didn’t ask her to come and help, she just came and did it on her own. (Māmā Tori, wānanga mātātara, April 2021)

In Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo, cultural experiences relating to mana tangata involve connections with people: “Kia mōhio ki ōna whakapapa, ki te pātahi o te whānau, ki ōna hoa, whānau whānui; ki ōna kaumātua; ki a Ranginui rāua ko Papatūānuku” (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018, p.18). They also include opportunities to build self-esteem. Tori deepens her analysis of the cultural learning experience by explaining the similarities of Kahukura’s actions to interactions that occur naturally on the marae.

Tauira 6 (Te Tīmatanga)

Tauira 6 is shared by Kahukura’s father, pāpā Sean, who shares a cultural learning experience involving Kahukura and her Barbie doll friend. Pāpā Sean connects the cultural learning experience to the taumata whakahirahira mana tangata.

The other day when Kahukura and her māmā were going to the kura to collect Kikorangi and Ihaia, pēpi Kahukura had her little Barbie girl doll and she was speaking to Barbie as if she was her hoa. She was speaking in te reo Pākehā at the time and Tori said to her she should kōrero Māori instead and she proceeded to say the exact same things she said in te reo Pākehā in te reo Māori. We try to kōrero in te reo Māori as much as we can at home but sometimes we catch the kids not speaking te reo Māori. But I think in this situation because Kahukura had translated exactly what she had already said, Whaea Tori was quite impressed by that because it demonstrates knowledge of her being able to kōrero but also an acknowledgement that we do need to live in te ao Pākehā me te ao Māori. It really shows that she is growing in confidence to walk comfortably in both worlds. She is becoming very adept at her kōrero Māori and she growls me because sometimes I don’t kōrero as much as I should. She is keeping everybody in line, she knows when papa is not doing the right thing. I was tossing up with this one, whether it would fit best with mana reo or mana tangata but I think in the end I chose mana tangata because it is a good demonstration of her relationships with different people in her life. As I said before, sometimes we have to walk in te ao Pākehā because life makes that necessary and to show that she can move so seamlessly through both depending on the situation made me sort of feel like it wasn’t only to do with her reo but also her relationships with people and being able to adjust that based on the situation and that’s why I decided on mana tangata. As far as our wawata for her, just growing in confidence and exploring different things, it really resonated with us. (Pāpā Sean, wānanga mātātara, February 2022)

Of importance to Sean was Kahukura’s ability to talk to her friend in both English and te reo Māori, albeit after some prompting from her mother Tori. Being able to accommodate people in different situations is one way mokopuna can build relationships and take care of their friends. This is a key focus of the taumata whakahirahira mana tangata: “Kia kaha te āwhina i a ia ki te whakahoahoa, ki te manaaki anō hoki i ōna hoa me ōna pakeke” (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2018, p. 19).

Tauira 7 (Te Puāwaitanga)

In Tauira 7, the focus returns to Kahukura’s relationships within her whānau, specifically Kahukura’s relationship with her older brother Ihaia. Within it, Māmā Tori connects the cultural learning experience to mana tangata and talks about Kahukura’s growth in relation to te katoa o te mokopuna.

Anei taku whakaahua whaea. Kei te awhi a Kahukura i tōna tungāne a Ihaia. Ki ētahi kāore he hohonu pea tēnei whakaahua engari ki ahau nei he tauira pai hei whakaatu i te aroha i waenga i a rāua. Kua mauria mai hoki au tēnei whakaahua tawhito nō te wā i konei a Ihaia me te wā pēpi a Kahukura. E ai ki aua kōrero he tungāne rawe a Ihaia, ka nui tōna aroha mōna. He tika tērā. Neke atu i te toru tau ki muri kua puāwaitia te aroha. Ka awhi a Kahukura i a Ihaia, ka kihi, ka waiata hoki. Me tana kī “Ihaia my darling”. Kua tau pai ia i te taha o tōna tungāne, kua harikoa hoki. Ka menemene mai tōna katoa i ahau e tango whakaahua ana. Na te tauira me te āwhina a tōna tungāne e mōhio ana a Kahu ko ia tētahi tangata haumaru, tētahi tangata manawanui. Ko te tūmanako he kaha tō rāua hononga mō āke tonu. Kua hono tēnei ki te mana tangata. Ka whakaatu mai i tōna ngākau tuku, te aroha, me te manaaki. He aroha whakatō, he aroha puta mai. (Māmā Tori, wānanga mātātara, October 2022)

Tori looked back at a photograph of Ihaia when he was at kōhanga reo, hugging and embracing Kahukura, and one of Kahukura three years later, where she was now able to reciprocate and verbalise her aroha for her brother. Considered alongside Tauira 5, it is clear that Kahukura has continued to strengthen her relationship through whakawhanaungatanga with her siblings. Tori also uses a whakatauki to explain the significance of the cultural learning experience within the Māori world, “He aroha whakatō, he aroha puta mai” meaning “if kindness is sown, then kindness you shall receive”.

Summary

Combined, Tauira 5, 6, & 7 illustrate the growth in Kahukura over an 18-month period in relation to mana tangata and her ability to forge and maintain relationships with those around her. Kahukura values her relationships with her whānau and friends, a sign of her mana āhua ake.

Punaromia

The tauira relating to Punaromia have been selected for two reasons. First, because of the connection between cultural learning experiences shared by both the kaiako and whānau at the same wānanga mātātara. Secondly, because of the visibility of different aspects within each dimension of te katoa o te mokopuna, highlighting ways the mana of the mokopuna has been enhanced.

Tauira 8 (Te Puāwaitanga)

In Tauira 8, Punaromia’s māmā Hinewai shares her observations of her at home as they play with clay and proceed to talk about Matariki.

Mō te wā roa ko tō rātou kōrero Matariki tēnei, Matariki tērā, Matariki tēnei, Waitī, Waitā, Waipunarangi. Mo tērā wikene i tiki au i te clay. I thought I would be a cool mum, pull it out and do some crafts. I cut the kids each a piece and let them do what they wanted with it and Punaromia sat there for a while not sure what she was going to do. And then I got on with my clay and found this little, I think it was from your shaker [talking to Tyler] or something and pushed it in to the clay and it actually made a star and her whole face lit up ooh Matariki, her taha tinana. After that she was so focused on, I think she was making the constellation, she was making the holes and counting the holes and trying to name them all and that sort of stuff. Everything was Matariki in the moment and she was so focused on her task and I have just been enjoying the learning for the whole month about Matariki. Like taha hinengaro, coming home and learning her kupu for the whakaari on Friday, teaching us things about Matariki that we didn’t know about, like who is Waitī, who is Waitā, and she is so fixated on kāo he tama tērā. I have to pull out my notes to see if she is right so her hinengaro just blows me away. In that moment, she really enjoyed spending time with māmā, quality time, doing something together that they enjoyed was really special. Taha wairua, the confidence knowing all of that about Matariki and how settled she was doing the activity, initially not knowing what to do, turned into having a purpose, and turned into a kōrero about Matariki which was really special. We ended up baking the clay and pulled it out and painted it with nail polish so she has this little treasure at home with her little star that she really adores. He hononga tērā ki mana aotūroa. I think we need to update her wawata, tērā pea, ko ngā waiata Māori because through that all we were also singing (Māmā Hinewai, wānanga mātātara, June 2022).

Tauira 9 (Te Puāwaitanga)

In Tauira 9, Whaea Heather shares her observations of Punaromia at kōhanga reo as the rōpū pakeke practice their whakaari in preparation for the kōhanga reo Matariki celebrations.

We made some mōhiti with a connection to the whetū. We are prepping for our whakaari and have been practicing every day. Pakari haere te nekehanga a Punaromia i roto i te rōpū pakeke. Hīkaka tōna ngākau. Ko te taha tinana tērā. Tino pakari ngā pūkenga me ngā mōhiotanga e pā ana ki ngā whetū. Ētahi mōhiotanga, ko wai ngā tama, ko wai te māmā, e hia ngā whetū, ko wai ngā ingoa, ko wai ngā kōtiro. Ngā mōhiotanga anō ka tiaki tēhea whetū i tēhea wāhi o te taiao, ko te taha hinengaro tērā. Tino āio ia, tino pakari hoki te tiaki i a ia i te tuatahi, me ōna hoa, tuarua. Kaha ia ki te manaaki i ōna hoa i waenganui i ngā akoako, ko te taha wairua tērā. Ko ōna pūkenga anō, ka tohaina i ngā mahi ki ngā teina, ka kohete i ngā tuakana. Ka whakatikatika i a rātou kōrero, ka kōrero ngāwari ki ngā tēina. Ko te taha whatumanawa tērā. Ka hono tēnei ki te mana tangata, me te wawata kia mau ki te mahi kaihautu, ki te manaaki rānei (Whaea Heather, wānanga mātātara, June 2022).

While Hinewai and Heather apply a different lens to their observations of Punaromia, they notice similar things, such as Punaromia’s ability to name the stars within the Matariki cluster and whether the star is a tama or kōtiro. There are also some differences in relation to each of the dimensions that signal growth in different variations. For example, Hinewai describes wairua in terms of wairua tau, whereas Heather describes wairua using the term manaaki. Another example are the expressions of the tinana and the way the body can be used. Hinewai’s account of Punaromia’s use of her tinana was to create something, whereas Whaea Heather focused on the way the tinana could be used to convey the messages of the whakaari alongside her peers.

Accounts of the mokopuna taking knowledge from one setting to another is an additional indicator of enhanced mana. Royal Tangaere (1997) has previously documented the ability of mokopuna to transfer te reo Māori from kōhanga reo to the home. Punaromia’s interactions build on what we know about mokopuna language and cultural transference between kōhanga reo which is significant given some of what Punaromia was sharing was new to her whānau.

Summary

Tauira 8 and 9 show examples of Punaromia’s growth in relation to individual dimensions (hinengaro, wairua, tinana, and whatumanawa). When viewed in this way, the mana of mokopuna can also be enhanced through changes in each of the dimensions over time.

Implications for practice

This project has offered insights into how kaiako and whānau can give expression to the mana of mokopuna. The findings have supported the notion that there are many ways to give expression to the mana of mokopuna as influenced by the aspirations of parents, knowledge of the taumata whakahirahira and te katoa o te mokopuna. To give expression to te katoa o te mokopuna is also a progressive learning journey as whānau and kaiako find new ways to carve and shape out mātai mokopuna from Māori perspectives.

This project offers unique perspectives on the way whānau both inside and beyond kōhanga reo can be involved in mātai mokopuna or the assessment process. Too often whānau are relegated to “not knowing”, or “untrained”, yet the findings of this research suggest otherwise. The expressions of whānau in this research were on a par with kaiako who supported and nurtured their ability to observe and make sense of mokopuna observations through opportunities to learn about Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo. As whānau developed rich understanding of the curriculum they were better able to make deep and meaningful contributions to discussions about their child’s development.

For educational services there is potential to reconsider and reimagine the way in which we see the role of whānau in the lives of learners. For kōhanga reo, there has always been an expectation that whānau are actively involved in the learning and development of mokopuna, but this is not necessarily a view shared by the education sector as a whole, and to the degree evident in kōhanga reo. Reimagining the role of whānau would require educational services to relinquish some of the power and responsibility that currently resides with kaiako, creating space for whānau to sit alongside them in an equal capacity; a willingness to support whānau to learn about the curriculum in ways that make the most sense to them; and the humility to accept whānau as experts in their own right, and from whom kaiako can also learn. In doing so, a strong representation of learning and development is woven together that represents the totality of the child’s world. The processes used by Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa could also be valuable for other kōhanga reo in thinking about how whānau might be supported to understand the curriculum and contribute to it at the kōhanga reo and in their homes.

This project focused on ways kaiako and whānau give expression to the mana of mokopuna, in doing so it has also reinforced Māori ways of being and doing. It contributes to a growing body of evidence that outlines what matters most in kōhanga reo. Engaging with this body of knowledge opens a pathway to understanding. Generating understanding will help avoid hegemonic discourses which impact on Māori lives, and the ongoing prejudice of kōhanga reo.

Limitations

This research is based on the journey of one kōhanga reo. While kōhanga reo are connected through our fundamental philosophies and curriculum, each may breathe life into these differently. That is to say that not all kōhanga reo will use wānanga as a way of talking about the mana of mokopuna and may choose to convey this knowledge in other ways that works for their community.

Conclusion

Kōhanga reo plays a fundamental role in supporting mokopuna to realise their mana. By opening the door to conversations about the mana of our mokopuna we remind them of who they are, where they are from, and all they can be in this world—“ka tū rangatira rātou i roto te ao whānui” (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2022, p.11). We become stronger as whānau, and kōhanga reo, championing kaupapa Māori with our mokopuna in mind.

Footnotes

- The published version of Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo by the Ministry of Education varies from the final draft produced by Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust. While both versions are acknowledged throughout the report, the Trust version was used by the kōhanga reo and for this reason it is the only version referenced in relation to the outcomes of the project. ↑

- See Royal Tangaere (2012) for further discussion and examples of cultural learning experiences. ↑

- Copies of any video clips shared by kaiako or whānau were not made as these were audible in the recordings of the wānanga mātātara. ↑

References

Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979), 60(10), 854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662 Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora: Māori health development. Oxford University Press.

Eruera, M. (2010). Mā te whānau te huarahi motuhake: Whānau participatory action research groups. Mai Review, 3, 1–9.

Houkamau, C. A, & Sibley, C. G. (2010). The Multi-dimensional Model of Maori Identity and Cultural Engagement. New Zealand Journal of Psychology (Christchurch. 1983), 39(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1037/ t19427-000

Lawson, H. A. (2015). An introduction to participatory action research. In H. A. Lawson, J. Caringi, L. Pyles, J.

Jurkowski, & C. Bozlak (Eds.), Participatory Action Research (pp.1-35). Oxford University Press.

McMillan, H. (2020). Mana whenua / Belonging through assessment—a kōhanga reo perspective. Early Childhood Folio, 24(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0074

McMillan, H., Mitchell, L., Shaw, T., Patu, H., Parekura, A., Tihema, J. H., Rewita-Grace, L., Urlich, V., Ruri, A. (2021). Mātai mokopuna—he tirohanga wairua, hinengaro, tinana, whatumanawa. http://www.tlri.org.nz/ tlri-research/research-progress/whatua-t%C5%AB-aka/ma%CC%84tai-mokopuna-%E2%80%93-hetirohanga-wairua-hinengaro-tinana

McMillan, H., Shaw, T., Patu, H., Parekura, A., Tihema, J. H., Urlich, V., & Shaw, K. (2023). Making sense of Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo through toi Māori: A whānau approach. Early Childhood Folio, 27(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.271.2023

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/ Documents/Early-Childhood/Te-Whariki-a-te-Kohanga-Reo.pdf

Mukehrji, P. & Albon, D. (2010). Research methods in early childhood: An introductory guide. Sage.

Pere, R. (1994). Ako: Concepts and learning in the Maori tradition. Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust.

Pihama, L., Cram, F., & Walker, S. (2002). Creating methodological space: A literature review of kaupapa Māori research. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(1), 30–43.

Pihama, L. (2016). Positioning ourselves within kaupapa Māori research. In J. Hutchings & J. Lee-Morgan (Eds), Decolonisation in Aotearoa: Education, Research and Practice (pp. 101–113). NZCER.

Royal Tangaere, A. (1997). Learning Māori together: Kōhanga reo and home. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Royal Tangaere, A. (2012). Te hokinga ki te ūkaipō – A socio-construction of Māori language development: Kōhanga Reo and home [Doctoral thesis, University of Auckland, New Zealand]. Research Space@ Auckland.

Smith, L.T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. University of Otago.

Smith, L.T. (2006). Researching in the margins: Issues for Māori researchers—A discussion paper. Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples (2)1, 4–27.

Smith, L. T. (2015). Kaupapa Māori research—some kaupapa Māori principles. In L. Pihama & K. South (Eds.), Kaupapa rangahau a reader: A collection of readings from the Kaupapa Māori Research Workshop Series (pp. 46–52). Te Kotahi Research Institute.

Smith, G. H. (1997). The development of kaupapa Māori theory and praxis. [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/2292/13392/whole. pdf?sequence=2

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust. (1995). Te Korowai. [Unpublished]. Chartered agreement between the Ministry of Education and Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust on behalf of the Kohanga Reo whanau (1995– 2008).

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust. (2018). Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo. https://www.kohanga.ac.nz/te-reo/tewhariki-a-te-koohanga-reo

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust (Producer). (2020a). Wererou Te Whāriki Tuatahi. https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=DIca3jDUvrI

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust (Producer). (2020b). Wererou Te Whāriki Pt 2 Final. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=1uk6s3MJpE0

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust. (2022). Te Korowai. [Revised Internal document]. Chartered agreement between Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust Board and Te Kōhanga Reo whānau.

Research team

Hoana McMillan is a lecturer at the University of Waikato. She is a kaupapa Māori researcher committed to research within kōhanga reo. Her recently completed doctoral research focuses on intergenerational whānau perspectives of educational success in kōhanga reo.

Email: hoana.mcmillan@waikato.ac.nz

Linda Mitchell is a professor of early childhood education at the University of Waikato. She has spent many years researching and critiquing early childhood education policy and researching with teachers in action research projects. Her current TLRI-funded research, Renewing Participatory Democracy: Walking with Young Children to Story and Read the Land, also includes Te Kohanga Reo ki Rotokawa and Hoana McMillan as a research associate.

Email: linda.mitchell@waikato.ac.nz

Ngā kaiako o Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa

Tiria Shaw, Heather Patu, Abigail Parekura, Jannalee Hano Tihema, Victoria Urlich (kaiako), and Kamorah Shaw (kaiāwhina) are based at Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa in Rotorua. The kōhanga reo is a past winner of the Prime Minister’s Education Award for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.

Email: whanau@k05a015.kohanga.ac.nz