1. Introduction

This 2-year participatory action research project explored how learning to use narrative assessment supported teachers’ inclusive practices for disabled[1] secondary school-aged students who are considered to be working long term in Level 1 of The New Zealand Curriculum (NZC) (Ministry of Education, 2007). Narrative assessment is an assessment for learning process underpinned by sociocultural perspectives on curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment that documents learning for disabled students. It uses a combination of photographs and/or videos of students’ learning experiences alongside narrative descriptions that connect with the NZC key competencies and learning areas.

To date in Aotearoa New Zealand, assessment for disabled students has been largely for diagnostic purposes or for applying for resources (e.g., Ongoing Resourcing Scheme [ORS]). The ongoing focus on deficits is demoralising, both for the families of disabled students and for their teachers. It has also meant that many teachers cannot see the relevance of NZC or assessment tools and practices for every student (Morton et al., 2023; Morton et al., 2012).

Access to learning opportunities is often determined by assessment practices that inform teaching, in particular assessment for learning. NZC describes teaching as inquiry as fundamental to ensuring the success of all students (Ministry of Education, 2007). Effective inquiry in turn requires quality assessment for learning.

Yet government agencies (e.g., Education Review Office, 2014; Human Rights Commission, 2014) in Aotearoa New Zealand express concern that disabled students continue to be excluded from assessment processes. These reports recognise that improvements in educational outcomes for disabled students are unachievable if the students are not being assessed.

Narrative assessment: Recognising disabled students as learners

Narrative assessment is an assessment for learning process based on Carr (2001) and subsequently Carr and colleagues’ work on learning stories as a narrative approach to assessment in early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand (Carr et al., 2005). Carr’s work became part of the foundation for a research project that grew out of the Ministry of Education’s desire to develop resources that would support teachers whose students were considered to be working long term at Level 1 of NZC. Narrative Assessment: A Guide for Teachers (Ministry of Education, 2009a) and The New Zealand Curriculum Exemplars for Learners with Special Education Needs (Ministry of Education, 2009b) were developed out of this project. These resources were designed to help teachers notice, recognise, and respond to students’ learning with a focus on the key competencies within the context of the learning areas of NZC.

Over 2 years, 26 teachers met with curriculum facilitators to learn how to use narrative assessment to document learning and plan for teaching, and to report what they were learning to families and to other teachers. The resources were mainly focused on literacy and numeracy in the curriculum, and most were for students and teachers in the primary school sector. The teachers who participated in the project described a profound impact on their relationships with their students and students’ families. The teachers said they were not only seeing their students through different eyes, but themselves through different eyes also. Recognising their students as learners meant that teachers were more confident in their role (Ministry of Education, 2009a; Morton et al, 2012). More recent work with small groups of teachers in primary schools (McIlroy, 2017) and in one secondary school (Guerin, 2015) continues to show the potential of these resources to support teachers’ use of formative assessment to guide their teaching as inquiry by using evidence to scaffold their teaching (Hill et al., 2017).

The present project

Although the Ministry of Education has provided teachers with a range of exemplars to make sense of how narrative assessment can support learning and teaching (Ministry of Education, 2009a, 2009b) there are gaps within the learning strands that have been presented within the exemplar range to date. For example, many of the exemplars at the secondary school level draw solely from the Physical Education and Arts learning areas. This project aimed to address this imbalance through writing exemplars across a wider range of learning areas. It was envisaged that teachers within the study schools would use narrative assessment across all curriculum areas.

The three project aims were to:

- investigate how narrative assessment would impact on teachers’ thinking about disabled students’ learning, as well as on their teaching practices for disabled students

- examine how any changes in teachers’ thinking and teaching impacted on the learning and social experiences of disabled students (e.g., participation in extracurricular activities and events and friendships)

- expand the current resource The New Zealand Curriculum Exemplars for Students with Special Education Needs (Ministry of Education, 2009b) to include more exemplars in secondary academic subject areas.

This project ran from January 2019 to September 2021 and was a collaborative partnership between three researchers and three schools. The research team comprised:

- Missy Morton (principal investigator), Professor of Disability Studies and Inclusive Education, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland (UoA)

- Dr Jude MacArthur, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education and Social Work, UoA

- Dr Anne Marie McIlroy, Ministry of Education, Wellington.

Two secondary schools (St Kevin’s College, Oamaru and Naenae College, Wellington) were involved and one special school (Kimi Ora Special School, Wellington) (see Table 1 for school demographics).

| School | School type | School decile | School population | Ethnic composition |

| St Kevin’s College, Oamaru |

Coeducational Catholic secondary school Years 9–13 |

7 | 450 | Māori 10% Pākehā 70% Pacific 5% Asian 10% |

| Naenae College, Wellington | Coeducational secondary school Years 9–13 |

3 | 750 | Māori 31% Pākehā 25% Pacific 24% Asian 11% |

| Kimi Ora Special School, Wellington | Special school | n.a. | 70 | Māori 10% Pākehā 58% Pacific 8% |

In addition to the three researchers, the final project team included nine teachers, a teacher aide, three school leaders, five students, and their whānau. The process of inviting the eventual teacher and student participants took place in the first term of the project, following more detailed explanation of the aims of the project. Teachers needed to be working with students who had either been considered eligible for individualised funding through the ORS,[2] or for whom at least one application had been made for ORS funding. The students and families of participating teachers needed to have first consented to participation in the project. However, once the project got underway, the resources developed were available to all in the school who were interested.

The project was guided by three research questions:

- In what ways can narrative assessment processes support teacher inquiry?

- In what ways does using narrative assessment impact students’ academic and social achievement?

- What does assessment for learning look like for assessment capable teachers and students at secondary school?

Ethical approval for the project was obtained from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee. All participants, including students, gave informed consent to participate in the research. This required information and consent forms to be presented in multiple formats to support the access and communication strengths of each participant.

Informed consent was sought from students, their whānau, teachers, and school principals on two occasions. As each participant entered the project, consent was obtained for collecting materials as described in Table 2 and sharing these materials across the research team members. As materials were developed for sharing beyond the initial research teams (for example, presentations and publications), informed consent was again sought specifically for sharing identities and images. Therefore, participants’ real names are used with their permission.

2. Research design, data collection, and analysis

This was a participatory action research project (Erfan & Torbert, 2015). Our initial design was for a 2-year project. The impact of the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns saw the project extended by 6 months. In this project, we started with existing relationships with three schools. Bringing teachers from the three schools together and with the research team provided an opportunity for shared inquiry into the teachers’ and their schools’ assessment practices.

Prior to the project, the partner schools had already each begun inquiring into their own pedagogical and assessment practices with disabled students. This project was a response to problems in practice expressed as current learning and assessment needs by the schools. The participating schools, as well as the researchers, were interested in describing and understanding the thoughts and actions of teachers, teachers’ aides, students, and their families as they began learning about and using narrative approaches to assessment:

- How did each of the project participants understand and use narrative assessment?

- What impact was narrative assessment having on student achievement?

- How did narrative assessment shape teachers’ and families’ expectations for and of students?

The project used qualitative methods for data collection and analysis to explore shared questions to understand assessment beliefs and practices as well as the impacts of those practices on students, their families, and their teachers in three partner schools. An overview of the time frames and data collection strategies is presented in Table 2.

| Time period | Focus areas | Data collection sites and strategies |

| Term 1 2019 to Term 4 2019 |

|

Combined School and Research team meetings

School-based meetings with leadership teams

Interview/discussions with families and students

|

| Term 2 2019 to Term 1 2020 |

|

Combined School and Research team meetings

School-based meetings with participating teachers

|

| Term 2 2020 to Term 4 2020 |

|

Combined School and Research team meetings

School-based meetings with participating teachers

Whole-school workshops led or co-led by project teachers

|

| Term 1 2021 to Term 3 2021 |

|

Interview/discussions with families and students (often shared examples of previous student reports)

Interview/discussions with individual teachers and school leaders

|

The three researchers worked with participant teachers, students, and families in Term 1 of 2019 to gain informed consent and to describe current experiences, practices, understandings, and expectations. In Term 2, we introduced information about narrative assessment of the key competencies in the context of the learning areas. We made use of the published resource Narrative Assessment: A Guide for Teachers (Ministry of Education, 2009a) and The New Zealand Curriculum Exemplars for Learners with Special Education Needs (Ministry of Education, 2009b). Introducing these resources provided opportunities for all research participants to think about how their schools may wish to frame assessment within their own unique context. Researchers and teachers worked in partnership to examine shared understandings of pedagogy and power as schools considered the purposes and consequences of their use of assessment.

During the remainder of 2019 and over 2020 we worked with teachers as they investigated their understandings, expectations, and practices about assessment and about student learning. We engaged in formal and informal conversations, attending to any changes in both individual teachers’ and school-wide assessment practices. We discussed the ways teachers undertook assessment; how they used assessment information; and how they shared assessment data (including how the information informed the Individual Education Plan [IEP] process for students, as well as informal communications with other educators and families). In 2021, we explored new expectations for assessment and learning with the project teachers, students, and families.

Data collection

The project generated rich qualitative data including transcripts of audio and video recordings of discussions with students, their whānau, and their teachers. Such discussions took place in a variety of configurations such as between one researcher and an individual (teacher, student, or parent); between a researcher and a pair of teachers; or amongst all the teachers in the project together. It wasn’t always possible or appropriate to use a recording device, and, on these occasions, researchers wrote reflection notes afterwards. Examples of these kinds of occasions include phone calls or during informal meetings (e.g., in the staff room, walking across a school campus) when teachers shared questions, reported on an exciting example of student achievement, or their own and/or others’ new insights.

A second main source of data was existing or created documents. These took the form of reports shared with families or schools prior to the introduction of narrative assessment. A further source of documents was the recording of the new ways teachers were collecting, describing, and sharing what they recognised as student learning. As teachers developed and refined their use of narrative assessment, including seeking input from students and families, the presentation of narrative assessments changed. For some of the students, a final form of documentation was material that was used or submitted to demonstrate achievement in National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) credits.

Data analysis

Data analysis in this project was thematic, iterative, and collaborative. Interpretivist thematic analysis (Mills & Morton, 2013; Taylor et al., 2016) was conducted over three phases.

The initial thematic analysis was organised around key ideas generated from researcher and teachers separately and jointly. This allowed our different perspectives to be visible and valued in our beginning analyses. This approach also ensured that participant voices and understandings went beyond mere member checking (Harrison et al., 2001) of themes identified by the researchers. The teachers were invited to read across summaries of discussions and the narrative assessments written by other teachers, noting what “stood out for them”. In this first approach, six initial and larger themes were identified. These larger themes included: recognising learning; curriculum and curriculum planning; voice and agency; collaboration; partnership; and planning.

The research team led the second phase of analysis which involved considering which of these themes were common across all the project participants and across the three schools. For example, teachers recognised students’ learning, they also saw themselves as learners. As student agency and voice was increasingly visible, vocal, and present, students were increasingly involved and even led collaborative planning. Where partnership and planning had initially focused on curriculum and assessment for the students in the project, teachers and school leaders saw opportunities for making changes to wider school assessment systems and processes.

The final phase of analysis was sifting through the identified themes to see how these themes addressed the research questions and aims of the project. Themes were grouped and re-grouped to address different elements of the questions. Themes are now presented grouped by research question in the final section.

3. Key findings

In this section, we present our key findings in response to each of the three research questions. In presenting our findings, names and photographs of all participants and participating schools in the examples are used with their permission.

RQ1:

In what ways can narrative assessment processes support teacher inquiry?

Teachers developed an understanding of the student and their capability which was made more visible, and of their own agency as teachers to recognise, respond to, and support student and teacher learning. Narrative assessment enabled them to examine the big picture goals of education around citizenship and belonging in a community, and to appreciate that relationships and knowledge sharing amongst teachers, students, whānau, and community members are central to an inquiry process that fosters quality teaching, learning, and assessment. Goals for student learning were co-constructed between student, whānau, and teacher with a shared commitment to the processes and contexts in which those goals would be achieved.

An example of teachers and teaching teams developing their inquiry approaches is shared below.

Supporting mathematical inquiry

Tina is a senior high school teacher and a Special Education Needs Co-ordinator (SENCO). This is a management position that includes responsibility for enabling students who need additional support to be successful. Tina had long recognised the NCEA structure was not particularly relevant for several students, including Jacob. At the time of the research, Jacob was in Year 12 and supported to engage in classroom learning. Because Jacob was not working towards many NCEA credits, his learning as a Year 12 student was not very visible to classroom teachers. Tina explored narrative assessment, hoping it might help her and other teachers find a way to recognise Jacob’s learning success and raise his profile as a learner in his subject classes.

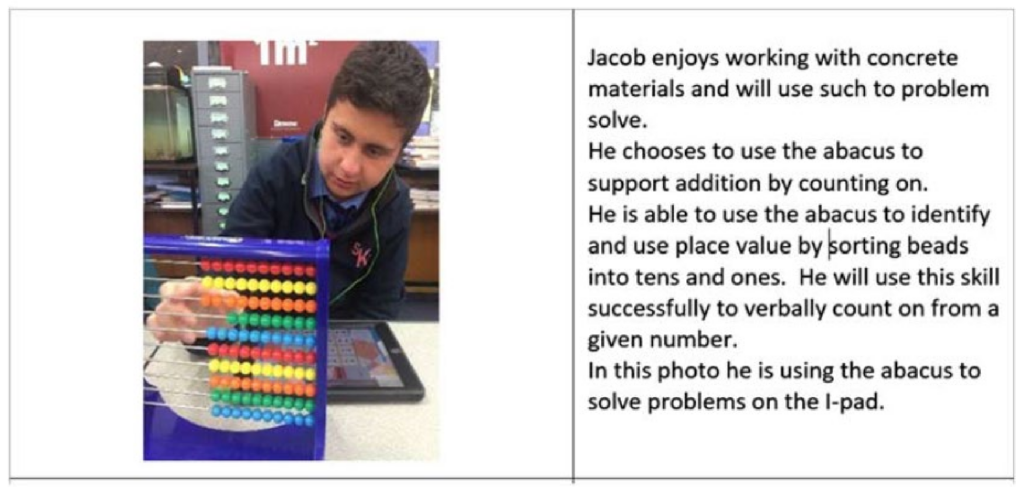

Jacob was engaged in a personalised maths programme with goals from Level 1 of NZC in a class of Year 12 students working on NCEA Level 2 algebra credits. The maths teacher, Ryan, saw that narrative assessment provided an approach to record Jacob’s progress. The teacher’s aide, Sue, provided in-class maths learning support for Jacob. She taught his programme and gathered evidence of his learning in the form of written comments and photographs. Tina used this evidence to structure the narrative assessments of Jacob’s maths learning with help from Sue. The narrative assessment grew over two terms to become an ongoing assessment of Jacob’s maths learning.

Because the narrative assessment was a live document, evidence of learning was added on an ongoing basis. This accessible structure enabled the classroom teacher to include his observations and analysis of Jacob’s learning. Ryan saw one of the photographs in the narrative assessment showing Jacob successfully solving a place value problem. He commented on the evident mathematical skills and thinking demonstrated by Jacob and added this mathematical knowledge to the narrative assessment. Ryan stated that the narrative assessment enabled him to better understand Jacob, and the teacher became more actively involved in teaching him. This included sharing ideas with the teacher’s aide, providing resources, and checking out more of what Jacob was doing as Ryan roved the classroom supporting the senior students.

The maths team used the developing narrative assessment as a springboard for discussing ongoing teaching and learning opportunities in the classroom. Tina recognised the narrative assessments were strengthened when specific subject knowledge was added. Narrative assessment meant Jacob’s learning progress became increasingly visible and this facilitated a stronger pedagogical connection between all educators supporting Jacob’s maths learning.

As Tina became more aware of the opportunities to recognise learning through narrative assessment, she became more critically reflexive of the practical links between goals, teaching, and assessment and more focused on the relevance of students’ programmes.

Jacob’s learning was determined by his interests and strengths. This meant some NCEA credits in subjects such as art were desirable and achievable, but NCEA did not dominate the assessment landscape for Jacob. The narrative assessment process enabled Tina to focus on “learning that’s really useful for Jacob”. This meant Tina was more focused on inquiry-based learning as she reflected on ongoing progress and achievement to determine next learning steps towards goal achievement for Jacob.

Tina recognised that her focus had shifted from supporting Jacob to engage in and complete set tasks in class alongside his peers, to recognising how Jacob was engaging in the learning, and responding to him in a way that facilitated his learning. Documenting learning through narrative assessment meant learning progressions were noticed, recorded, and reflected on to support teaching and learning that made sense for Jacob. Processes became as important as outcomes.

Attention to smaller steps in Jacob’s learning trajectory meant the team supporting him became more aware of his interactions within learning contexts, and what lessons or parts of the school day were most motivating and meaningful for Jacob. As a team, the adults reflected together on what they had noticed and used this data to make Jacob’s learning opportunities more motivating and successful. Analysing Jacob’s responses meant teaching pedagogy adapted in an ongoing way to foster his engagement and success. Ongoing assessment is a critical aspect of maintaining teacher engagement and student motivation.

Tina was interested in how narrative assessment could facilitate teacher inquiry through a strengths-based lens to support inclusive practice and the authentic belonging of students across subjects and teachers in a complex secondary school context (Skidmore, 2002). Her curiosity has been piqued, and she is now enrolled in postgraduate study to explore inclusive education more deeply.

RQ2:

In what ways does using narrative assessment impact student academic and social achievement?

Students enjoyed enhanced participation and achievement within NZC which became the focus for teaching and learning. Some students achieved NCEA credits in drama, creative writing, and art, but NCEA did not dominate the assessment landscape; rather, teachers focused on learning that capitalised on students’ strengths and interests and was considered most relevant and useful for the student. Learning was recorded and fostered across people and places, home, and school. Narrative assessment effectively linked teaching, learning, assessment, and reporting as it became a format for reporting to and celebrating learning with whānau.

An illustration of this finding is shared below.

Achievement in NCEA captured

Lucas was a senior student in his final year of secondary school at the time of this research project. Lucas demonstrated huge empathy when listening and spoke in a gentle and thoughtful way, responding appropriately to different contexts. At school, these strengths were evident in drama, where his communicative skills were recognised and encouraged. Lucas achieved the NCEA drama credits he wanted and enjoyed this subject. Over the year, Jo, Lucas’s drama teacher, recorded his learning progress in a narrative assessment. Film of Lucas performing, photos, and writing make this narrative assessment a rich and enduring record of learning (Morton et al., 2021). It was a valuable formative assessment process, as reflecting on the developing narrative supported teacher pedagogy, enabling the teacher and Lucas to work together and make ongoing changes to support success (Wiliam 2011).

Lucas also enjoyed creative writing in English, combining his knowledge and interest in world war history with imaginative storylines. Lucas’s goal was to achieve credits in creative writing. His English teacher, Tina, recorded Lucas’s learning in a narrative assessment over two terms.

Lucas had spent the previous year working towards these credits but had not completed the mahi (work). He began the new year determined to succeed. Lucas’s voice is recorded in the narrative assessment, and he stated “This year I have sorted out what I am doing with my studies. Sitting down, head down and getting right into my creative writing.” In the narrative assessment, Tina wrote, “This year Lucas has started school with a confident mind-set and has set a goal of completing the English Standard AS91101, Creative Writing. Lucas has already demonstrated an ability to craft his writing using vocabulary and language techniques appropriate for his chosen genre.” Having access to assistive technology supported greater writing accuracy, enabling him to focus more on creativity. Throughout this narrative assessment, the teaching commitment to support Lucas to achieve his goal is very visible. Tina’s pedagogical unpacking of Lucas’s writing shows an ethic of care not usually visible in assessment processes. In Lucas’s story, he wrote “War—Great Britain WW2 1969. We were under attack”. Tina records this excerpt in the narrative assessment, and she writes, “The ‘1969’ date for this creative writing is an opportunity for me to have a discussion with Lucas later. That date is not an error of fact. It is a story for me to uncover.” Tina explained that approaching this with Lucas as a fact to correct could irreparably harm Lucas’s willingness to write freely and share his work with her and could damage his selfconfidence. Tina describes the date as “our opportunity to understand Lucas and recognise his subconscious creativity”. Tina wrote, “his [Lucas’s] creativity is innate—this is not something that’s been taught”.

|

Tina The ‘1969’ this date for this creative writing is an opportunity for me to have a discussion with Lucas at a later time. That date is not an error of fact. It is a story for me to uncover. |

||

|

Tina Lucas uses visual language, painting a picture of the soldiers dying in battle and colloquialism as he describes having ‘piss all ammo left’. Lucas successfully paints a picture with words in the statements. Lucas is a visual learner and in his writing he creates visual images for others to read. |

Tina’s care for Lucas’s mana and her willingness to understand his thinking demonstrates her belief in Lucas’s capability. Tina does not place herself in a position of power with control and answers, but as a coconstructor of learning alongside Lucas. Tina’s pedagogy embodies the concept that assessment shall do no harm, and that quality teaching demands care and kindness (Noddings, 2012).

In the narrative assessment, Tina records all the language features that Lucas demonstrated in his writing. She also includes the pedagogy that supported Lucas’s mastery. Lucas achieved the writing credits as he had planned. Tina said more important than the credits is that if Lucas chooses to read this narrative assessment in the future “he’ll be reminded that he was a success at school, that he had teachers who believed in him, family who believed in him, and nothing can take that away”. In this example, narrative assessment highlighted Lucas’s success and the pedagogy that enabled the success.

RQ3:

What does narrative assessment for learning look like for assessment-capable teachers and students at secondary school?

As teachers saw the relevance and value of the curriculum for every student, they described improvements in their own curricular knowledge and stronger narrative assessments appearing out of their own subject knowledge. In paying attention to small steps in student learning, teachers became more aware of the context (people, lessons, parts of the school day) that were most motivating and meaningful for the student. Teachers and students both felt validated as students progressed towards more complex learning goals. As an iterative process that recognises current progress and signals next teaching steps, narrative assessment demanded collaborative and critically reflexive planning that values and includes the thinking of whānau, students, and teachers. School-wide process and systems also changed to effectively record teaching and learning and celebrate success.

An example illustrating this finding is shared below.

Brooke and Malaya—partnership in learning

Malaya is beginning her journey through the secondary years of school and Brooke is her classroom teacher. Malaya communicates in ways other than speech. She uses a PODD (Pragmatic Organisation Dynamic Display)—a high-tech communication tool based on using visual discrimination to communicate a message. Additionally, Malaya uses head movements to indicate yes or no and facial expression to communicate emotion. Malaya chooses her communication system. For simple, quick responses she may choose head movements as they readily enable social participation and conversation. When Malaya has something complex to say or is initiating communication, she may choose to use her PODD. Malaya’s whānau always knew Malaya had strong receptive communication but, without shared understanding and commitment from communication partners, Malaya has limited opportunity for expressive communication. Brooke shared the whānau belief and said, “Malaya has much to say, has firm opinions and is keen to share her thoughts both at home and at school.” Brooke recognised it was her role as teacher to ensure Malaya had effective accessible communication systems to enable her voice to be heard. Brooke’s teaching philosophy is based on democratic principles where all students are equally valued and are partners in learning. Brooke said “I run my classroom in a democratic way. It’s student driven based on students’ rights; and the students plan their own learning journey. My focus is on their rights to be heard, to play, to socialise, to be educated and to be respected.” Brooke describes herself as a facilitator of learning. Her classroom programme is built around the interests and strengths of the students and is meshed in the learning areas of NZC. Key competencies are embedded within the learning which is underpinned by values and principles (Ministry of Education, 2007).

In Brooke’s classroom, teaching, planning, and assessment are collaborative and include all learners. An example of this collaboration is visible in physical education lesson planning. Malaya has never been an enthusiastic participant in physical education and has frequently expressed her opposition to participation. However, she is a Harry Potter fan, and Malaya indicated to Brooke that she wanted to play quidditch. Malaya helped write the class “Quidditch Game Rules”, and, with support from a broader team, the context was created so all students could play the game. Participation was enabled by ramps so the wheelchairs could navigate the quidditch court; balls that made a noise so those students who have a cortical vision impairment could see the ball, and large clear targets. Brooke reports that Malaya’s face lit up when she saw the quidditch court and that she was totally involved in all aspects of the game which turned out to be a fierce competition involving all the class. Narrative assessment provided the means not only to share the learning outcomes of the quidditch game, but to make visible the collaborative planning, Malaya’s voice, the ongoing interactions, the successes and Malaya’s reflections. At home after the game, Malaya used her PODD to tell her whānau that she “loved quidditch” and the game was “exciting” and “fun”.

An overarching aspect of Brooke’s philosophy is her belief that all students are capable and can learn and demonstrate their skills and knowledge when teachers are enablers (Kliewer et al., 2015). Brooke has high expectations of all her students and high expectations of herself as a teacher. An example where Malaya’s capability was made visible was during English, when each class member was engaged in creative writing. Using a range of communication supports, Malaya indicated she wanted to write a poem. Malaya selected a title for her poem, the vocabulary she wished to use, the order and structure of the poem, and how it was to be presented. This did not happen in one lesson but with perseverance over time. On completion, the poem was printed in large font on a background that enabled Malaya to see the text. Malaya asked that the poem be mounted on purple card. The photograph (Figure 3) shows Malaya’s pleasure in seeing the published poem she created.

The process of creating the poem was recorded in a narrative assessment and shared on Story Park—the school’s electronic platform used to connect teacher, students, and whānau. Malaya’s mum and dad read the narrative assessment on Story Park and said:

Before narrative assessment we didn’t know she was into writing at all particularly creative writing like poetry. We had no idea till we saw the narrative assessment and now we do writing with her at home. So, we’ve now got her an email address and a Facebook page.

Malaya’s whānau read Story Park at home with Malaya and with her brother and sisters. They felt connected to her learning and were able to extend her interests at home, merging both of her worlds together. The structure and sharing of narrative assessment provided a learning connection between home and school that opened Malaya’s world. Her mum and dad particularly enjoyed the images accompanying the narrative saying, “we can see the learning … we get to understand what’s going on with her learning … we can see how she is valued (at school) and how she gets her own voice and her own independence”.

Brooke’s thoughts on assessment

Brooke recognised that summative assessment processes often used to monitor progress didn’t capture the achievements and potential of the students she taught. Brooke was committed to making the achievement of small learning steps visible regardless of whether a goal was attained. She said:

summative assessment wasn’t showing capability and wasn’t showing the small successes and the big successes my class were making. Most of our class learn for a long time in level 1 of the NZC, and those little successes build up to become huge successes and we can show that through narrative assessment.

Narrative assessment is a process that supports effective pedagogy. Brooke said, “narrative assessment enabled me to delve deep and reflect on the learning”. This reflection is both of Malaya’s learning and Brooke’s teaching, a critical process that led Brooke to continually adapt and change her learning programmes to best enable students to be and to feel successful.

The steps that teachers take to build caring relationships and foster wellbeing are visible in the respectful and celebratory way in which Brooke’s narrative assessments for Malaya are written. Brooke valued an approach that made her beliefs evident. Brooke said:

I knew she [Malaya] was amazing and capable, but I didn’t have a way to make that visible. Narrative assessment gives us a way to do that and shows everyone else and Malaya that we value her. Through Malaya’s narrative [assessment] we see her personality shine through. We can see that she is kind, empathetic, funny, generous, and clever, that she loves literacy, hates PE, and isn’t a fan of maths but will give it a go, and we see it all in her narrative assessments. Narrative assessment helps teachers to see students through a strength-based lens, you can’t see any deficits when you write narrative assessment. The personality shines through and the strengths shine through … All the wonderfulness that is Malaya is in her narrative assessments.

For Brooke, narrative assessment highlights the strengths of formative assessment as a process for supporting ongoing teaching and learning. This is particularly relevant for her disabled students as it enabled her to show their capabilities, their successes, and their belonging in the learning areas of NZC.

School leaders’ reflections on the move to narrative assessment

Schools’ values reflect their unique culture; they are beliefs that the school community identifies as most important for its students to thrive in Aotearoa New Zealand’s diverse communities, guiding everything that is said and done in a school. Paul Olsen, Principal at St Kevin’s College, has described how moving to narrative assessment has supported teachers’ recognising their abilities to respond equitably to all students. He describes the impacts of narrative assessment on what the participating teachers have learnt. Paul notes that narrative assessment:

affirms the teacher’s role and responsibility for the teaching of every student in their class. I hope that when teachers see the growing suite of narrative assessments they can reflect on how equitably they have responded to all students on their class lists. Jacob’s year twelve maths experiences are an example of him being welcome, belonging and learning. In theory there was always an expectation that Jacob would learn, but narrative assessment makes Jacob’s capability visible. [The narrative assessments] are important evidence of learning. They describe context, teaching pedagogy, scaffolding and application.

Students like Jacob are now able to participate and achieve in the NCEA system. Teachers are also rethinking how they approach teaching and assessment for other students.

4. Implications

To better understand their students, teachers need to also understand all the ways, all the places, and the various contexts in which students demonstrate what they know and can do. An understanding of learning as being stretched across people, places, and things; with an understanding of competence as being context dependent, of necessity means that people must work together to build shared meanings of competence and learning. Students and their families are expert partners in the assessment practices that support teachers to plan for, recognise, and value learning.

There are many ways to get started using narrative assessment. Important “ingredients” include:

-

- finding a critical friend who has been using narrative assessment for a while (e.g., what are some of the questions you have about assessment approaches, do these approaches show students’ learning, how to make better use of NZC)

- building a team for shared inquiry, a team that includes a teaching colleague, the student, and the student’s whānau

- meeting regularly as a team to share successes, worries, and plans for next steps

- celebrating the learning of all team members.

Partnership is a central theme in understanding and sharing student learning across home, school, and community settings. Key learnings across teachers and schools suggest that narrative assessment supports teachers to reflect on their role as a teacher for all students, the complexity of teaching and learning, and their developing pedagogy. It invites conversation about inclusion and school cultures that support student belonging and learning and enables school leaders and teachers to think differently about local and responsive curriculum. Critically, narrative assessment is less about serving the system and more about serving student and teacher.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, traditional secondary school assessment focuses predominantly on learning outcomes linked to achievement in the NCEA. NCEA is a high-stakes assessment system and has a significant role in determining ongoing tertiary learning opportunities for students. It is a system that rewards academic excellence and is determined by the number and level of credits achieved. While NCEA has flexibility, it does not recognise the learning of all students. The students at the centre of this work have not been well served by NCEA.

Narrative assessment usually leads to strengthening knowledge of, and planning for learning within, NZC for all students. In some settings, greater use of NZC may be a new approach that requires conversations with colleagues and leadership support.

Using narrative assessment can point out shortcomings in some existing approaches to assessment. This can lead to useful (if initially difficult) conversations about changes in emphasis or application of assessment practices as well as subsequent reporting mechanisms.

Footnotes

- We use the term “disabled students/children/young people” in this report. We respect that some individuals or groups prefer the term “person with a disability”. Placing the word “disabled” first is consistent with the identity first language used within various disability rights’ groups such as the Disabled Persons Assembly NZ and it is the language used in the New Zealand Disability Strategy: https://www.odi.govt.nz/nz-disability-strategy/ ↑

- https://www.education.govt.nz/school/student-support/special-education/ors/overview-of-ors/#who ↑

References

Carr, M. (2001). Assessment in early childhood settings: Learning stories. Paul Chapman.

Carr, M., Jones, C., & Lee, W. (2005). Beyond listening: Can assessment practice play a part? In A. Clark, A. T. Kjorholt, & P. Moss (Eds.), Beyond listening: Children’s perspectives on early childhood services (pp. 129–150). The Policy Press.

Education Review Office. (2014). Towards equitable outcomes in secondary schools: Good practice. Author.

Erfan, A., & Torbert, B. (2015). Collaborative developmental action inquiry. In H. Bradbury (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of action research (pp. 64–75). SAGE Publications.

Guerin, A. (2015). “The inside view”: Investigating the use of narrative assessment to support student identity, wellbeing and participation in learning in a New Zealand secondary school. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

Harrison, J., MacGibbon, L., & Morton, M. (2001). Regimes of trustworthiness in qualitative research: The rigours of reciprocity. Qualitative Inquiry, 7(3), 323–345.

Hill, M. F., Ell, F., Grudnoff, L., Haigh, M., Cochran-Smith, M., Chang, W.-C., & Ludlow, L. (2017). Assessment for equity: Learning how to use evidence to scaffold learning and improve teaching. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 24(2), 185–204.

Hipkins, R. (2010). More complex than skills: Rethinking the relationship between key competencies and curriculum content. Conference on Education and Development of Civic Competencies, Seoul (pp. 1–17). New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Human Rights Commission. (2014). Making disability rights real: Whakatūturu ngā Tika Hauātanga. 2nd report of the independent monitoring mechanism of the convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Author.

Kliewer, C., Biklen, D., & Peterson, A. J. (2015). At the end of intellectual disability. Harvard Educational Review, 85(1), 1–28.

McIlroy A. (2017) “The myth of inability”—exploring children’s capability and belonging at primary school through narrative assessment. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch.

Mills, D., & Morton, M. (2013). Ethnography in education. SAGE Publications.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2009a). Narrative assessment: A guide for teachers. Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2009b). The New Zealand curriculum exemplars for learners with special education needs. http://www. throughdifferenteyes.org.nz/

Morton, M., MacArthur, J., & McIlroy, A. (2023). Using disability studies in education to move from individualised assessment to partners in pedagogy. In R. Tierney, F. Rizvi, K. Ercikan, & G. Smith (Eds.), Elsevier international encyclopaedia of education (4th ed.) (352-361). Elsevier.

Morton, M., McIlroy, A-M., MacArthur, J., & Olsen, P. (2021). Disability studies in and for inclusive teacher education in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Inclusive Education. Published online 15 February 2021.

Morton, M., McMenamin, T., Moore, G., & Molloy, S. (2012). Assessment that matters: The transformative potential of narrative assessment for students with special education needs. Assessment Matters, 4, 110–128.

Noddings, N. (2012). The caring relation in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 38(6), 771–781.

Skidmore, D. (2002). A theoretical model of pedagogical discourse. Disability, Culture and Education, 1(2), 119–131.

Taylor, S. J., Bogdan, R., & DeVault, M. (2016). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource (4th ed.). Wiley. Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.

The project team

Researchers:

- Missy Morton and Jude MacArthur, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland. Project contact: missy.morton@auckland.ac,nz

- Anne-Marie McIlroy, Ministry of Education, Wellington

Partner schools and teachers:

- St Kevin’s College, Oamaru:

- Paul Olsen

- Jo Walsh

- Tina Dooley

- Ryan Gower

- Sue Booth

- Naenae College, Wellington:

- Tamsin Davies-Colley

- Kimi Ora Special School, Wellington:

- Jess Hall

- Sarah Robinson – Brooke McCord