Introduction

Our study highlights how principal leadership of goal-directed practices impacts outcomes. Over 2 years, three academics partnered with three principals and a small “project team” comprising one or more teachers, and one or more middle or senior leaders. All principals were relatively new to their schools; one had been there 2 years, and the other two had been there 12 months prior to the beginning of the project. Two schools were secondary schools (Schools A and C) serving low socioeconomic communities. The other school was a primary school (School B) serving a high socioeconomic community which was challenged by having large numbers of new immigrants—particularly from Asia—and with students with behavioural issues. In this report, we reflect on some of the key changes that occurred from the beginning of the project to the end of the project and what behaviours appeared to impact on outcomes most strongly.

Goal-setting for school improvement

Goal-setting is a particularly important leadership behaviour that has a significant impact on student achievement and school improvement (Hallinger & Heck, 1998; Latham & Locke, 2006; Leithwood et al., 2004;

Robinson et al., 2008). Effective goal-setting is characterised by creating a few specific and clear goals. However, New Zealand school leaders often set too many unspecific goals and struggle to keep a sustained focus on their goals over the course of the year (Bendikson et al., under review). This project aims to understand how principals can lead more effective goal-setting practices and improve equity in student outcomes.

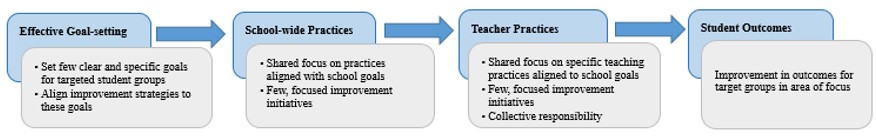

Goals can help leaders and teachers to narrow their focus and concentrate their collective effort on a prioritised area of need (Bryk et al., 2015; DuFour & Mattos, 2013). It is the collective problem-solving associated with reaching the goals that leads to more coherent organisational practices that then result in more focused, specific, and consistent teaching practices in classrooms. In turn, these benefit student learning and improve outcomes. Figure 1 presents the so-called causal chain of how school goal-setting impacts on student outcomes.

FIGURE 1: Causal chain of how school goal-setting impacts on student outcomes

Recent New Zealand research undertaken in 31 secondary schools by two researchers on the team (Bendikson and Meyer) indicates that, on average, school leaders set four broad improvement goals but they tend to set many more targets (Bendikson et al., under review). Barriers to greater school improvement seem to lie in the lack of goal clarity, misalignment of improvement strategies, and limited capacity of schools to keep a sustained focus on goal achievement. Only about half of the senior leaders and less than half of the middle leaders in these schools were able to accurately recall their school goals at the end of the year. Further, only about a third of school leadership teams seemed to have a shared understanding of their improvement agenda. Finally, the research indicated that a school’s goal focus frequently decreased over the course of the year. A limitation of Bendikson et al.’s research was a lack of comparative primary school data. Another limitation was the lack of focus on gaining equitable outcomes. This project addressed these limitations.

This project

The overarching research question informing this project was: How can principals lead goal-setting effectively to improve equity in student outcomes? Our first aim was to understand what was currently happening in the three schools in terms of goal-setting for school improvement. Secondly, we aimed to identify enablers and barriers to effective goal-setting in these schools. Our final aim was to support the development of more effective practices in these schools and thus the outcomes for priority learners. The project tested the theory that where within-school leadership is strongly goal-focused, improvement is likely to occur.

To achieve our aims and answer our research questions, principals and researchers inquired together into potential constraints to school improvement and equity in each school. Principals then used a practitioner inquiry approach to address the constraints identified and worked with their wider leadership team (including middle leaders) to improve their goal-setting and school improvement efforts accordingly. This collaborative problem-solving helped to build the principal’s own leadership capacity as well as that of their wider leadership teams. To support this team effort and capacity building, the project budgeted to include two staff members (teachers, middle or senior leaders) per school in project review and planning meetings. In this way, a networked learning and leadership approach was supported, and ultimately contributed to a more coherent team effort to use goal-setting effectively.

Research design and methods

The researchers undertook staff (five per school) and principal interviews, and observations at the beginning of the study and provided schools with an overview of the nature of goal-setting practices in the schools by drawing up short case studies of each school. Principals then used a practitioner inquiry approach (Timperley et al., 2014) to address the constraints identified in their school and improve their goal-setting and school improvement efforts accordingly. Schools were supported by the researchers through observations of and feedback on school meetings, in-school sessions aiding the schools’ problem-solving, and regular workshops to share progress and problem-solve.

There were seven half-day workshops in total which focused on reflection, problem-solving, and planning next steps. The principals and their nominated three to six staff members participated in the project over the 2 years. Workshops involved all three schools and thus enabled within- and across-school discussion, support, and feedback.

The project collected various sources of data over the 2 years. For this report, we draw on interview data, workshop artefacts, and observation notes. We interviewed each principal for an hour at the beginning (BOP), middle, and end of the project (EOP). We also interviewed five staff, including senior and middle leaders and teachers, at each school at the beginning and end of the project for half an hour. We further collected notes on school meeting observations and audio-recordings of workshop discussions. Audio-recordings were transcribed for analysis. We also used self-evaluation rubrics to assist the schools’ inquiries but are not drawing on those data for this report as their value was largely in focusing the project groups’ discussions in workshops on what they achieved and their next steps.

Key findings

In the following we illustrate our findings in regard to four goal-setting aspects: goal focus; goal monitoring; strategies for improvement; and collective responsibility. We discuss examples of the observed practices in the three schools in regard to each aspect to exemplify successes and challenges in the schools. Finally, we discuss our findings in regard to the practices we observed and their perceived impact on equity in student outcomes.

Goal focus

Three important themes were evident in the schools’ goal focus: the level of goal clarity; the process of goalsetting; and the strength of the principals’ justification of the goals and targets to staff.

Goal clarity

All three principals were well aware of the need to have few and clear goals. At the beginning of the project, both secondary schools (Schools A and C) had high levels of goal clarity because they used a short mantra (i.e., 90/90/85 or 14+), referring to the percentage levels of attainment they wanted to achieve in the three National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) levels or the number of credits that each student needed to achieve in each subject. The primary school (School B) focused on an immediate priority that the principal had identified on arriving at the school—the reduction of disruptive behaviour. She also committed to continuing a long-term focus of the school on improving written language levels because she could see that the level of achievement was not as high as she expected from her past experience in similar schools.

By the end of the project, staff in all schools were clear on their goals, but staff in Schools A and B did not necessarily know the level of the targets, whereas in School C, the one simple 14+ target that they retained over the course of the project remained highly memorable. By way of contrast, School A had three separate goals but by the end of the project they had 13 associated targets. The result was that none of their staff could recount all the targets when interviewed, but all could recite two or three of the goals. Furthermore, they knew the teachers’ role, which, just as in School C, meant supporting students to gain at least 14 plus credits in their subject. In School B, again, the goals were clear but the exact levels of the targets were not necessarily clear to staff. Despite not having clarity of the exact targets, staff at all schools knew what their improvement agenda was. The goals were very clear, even if the specific percentage level of the targets was not always.

The process of goal-setting

The process of setting these goals was similar in all schools. At the beginning of the project, all three leaders were quite directive in their approach to target setting as new principals to the schools, and became more consultative as time moved on. Staff in all schools felt “told” as opposed to feeling like partners in creating the goal focus initially.

For example, at the beginning of the project, staff at School A’s involvement in goal setting was negligible. Their perception was that the goals were “done to us” and the principal agreed. From her point of view, however, this was necessary as there was clear evidence of underperformance when their results were compared to schools with similar demographics. She felt she could not wait for buy-in but had to forge ahead. The amount of staff input increased in the 2 years thereafter, though it was still largely limited to senior leaders:

Initially I would say it was decreed, the … 90/90/85 as the goals for NCEA levels 1, 2, and 3 and the 14 plus focus was (developed) at a heads of faculty meeting … we thought it was in the realm of delusion. (Senior teacher, School A, EOP)

By the end of the project, middle leaders were driving goal-setting more and even raising the expectations of what could be achieved in the following year. The change in attitude appeared to be linked to seeing visible success from early efforts; this drove up teacher self-efficacy as the quote from School A illustrates:

I saw the [someone with statistical expertise] and we put together some proposed merit and excellence endorsement targets and then they wanted to raise them—crazy. These same people, and I was one of them, who thought 90/90/85 was out of reach, were now trying to raise the bar which we had already set higher than it was this year. It was astonishing. (Senior leader, School A, EOP)

Justification of goals

The level of staff commitment to the goals appeared to be affected by the justification used by leaders. For example, at School B, staff’s commitment to the goals developed similarly to that of School A. Staff were clear that the goals were to improve writing and behaviour. While staff welcomed the focus on behaviour due to unacceptably high levels of disruption to learning, they were not so enamoured initially with the writing goal. The school had focused on written language for 6 years prior without seeing any improvement, and teachers were tired of it. They saw no issue with current results and felt that the continued focus represented an ongoing critique of their practice.

The turning point came when the principal presented the school’s achievement data in comparison to data from other schools in the area with similar demographics. Staff found the data “an eye opener” (Teacher, School B, BOP) that pointedly showed their overall, highly-performing school to be underperforming compared to similar schools.

Thus, while all schools had narrow and ambitious goals at the beginning of the project, staff did not always feel consulted or involved in setting targets and, initially, they felt pressured by the focus on targets. Data that compared their results to similar schools were successfully used to justify targets, helping staff to see that schools like theirs could perform better.

Goal achievement monitoring

Three major themes emerged related to monitoring: utilising the best data management tools available; using meetings for monitoring; and utilising the concept of “target” or “priority learners”.

Data management tools

Each principal introduced a new data management system to their school almost immediately on arrival to expedite better data analysis. Taking the time to support people to engage with the new tool eventually improved the schools’ ability to track progress. However, the change was not initially welcomed as it represented another task for staff who were already feeling the effects of change that new leadership brings. Many teachers initially thought the expectation that they should engage with data directly was outside the scope of their jobs.

Data-focused meetings

The new data management systems seemed, however, critical for enabling “just-in-time” tracking of students. Comprehensive monitoring and reporting systems were put in place with monitoring occurring at multiple levels, and formal, regularly scheduled meetings being used as the vehicle for monitoring. In the secondary schools, for example, the meetings included:

- tutor teachers monitoring students in their tutor class, with a particular focus on priority learners and reporting to deans

- deans monitoring year groups of students and reporting to senior leaders

- faculty heads monitoring the performance of each of the qualification-level classes in their departments and reporting to senior leaders

- senior leaders monitoring the performance of the “cluster of faculties” they were in charge of, and reporting to the principal

- extended leadership team meetings, involving all of the Senior Leadership Team (SLT) and deans, reviewing all the data with a focus on students who had been designated as “priority” due to both their potential to gain a qualification or endorsement, and risk factors.

Thus, the monitoring system was strengthened by a strong chain of formal and regular reporting: deputy principals (DPs) worked with heads of faculty (HOFs): HOFs worked with department heads; department heads worked with their teachers; and the SLT worked with deans. One HOF described how the lines of accountability became strongly defined through formal, data-based meetings: “I meet regularly with [my DP] and update her on what is happening in [my subject] and then she updates [the principal]. So, there has just been that accountability model I would call it” (School A, EOP). Staff reported that there was an expectation that they bring their data to the meetings and discuss next steps.

The level of improvement appeared linked with the degree of rigour in the systems of meeting and monitoring. Effective practices included:

- having different people in charge of different data sets, creating ownership of the data, and pushing people to have conversations with others when there were issues that needed to be addressed

- having all teachers and leaders reporting results to a specific leader or within a meeting (team, faculty, or senior leadership meeting)

- having principals constantly pushing for teachers and leaders to be creative and to respond to the data about student groups who were not achieving

- using regular meetings as forums for solving problems about what prevented students from making progress.

This approach worked in the primary and secondary schools, but it was less complex in the primary setting because the school was smaller and less departmentalised. Thus, in the primary school—School B—much of the monitoring role fell to the principal and DP who analysed results every term and shared them with staff and senior teachers. The same chain of accountability was evident as in the secondary schools. Senior leaders would review the list of students who had not achieved. The responsibility was then passed on to middle leaders to have discussions with teachers in team meetings. The focus was on what could be done now to impact those results.

Priority or target learners

A third feature of the three schools’ monitoring practices was the use of the concept of “priority” or “target” learners as they variously called them. After 1 year of new leadership at School A, at the beginning of the project, there was already “a much greater awareness of the concept of a priority learner as a learner who requires individualised targeted [and] sometimes quite close levels of scrutiny” (Teacher, School A, BOP). These students were identified as those who could succeed but were at risk of not succeeding for various reasons. The students themselves knew they were “priority learners” and could identify extra support that was afforded them to help them succeed. Throughout the project, the school tightened its systems and focus on priority learners. Deans maintained the focus on these learners in discussions with HOFs and with their teachers: “The deans are more aware, the HOFs are more aware, the teachers are more aware and I think that is pushing priority learners to be more successful” (Teacher, School A, EOP). By the end of the project, School A was starting to move away from school-wide “priority learners” to departmental ones, realising that students were often at risk in different subjects rather than on a school level.

The process at School B was double-pronged. Each teacher identified students they considered were “a target” in their class in the area of the specific goal for the school, which initially was written language. They would inquire into what was problematic for the students’ learning and discuss their strategies with their peers and team leader in regular team meetings. These students were the focus of teachers’ inquiries into their own effectiveness and the subject of very close monitoring in team meetings:

Each teacher obviously knows where their children are at and where they have moved to and what we have done as an inquiry for ourselves to push our target students … and then in our own team meetings we discuss our target students and our inquiry and what we are doing to move them. Then at staff meetings we have discussed it as well and [the principal] reported back any data that has been put in and where we are at and where we want to be and if we are on track and are we going to get there. (Teacher, School B, EOP)

Strategies for school improvement

The strategies for school improvement that were planned by all schools were largely centred on changes to roles, structures, routines, and artefacts; changes to the way the curriculum was delivered; and professional development that was aligned to the goals.

Roles, structures, routines, and artefacts

As can be seen from the previous section, all schools made use of meetings to focus on data about student progress. The extent and rigour of those meetings varied, but they were the key vehicle for holding different members of the school accountable for monitoring progress of groups of students and for having conversations about what to do in response to the data. Other meetings had the purpose of providing leadership. In School B, for example, curriculum teams comprising a representative from the junior, middle, and senior parts of the school formed teams to lead literacy and mathematics across the school.

All schools also changed the nature of people’s roles to increase the focus on tracking progress. The secondary schools changed the role of the deans to have an academic monitoring focus as opposed to a mainly pastoral emphasis, and School B, the primary school, changed the role of team leaders to one of leading joint problemsolving about the progress of “target students” and reporting on it. Previously, these roles had mostly been administrative.

All schools developed and used a range of artefacts to both promote their goal focus and embed practices that would enhance student achievement. A good example of the former is School C’s “Plan on a Page”. It was a concise articulation of the goal, target, and strategies that the school was engaged in; it essentially represented their theory for improvement in a simple and memorable form. The repeated use of it built a high awareness of the goal direction and intended actions to achieve it. School A later also adopted this strategy to clarify direction to staff

Curriculum strategies

All schools also made adjustments to the curriculum in order to reach their goals. The secondary schools reviewed and made changes to what was offered in junior and senior programmes, and how courses should be delivered. There were also changes made to open up entry to subjects to more students in the first year of the project. Some HODs had restricted course entry or used prerequisites such as high levels of attendance as a filter to keep some students out. Changes were made to address inequitable practices such as these. As well as the planned curriculum changes, other practices were put in place by individual HODs or teachers, such as offering extra tutorials to students or filming lessons and putting them online so students who missed lessons could catch up.

All schools used student voice to inform curriculum changes. For example, School B utilised student voice to inform them about how Māori students felt they and their culture were valued in the school. All students were asked about the adequacy of the library. On both occasions, students provided feedback that surprised school leaders and led to concrete changes in practice. As a result of student voice, the school also implemented project-based learning into its curriculum.

In summary, many curriculum strategies emerged from reflection on practices during the course of the project and influenced actions at the classroom level, but these were not always planned up front. They sometimes came as a result of student voice or reflections on the effectiveness of current practices.

Professional development

The three schools’ approaches to professional development in support of the goals varied in many ways but there were some consistent themes. First, they all aimed to raise the leadership capability of their middle leaders by enrolling teachers in leadership courses that would develop their knowledge of their leadership role and the school improvement process. Senior leaders also raised capability by the conversations they had in their own staff or team meetings and through delegation and sharing of responsibilities.

Second, they all used Professional Learning Groups (PLGs) as a vehicle for teacher learning to a greater degree as time went on. These were compulsory in School A, but staff could opt into different groups depending on their interests or needs in the first year of the project. The focus of the groups came out of more generic initial needs, such as developing teachers’ IT skills. By the second year, as a result of the work within the project, staff were consulted about what they could do to impact learning; this resulted in a whole-school focus on the effective use of teacher feedback. PLGs were run by teachers who had upskilled themselves reading research on the topic; the teachers would then provide professional learning sessions to the whole staff at staff meetings. Part of the approach involved teachers recording themselves—not to share with others, but for their own reflection. Teachers also visited others’ classes—not to make formal observations, but to see what they could learn to enhance their own practice. The school’s approach to professional learning appeared to present a coherent approach to impacting teacher attitudes and skills:

We had five … teachers leading these groups where … every other Tuesday [there was] constant talking, discussing, being open, not making teachers feel they are going to be pulled up if they say they are not doing this. (Middle leader, School A, EOP)

The staff that I have talked to have been really positive about those PLGs because it meant that they got to talk across curricula and even this morning when I was talking to a staff member whose results [have] gone from … 60% failure rate to this year 100% pass rate, and she attributes it to the strategies and the ideas that she got given by other teachers of actually how to scaffold the process. (Teacher, School A, EOP)

School B initially relied heavily on expert input at the school level in order to raise teaching capability in written language and to improve behaviour. A provider would come to the school, make observations, and lead staff meetings for written language. A psychologist offered input into remedying the most serious behavioural challenges and the school engaged with an intervention aimed at developing consistent school-wide behaviour management strategies. This degree of focus was a departure from the approach prior to this principal’s tenure: “Prior to [the new principal] we had every new initiative that was floating around … and so it was ‘Let’s try that’” (Senior leader, School B, BOP).

As time went on, they used more internal expertise to implement strategies that would impact across the curriculum, utilising the meeting structures they had put in place. Their team meetings represented their PLGs in which they focused on monitoring progress for target students and staff learning was linked to addressing how they could impact “target learners’” progress.

School C potentially had the clearest communication of professional development strategy. Their “Plan on a Page” outlined their goal (14+) and their three key strategies to achieve that. In the first year of the project, they focused on implementing the new monitoring system, creating an orderly environment and eLearning. This latter focus was required as many teachers had low levels of knowledge about basic computer use, and the school had bought new laptops. By the second year, the focus continued on embedding data monitoring practices for self-review purposes, and moved to improving student agency and accelerating progress of Māori students. PLGs were led and attended by interested staff. Each PLG was aligned to one of the key strategies. Not all teachers were compelled to be part of a PLG, but they had to attend staff meetings that the teachers in the PLGs ran:

The PLG involvement was voluntary but the PD they ran was compulsory. So, you got that choice and I think what was particularly good with PLGs was that they were delivered by a whole range of people [e.g.,] people in their first year of teaching, [or people who] had been in the school for a long time but not necessarily on the leadership [team] and the diverseness of the presentations themselves was quite kinaesthetic and entertaining. Everyone has got their different style of teaching and doing it. (Workshop comment, School C teacher, EOP)

Thus, the professional development in all three schools became more focused on pedagogy as time went on. All schools moved towards more teacher-led professional development and a tighter and sustained focus that would impact pedagogical practice by the second year of the project.

Collective responsibility

The key questions that arose for all schools as they focused on improving outcomes or the equity of outcomes, were: How do you create staff buy-in to goals and strategies? How do you build collective responsibility and internal accountability for results whilst building trust? The principals attempted to build collective responsibility with two key strategies, though they were not limited to these and these were not necessarily strategies they planned in advance: driving responsibility and accountability “down” to middle leaders by role change and respectfully challenging others’ point of view about not taking responsibility; and creating teacher-driven teams.

Driving responsibility down

Firstly, all principals were very clear about their goal focus and their desire to push responsibility for student achievement down to middle leaders and teachers. In all schools, principals immediately changed responsibilities of both senior and middle leaders so that their previously mostly administrative roles included a strong focus on student achievement data, as discussed in the monitoring section earlier. The assumption that data use was a job for everyone was not necessarily well received:

I am not a statistician yet I am asked to collate, analyse, and interpret data. Can we get people with time and expertise to do this so we can teach? (Middle leader, School A, middle of the project)

Many middle leaders and teachers found the principals’ level of challenge to any “push back” about that responsibility confronting:

So, the one I remember really clearly is the dean when we were talking about attendance of a student and I said, ‘Well, okay, that is the problem. What is the solution to this?’ and she talked a bit more about the problem. So I said, ‘Okay, that’s the problem. What is the solution to this?’ and I had to say it three times and then she said, ‘Well, that’s not my job.’ So, challenging those moments when actually it is all of our jobs to find the solutions to the problems because if it is only one person then that is no good. (Principal, School C, EOP)

These very direct challenges to staff pushed people to take responsibility and had both positive and negative impacts. On the positive side, many teachers seemed to take more responsibility for outcomes:

We have become so much more aware of being responsible, accountable for their overall physical, emotional, educational wellbeing. We have become more aware of that and I think when you become aware you become more accountable and I think a lot of staff have become more aware than they were before and a lot of staff have stopped blaming it on 10,000 things on why they aren’t meeting the targets. (Teacher, School A, EOP)

Staff felt the pressure of accountability that would occur in upcoming scheduled meetings, but as time went on staff moved from an attitude of compliance, to one of acknowledging that the examination of data was integral to their work:

I think the accountability, you know your turn is going to come so you have to front up with something and we encourage them to bring the books as well so … the evidence is there. I guess the culture has changed; that it is no longer seen as compliance. Most teachers will see it as something helpful, it helps the person who is sharing, but it also helps others because they all think ‘Oh maybe I could try that.’ (Senior teacher, School B, EOP)

Even, though this focus may have been resented by some initially, seeing the results of their hard work come to fruition seemed to turn people’s attitudes:

So, when there is something really exciting happening, [and] they know that there is a shift, you know, like the boy/girl thing [meaning getting more equitable results], the balance shifted quite dramatically and that is quite affirming. So people have taken risks and done things they didn’t necessarily believe in or want to do but they wanted to make a difference. So, they had a go and they see some quite good shifts. (Teacher, School B, EOP)

Thus, driving responsibility “downwards” to middle leaders and teachers meant there was inevitably some push back but, ultimately, positive results started to improve teachers’ sense of collective responsibility.

Teacher-driven teams

Secondly, the strategy of creating teacher-driven teams seemed to have a positive impact on collective responsibility in all schools. By the end of the project, the secondary schools’ teacher-led PLGs were being very positively reported on. The success of the strategy was largely attributed to the teacher leadership of them. Teachers reported not feeling judged and that the PLG genuinely focused on teachers’ and students’ needs.

The focus on pedagogical changes was sustained over the whole year and allowed teachers to talk frankly without feeling judged. The consequent raising of results in some departments or classes made at least some teachers converts to the espoused good practices.

School B purposely created cross-school curriculum teams to lead curriculum areas. While they had strong associations with teachers in their year-level teams (junior, middle, or senior school), these curriculum leadership teams comprised a teacher from each of those year-level teams which helped to shift the culture from one where staff only focused on their area of the school to one where they had to think about the impact of actions on the whole school. The principal also purposefully mixed teachers up in staff meetings in a concerted effort to change dynamics and to move the sense of team to the whole-school level.

Many staff attested to the sense of teamwork and collaborative responsibility that developed as a result of these changes:

It has brought us together as a school more, but we are also all working on that goal together. It has just been more collaborative; we want our children to be collaborative so we, the staff, have to be more collaborative for them to do it as well. I think the fact that we are discussing it more at staff meetings—where we are going and where we are at, and where we want to be at. (Teacher, School B, EOP)

Building trust

Part of creating collective responsibility in schools is building trust between leaders and staff. It appeared that trust was built in the schools due to: leaders being authentic and making themselves vulnerable at times; and leaders developing tight team work.

All principals spoke about authenticity and demonstrated their willingness to make themselves vulnerable by owning up to their own mistakes or concerns to staff. The principals used the feedback they received as a result of the case studies of their schools at the beginning of the project as data to share with staff and to acknowledge where things were going wrong. For example, the principal of School B acknowledged to staff that success relied on more than putting the procedures in place, which she had concentrated on initially, and she used the feedback she received at the beginning of the project from this project’s confidential interviews with her staff as evidence to acknowledge and act on:

I think by going through the interview results and sharing with my staff was the start of my shift of school culture really and [being] open and honest and vulnerable and putting it out there and me realising that actually you can have the clinical stuff in place, you have got to have the right culture to go with it and that takes constant work. (Principal, School B, EOP)

Similar comments were made by the others, with the principal of School C explaining that improving trust took a lot of purposeful action:

Being authentic, owning up to when I made mistakes, building interpersonal respect and regard and sitting down and having very clear, concise meetings when something goes wrong. (Principal, School C, EOP)

The principal of School C’s way of dealing with challenge was to “praise in public” and “debate in private”:

… we don’t have to say how wrong things are going in public. You can do that one to one in a respectful conversation and be positive about the changes that are happening in public. (Principal, School C, EOP)

Secondly, all the principals commented on the importance of team work with other members of their SLTs. They all appointed at least one new person into a senior role but the principal in School C also commented on the importance of tapping into the knowledge of someone who knew the school well:

So that is another aspect—being a really strong, tight senior leadership team where we can discuss we have got each other’s back. We are all on board with those and I think X (senior leader) has been a really big help with that because she is someone who has been here for 30 years and she has been on board with the changes and I think that has made a significant difference. So she can span that gap between how things have been so keeping that strong traditional values that the school had while still moving it forward.

Overall, the tension could be seen between developing accountability for results and developing collective responsibility and trust.

Did principals’ goal-setting practices improve equity in student outcomes?

While it is impossible to show causal links between the strategies put in place and results, the schools made a visible impact on equity of results over the 2 years. Some of their achievements noted below attest to the successes of the schools. Our overall conclusion was that the stronger the monitoring, the better the results.

School A had raised achievement in NCEA markedly in the principal’s first year at the school (2017); 1 year prior to the beginning of the project. The school continued with its focus on high targets (90/90/85 for NCEA Levels 1–3) throughout the project. While it did not always achieve these targets in each level, its achievement was markedly higher than the national average and the average of schools in the same decile band in all 3 years (see Table 1). Achievement was also markedly higher than it had achieved previously (e.g., in 2015–16 it achieved 71%–78% in NCEA Level 1 and 79%–84% in Level 2, and around 60% in Level 3).

Halfway through the 2-year project, the school added another focus on raising endorsements. The percentages of students receiving Merit increased between 4% and 8% from 2017–19 in NCEA Levels 1–3, and the percentages of students receiving Excellence increased by about 9% in NCEA Levels 1 and 2. In the last year of the project (2019), the school added University Entrance as a key focus. In 2019, its results were 11–15 percentage points higher than the national average and 21–35 percentage points higher than average achievement in decile 1–3 schools.

| Qualification | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 Nationally |

2019 Deciles 1-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 89.5% | 85.5% | 80.3% | 69.3% | 55.1% |

| Level 2 | 92.4% | 92.6% | 89.2% | 76.6% | 67.0% |

| Level 3 | 76.2% | 74.2% | 82.4% | 66.2% | 57.5% |

| University Entrance | 48.8% | 45.9% | 63.3% | 47.8% | 27.6% |

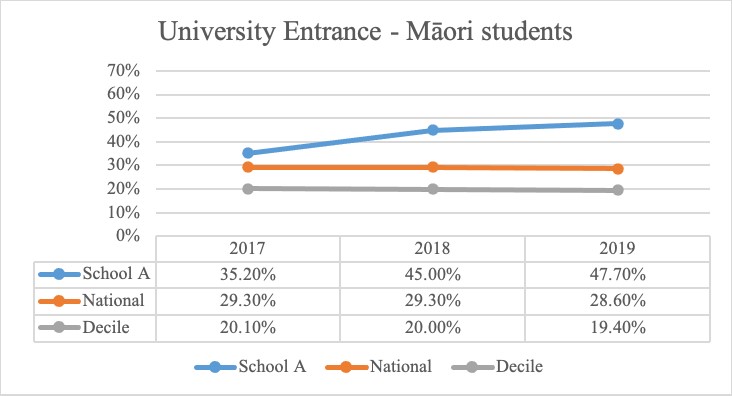

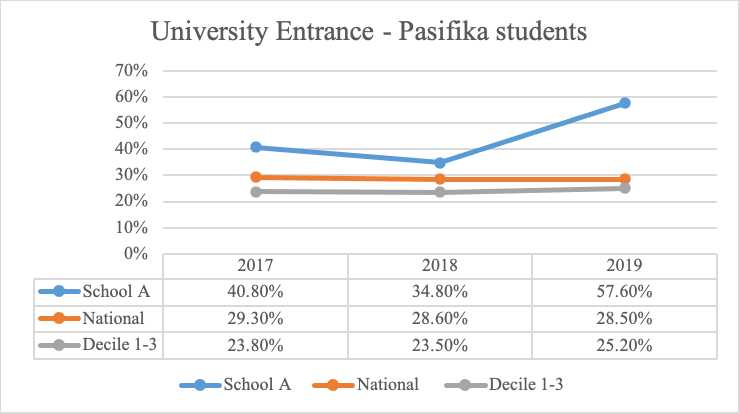

With a view on equity, School A focused on raising the number of Pasifika and Māori students achieving University Entrance, especially in the last year of the project (2019). As can be seen in Figures 2 and 3, School A achieved this goal for both student groups.

FIGURE 2 University Entrance achievement—Māori students at School A

FIGURE 3 University Entrance achievement—Pasifika students at School A

The other secondary school (School C) struggled to maintain the 2017 achievement and saw a drop in Levels 1 and 3 and University Entrance over the course of the 2 years in the project, only maintaining achievement levels at NCEA Level 2 (see Table 2). At all levels, the school was below the national and decile levels of achievement. One reason for the drop was the abolishment of summer school at the end of the school year prior to the start of the project, where students could achieve a few final credits in order to pass their NCEA qualifications. The school wanted students to make the gains during the year; not through catching up. Another reason the school acknowledged was that data monitoring was not tight enough throughout the year.

| Qualification | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2019 Nationally |

2019 Deciles 1-3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | 70.4% | 49.1% | 52.6% | 69.3% | 55.1% |

| Level 2 | 60.6% | 56.2% | 60.1% | 76.6% | 67% |

| Level 3 | 62.6% | 72.6% | 50% | 66.2% | 57.5% |

| University Entrance | 11.1% | 11.3% | 7.1% | 47.8% | 27.6% |

In regard to increasing equity in outcomes, the school added a particular focus on increasing Māori students’ achievement in 2019. A lift in NCEA Level 2 was evident. However, the school serves only a small number of Māori students, with the 58.8% passing NCEA Level 2 in 2019 representing 10 Māori students.

School B focused on eliminating disruptions to learning and raising achievement for boys in writing. For behavioural incidences, one indicator was stand-downs, with the numbers of stand-downs going from two in year one, to one in the subsequent year, and none in the last year of the project. It also recorded behavioural incidents but the criteria for recording these changed over the course of the years, so the numbers are more difficult to interpret. In 2017, it recorded 273 major “incidents” which reduced to 196 in 2018. But, in 2019, it started recording minor incidences as well, thus the numbers rose again to 258. Staff reported that behaviour had improved markedly and noted a calm environment where classroom disruptions were unusual.

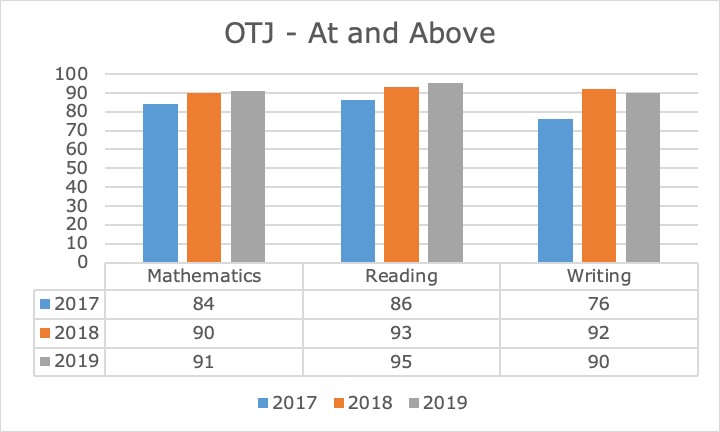

The school made improvement in all three core subject areas—reading, mathematics, and writing (see Figure 4). The focus on written language resulted in a major shift in results after the first year that was sustained in the second year. Although it was not a key focus, reading results improved with the written language results. The school moved to a focus on mathematics half way through the project which also resulted in discernible improvements.

FIGURE 4 Proportion of students receiving Overall Teacher Judgments (OTJs) of at and above standard in mathematics, reading, and writing at School B

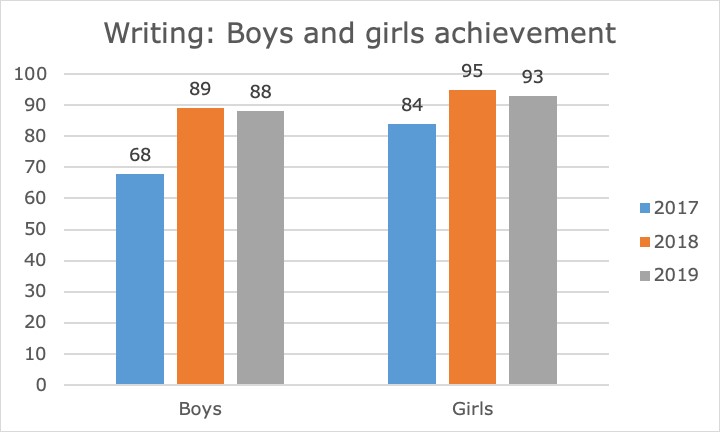

From an equity perspective, there was a particular emphasis on raising the results of boys in writing. This focus on inquiring into barriers for boys resulted in a large improvement in the principal’s first year at the school and these results were sustained in the second year (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 5 Proportion of boys and girls receiving Overall Teacher Judgments (OTJs) of at and above standard in writing at School B

Implications for practice: School teams

Both the academic and the school-based teams learnt a considerable amount about the practical work of improvement through this project. This learning is briefly discussed with a focus on school teams first and then consideration of implications for the academic team if they were to undertake a similar project in the future.

Memorability of goals or targets is not enough

While previous research (Bendikson et al., under review) has highlighted the need for senior leaders to be very familiar with their goals or targets, this project illustrated some nuances in this regard. In School A, targets were added over time. The increased number of targets did not seem to have detrimental effects on the school’s goal focus and achievement, even though people could not articulate what the more recent targets were. What all schools had in common was that they had clear goals—they knew what they were working on to improve (e.g., written language or University Entrance). School C had one very clear and memorable target, but that in itself was not enough to motivate the required degree of collective action. It was the structures, procedures, and habits that the schools formed in the way it worked with data that appeared to impact most.

Developing new habits of data-use initially requires strong lines of external accountability

The value of routines in well-managed meetings that focused on data and the implications of that data, was self-evident from these schools’ results. Their success was most tightly related to their rigour in monitoring throughout the year. It seemed the sustained and unrelenting focus on monitoring and problem-solving was what made the difference. Where this occurred, internal accountability and collective responsibility appeared to develop only after these processes helped the schools to get better results. Collective responsibility appeared to result from raising the level of teacher and leader efficacy, which in turn resulted from their implementation of data-based practices which, initially, were not welcomed.

Some key leadership actions that contribute to improvement—goal focus

The school leaders all agreed that some key behaviours on their part, were most impactful:

- Keep goals simple, clear, and have only a few.

- Be transparent about why these are the goals—share the reasoning.

- Revisit goals often.

- Share and create discussion about the data: What do you see? What do you think the causes are?

- Retain a long-term focus—do not be constrained by one year to reach a goal.

Some key leadership actions that contribute to improvement—strategies for improvement

- Assign specific people to have oversight of specific targets or data sets.

- Allow flexibility about how to achieve the goals (e.g., working at the junior level may differ from the senior level).

- Utilise meetings to monitor data and problem-solve about next steps.

- Develop a strong SLT–middle leadership culture of shared problem-solving through joint meetings.

- Create visible accountability for results through regular and formal reporting of results.

- Design PLD that increasingly becomes teacher-led and cross-curricula or cross-team.

Implications for practice: Academic team

The academic team also reflected on the process we have undertaken, and, finally, we summarise changes we would make in the future if we had a similar opportunity again:

- Have a broader collection of perspectives across the schools at the beginning and end of the project such as a questionnaire to all staff.

- Have a stronger impact at the beginning for the project on the schools’ planning for the first year of the project. The feedback we gave after the initial case studies was powerful but was provided in March of the first year and the timing meant it could not influence the planning for that year. We were constrained by TLRI funding timing, but we should aim to start in November the year prior if given another opportunity.

- We should have gathered data on behavioural issues at the beginning of the project; schools did not have systematic ways of gathering these data even though they reported issues, and while schools reported clear improvements, we could not quantify the degree of this impact well. Again, this could be addressed by working with the schools from term four, prior to the funding for the project, to identify key goals and ways to measure progress.

Conclusion

The project has had an immediate impact: it has increased the leadership capabilities in the participating schools and supported their focus on improving outcomes for learners. It has also highlighted the critical role of principals in leading the pursuit of more equitable outcomes and painted a clear picture of some of the practices that impacted most. Further, it has increased our working knowledge of how to support schools to improve outcomes. We hope this project will provide succour to principals who bravely push for the outcomes their students deserve.

References

Bendikson, L., Broadwith, M., Zhu, T., & Meyer, F. (under review). Goal setting behaviour in secondary schools: Hitting the target? Journal of Educational Administration.

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Harvard Education Press.

DuFour, R., & Mattos, M. (2013). How do principals really improve schools? The Principalship, 70(7), 34–40.

Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (1998). Exploring the principal’s contribution to school effectiveness: 1989–1995. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 9(2), 157–191.

Latham, G. P., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Enhancing the benefits and overcoming the pitfalls of goal setting. Organizational Dynamics, 35(4), 332–340.

Leithwood, K., Seashore Louis, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. The Wallace Foundation.

Robinson, V. M. J., Lloyd, C., & Rowe, K. J. (2008). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: An analysis of the differential effects of leadership types. Education Administration Quarterly, 44, 635–674.

Timperley, H., Kaser, L., & Halbert, J. (2014). A framework for transforming learning in schools: Innovation and the spiral of inquiry. Centre for Strategic Education.

Project team

Dr Frauke Meyer, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland. f.meyer@auckland.ac.nz

Dr Linda Bendikson, LB Schooling Improvement. l.bendikson@gmail.com

Associate Professor Deidre LeFevre, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Auckland. d.lefevre@auckland.ac.nz

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the principals who showed their trust in us and made themselves vulnerable through their involvement in this project. They worked closely with other leaders and teachers in their schools to discuss progress across the 2 years and were open to feedback from both them and from the academic team. Their willingness to consider a range of views and to both inquire into other ways of working and to advocate for ways they were committed to, were admirable. They are indeed lead learners.

To their project teams, we also offer heartfelt thanks. Some commented that it was a unique opportunity to sit and have an open dialogue with their principal outside of school in ways that are hard to replicate inside schools. This was valued greatly by them and helped staff develop a deeper understanding of the challenges the principals faced as well as giving them an opportunity to advocate views that differed from those of their principals. Finally, to TLRI we offer our sincere thanks for this opportunity to support improvement in schools and to learn along with our colleagues.