Introduction

Our approach to research intentionally engaged processes of co-design whereby the study of pepe meamea (Samoan conceptualisation of infants and toddlers) with our research partners ensured that the values and practices of Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems were privileged throughout all stages of the research. The co-design process we collectively premised affirms relationality that grounds both collective and individual engagement within and contributions to the study. The 2-year project focused on reconceptualising and transforming the pedagogy of early childhood education (ECE) teachers of Samoan infants and toddlers into sustainable and holistic approaches to improve ola laulelei (cultural wellbeing) outcomes for Samoan infants and toddlers. From a Samoan perspective, ola refers to holistic life/living and laulelei refers to being in balance (Sililu, 2021).

Samoan intergenerational practices were embedded through Samoan cultural mentoring partnerships between teachers of infants and toddlers from Aoga Amata (Samoan full-immersion and bilingual) and their counterparts in English-medium ECE centres in Auckland, supported by Samoan cultural experts. Samoan onto-epistemology (Matapo, 2021a) and postqualitative research approaches (Murris, 2020; St Pierre, 2015) informed the research design and process, affirming Samoan Indigenous knowledge by engaging the research community in culturally sustaining pedagogies (Paris, 2012) through dialogue, embodied practices, and innovation of Samoan conceptualisations within the context of ECE.

This report opens with a brief description of the research. This is followed by a discussion of the methodological considerations that position the research within Samoan onto-epistemology alongside postqualitative research methods, both of which are defined in that section. Postqualitative research is an approach that challenges conventional qualitative methodologies and engages research processes through non-linear, complex networks of meaning-making and emergent practices. The positioning of this research was intentional and emphasised the value of relationality and the importance of dialogue and engagement between different knowledge systems. The combination of Samoan onto-epistemology and postqualitative methods enabled the co-creation of knowledge through the fostering of intercultural dialogue, collaboration, and mutual learning. Following these sections is a mapping of the demographic landscape of the Samoan population within Aotearoa and the significance of strengthening Samoan pedagogies in ECE for the ola laulelei of Samoan New Zealand-born tamaiti (children). The report posits an Indigenous reference for Samoan pedagogies in ECE through a vā relational ethos (Anae, 2016) that includes Samoan cross-cultural mentoring relationships between faiaoga (Samoan ECE teachers) and English-medium ECE teachers.

Description of research

The aim of this research is to develop a Samoan pedagogical framework for educating and enriching the ola laulelei of Samoan pepe meamea that can be mobilised within Samoan ECE settings as well as Englishmedium ECE contexts. The research leads are Jacoba Matapo, Fa’asaulala Tagoilelagi-Leota, and Tafili Utumapu-McBride, all of whom are Samoan. Together, they hold more than 70 years’ experience in Pacific ECE. This research project draws upon not only their experience in ECE and initial teacher education but also their extensive ECE sector and community networks. The focus of the study, deeply rooted in the research team’s positionality, is to Indigenise infant and toddler pedagogy for the cultural wellbeing of Samoan pepe meamea within Aotearoa.

The emphasis of the pepe meamea framework is on embedding Samoan knowledge systems and practices conducive to the cultural wellbeing and belonging (Mara, 2013; Ministry of Education [MoE], 2017) of Samoan infants and toddlers. As an indigenous-based ECE study that takes a unique transnational Samoan position, the research aims to contribute to ECE scholarship in both Aotearoa New Zealand and Samoa. The 2-year study engaged Samoan and non-Samoan teachers of Samoan infants and toddlers through cross-sector partnerships. In the first year of the study, Samoan conceptualisations and philosophy of pepe meamea were explored, which led to the development of a Samoan glossary with 89 Samoan concepts inspired by Samoan onto-epistemologies of pepe meamea. In the second year of the study, Samoan teachers, Samoan elders (knowledge custodians), and non-Samoan teachers were involved in learning, alongside researchers, specific holistic Samoan pepe meamea concepts and practices to refine, activate, and transform their practice within their teaching of pepe meamea.

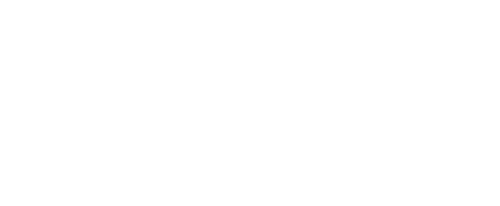

The following section presents the pepe meamea pedagogical framework as an entangled, interconnected concept with the potential to evolve, adapt, and advance through ongoing engagement with Indigenous knowledge systems grounded in relational and embodied practice.

Methodological considerations: Prioritising Samoan onto-epistemologies

Samoan cultural knowledge custodian and former head of state Tui Atua (2005) outlines a range of tensions underlying Samoan Indigenous knowledges. He regards Samoan knowledge as challenging to conceptualise due to its relationally ontological positioning, which posits that we are what we are because of our relations with other entities, such as time and space, earth, skies, oceans, and the cosmos, that are corporeal and incorporeal (Matapo, 2021a). Samoan onto-epistemology informed the research to encourage a more inclusive approach to knowledge production, valuing the contributions of Samoan communities’ diverse voices and the influence of Samoan material worlds and discourse (Matapo, 2021b). Onto-epistemology contests the hierarchal separation between the human and non-human worlds (Matapo, 2018). Furthermore, onto-epistemology helps challenge and disrupt the hegemonic power structures that have historically marginalised Indigenous peoples and their knowledge systems (Matapo, 2021b). Through his scholarship, Tui Atua conceptualises the process of Samoan thought and its relationship to Samoan cosmogonies and the world, as composed of spiritual, ecological, cultural, and social spheres of knowing (Tui Atua, 2005, 2009, 2017). According to Tui Atua (2005, 2009, 2017), the movement of knowledge is never static: it generates new connections. Furthermore, embodied knowledge in and with the world is tied through relational ecologies (Matapo & McFall-McCaffery, 2022; Tui Atua, 2005). Critical factors influence the ability to sustain Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems, including the change and flux of migration, cultural shifts in local society, the internalising of colonisation, and the penetrating forces of capitalism and neoliberalism upon Samoan epistemologies (Anae, 2016; Matapo & McFall-McCaffery, 2022; Muaiava, 2022). For transnational Samoan communities engaging in Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems away from ancestral lands, limited access to the learning of Indigenous knowledge and language loss has adverse implications (Matapo, 2021b).

The study drew from Samoan onto-epistemology to inform all phases of the research, including the research co-design process and analysis, in order to encourage a more inclusive approach to knowledge production that values the contributions of diverse voices within Samoan communities as well as the influence of Samoan material worlds and discourse (Matapo, 2021b). Onto-epistemology contests the hierarchal separation between the human and non-human worlds (Matapo, 2018). Furthermore, onto-epistemology helps challenge and disrupt the hegemonic power structures that have historically marginalised Indigenous peoples and their knowledge systems (Matapo, 2021b).

The following section introduces the research methodology of talanoa, postqualitative inquiry, and the accompanying lalaga (weaving) practices utilised within the study. Postqualitative inquiry, conducted alongside Indigenous philosophy, confronts the tendencies of humanist thought to depend on a humancentric measure for meaning-making in the world. Postqualitative inquiry disrupts the ways we do research by questioning assumptions to enable new ontological research approaches to emerge. As Samoan researchers, the selection of talanoa methodology (described below) supports the ethos of the research, in that it culturally affirms Samoan ways of knowing and co-construction. Our approach to co-design foregrounds the Samoan values and practices that are privileged throughout the research. As Samoan researchers, we approach the co-design of research as a “lived”, co-constructed and co-agentic process that affirms relationality within the study. Such research prioritises tausi le vā (taking care of relational spaces), which generates a connection between cultures, knowledges, the world, and tagata (people/person). While connections made through the relational practice of talanoa may include traces of the familiar, vā also holds a space for differences to be present.

Talanoa and lalaga (Samoan weaving)

When translated, the Samoan word “talanoa” or “talanoaga” means to talk, share stories, inform, and dialogue (Matapo & Enari, 2021; Vaioleti, 2006). The generative capacity of talanoa lies within its emergent yet culturally sustaining condition(s) for the co-creation of knowledge and understanding. The holistic and relationally grounded practice of talanoa encourages the potential for novel and varied ways of thinking with Pacific Indigenous philosophy (Matapo & Enari, 2021). Vaioleti (2006) explains that the cultural practice of “talanoa is mostly oral and collaborative and is resistant to rigid, institutional, hegemonic control” (p. 24). This means talanoa can be used as relational practice (Matapo & Enari, 2021) to activate a collective political space of resistance in which we can safely dialogue through pressing issues and challenges in our hearts and minds. Conceptually, incorporating talanoa into the research process challenges binary oppositions by holding space for differences in our experiences of relating to each other and the world.

Another layer of Indigenous research practice entangled with talanoa that this study explores is the process of lalaga (Samoan weaving). To bring together teachers, researchers, elders, and weavers as part of the talanoa assemblage, research events included lalaga with Samoan weaving experts and cultural knowledge custodians was part of the research events. The engagement of lalaga was incorporated within research phases one (with faiaoga/Samoan teachers) and two (with faiaoga and ECE teachers).

Engaging in both lalaga and talanoa generated different modes for meaning-making between intergenerational voices, hands, and material (the pandanus leaves). Through lalaga and talanoa, the intricate multiplicities of collective meaning-making were conceived and reconceived, with human and non-human worlds coming together (Matapo & Enari, 2021). The leaves used for lalaga were prepared in Samoa; a whole village had been involved in the stages of lalaga preparation. When ready, the laufala (pandanus leaves) were shipped to Aotearoa New Zealand, through Falelalaga Village (House of Weavers), a Samoan community organisation supporting the revival of Samoan weaving in New Zealand for the benefit of Samoan communities. Falelalaga Village, as a community organisation, was already known to the researchers, but the weavers from this group who joined in the lalaga sessions were not known to the faiaoga or the researchers. From a Samoan onto-epistemological perspective, it is evident that the embodied and relational engagement within this project extends beyond the immediate “peoples” and cultural materials embedded within the project. The leaves, the many hands (from Samoan villages), the soil, the history, and the genealogies from the Samoan villages that sourced the laufala were entangled within the talanoa weaving events.

Contextual factors: Background

The majority of Pacific people living in New Zealand today are New Zealand-born. The highest proportion of all Pacific peoples in New Zealand are Samoan (48.7%) who are primarily New Zealand-born (Ministry of Social Development, 2016; Statistics New Zealand, 2013). Most of the Samoan-New Zealand population lives in Auckland (65%). Although gagana Samoa (Samoan language) is the third most common language spoken in New Zealand, only 44% of New Zealand-born Samoans are proficient in gagana Samoa (Ministry for Pacific Peoples, 2020). The maintenance of the Samoan language within ECE has been supported through community and collective efforts of Aoga Amata (Samoan full immersion ECE centres) for over 35 years. The first Aoga Amata was established in Wellington in 1987 with the specific purpose of grounding the Samoan language, culture, and spirituality in the fostering of the wellbeing, identity, and culture of Samoan children (Ete, 2013).

The abundance of international ECE discourse gives prominence to Eurocentric notions of infant and toddler development and pedagogy, and there is very little attention in research to Pacific ethnic-specific philosophy and pedagogy for infants and toddlers (Rameka & Glasgow, 2015; Rameka et al., 2017). In New Zealand, the majority of Pasifika children (including Samoan) are enrolled in English-medium ECE centres (MoE, 2015). A concern raised by transnational Samoan scholars is that infant and toddler pedagogies adopted within ECE are not always conducive to Samoan collective understandings of “being” and personhood, which shape the foundation for their wellbeing, belonging, and identity (MoE, 2017; Tagoilelagi-Leota, 2018; Toso & Matapo, 2018; Utumapu-McBride, 2013).

Unsurprisingly, international ECE discourse continues to penetrate New Zealand-based research into dimensions of education philosophy and teaching from birth to 5 years (Leaupepe et al., 2017). An influx of literature in the new millennium remains transfixed on the “infant and toddler” as representing universal phases of development and gives little attention to Pacific philosophy (Tagoilelagi-Leota et al., 2022). A broad literature review on quality ECE for under 2-year-olds (Dalli et al., 2011) did not identify Samoan pedagogies as an indicator for pepe meamea.

Because there have been so few Pasifika ECE research projects on the subject of infant and toddler pedagogy targeted to either one or several Pacific-specific ethnic groups (Rameka & Glasgow, 2015; Rameka et al., 2017), this research took up a unique collaborative approach to engage cross-sector partnerships. In this study, experienced Samoan ECE teachers, as cultural experts, supported and mentored non-Samoan ECE teachers in the spirit of enhancing and sustaining cultural pedagogies that affirm Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems (Koya-Vaka’uta, 2017). Partner ECE centres within the same community were matched to strengthen local professional learning partnerships and to generate an extended community of inquiry (Davis & McKenzie, 2017). This research intends to inform future directions for infant and toddler pedagogy in ECE, given the steady growth of the Samoan New Zealand-born population, which reportedly increased by 27% between 2013 and 2018 (Ministry for Pacific Peoples, 2020) and can be expected to continue to rise.

Research questions

Phase one research questions (specific to the Aoga Amata ECE context):

1) What is pepe meamea, and how is it grounded in Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems and ontology?

2) How is pepe meamea pedagogy understood and practised within Samoan Aoga Amata communities?

Phase two research questions (relevant to Aoga Amata and ECE centre partners):

3) How effective are cross-cultural mentoring partnerships between Samoan Aoga Amata and Englishmedium ECE centres in fostering culturally sustaining pedagogies through the Indigenous Samoan framework of pepe meamea?

4) How has teacher engagement with Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems and the framework of pepe meamea transformed pedagogy to enhance the ola laulelei (cultural wellbeing) of Samoan infants and toddlers?

Phase one

In the first year, the research collaboration and partnership included six Aoga Amata centres in the Auckland region (see Table 1). Phase one of the project targeted Aoga Amata engagement in recognition of the cultural expertise, gagana (Samoan language), knowledge, and experience that Samoan infant and toddler faiaoga carry; faiaoga were engaged as co-leaders of the process of developing a Samoan pedagogical framework for Samoan pepe meamea. Key staff of the Samoan full-immersion ECE centres already knew each other through longstanding relationships with SAASIA (Samoan Aoga Amata Society in Aotearoa), representatives of which were also consulted in the initial design of the research and proposal. In the first year, 28 faiaoga across all six Aoga Amata were involved in the research; included were under-2 faiaoga, team leaders, and some over-2 faiaoga. The criteria for participant selection included all centres (Aoga Amata and English-medium ECE) having Samoan infants and toddlers enrolled. All research fono (meetings) were hosted locally at Auckland University of Technology Manukau campus and were designed for the participation of faiaoga, teachers, and staff of the participating Aoga Amata. The researchers engaged in multiple roles during each research fono. Researchers facilitated talanoa and engaged in learning lalaga and cultural practices alongside faiaoga and teachers; they also were responsible for documenting, observing, audio recording, and photography.

| Aoga Amata ECE centres (year one) |

|---|

| Seugagogo Aoga Amata (full immersion Samoan) |

| Fotumalama Aoga Amata (full immersion Samoan) |

| Taeaofou i Puaseisei Preschool (Raglan Street) (bilingual Samoan) |

| Fetu Taiala Aoga Amata (full immersion Samoan) |

| Tumanu Ae Le Tu Logologo Aoga Amata (full immersion Samoan) |

| Taeaofou i Puaseisei Preschool (Winthrop Way) (bilingual Samoan) |

Of the six Aoga Amata, two have been established since the inception of Pacific ECE centres in New Zealand in the late 1980s; these centres are Seugagogo Aoga Amata and Tumanu Ae le Tu Logologo Aoga Amata. Seugagogo Aoga Amata is the only Samoan ECE centre in the suburb of Otahuhu, which operates under the Ekalesia Faapotopotoga Kerisiano I Samoa/Congregational (EFKS) Christian Church of Samoa Otahuhu. Most of the faiaoga are from the church. Tumanu Ae le Tu Logologo Aoga Amata is another pioneering ECE centre under the management of the Pacific Islands Presbyterian Church (PIPC) in Papakura. The faiaoga composition of this Aoga Amata are mainly qualified teachers from the church. Fetu Taiala Aoga Amata is located in Mangere and has been operating since the 1990s. Fotumalama Aoga Amata operates within the premises of the Manukau Samoan Methodist Church. The remaining two ECE centres, Taeaofou I Puaseisei Preschool (Raglan Street) and Taeaofou I Puaseisei Preschool (Winthrop Way), are new ECE centres under the EFKS Mangere East Church. These Aoga Amata serve the members of their communities, some of whom are not Samoans, which explains the bilingual delivery medium of both ECE centres.

The research fono involved a mix of mature and young faiaoga from each Aoga Amata, who range in age from 25 to 65 and vary in language proficiency: Samoan is spoken fluently only by the older faiaoga. The Aoga Amata (full immersion Samoan ECE centres) is comprised of faiaoga who have all taught for 30 plus years, while the two Samoan bilingual ECE centres include faiaoga who have 6 to 15 years of teaching experience. Some of the older faiaoga were born and raised in Samoa, while the younger faiaoga were born and raised in New Zealand. It is fair to say that the project further strengthened the confidence of the New Zealand-born faiaoga in talanoa and personal cultural identity.

All six Samoan ECE centres are attended by children from their respective churches and neighbouring Samoan communities. The preference among parents is for their children to transition to Samoan bilingual classrooms in a nearby primary school for continuity of access to Samoan language in their learning.

Prior to the first research fono, participating faiaoga from six Aoga Amata in Auckland were introduced to the project and the co-design process, and a discussion was held around the project ethics and consent. At the first research fono, an initial questionnaire was provided to scope faiaoga conceptualisations of pepe meamea. During this fono, faiaoga engaged in talanoa (Kolone-Collins, 2010; Vaioleti, 2006) and were invited to share any specific cultural stories/experiences of pepe meamea. Childhood stories emerged, with specific references to village and aiga (family) practices and experiences of cultural conventions relevant to their teaching. The first research fono prioritised vā (relationality) (Matapo & McFall-McCaffery, 2022) between Aoga Amata centres, encouraging cross-centre collaborations and undertaking a co-design process to inform the directions of subsequent research fono.

Across all four research fono in the first year, gagana (Samoan language) was the main language utilised, which facilitated deep connections to Samoan Indigenous knowledge of pepe meamea. Through gagana Samoa, our faiaoga came together to theorise personal and professional practices and understandings of Samoan subjectivity, wholeness, spirituality, and being for Samoan infants and toddlers. Combined with the four fono events, there was an integration of online fono, which supported the ongoing sharing, communication, and reflection on their practice between all members of the study. The online talanoaga (Samoan for ongoing conversations and dialogue) supported relational practices across different Aoga Amata contexts and communities through a digital vā (online relational space) presence (Enari & Matapo, 2020; Koya-Vaka’uta, 2017). Talanoa was exercised frequently throughout the study as a relational praxis and was at the heart of all teacher and researcher interactions, meaning that conditions to engage fluidly in talanoa were encouraged throughout, either face to face or virtually, via the online research platform (Anae et al., 2001).

Through research fono two, three, and four, faiaoga reported the significance of utilising the gagana to conceptualise complex Samoan concepts of pepe meamea. Faiaoga reported that the deficiency of English translations made it difficult to both interpret Samoan terms into English and apply Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems to curriculum and policy changes to improve teaching practice for pepe meamea. During fono two and three, faiaoga co-led the development of a Samoan pepe meamea glossary of conceptual and pedagogical terms, which ultimately included a total of 89 terms. This glossary of pepe meamea terms was frequently revisited, utilised, and critiqued by faiaoga and research partners through ongoing talanoa and reflection.

Research fono four was organised as a lalaga community event, bringing faiaoga and Samoan master weavers together to engage with a traditional practice of lalaga of fala pepe (baby mats). This lalalga event aimed to satisfy faiaoga aspirations to “awaken” a vanishing traditional pepe meamea practice. Faiaoga and cultural experts reported that, in the contemporary context, the fala pepe weaving and gifting ceremonies are not as common across Samoa. From the fala pepe lalaga event, the development of the pepe meamea pedagogical framework emerged.

Through the first year, faiaoga grew comfortable sharing cultural knowledge, even engaging their sense of humour while examining Samoan terms to support the transformation and enhancement of their cultural pedagogies. The significance of face-to-face interactions during this research period was critical, as frequent COVID interruptions meant that faiaoga were affected socially, culturally, and professionally. Disruption to scheduled face-to-face research fono required that additional relational engagement be facilitated to bring participants together in the times we were able to meet. At each research fono in which participants could come together, there was extra time allocated for fa’afeiloa’i (welcoming and acknowledging the presence and reconnection for all). The face-to-face relational vā allowed teachers to develop mutual trust and openness to share Indigenous knowledges, including those of sacred cultural practices not for documentation (the tensions of sacred Indigenous knowledges are discussed later in this section). Throughout each fono, rich narratives of ancestral ties to Samoa were storied and retold, including experiences of Samoan childhood and the recognition of the holistic nature of the child that informs collective Samoan childrearing practices. The research process revealed the multifaceted and ongoing tensions of navigating Samoan Indigenous knowledge systems and their application to a New Zealand ECE context.

The diversity of teacher representation in terms of age and background within this phase of the project illuminated intersectional cultural nuances, such as differences between New Zealand-born Samoan and Samoan-born faiaoga and the distinction between the roles of “elders” and of younger Samoan teachers in the Aoga Amata context. The intergenerational reach of Samoan Indigenous knowledge was also reflected in the make-up of the Aoga Amata involved in the project, which included both established and newer centres. It became clear from the evolving talanoa at each research fono that faiaoga were grappling with the differences between Western and Samoan conceptualisations of quality pedagogy. Western notions, for example, required faiaoga to conform to licensing criteria and professional standards that are not always conducive to Samoan collective and holistic practices that affirm pepe meamea. In addition, faiaoga and leaders expressed pragmatic operational concerns, such as the shortage of Samoan/Pacific ECE teachers in the sector, particularly those who speak Samoan fluently.

Negotiating sacred and spiritual knowledge spaces

Throughout the first phase of the study, moments of talanoa referenced spiritual ties and sacred obligations. The influence of Christianity upon Samoan epistemology and fa’a Samoa (Samoan way of life) was negotiated and dialogued with orientations to Samoan Indigenous allegory and Christian proverbs. The influence of Christianity on the evolution of fa’a Samoa is well documented by Samoan scholars. His Highness Tui Ātua Tupua Tamasese Efi (2014), a Samoan cultural knowledge custodian, encourages ongoing critical appraisal of Samoan cultural traditions through a Samoan standpoint. He also encourages greater reflexivity in the critique of Samoan contemporary practices. For our faiaoga and researchers, the motions or movement of talanoa carried the discussion freely between multiple paradigms, such as Indigenous thinking and Christian beliefs. The flows of talanoa generated Indigenous knowledge sharing; however, sā or tapu (sacred) knowledges were not as readily shared as aspects of Christian belief. The sacred Indigenous knowledge and practices for pepe meamea were not to be documented, as the genealogy of that knowledge belonged to specific aiga or nu’u (villages).

Conceptualising pepe meamea: Samoan Indigenous concepts and practice

This section responds to research questions one and two, bringing together Samoan concepts of pepe meamea alongside Samoan practices and developing the pepe meamea pedagogical framework. We hold space for expression in poetry as another method of analysis (Matapo & Allen, 2020). The poem stories the conceptual threads of our talanoa.

Pepe meamea

We knew you before your birth

Your value in collective worth

In dreams of the living, you bind

The past, present and future divide

Like the fanua we walk and whispers of ancestors talk

You are imagined in form.

The weaving that adorns

Belonging; your birth-right Inheritance and foresight

Intergenerational reaching

You come into being

Gafā ai aiga: Pepe meamea as living genealogy

Ongoing talanoa between faiaoga generated further conceptualisations of pepe meamea, adding to the complexity and depth of Samoan Indigenous concepts. The natural environment and ancestral relations were woven into the talanoa and articulated as being critical for the ola lauleilei of pepe meamea. Ola laulelei is underpinned by relatedness and encourages a way of understanding and interconnecting with the world through social, cultural, spiritual, and ecological genealogies. Faiaoga from Seugagogo Aoga Amata reported the importance of pepe meamea experiencing the morning dew. As part of their routine, they would take pepe meamea outside in the morning and sing with them:

“Fa’asau ma pepese i fafo.”

(Experiencing the morning dew and singing [to pepe meamea], outside.)

Faiaoga from Seugagogo Aoga Amata

Faiaoga reflected on pepe meamea as sa’olotoga (freedom) and the significance of pepe meamea as a collective construct. Through sa’olotoga, pepe meamea carry the continuum of freedom for the whole collective. An extension of pepe meamea sa’olotoga is the view that pepe meamea e gafā ai aiga ([pepe meamea] are an extension of living genealogy of their family/collective). Pepe meamea sa’olotoga and gafā ai aiga position pepe meamea as a manifestation of living genealogy, a position that binds the ancestral ties of pepe meamea to their aiga, fanua (land), and nu’u.

Faiaoga from the following Aoga Amata shared the following conceptualisations of pepe meamea:

“O le pepe meamea o le ola fou ma faamanuiaga.”

(Pepe meamea is a new life blessing.)

Faiaoga from Fotumalama Aoga Amata

“Pepe meamea o le pepe fou, o le pelega o aiga ma matua.”

(Pepe meamea is a new baby, treasured by families and parents.)

Faiaoga from Fetu Taiala Aoga Amata

Relational interactions: Hands, skin, and touch

Throughout the first phase of the research, faiaoga shared many references to the physical dimensions of their teaching practice with pepe meamea. Paying attention to the child’s physical wellbeing resonates with the practice of agatausili (Samoan cultural values), which are deeply rooted in love, respect, and service. The physical dimensions of pepe meamea were theorised through Samoan Indigenous thinking, meaning that they were intuitively connected to the interactions between people and the environment. Thus, the influence of “hands” or touch pedagogy surfaced: the way in which hands communicate with pepe meamea and play a vital role in ensuring pepe meamea are cared for through aputiputi (nurturing), loving, and gentle interactions. Samoan wisdoms are expressed through the hands, such as the traditional healing practices of fofō (healing massage) or milimili (hands rubbing warmth).

As a newborn, the pepe meamea requires experiences of touch that match the softness of their skin. A faiaoga from Seugagogo Aoga Amata mentioned that “pepe meamea o le moemoe pei o se aputi” (pepe meamea is a young tender shoot). Faiaoga discussed the skin of pepe meamea as mu’amu’a (fresh/ supple), and they noted that the pedagogy of the hands is part of the first experiences of touch for the pepe meamea. Pepe meamea experiences of touch after birth include si’i (being carried or held), and the hands that carry pepe meamea speak of alofa (love). This expression of love and care in practice, faiaoga reported, continues through their si’i interactions. Faiaoga noted how important it was to ensure that aputiputi moments are unhurried and the timing and pace of care practices follow the rhythm of pepe meamea. Such care interactions with pepe meamea are supported through the Te Whāriki strand of belonging (MoE, 2017).

Traditional Samoan pepe meamea wellbeing practices

A broad range of traditional pepe meamea wellbeing practices was considered throughout all research fono. Two in particular were frequently discussed: mama (chewing food for the pepe meamea) and fofō (mentioned above). How both practices were considered and discussed demonstrated a blending of cultural and physical definitions imbued with Samoan values. These practices of care and healing come with the collective blessings from the ancestors to ensure the living are nurtured. Traditionally, mama (Tui Atua, 2009) is the intimate practice between the pepe meamea and their mother, grandmother, or close aiga that prepares food for consumption. Through mama, alofa and fa’amanuiaga (blessings) are passed on from the older generations to support the living of the young pepe meamea. While faiaoga opposed the application of mama in an Aoga Amata context due to regulations, Fetu Taiala Aoga Amata faiaoga acknowledged that mama is still a living practice for pepe meamea in their homes.

Unlike mama, which can be practised in any aiga, there are cultural nuances involved in accessing the healing practice of fofō. The knowledge and skills of the taulasea (healing masseuse) are sustained through intergenerational transmission. The novice taulasea is usually chosen by a senior taulasea and taught the sacred responsibilities of healing in a process that ensures the sacredness, accuracy of knowledge, and practice of fofō. Some faiaoga and researchers reported that they were taulasea and frequently practised fofō in their homes. In the context of pepe meamea pedagogy, aspects of fofō can be adapted but not for the healing of specific ailments, which requires the taulasea.

Fala pepe

This section will expand on what evolved from research fono four, the full immersion Samoan lalaga event. Faiaoga, alongside master weavers from Falelalaga Village, spent a day together, sharing stories of weaving and reminiscing about childhood experiences in Samoa and the ways in which weaving practices have changed over time. The Falelalaga Village lead weaver, Saoatulagitagaloa Penina Ifopo, shared her stories of fala pepe (the Samoan baby mat) and, with the support of matua (Samoan elders) and faiaoga, explored the traditional practices of fala pepe weaving.

Traditionally, the fala was woven by the mother or grandmother before or while the mother was pregnant. The act of weaving fala pepe before conception or during pregnancy connects the weaver and the pepe meamea through alofa and gafā (manifestation of living genealogy). The faiaoga reflections described the significance of the weaving experience to extending their conceptualisations of Samoan intergenerational weaving practices. Faiaoga learnt concepts to implement lalaga as a relational and pedagogical practice.

The lalaga event included pandanus leaves grown and prepared in Samoa. The preparation of laufala (the pandanus leaves) for weaving grounds connections to the ele’ele (soil/blood), where the plant is nurtured. The significance of these leaves to the weaving of fala pepe in the New Zealand context is that they provide a material link to Samoan ele’ele and fanua (Samoan earth and land). Pepe meamea born in New Zealand may not have the experience of connecting to fanua in their early years, so the fala pepe—especially one woven from laufala from Samoa—plays a critical role in sustaining their ola laulelei (cultural wellbeing) and ola (life). The mat itself holds its own pedagogy to teach pepe meamea through living encounters, such as resting, playing, crawling, and touching, and is used with fofō to heal.

Researchers both participated in the weaving and talanoa and documented it by arranging audio recording and taking field notes and photographs. This fono engaged in lalaga and talanoa, where faiaoga talked freely about sensitive concerns, particularly the implications of language and cultural loss within their families and communities. Through their presence and wisdom, Samoan matua (elders) affirmed the importance of grounding Indigenous Samoan knowledge systems in the teaching of pepe meamea. Our Samoan matua expressed their concerns for the growing population of younger Samoans and the need for Samoan ontologies to be elevated within the consciousness of transnational Samoan communities. They shared their concern not only for New Zealand-born Samoans but also for Samoan youth in Samoa today. One faiaoga shared her personal aspirations to learn alongside her mother to revive Samoan cultural traditions within their aiga context. Another teacher talked about how lalaga could be applied to her assessment practice and noted that the new terms she had been introduced to could be woven into her pedagogy of care routines. New Samoan upu (words) were introduced to faiaoga (see Table 2), and the possibilities of lalaga within Aoga Amata contexts were explored.

| Fenū—Laufala so’oso’o | The single strand that continues the strand that is running out. |

| Matuau’u—o le matua o faiva, o le ta’ita’i o le fale lalaga, matua i le soifua ma le agava’a |

The master weavers may be older or younger; however, they are more experienced in weaving. |

| Matuau’u i le lalaga | Leader in weaving and guiding cultural protocols regarding weaving, including language and behaviour. Matuau’u emphasises the importance of holding laufala (strands) very tight so the mat will keep its structure. |

Faiaoga suggested lalaga practices relevant to their teaching, which included weaving with children, sharing stories of weaving practice, and integrating fala pepe into care routines such as sleep patterns or to help soothe and calm pepe meamea. Fala pepe were identified as a material conduit to transition pepe meamea between the home and the centre. Faiaoga were keen to explore fala pepe with their Aoga Amata community and to share their learning with fanau.

Ma’a tatāo

Pictured in Figure 1, ma’a tatāo (rocks to secure) are the rocks often collected by tamaiti (Samoan children) from the river to serve as securing rocks used while weaving the fala pepe. The ma’a tatāo holds the fala in place; it secures the direction of the weaving and supports the weaver to manoeuvre the threads. The rock, an everyday resource used in multiple ways, is foundational to the integrity of workmanship of the mat. The flexibility with which the rocks can be moved and shifted while retaining their purpose—“to secure”— corresponds to the adaptability of and cultural security associated with the fala pepe within an ECE context. The pepe meamea pedagogical framework sets out to ensure that future carriers of the culture and traditions withstand the winds of change. The framework must be mobile, like the fala pepe, to be utilised across different sites. The role of the ma’a tatāo is to hold down and secure the fala pepe as part of the weaving process; figuratively, they also hold the pepe meamea pedagogical framework in place.

FIGURE 1 Ma’a tatāo (rocks to secure) (images taken by Jacoba Matapo)

Samoan matua (elders) and the intergenerational practices of pepe meamea

Once its concepts had been co-designed and documented, the pepe meamea pedagogical framework and its five ma’a tatāo were further discussed in consultation with Samoan cultural elders. Through talanoa, matua corroborated the concepts underpinning the framework and the accuracy of Samoan pepe meamea practices through their own experiences and understanding. Eight women matua of ages ranging from 63 to 88 years supported this process. Most of these elders were born in Samoa, except for two who were born in

Aotearoa New Zealand and Niue. Talanoa brought out their experiences of pepe meamea in Samoa and New Zealand. The Samoan-born elders shared rich narratives of their gafa (genealogy) and fa’asinomaga (cultural heritage), their schooling in Samoa, and their migration to Aotearoa New Zealand; they described coming to this country and experiencing a different sense of freedom. The matua discussed how important it has been to them to maintain the Samoan language and culture as parents and through their continued familial roles as grandmothers and great-grandmothers.

One matua opened up by saying:

“E ave uma o mataou alofa iā mataou pepe fa’apelepeleina.”

(We give all our love to our treasured babies.)

This matua’s talanoa had started with a discussion of the role of fathers and grandfathers in assuring the wellbeing of the whole family. The position of fathers/grandfathers in the research fono talanoa had not specifically mentioned the role of fathers and grandfathers, so the perspectives of these matua provided new critical insights into Samoan perceptions of pepe meamea and familial roles. One shared how her grandfather had delivered eight children without assistance from midwives.

One matua mentioned:

“Sao o tamā i tatou olaga.”

(Our collective wellbeing comes from our father.)

“Fa’afaileleina o tatou.”

(Working the land for us.)

Some matua discussed their traditional pepe meamea fofō (Samoan massage) and intergenerational healing practices passed through their mothers. One matua still practices fofō for her grandchildren and said that the power of touch is vital to pepe meamea wellbeing. Another matua grew up with her grandparents. She shared that her grandmother was good with herbs and would practise mama (chewing food), and she reported that her grandmother’s children never got sick. The matua healer who used herbs from the forest said her grandmother, who had not had access to Western doctors or medicine, taught her that Samoan herbs were important to healing pepe meamea. She reported that the blessings of health came from using Samoan medicinal herbs. Another matua spoke of the fala pepe as part of Samoan ola laulelei and life, as everything is done for pepe meamea on that mat, such as fofō (massage), bathing, and sleeping. The half-day talanoa with matua reaffirmed the dimensions of the pepe meamea pedagogical framework and provided clarity around the significance of its application in sustaining intergenerational cultural practices and wisdom for the ola laulelei of pepe meamea in Aotearoa New Zealand.

The pedagogical framework of pepe meamea

From the 89 Samoan pepe meamea concepts faiaoga expressed through ongoing talanoa and cultural encounters, five Samoan pedagogical concepts held a reoccurring presence. Through a process known as tofā’a’anolasi (critical analysis) of practice, discourse, and cultural understandings (Galuvao, 2018), researchers, faiaoga, as well as matua reviewed and corroborated these concepts and the practices associated with them. The researchers then used soalaupule (reciprocated talanoa for co-creation) with the faiaoga to search for the core common threads that hold all 89 concepts together. The five threads or themes were common to all 89 concepts, demonstrating the intersectional and complex layers of Samoan concepts and its nuanced meanings.

The five Samoan pepe meamea pedagogical concepts that emerged from these processes of tofā’a’anolasi and soalaupule are as follows:

Tofāmanino—Samoan Indigenous knowledge, philosophy, and wisdom

Faiva o le fa’atufugaga—Samoan pedagogies that include language and relational ethics

Fa’asinomaga—Identity grounded in genealogy and spirituality

Agatausili—Samoan values and customs

Paepaega—The ECE context, including relational worlds (human and non-human).

Pepe meamea pedagogical framework

Features of the five ma’atatāo concepts are presented in the following section, in Table 3. However, as a culturally holistic framework, the spaces between strands or threads are also considered part of the framework.

The five ma’a tatāo (securing rocks) or touchstones

| Tofāmanino Samoan Indigenous knowledge, philosophy, and wisdom |

The process of tofāmanino is a form of ancestral dialogue and is traditionally accessed through the sleep of the high chief to acquire ancestral wisdoms. It is fair to propose that children are capable of tofāmanino in their own ways of being and knowing the world and relationships. The pedagogy of tofāmanino recognises the strengths of pepe meamea in their being (and becoming) and the importance of pepe meamea accessing ancestral knowledge and wisdoms. For faiaoga, this pedagogy may be activated through intergenerational fanau storytelling, including (but not limited to) songs, dance, cultural materials, and wellbeing practices that share cultural knowledge. |

| Faiva o le fa’atufugaga Samoan pedagogies that include language and relational ethics |

Faiva is widely used in reference to mastery of skills and competencies. It is derived from Samoan cultural fishing knowledge, whereby faiva refers to the high-level mastery of navigators or fishers (Tagoilelagi-Leota, 2017). Many of Samoa’s proverbs stem from the expert craftsmanship of fishers and navigators. Faiva o le fa’atufugaga are pedagogical skills that equip or fa’atufuga (empower) teaching and learning. For faiaoga, faiva o le fa’atufugaga encourages teaching and learning through immersion in gagana Samoa to foster gagana competencies within the ECE context. In the early childhood context, practices include teaching cultural skills and encouraging appreciation and understanding of Samoan relational ethics. |

| Fa’asinomaga Identity, spirituality, and genealogy |

The concept of fa’asinomaga connects all Samoans to their cultural identity and heritage. Fa’asinomaga is a cultural birthright that ties identity to tofi (cultural rights), suli (heirs), gafa (genealogy), faalupega (village pedigree), and feagaiga (brother/sister protectorate relationships) (Tagoilelagi-Leota, 2018). The implementation of pepe meamea pedagogy (within a New Zealand context) considers the significance of sustaining pepe meamea fa’asinomaga within the ECE context. The spiritual life of pepe meamea is affirmed by honouring the collective aspirations of fanau/aiga (Toso & Matapo, 2018). In practice, this may involve telling antecedent stories of people and fanua (land), honouring sibling relationships, and integrating of fa’asinomaga experiences within children’s learning and assessment. |

| Agatausili Samoan values and customs |

Agatausili highlights the significant contribution of the Samoan cultural values of alofa (love), tautua (serving others), and faaaloalo (respect) to the wellbeing of pepe meamea. Aga refers to behaviour with tausili amplifying the hierarchical value of behaviour, which reminds teachers to show agatausili when engaging in the care of pepe meamea. Agatausili in the enactment of Samoan values and customs has a profound impact on the pepe meamea as a whole being. For faiaoga, all interactions are informed by agatausili, a value that encourages responsiveness and care, such as in the way they attend to the way pepe meamea communicate. Agatausili is expressed by the way pepe meamea are held, carried, soothed, and touched. In the ECE environment, agatausili fosters experiences of a Samoan way of life, as pepe meamea are given space to move and explore freely on fala pepe, experience the natural environment, and access cultural resources and materials. |

| Paepaega (Lotoifale) Understanding the lived realities and relational worlds of pepe meamea and fanau. Critical understanding of ECE context |

Paepae is the foundation on which a Samoan fale (open house) is built. Traditionally, the paepae is a foundation of smooth black rocks fetched from a nearby river to ensure the platform for the house is robust. In the context of pepe meamea pedagogy, paepaega places emphasis on faioga responsibility to deeply understand the contextual factors of the lived realities of pepe meamea and fanau, including the relational worlds (human and non-human) of pepe meamea. This understanding forms the foundation of faiaoga pedagogical interactions to strengthen relationships and decision making in the best interest of pepe meamea and their fanau. In addition, paepaega in the context of ECE includes critical knowledge of the political and social factors affecting the community and the centre context. |

The unfinished fala pepe (Samoan baby mat) pictured in Figure 2 that represents the pepe meamea pedagogical framework brings attention to the unknown spaces: the potential and emergent relationships that are held together through familiar, culturally grounded, Samoan onto-epistemological strands. The pepe meamea in their becoming are likened to the fala pepe. The pepe meamea pedagogical framework is depicted in the following image.

FIGURE 2 Pepe meamea pedagogical framework

Phase two

In the second year, six Auckland-based English-medium ECE centres were invited to join the research by engaging in cross-cultural mentoring partnerships with our Samoan teachers. Cross-cultural mentoring of faiaoga (as cultural experts) and early childhood teachers involved pairing Aoga Amata and ECE centres (listed in Table 4) to facilitate the sharing of knowledge, skills, and cultural perspectives. The selection of the six English-medium ECE centres was based on their proximity to the Samoan partner centre and the number of Samoan infant and toddler children the English-medium service had enrolled. The rationale for involving Aoga Amata and ECE centres in close proximity was to enable ongoing community partnership beyond the life of the study.

Three research fono were organised throughout the year to bring faiaoga and ECE teachers and researchers together to foster a community of learning approach to inquiry, exploring Samoan cultural concepts and practices of pepe meamea relevant to the ECE context. All three research fono focused on strengthening the cultural competencies and pedagogical awareness of teachers to enable them to implement aspects of the pepe meamea pedagogical framework.

| Aoga Amata ECE centres (36 participants in total) |

ECE centres (15 participants in total) |

|---|---|

| Seugagogo Aoga Amata | Otahuhu Happy Feet Childcare |

| Fotumalama Aoga Amata | Toddlers Turf |

| Taeaofou i Puaseisei Presschool (Raglan Street) | Immanuel Preschool Mangere East |

| Fetu Taiala Aoga Amata | Pukeko Preschool |

| Tumanu Ae Le Tu Logologo Aoga Amata | Inspire Early Learning Papakura |

| Taeaofou i Puaseisei Preschool (Winthrop Way) | Barnardos Early Learning Mangere |

Cross-cultural mentoring partnerships between Aoga Amata and ECE centres

The intention for the cross-cultural mentoring partnership was to promote the learning of Samoan cultural competencies, enhance culturally sustaining practices, and improve the quality of care for pepe meamea in ECE. Cross-cultural mentoring entailed the mentor and mentee working together to build a trusting and supportive relationship that would enable the mentee to acquire knowledge about culturally sustaining teaching practices (Crutcher, 2014). Cross-cultural mentoring has also been demonstrated to foster respect, empathy and understanding (DeWaard & Chavhan, 2020) among teachers of different cultural backgrounds, leading to more collaborative and effective teaching practices. In the first combined research fono, ECE teachers reported that they were interested in learning more about Pacific pedagogies, including accessing support for Pacific language integration and teaching strategies. Teachers were keen to develop an understanding of Samoan culture and learn ways to engage in culturally responsive practice with pepe meamea.

The group of mentors and mentees included experienced registered teachers, provisionally registered teachers, internationally qualified migrant teachers, student teachers, team leaders, full-time and part-time staff, and relievers. Teachers shared their cultural heritage experiences and the significance of culture to their personal pedagogies. Within the English-medium ECE centres, there were teachers who identified as New Zealand European, mixed-heritage, and migrant teachers. The migrant teachers identified cultural links to South Africa, Russia, Australia, and India and indicated that these links motivated their decision to engage in the project. Some teachers also identified as Pacific, with ancestral ties to Samoa and Tonga. From the English-medium ECE centres, one Samoan teacher was fluent in Samoan, and the other migrant teachers were fluent in their heritage languages.

Throughout the series of research fono, Samoan cultural values and beliefs were explored through ongoing talanoa between faiaoga and ECE teachers to support strategies to engage effectively with Samoan fanau and pepe meamea. Communication between ECE centre partners was bilingual, with gagana Samoa and English used to communicate and express ideas. One specific challenge that faiaoga reported was the collective responsibility of choosing which practices and cultural knowledge to impart, as some Samoan concepts and knowledge were sacred or tapu.

Fenū: The emergence of a Samoan concept for cross-cultural mentoring in ECE

The second combined research fono involved faiaoga and ECE teachers joining together to learn how to weave fala pepe and to talanoa about emerging shifts in their pepe meamea teaching practice. It was significant to see the partners meet each other (some for the first time, due to COVID) and observe cultural mentoring in action. The Aoga Amata faiaoga first went through the lalaga practices together to familiarise themselves with the cultural preparations and steps of weaving a fala pepe. After this process, the ECE teachers were welcomed to join alongside their respective Aoga Amata partners. Throughout the lalaga experience, expert weavers scaffolded and supported faiaoga and ECE teachers. Two faiaoga from the Seugagogo Aoga Amata, who were weavers, and other faiaoga who felt confident to weave, facilitated and supported the learning of their ECE centre partners. The weaving experiences, pictured in Figure 3, exposed teachers to Samoan Indigenous knowledge embedded within the whole process and the customs associated with fala pepe.

FIGURE 3 Images from research combined fono two: Lalaga with Samoan master weavers

Through ongoing collaboration and talanoa between faiaoga and ECE teachers, it became evident that a new concept of cross-cultural mentoring had emerged to nurture dynamic partnerships within the project. Partnerships were forged between members of the Advisory Group, between young and mature teachers, between teachers of different ethnic backgrounds, and between people playing different roles in ECE (e.g., supervisor, manager, cook, teacher aide, non-qualified assistant) and working across different localities. Through the lalaga research fono, a new upu (word)—fenū—emerged: the name of the loose laufala (pandanus strip) used to continue the weaving. The fenū is critical to the integrity and completion of the mat and is intentionally added at specific times to retain strength. The mentor–mentee relationship similarly requires careful consideration and adequate time for culturally sustaining practices to be taught and learnt. The fenū has to match the softness and size of the strand it is replacing, in the same way that the mentor should meet the mentee at their level of proficiency. The fenū strengthens the strand near its end, and the mat cannot be completed unless the fenū is used.

In the mentoring relationships of this research project, Aoga Amata teachers found it helpful to see themselves as the fenū for the teachers of English-medium settings. The concept of fenū in mentoring involves reciprocal obligations, so rather than seeing the mainstream teachers in a subordinate or novice position as in traditional notions of “mentor and mentee”, the Samoan teachers held expectations for their partner ECE teachers to fenū them back. In this conceptualisation, both mentor and mentee are viewed as strong and as having knowledge to contribute about infants and toddlers. Fenū holds the aspirations of the mat and a responsibility to sustain strength and balance for the next strand to come. A faiaoga from Tumanu Ae Le Tu Logologo Aoga Amata reported that, for her, “fenū is about the process”.

Following the combined lalaga research fono, several faiaoga reported that the key insights they gained included the importance of galulue fa’atasi (teamwork), being calm through the learning process, and working together. Another faiaoga reported that weaving together with her manager was an opportunity to “strip away the hierarchy”. ECE teachers reported that having patience and perseverance to weave was vital to them, including to deal with the soreness of their backs that came from sitting hunched over the materials. Faiaoga and ECE teachers expressed gratitude for having the resources, plenty of laufala (Samoan weaving materials), and the knowledge that was shared. The ECE teachers appreciated being mentored (fenū) by the Aoga Amata teachers (and supported by our weavers), so that they could understand the cultural significance of weaving and learn the weaving techniques for fala pepe.

Culturally sustaining practice and the pepe meamea pedagogical framework

In ECE, “culturally responsive” and “culturally sustaining” pedagogies aim to address cultural diversity but differ in their approach and aims. Tapasā (MoE, 2018) and Te Whāriki (MoE, 2017) recognise that culturally responsive pedagogies focus on building the cultural competency of teachers to acknowledge and incorporate learners’ cultural backgrounds and foster positive learning experiences and outcomes for culturally diverse learners and their families. Conversely, culturally sustaining pedagogies seek to sustain and enhance the cultural practices, identities, Indigenous knowledges, and languages of children from diverse backgrounds (Paris, 2012; Si’ilata, 2014). For Aoga Amata within a New Zealand context, culturally sustaining pedagogies have been a consistent focus for more than 35 years (Tagoilelagi, 2013). Samoan culturally sustaining pedagogy empowers and validates the cultural heritage of Samoan tamaiti and their fanau, aiga, and wider nu’u collective (Toso & Matapo, 2018). While culturally responsive pedagogies can be seen as a necessary first step to addressing cultural diversity, culturally sustaining pedagogies have the potential to create more transformative and lasting change by valuing and supporting the cultural identities, languages, Indigenous knowledges, and cultural rights of pepe meamea.

Teachers from Inspire ECE centre reported that the mentoring relationship with their Aoga Amata partnership centre had had a significant impact on their practice and described how, through fenū cross-cultural mentoring, they had learnt and adapted practices to be culturally sustaining of Samoan values, identity, and customs. At the final research fono, ECE teachers reported that they had since engaged fanau in their centres in fala pepe weaving and integrated Samoan mat time concepts. One reflected:

We were able to arrange a visit to our partner centre, where we got the opportunity to meet all the faiaoga and the fanau. We observed and were a part of their mat time. We were also delighted to be able to host them [Aoga Amata partners] in our centre, where they were also able to observe some of the care routines and rituals in our centre. So, one thing that we brought back for us when we visited our partner centre was when they took the mat time, they were sitting in a li’o, in a circle. We actually didn’t realise the significance of that, […] the faiaoga from the centre explained about the significance. She explained the reason they sit in a circle is to represent the fale, so the Samoan fale is in a circular shape […] So, yes, that is one of the things we have taken back to our centre and we are trying to incorporate with our infants and toddlers and even our over 2s room.

Another teacher from Inspire ECE centre noted:

We are delighted to be able to start our very own fala pepe and to be actually able to take it back with us and continue the weaving process at the centre.

The image in Figure 4 shows a Samoan mother and an ECE teacher weaving while the mother was visiting the centre. In the image, you will notice the non-Samoan teacher wearing an ie (lavalava) as a culturally appropriate practice when sitting and weaving. The teacher shared her experience:

So, that is the mum of one of our Samoan babies; she’s not one year yet, 8 months old. So, she was able to sit down […] and weave [and] do a few strands in our fala pepe, which we are hoping to be able to use for her pepe while she is still in our infant room.

FIGURE 4 Samoan mother and ECE teacher weaving

In response to the teacher’s reflection on practice, a faiagoa from Seugagogo Aoga Amata said:

I am very proud of what you did, informing and looking for a mother, a Samoan mother, to come in the centre and work together, because not only will you develop knowledge about how to weave and how to use it, but also your communication will be strong.

Ola laulelei (cultural wellbeing)

During this study, faiaoga and teachers created and developed the pepe meamea framework and reflected on ways to put it to practical use to transform their pedagogy, curriculum design, and philosophy to enhance the ola laulelei of pepe meamea. Two of the Aoga Amata centres, having completed a self-review of their infant and toddler room, renamed their classrooms pepe meamea. The renaming of their classrooms provoked ongoing conversations with their aiga and centre community to include key concepts of pepe meamea as part of their philosophy. The multiple fala pepe woven throughout the study have been used in different ways: within care routines, mat time, and spontaneous interactions. Pepe meamea have been able to access the fala pepe as a physical and spiritual cultural resource, connecting them to their fanua (ancestral land). Faiaoga and teachers have reported that pepe meamea are growing familiar with the fala pepe and, in some instances, are weaving them together with teachers throughout daily mat times. An outcome of this research is that the ola laulelei of pepe meamea is now better recognised by non-Samoan teachers as a product of a continuous journey and is understood as a shared responsibility of aiga, nu’u, and ECE centre communities. The study provided valuable initial insights into the pepe meamea pedagogical framework. To build on this foundation, extended research will further illuminate its long-term benefits, particularly its positive influence on the ola laulelei of pepe meamea.

Implications for practice

Currently in Aotearoa New Zealand, there are 4,596 ECE services, of which only 48 are Aoga Amata ECE, which is 1.04% of the total (Tagoilelagi-Leota, 2023). Despite fiscal challenges across the ECE sector and competing ECE philosophies and approaches to practice, Aoga Amata retains a strong commitment to sustaining Indigenous knowledges, cultural pedagogies, and practice for pepe meamea and tamaiti. However, with Aoga Amata ECE services underrepresented in the sector, most Samoan fanau do not have access to full immersion Aoga Amata to support the retention of their gagana, culture, identity, and spirituality. The intent of this study is not to undermine the value of Aoga Amata and their unique contributions to the ECE sector. Instead, this study seeks to highlight the value of fenū cross-cultural mentoring through which faiaoga and Samoan cultural experts can support ECE teachers to reconceptualise notions of infant and toddler practice from a Samoan reference point so they can be culturally sustaining and foster the ola laulelei of pepe meamea.

For ECE teachers of all backgrounds consulting with aiga and fanau regarding pepe meamea pedagogy, we encourage an openness to understanding Samoan early childhood ontologies, which are tied to ancestral practices and wisdom and may be dissimilar to normative ideologies or Eurocentric child-rearing practices. For non-Samoan ECE teachers, it is vital to understand the complexities of their Samoan community in terms of cultural access and aspirations. For example, not all fanau speak gagana Samoa or have access to aganu’u (village knowledge and protocol). Inversely, some fanau may be reticent to share Indigenous knowledge and practice freely due to the tapu nature of that knowledge or of specific practices (Matapo, 2021a).

Conclusion

The pepe meamea framework offers teachers ways of framing infant and toddler pedagogies that differ from what is predominantly taught in initial teacher education and through ongoing professional development. The five ma’a tatāo (touchstones) provide all early childhood teachers of pepe meamea secure points from which to develop culturally sustaining practices and engender co-agentic practices with pepe meamea and their fanau.

The exploration of culture and meaning in this research involved frequent and ongoing talanoa that revealed multifarious layers of understanding pepe meamea. The weaving practices experienced by all teachers in the study provided a wealth of metaphors for pedagogies within pepe meamea. The practice of cross-cultural mentoring between faiaoga and ECE teachers resonated with the metaphor of fenū. The fenū strengthens the woven strand that is about to finish; without it, the mat cannot be completed. In the mentoring relationships of this research project, faiaoga found it helpful to see themselves and the teachers from English-medium settings as fenū. Holding this perspective, both mentor and mentee are viewed as strong and as having knowledge of infants and toddlers to contribute. The lalaga metaphor also emphasises early childhood care and education as a collaborative endeavour through which Pacific and mainstream teachers are weaving the children of Aotearoa.

The culturally sustaining pepe meamea framework is intended to work alongside existing culturally responsive ECE frameworks, offering another set of ideas to be interwoven with Te Whāriki (MoE, 2017) and Tapasā (MoE, 2018), to ensure pepe meamea have a strong sense of ola laulelei through their educational experiences.

Research team and advisers

Dr Jacoba Matapo: Principal Investigator—Auckland University of Technology

Salā Pafitimai Dr Fa’asaulala Tagoilelagi-Leota: Co-Investigator—Principal Analyst at MPP

Dr Tafili Utumapu-McBride: Co-Investigator—Auckland University of Technology

Meiolandre Tima: Lead Samoan Research Assistant (Samoan transcriber and translator)

Francesca Febres-Muir: Research Assistant (ECE, psychology)—Massey University

Annastasia Matai: Samoan (Primary Teacher Education) Research Assistant—The University of Auckland

Merini Mauga: Samoan Research Assistant (ECE specialist, Samoan transcriber and translator)—Samoan Aoga Amata Society Aotearoa

Jules Skelling: Research Assistant (Disability and Inclusion Expert)—The University of Auckland.

Dr Chris Jenkin: Advisor AUT, Ethics specialist, ECE ITE

Dr Hinekura Smith: Adviser, UNITEC, Matauranga Māori and Indigenous research expert

Dr Karen Aspden: Adviser, Massey, ECE Infant and Toddler expert

Ene Tapusoa: Adviser, Aoga Amata ECE leader and cultural expert

Sadie Fiti: Adviser, Aoga Amata ECE leader and cultural expert

Meripa Toso: Adviser, ICL, ECE lecturer and expert in Samoan ECE and spirituality

References

Anae, M. (2016). Teu le va: Samoan relational ethics. Knowledge Cultures, 4(3), 117–130.

Anae, M., Coxon, E., Mara, D., Wendt-Samu, T., & Finau, C. (2001). Pasifika education research guidelines. Final report. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/pasifika/5915

Crutcher, B, N. (2014). Cross-cultural mentoring: A pathway to making excellence inclusive. Liberal Education, 100(2).

Dalli, C., Rockel, J., Duhn, I., Craw, J., & Doyle, K. (2011). What’s special about teaching and learning in the first years? Summary report. http://www.tlri.org.nz/tlri-research/research-completed/ece-sector/what%E2%80%99s-special-about-teaching-and-learningfirst-years

Davis, K., McKenzie, R. (2017). Children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture—O faugamanatu a fanau e sa’ili ai o latou fa’asinomaga, gagana ma aganu’u. Summary report. TLRI research project. http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/ projects/TLRI%20Summary_Davis%20for%20web.pdf

DeWaard, H., & Chavhan, R. (2020). Cross-cultural mentoring: A pathway to building professional relationships and professional learning beyond boundaries. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 14(1), 43–58.

Enari, D., & Matapo, J. (2020). The digital vā: Pasifika education during the Covid-19 pandemic. MAI Review Journal, 9(4), 7–11.http:// www.journal.mai.ac.nz/sites/default/files/MAI_Jrnl_2020_V9_4_Enari_02.pdf

Ete, F. (2013). A’oga Amata ma lona tuputupu mai i Aotearoa—The growth of A’oga Amata in Aotearoa. In F. Tagoilelagi-Leota & T. Utumapu-McBride (Eds.), O pelega o fanau: Treasuring children (pp. 35–50). AUT University.

Galuvao, A. S. (2018). In search of Samoan research approaches to education: Tofā’a’anolasi and the Foucauldian toolbox. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(8), 747–757.

Kolone-Collins, S. (2010). Fagogo: “Ua molimea manusina”: A qualitative study of the pedagogical significance of Fagogo-Samoan stories at night for the education of Samoan children. [Unpublished Master’s thesis, AUT University].https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/c33ca508-c20d-462b-bd3f-6ef95e9a7531/content

Koya-Vaka’uta, C. F. (2017). The digital vā: Negotiating socio-spatial relations in cyberspace, place and time. In U. L. Vaai & U. Nabobo-Baba (Eds.), The relational self.(pp 61–78). The University of South Pacific.

Leaupepe, M., Matapo, J., & Ravlich, E. (2017). Te whāriki a mat for “all” to stand: The weaving of Pasifika voices. Curriculum Matters, 13, 21–41. https://doi.org/10.18296/cm.0021

Mara, D. (2013). Teu le vā: A cultural knowledge paradigm for Pasifika early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. In J. Nuttall (Ed.), Weaving te whāriki (2nd ed.). NZCER Press.

Matapo, J. (2018). Traversing Pasifika education research in a post-truth era. Waikato Journal of Education, Te Hautaka Matauranga o Waikato, 23(1), 139–146.

Matapo, J. (2021a). Mobilising Pacific indigenous knowledges to reconceptualise a sustainable future: A Pasifika early childhood education perspective. Asia–Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 15(1), 45–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.17206/ apjrece.2021.15.1.45

Matapo, J. (2021b). Tagata o le Moana—The people of Moana: Traversing Pacific indigenous philosophy in Pasifika education research. [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Auckland University of Technology.

Matapo, J., & Allen, J. (2020). Traversing Pacific identities in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Blood, ink, lives. In E. Fitzpatrick & K. Fitzpatrick (Eds.), Poetry as method in education (pp. 207–220). Routledge.

Matapo, J., & Enari, D. (2021). Re-imagining the dialogic spaces of talanoa through Samoan onto-epistemology. Waikato Journal of Education. Special Issue: Talanoa Vā: Honouring Pacific Research and Online Engagement, 26, 79–88. https://doi.org/10.15663/ wje.v26i1.770

Matapo, J., & McFall-McCaffery, J. (2022). Towards a vā knowledge ecology: Mobilising Pacific philosophy to transform higher education for Pasifika in Aotearoa in New Zealand. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management—Special Edition Feature: Tertiary Education Policy and Management Advances in Pacific Islands, 44(2), 122–137.

Ministry for Pacific Peoples. (2020). Samoa population in New Zealand infographic. Author.

Ministry of Education. (2015). Participation in early childhood education. Education Counts. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/ indica.tors/main/student-engagement-participation/1923

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te whāriki: He whāriki matauranga mo ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Author.

Ministry of Education. (2018). Tapasā: Cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners. Author.

Ministry of Social Development. (2016). The profile of Pacific peoples in New Zealand. https://www.pasefikaproud.co.nz/assets/ Resources-for-download/PasefikaProudResource-Pacific-peoples-paper.pdf

Muaiava, S. (2022). Lauga—Understanding Samoan oratory. Te Papa Press.

Murris, K. (2020). Navigating the postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist terrain across disciplines: An introductory guide. Routledge.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97.

Rameka, L., & Glasgow, A. (2015). A Māori and Pacific lens on infant and toddler provision in early childhood education. MAI, (4)2, 134–150.

Rameka, L., Glasgow, A., Howarth, P., Rikihana, T., Wills, C., Mansell, T., Burgess, F., Fiti, S., Kauraka, B., & Iosefo, R. (2017). Te whātu kete mātauranga: Weaving Māori and Pasifika infant and toddler theory and practice in early childhood education. Summary report. TLRI research project. http://www.tlri.org.nz/tlri-research/research-completed/ece-sector/te-whatu-kete-mataurangaweaving-m%C4%81ori-and-pasifika

Si’ilata, R. (2014). Va ‘a tele: Pasifika learners riding the success wave on linguistically and culturally responsive pedagogies. [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. The University of Auckland.

Silulu, F, M, L. (2021). Samoan elders’ perceptions of wellness: A New Zealand case study. [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Auckland University of Technology.

St. Pierre, E. (2015). Practices for the “new” in the new empiricisms, the new materialisms, and post qualitative inquiry. In N. Denzin, & M. D. Giardina (Eds.), Qualitative inquiry and the politics of research (pp. 247–257). Left Coast Press.

Statistics New Zealand. (2013). Profile and summary reports. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-andsummary-reports.aspx

Tagoilelagi, S. F. (2013). Talafa’asolopito o A’oga Amata I Samoa, Pasefika ma Aotearoa. In F. Tagoilelagi-Leota & T. UtumapuMcBride (Eds.), O pelega o fanau: Treasuring children (pp. 19–34). AUT University.

Tagoilelagi-Leota, S. F. (2017). Soso’o le fau i le fau: Exploring what factors contribute to Samoan children’s cultural and language security from the Aoga Amata to Samoan primary bilingual classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand. [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Auckland University of Technology, Tuwhera. http://hdl.handle.net/10292/11022

Tagoilelagi-Leota, S. F. (2018). Suli, Tofi, Feagaiga, Gafa, and Faalupega: Nurturing and protectorate role of faasamoa for Samoan children. The First Years: New Zealand Journal of Infant and Toddler Education, Ngā tau tuatahi, 20(1).

Tagoilelagi-Leota, S. F. (2023, February 24). Malaga ma lau oso. Role of Pacific ECE research in amplifying Pasifika children’s mana and tapu [Keynote address]. Pacific ECE Symposium. Ministry of Education, Christchurch.

Tagoilelagi-Leota, S. F., Utumapu-McBride, T., & Matapo, J. (2022). Pepe meamea. World Studies in Education, 23(1), 97–114. https:// www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jnp/wse/2022/00000023/00000001/art00007

Toso, V. M., & Matapo, J. (2018). O le tātou itulagi i totonu o Aotearoa: Our lifeworlds within New Zealand. The First Years: New Zealand Journal of Infant and Toddler Education, Ngā Tau Tuatahi, 20(1), 3–5.

Tui Atua, T. T. T. E. (2005). Clutter in indigenous knowledge, research and history: A Samoan perspective. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 25, 61–69.

Tui Atua, T. T. T. E. (2009). The riddle in Samoan history: The relevance of language, names, honorifics, genealogy, ritual and chant to historical analysis. In T. Suaalii-Sauni, I. Tuagalu, T. N. Kirifi-Alai, & N. Fuamatu (Eds.), Su’esu’e manogi, in search of fragrance: Tui atua Tamasese Ta’isi and the Samoan indigenous reference (pp. 15–32). National University of Samoa.

Tui Atua, T. T. T. E. (2014). Whispers and vanities in Samoan indigenous religious culture. In T. M. Suaalii-Sauni, M. A. Wendt, V. Mo’a, N. Fuamatu, U. L. Vaai, R. Whaitiri, & S. L. Filipo (Eds.), Whispers and vanities, Samoan indigenous knowledge and religion (pp. 11–42). Huia Publishers.

Tui Atua, T. T. T. E. (2017). Forword. In U. L.Vaai & U. Nabobo-Baba (Eds.), The relational self: Decolonising personhood in the Pacific (pp. xi–xiii). The University of South Pacific Press and Pacific Theological College.

Utumapu-McBride, T. (2013). O tina o le poutu: Our mothers are the backbone of our families. In S. F. Tagoilelagi-Leota & T. Utumapu-McBride (Eds.), O pelega of fanau: Treasuring children (pp.185–194). Auckland University of Technology.

Vaioleti, T, M. (2006). Talanoa methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education, 12(1), 21–34.http://whanauoraresearch.co.nz/files/formidable/Vaioleti-Talanoa.pdf

Author notes

This project was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (UAHPEC22030).

Author biographies

Jacoba Matapo is the first Pro Vice-Chancellor Pacific at Auckland University of Technology. She is an Associate Professor, specialising in Pacific ECE and Pacific education research. She is of Samoan Dutch heritage, born and raised in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Her academic contributions centre on Indigenous Pacific communities and collective engagement, which informs her research, teaching, and leadership. In Pacific ECE, her research advocates for Pacific pedagogies for young Pacific children, traversing Pacific epistemologies and ways of being. Contact: jacoba.matapo@aut.ac.nz

Salā Pafitimai Dr Fa’asaulala Tagoilelagi-Leota has a PhD cultural transition from Auckland University of Technology (2017). The focus of her research explores factors that contribute to Samoan children’s cultural and language identity and wellbeing. Her research specialises in ECE transition, from the Aoga Amata context to Samoan primary bilingual classrooms in Aotearoa New Zealand. She has significant experience in organisational leadership and management at executive and governance levels within tertiary institutions.

Dr Tafili Utumapu-McBride is as an experienced academic in ECE initial teacher education and has expertise in mainstream and Pasifika ECE curriculum and pedagogy. She is fluent in gagana Samoa. Tafili has a PhD in Education from the University of Auckland (1998). Her doctoral research was one of the first in Pacific ECE, where she examined the impact of Samoan women’s roles in 21 Samoan language nests in Auckland. Her research focused on documenting how Samoan communities had evolved and how they maintained their cultural identity. She is currently a Senior Lecturer at Auckland University of Technology’s School of Education (BEd Core Programme Leader and Co-ordinator for the Pacific Specialty).

Meiolandre Tima is Samoan and was born and raised in South Auckland, New Zealand. She completed her MA degree in Youth Development at Auckland University of Technology in 2013, researching youth participation in Samoan churches.