1. Introduction

This project explored the affordances for young children in education settings of regular walking, reading, and storying the land with whānau, iwi, and community members for developing relationships with land and with people. Storying the land is described as communicating meanings, feelings, ways of being, including storytelling. We used a design-based research methodology in a community kindergarten, a state kindergarten, and a kōhanga reo that made regular haerenga (trips) to meaningful local places to analyse developing sensibility, knowledge, and relationships with land and with people as part of experiencing the meaning of democratic participation. We analysed pedagogical strategies that, within this process, promote integration across the curriculum and strengthen valued dispositions as “citizens of the world” and characteristics of being an educated person who is ready, willing, and able to be an active participant in Aotearoa New Zealand. In the kindergartens, we researched the development over time of children’s working theories across the curriculum and children’s efforts to learn and participate with others, as they walk, story, and read the land. In the kōhanga reo, our focus was on development over time of the child’s mana and identity as being Māori.

Walking, reading, and storying the land has been embedded in Indigenous ways of knowing for generations (Bang & Marin 2015; Durie, 2004; Penetito, 2009). In formal education settings, these processes have been used to generate children’s understandings about history, science, and the natural world (e.g., Bang & Marin, 2015) and to foster connections with literature, art, music, and dance (Barajas-Lopez & Bang, 2018). As an ecologist and scientist, Park (1996) came to know the landscapes of Aotearoa New Zealand’s coastal plains through reading the landscapes, which he likened to “collage, interweaving the patterns of ecology and the fragments of history with footprints of the personal journey” (p. 16). In a recent TLRI project (Mitchell et al., 2020), teachers from one early childhood education centre demonstrated how regular walks can cement a sense of belonging (Lees & Ng, 2020).

Wally Penetito (2009) writes broadly of “place-based education” as having an objective to develop in learners a love of their environment, of the place where they are living, of its social history, of the biodiversity that exists there, and of the way in which people have responded and continue to respond to the natural and social environments. This was our goal for young children in this study. Manning and colleagues (Manning, 2012; Manning et al., 2020) argue that the tenets of place-based education require teachers/ kaiako to collaborate with whānau, hapū, iwi, and community in curriculum design and delivery. Building on our earlier TLRI research projects (Cowie & Mitchell, 2021; Cowie et al., 2011; Mitchell et al., 2020), we explored the relational, conceptual, affective, and sensory aspects of regularly walking the same pathway.

The notion of “working theories”, which acknowledge ways that children make sense for themselves as they explore their world and become interested, curious, and creative in finding solutions to issues, provides a productive entry point for reconceptualising curriculum, learning, and teaching. Working theories are particularly suited to exploration within the conceptual frame of participatory democracy, since “Working theories encompass children’s embodied, communicative and social efforts to learn and participate effectively in their families, communities and cultures” (Hedges, 2021, p. 32).

Interdependent with learning dispositions, working theories are a key outcome of Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2017a), yet, until recently, they have tended to be neglected (Hedges, 2021; Mitchell et al., 2015). Hedges (2021), in her recent review of current understandings of working theories, identifies scope for future practice-based research investigations. Our research connects with several of these and, in particular, exploration and application of Māori concepts and examples.

2. Research questions

Our research questions ask:

- What does it mean for young children to act as critical democratic participants within their early childhood settings and kōhanga reo?

- How can educational practices based on walking, reading, and storying the land:

- Elicit and build on the funds of knowledge of children, families/whānau, iwi, and communities?

- Foster and integrate learning across the curriculum?

- Foster children’s capacity, inclination, and sensitivity for democratic participation?

3. Research design

The conceptual frame underpinning the study is participatory democracy. John Dewey expresses democracy as a form of living together, “a way of life controlled by a working faith in the possibilities of human nature … [and] faith in the capacity of human beings for intelligent judgment and action if proper conditions are furnished” (Dewey, 1976, p. 225). This requires opportunities for sharing, exchanging, and negotiating perspectives and opinions. Education settings might be places where values and practices of democracy are “born again” as Dewey expresses it, where children and adults construct a democratic culture. Can early childhood education centres be places where a democratic culture is lived, and what does that mean for young children developing as citizens? This framing contributed to the development of research questions and the way the project was set up as a partnership with teachers.

The research used a participatory design research (PDR) approach (Bang & Vossoughi, 2016) involving collaborative research processes with children, teachers, whānau, community members, and iwi through three separate case studies in a kōhanga reo, a community-based kindergarten, and a state kindergarten. Research followed iterative cycles, with each building on understandings gained from earlier research, discussions within the team, and readings.

Methods

Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa is located in Rotorua. It is licensed for 20 children, with up to eight children aged under 2 years. Currently, 100% are Māori children. Kaiako, tamariki, and whānau have built connections through the child’s pepeha and haerenga to marae, maunga, and awa. They researched the web of connections created with people, land, and the spiritual world. Rather than using the term “democracy”, their research was more aptly depicted as being about the power of haerenga and associated wānanga to recognise and reinforce mana.

Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten is a community-based kindergarten located in East Auckland. It is licensed for 40 children, aged 2–5 years. Many children are from immigrant families, especially from China and other Asian countries. Children are taken on weekly local walks around the Tamaki estuary. The kindergarten is working with Auckland Parks in “adopting” land around the Freemantle esplanade for planting and predator extinction. They researched relationships of children with the land and estuary, children with community, and children’s working theories portrayed especially through arts and stories.

Maunganui Kindergarten is an all-day kindergarten under the umbrella of Inspired Kindergartens in Tauranga. It is licensed for 30 children (maximum of eight under 2), aged 1–5 years, most of whom are Pākehā/European. Every fortnight, a group of the 10 oldest children, two teachers, and sometimes whānau, catch the local bus to Mauao and walk the track until they reach the puna called Waipatukakahu. They researched their walks, relationships built with tangata whenua, iwi, and community, and their developing curriculum.

Within each setting, three children and whānau participated as case study participants. They were chosen on the basis that they were likely to remain enrolled at the setting, were included in the regular walks/ haeranga; the families were, in the teachers’/kaiako opinions, likely to be positive about being asked and to benefit from being involved; and the children gave their assent. Teachers/kaiako in discussion with researchers made final decisions.

The three phases of the research involved initial meetings and wānanga in each setting; a period of data gathering and analysis; and collaborative data analysis, writing, and dissemination.

| PHASE 1: Wānanga (1 month) | |

|

|

| PHASE 2: Data gathering (14 months) | |

|

|

| PHASE 3: Data analysis (6 months) | |

|

|

| FIGURE 1. The three phases of the research | |

Transcriptions of wānanga, workshops, and discussions with teachers/kaiako also formed data for the project.

The collaborative process for writing for the NZCER journal, Early Childhood Folio is worth highlighting as a valuable method for others to consider. Participants had come to the wānanga prepared to work on writing an article from their own setting. This was a highly productive day, with researchers offering support and commentary on drafts for teachers/kaiako who were writing the articles. These processes strengthened final articles and generated deeper thinking about democracy and the affordances of walking, reading, and storying the land. Three articles were published in 2023 and a fourth article for the 2024 special issue has been accepted. Plans were also made for each team to present at the Early Years Research Centre conference on 8 July 2023 (two teams presented).

Data analysis

As well as the opportunities described above, the researchers worked in pairs and groups to identify, analyse, and report themes within the data that were linked to each research question, following stages suggested by Braun and Clarke (2012). A focus was on children’s developing working theories, mana, and integrated learning linked to the land through the walking projects. This was an iterative process in which we went back to the data and literature as we finetuned the selection of episodes and the analysis. For example, video recordings were watched and rewatched by two of the researchers who identified episodes that were related to literature, themes from other data such as whānau interviews, and research questions. These were discussed with teachers/ kaiako who offered their understandings. Some recordings were made by teachers/ kaiako who brought the recordings and their analysis for discussion with researchers. We built examples of democratic participation and integrated learning in context through analysis of storytelling, video recorded episodes, interview data, and documentation from the education settings. These included illustrations of the settings and of particular aspects that enabled children to act as critical democratic participants.

A second level of analysis was of the research process as a democratic partnership endeavour that potentially broadens conceptualisation of what counts as “knowledge” and valued learning, as whānau, community, and iwi contribute their funds of knowledge. We are exploring the research process from this framing.

Ethical and quality assurance processes

Research ethics approval was gained from the Division of Education Research Ethics Committee, University of Waikato. Particular attention was paid to cultural aspects and informed consent appropriate to each setting. Hoana McMillan took responsibility for interviews/discussion in te reo Māori with mokopuna and whānau in the kōhanga reo. Information sheets were translated into te reo Māori. At Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten and Maunganui Kindergarten, we worked in partnership with appropriate teaching staff. In Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten where there were many Chinese families, Olivia, a fluent Mandarin speaker, communicated with families where translation was needed. In all settings, particular care was taken to explain issues of confidentiality and anonymity for participants to enable them to make a thoroughly informed decision on whether to use their real names or pseudonyms.

Participating parents/whānau gave written consent for their individual interviews and wānanga discussions to be recorded and used as data.

Participating parents were asked to give written consent for video recording of their child, their own interview, and the gathering of learning stories, drawings, and talk of their child. They had an opportunity to view the video, see and amend a transcript of their interview, and view the specific learning stories, drawings, and transcripts of child talk so they knew what they were agreeing to. To obtain children’s assent, parents were asked at the start to discuss the project with their child, and if the child agreed to participate, the parent then asked them to make their mark on the consent form. The teachers/kaiako also discussed the project with the children, and they were again asked if they agreed that their photographs, learning stories, and drawings could be used for research purposes. They were able to decline without prejudice to their participation in curriculum activities, although none did so. If the body language of very young children indicated they were not willing to participate, this was respected as not assenting.

Teachers/kaiako gave written consent for video-recording of curriculum episodes and their group interview and discussions, and the use of learning stories.

The Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research (WMIER) undertook quality assurance for the project by ensuring that the organisation and processes within the project comply with all of the University of Waikato’s policies and procedures. Administrative and project management support for the project was provided by WMIER as and when requested.

4. Selected key findings

The findings explored here respond to the research questions in turn and discuss selected illustrative examples from analysis of data from the three settings to highlight points. These are presented under each research question as “key findings”. For each key finding, we discuss the strongest exemplar/s that best illustrates that theme. Apart from Key finding 1, which is specific to Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa, the themes were evident across all settings and the study as a whole. We then bring these together to discuss the overarching question “What does it mean for young children to act as critical democratic participants within their early childhood settings and kōhanga reo?” The final section of this report discusses implications for practice.

How can educational practices based on walking, reading, and storying the land elicit and build on the funds of knowledge of children, families/whānau, iwi, and communities?

Key finding 1:

Pepeha, haerenga, and wānanga strengthened connections for tamariki and whānau with people, with histories, and with ancestral whenua, hapū, and iwi.

Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa, working within the curriculum framework of Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo (Ministry of Education, 2017b) builds and sustains connections for tamariki with ancestral whenua/hapū/iwi, including through pepeha and kōhanga whānau visiting the marae, maunga, and awa of tamariki. Recognising and realising mana in relation to “te katoa o te mokopuna” (the whole child) and affirming Māori identity, are aspirations.

Kaupapa Māori theory guided interactions with researchers, kaiako, whānau, and mokopuna who took part in the project and the Māori cultural practice of wānanga (purposeful dialogue) was used to gather data. Within the kōhanga reo curriculum, Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo, the cultural settings of Mana Tangata (the power of people) and Mana Whenua (the power of the land) are particularly linked to the aim of the project.

Anne Salmond explains that:

people, land, waterways, and ancestors are literally bound together—thus the term tāngata whenua (land people), the people who belong in a particular place. The umbilical cord and placenta of their children and the bones of their ancestors are buried in the ground; and a single word may refer at once to a tribal boundary, an umbilical cord, a line of descent, or communication with ancestors. (Salmond, 2014, p. 294)

The Māori concept of whakapapa makes connections with ancestors, land and place, and with traditional creation stories. These connections are crucial in realising the goal of kōhanga reo for children to experience a curriculum that acknowledges who they are, where they come from, and their connectedness to the land.

The learning of pepeha and haerenga to the marae, whenua, and awa of each whānau is an established practice at the Kohanga Reo that supports this goal. The pou whenua (tribal landmark) that was the focus of the two haerenga for the research project was Mauao, the ancestral maunga of Hoana Tererewai Atwood who is a descendant of Ngai Te Rangi.

Before the haerenga, kaiako and tamariki listened to and told pūrakau of Mauao, painted pictures, made paper mache and learnt and sang waiata about Mauao and Tauranga Moana. These activities had developed after kaiako participated in the initial workshop for the project and were influenced by seeing the arts-based activities that were done before and after trips by Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten children. The value of these was described as “knowing what’s already there, and not just rocking up” (Hoana). Previously, there had been a tendency to treat haerenga more as “going on a walk rather than knowing the whakapapa or history of the area”. The preparation and follow-up deepened understandings and enabled purposeful exploration on the haerenga as tamariki made connections with what they had learnt. Some tamariki took photographs and returned to their artwork back in the Kōhanga to add from what they had experienced and seen.

A rōpū (group) of five pakeke (mokopuna aged 3–4 years) and some whānau went on the first haerenga to Mauao. The same rōpū and three mokopuna and their whānau from the rōpū nohinohi (aged 2–3 years) went on the second haerenga, following the same path. The rōpū pakeke were encouraged to share their knowledge of the land, the waiata, and pūrakau. In these ways, the rōpū pakeke took on leadership roles in passing on their knowledge and understanding to younger rōpū nohinohi and whānau. For kōhanga reo, the act is significant in terms of the intergenerational transmission of Māori knowledge.

FIGURE 2. Rōpū nohinohi exploring with kaiako during their haerenga

An iwi representative, Matua Des Heke, came too, pointing out landmarks and talking about significance, naming, histories, and customary practices as he walked with kaiako, tamariki, and whānau. He told stories that painted vivid pictures. He offered a depth of knowledge that connected that exact place with its past and brought a reading of the land that went far beyond what could be seen. He pinpointed artefacts, such as pipi shells and rākau, and linked these to how they were used in the past. His talking helped make sense of environmental degradation and reasons for the restoration that is happening currently on Mauao.

Most of the tamariki were off exploring rather than listening during his telling. On the other hand, it was immensely useful for kaiako to gain that information and bring it back to the Kōhanga. Prior to going on the haerenga, kaiako had been reading stories about Mauao and tamariki learnt a waiata about Mauao and the iwi in the area. When they had finished the haerenga they sang the waiata for the maunga and iwi representative.

These processes of preparation, haerenga, and wānanga within the kaupapa of Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa created and sustained strong connections amongst kaiako, tamariki, and whānau and the places in which they live and belong. Discussions in wānanga where whānau were asked about the significance of haerenga for themselves and their tamariki offer many examples of complex, layered, and deepening relationships. The last pātai was around understanding of relationships with the whenua, with people, and whether through haerenga there had been shifts. He aha o whakaaro mō te hononga ki te whenua, ki te whānau, ki ngā tāngata. Kua pēhea te ahu o ō whakaaro? Think about connections with the land, with the family, with the people. What are your thoughts? The quotations below illustrate whānau views.

Hononga ki te whenua: Connectedness to land. Tamariki strengthened their own connections to their iwi and whenua and came to understand the connections of all Kōhanga tamariki to their own whenua.

… we will go to Tauranga and they’ll see Mauao and they know that that’s where Waiorangi or Hoana are from, mmm, and I’m always blown away by that. (Hinewai)

Hononga tētahi ki tētahi: Connectedness to each other.

Even though we see each other as often as we can here with Kōhanga we don’t get to have those conversations until we’re on these haerenga, or you know find out a little bit more about each other. (Latoya)

Whakapapa ā kōhanga reo: Kōhanga reo connections. Whānau described the connection as “whakapapa ā kōhanga reo” which encompasses knowing the genealogical links of the whānau collective attending kōhanga reo.

Haerenga strengthen the Kōhanga unity, like we said before, so our connections with each other, our relationships, we’re not just chucking our kids through the door and that’s it; it’s learning for everyone in terms of our connections to the whenua, whakapapa. (Hinewai)

I like finding out where we’re situated, what iwi is here, what … maunga … I like to know where our Kōhanga is situated, it’s just all these deeper connections. (Latoya)

Iwi connections:

I mean it’s pushed me to go back home, and take the kids back home and so it’s put me out of my comfort zone like going back to our marae, Ngati Raukawa. That was hard but it was also amazing and I’m glad that we did do that and now I’ve opened that door we’re keen to continue to go back and my tamariki can go there and they know that’s where they’re from. (Tori)

Connections through loss: Some whānau did not learn te reo Māori as children, and others were raised away from their tribal areas. The Kōhanga experience offered opportunity for them to connect with their language and culture and offered the same opportunities for their children.

I think the cool thing is like we’re all, you know on the same page in terms of trying to find connections for our kids for whatever reason you know my parents didn’t know. So here I am trying to find things so that they [his children] have it from day one and they’re not going places trying to figure things out, it’s just there and it’s normal. (Tyler)

Spiritual connections:

I don’t know if she really shared too much on the haerenga but you get a feeling from their wairua that they’re just tau (settled) and they are connecting. It’s not a trip to rainbow’s end, aye, yeah, (laughter) they’re fully, spiritually aware of what they’re seeing. (Tyler)

Hoana encapsulated some themes in a summary at the end of the wānanga.

What we found is that Mana Tangata is more than our friends, whānau, and community sitting alongside each other. Whiria te taura here is about weaving together our friends, whānau and community so they are strong and in sync with each other. The threads can come together in many different ways. For our Kōhanga reo whānau, the whenua played a unique role in realising these connections and te pā tahi o te whānau—the oneness of whānau. (Hoana)

Wally Penetito (Penetito, 2009, p. 23) notes the “creative tension” between individualism and collectivism and that neither can be taken for granted: “Where one’s mana ake (unique individualism) is encouraged to develop, rangatiratanga (self-determination) for the collective identity is also facilitated.” They fully develop with each other in a “relational totality”. These interwoven processes of development were facilitated for tamariki through pepeha and haerenga.

Key finding 2:

New learning is created and passed on through inquiring teachers making meaningful connections with land and with people.

Maunganui Kindergarten’s regular fortnightly walking excursions to Mauao with the 10 oldest children began after teachers realised the importance of returning to the same place, so that children have opportunity to know the place well. It was through regular walking and being encouraged to find out about the land, its past, and present, that teachers deepened their understanding of what the land is about. They used their new understanding in the curriculum and pedagogical practice, and this seemed to have a ripple effect, with children passing on their stories and feelings about the land to their own whānau, and whānau including these in their home experiences.

In planning the research in Maunganui Kindergarten, teachers were encouraged to find out more about the local history and knowledge of Mauao from tangata whenua and local iwi. This followed the advice of Wally Penetito that “The Māori knowledge that gets into the learning institutions should be a selection from local whānau/hapu/iwi sources … local whānau/hapu/iwi must decide what should be available and how it should be made accessible” (Penetito, 2001, p. 24). Teachers said this was challenging for them, particularly because Mauao has ownership from four iwi. They were fortunate to form a relationship and speak with Dean Flavell, Chairperson of Mauao Trust Board (Mauao Trust—the entity entrusted to hold and govern Mauao on behalf of the Tauranga Moana iwi), who offered important messages.

Dean Flavell explained some things he wanted teachers to do with respect to Mauao and reasons why.

First, it was important to treat Mauao with respect for the significance of the maunga as a taonga. He asked the kindergarten community to “treat Mauao more like a grandfather”, he asked them not to treat Mauao like “an outdoor gym”, he asked them to personify Mauao. Head teacher Catherine explained that when they first went to Mauao the children “went a bit crazy” disturbing the environment as they looked for insects and investigated plants, trees, waterways, rocks, holes in the ground, and so on. These ideas changed the way adults and children interacted with Mauao towards a caring and respectful relationship based on greater understanding of ecology, history, and cultural significance.

Secondly, Dean Flavell asked adults and children to say karakia at the beginning and end of their excursions. The story of developing the karakia with participation of whānau, teachers, and children is described in response to Research question 3.

And I think one of the learnings from this is that if you ask tangata whenua then you do what they ask, you know, even if it may not be convenient to you … Asking those things, it was transformative. Absolutely transformative. (Catherine, head teacher)

Unplanned encounters with passers-by offered opportunity for further learning, such as meeting a couple at the puna Waitapu where the kindergarten group was saying karakia. The couple used water to whakanoa and cleanse themselves, a practice that they explained to the children and which the kindergarten adopted.

FIGURE 3. Children are becoming familiar with the concept of whakanoa

These are two of many illustrative examples from a group of inquiring teachers who learnt from their local maunga and from each other, whānau, community members, and iwi representatives. The land itself was a binding force that cemented their sense of purpose, interest, and love.

Cultural and historical understandings were passed to and from teachers, children, and whānau. Kindergarten parent Gemma, speaking in interview about what she liked about the kindergarten, encapsulated some of this when she likened “the kids’ exposure to te ao Māori and te reo Māori” as “a gateway for us to be involved as well”. She said the kindergarten trips and involvement with “the true history” “activated” understanding “in the kids’ minds” so they accepted what they learnt as “normal” to learn. She regarded opportunity to go on the trips herself and what she learnt about the history of the area and Mauao as beneficial for the whole family.

Ngaria, talking about her daughter Peata, in response to the question, “Does she have any special feelings about the places she visits or is it just outside?” spoke of a sense of ownership, belonging, and confidence, derived from familiarity.

Teachers commented on their own learning. “Had we not gone [on the trips] we would not have known so much” (Catherine, head teacher).

In summary, teachers questioned their own knowledge base and were open to new ideas and learning. They were willing to persevere and meet challenges in seeking to build relationships with others and learn from their relationships with iwi, community, and the land. Pamela Oberhuemer (2005) used the term “democratic professionalism” as a concept based on participatory relationships and alliances, and emphasising co-operation and collaborative action with others in the local community. Teachers at Maunganui Kindergarten illustrate this concept in action. Of particular importance were their efforts to move out of their comfort zone and use the knowledge they gained to make changes to their practice by incorporating Māori knowledge.

How can educational practices based on walking, reading, and storying the land foster and integrate learning across the curriculum?

Key finding 3:

Sustained access and deep observation of the land provide a platform for the development of curriculum knowledge.

Jacqui Lees, the head teacher of Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten, described the walking excursions as “knowing the land through your body, and through your feet, and if you walk it, you have a sense of connection to it and a relationship with it”. Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten is located close to the Tamaki Estuary. Children do not need any intervening transport to access their outdoor experiences, providing for an immersive local experience from start to finish. With various routes through the land and local neighbourhoods, the walks allow children to see the land from a variety of vantage points, not just from one or two (Ingold, 2011).

Sustained access and engagement support children to integrate cross-curriculum learning as they look deeply at the land across the seasons, learning the context and rhythms of the natural world (Postlewaight et al., 2023) and developing working theories about what they encounter.

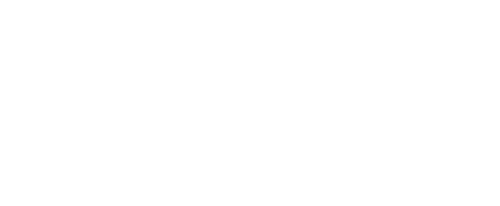

The extensive knowledge of the local area that children developed from these walks resulted in a mapping project that combined children’s experiences of walking with their learning in the kindergarten. Gowers (2022, p. 260) writes that “map-texts are viewed as a way of linking young children’s experiences to the contexts in which they occur”. Children began to map the land as they had experienced it on a long roll of butcher paper, adding to their map a little bit at a time after each walk. The map-making approach drew on art-based pedagogies that Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten have employed for some time. In this approach, the map-making process was used as a multi-modal meaningmaking process, where understanding emerged through the process of collectively producing the map (Walker, 2011).

FIGURE 4. Children’s collective map of the land around the kindergarten

This process of map creation unfolded the children’s geographical knowledge about the land. While the map is not drawn to scale, the relationship of geographical features to each other is accurate, as is the approximate shape of the harbour. The map includes features children had directly observed from their walks (for example, the layout of the kindergarten and the surrounding church park area) as well as some more creative elements such as the tiger shark and mermaid. Prominent features of the public landscape are depicted, such as the harbour, bridge, and main road, but these are interspersed with the personal: “Mum”, “Mum’s car”, and “Ajeet’s house” (kindergarten friend) are represented as thoughtfully as any other feature. The art of the map is secondary to the meaning of the map, where meaning is decided by the children as a representation of how the estuary area looks to them, and imbued with features they see as important.

In a second phase of the mapping project, the work took on an historical approach. A teacher supported the children to think about what the estuary used to look like. This work started with the children formulating working theories about the land of the past, which the teacher then extended on by using historical photos, information from the internet, and as crucial points for exploration (Ng et al., 2023). While physically walking around the land enabled the children to view the land from different vantage points, researching the history of land added a time-related vantage point that allowed them to see how the land, and the use of the land, had changed over time.

A bicultural vantage point was added with the introduction of two local pūrākau, Pakūranga Rāhihi (the battle of the sun’s rays) and the pūrākau of Moko-ika-hiku-waru, an eight-tailed taniwha who came with the Tainui waka. Both stories encouraged bicultural ways of engaging with the land and were again explored through arts-based pedagogies. In the case of Moko-ika-hiku-waru, children created a short film, using a model of the taniwha that the children had built. Using different modalities to engage in meaning making further supported children’s curriculum knowledge, in addition to providing meaningful cultural perspectives.

FIGURE 5. Te Pakūrangarāhihi live in the estuary (Ng et al., 2023)

The story of nature man and nature woman, a related but separate story, focuses on how opportunities and relationships encountered through engagement with the land support curriculum development.

During their walks along the Tamaki Estuary, the children and teachers had discovered what they called a “secret garden”. This was an area on the bank where someone had built garden boxes, created plantings, added a garden seat, retaining wall, and even built paths. Despite visiting the garden for many years on their walks, it was only in 2022 that the children had begun to wonder who had made the garden and cared for it. The working theory that emerged from these wonderings was that the nature man had made it. As the teachers continued to explore the theory of the nature man with the children, a nature girl (later renamed nature woman) also emerged.

In another example of arts-based pedagogy, children created models out of clay and other natural materials to represent their theories about what nature man and nature woman looked like.

FIGURE 6. Children’s models representing their theories of nature man

Back at the kindergarten, these working theories about nature man and nature woman evolved through stories, clay models, and more thinking as children shared their theories with teachers and each other. Hedges (2021) writes, “More than about thinking and knowledge development, working theories encompass children’s embodied, communicative and social efforts to learn and participate effectively in their families, communities and cultures” (p. 32). A few of the theories exemplify how the children used their theories to explain, explore, and expand on the idea of nature man and nature woman, connecting the fantastical through the common as they used what they knew to reason, connect, and extend ideas.

Children’s involvement with the land saw them become story sharers and story participants without becoming story owners as they developed collective knowledge about the land. Meeting the real nature man and nature woman, who had created the secret garden, gave context and dimension to imagined stories and evolving working theories—but at the same time, meeting the children added to the story of Ross and Carol. They spoke of their involvement, something that happened just before they moved away.

Ross: It’s enormous. It really is. My heart is so greatly warmed by their interest, their affection, their spontaneity, their engagement, their wanting to engage with the land, with the trees and the plants, with everything. So, for me, it’s very, very heart warming, I appreciate their interest, I encourage it.

Carol: To me, it’s just like magic. Because as you get older—we’re 70s and 80s—you sort of take things for granted, and you don’t look at things through those eyes of little children. And looking at things now through their eyes. It’s just like pure magic to us. And it was just, I think it’s just so wonderful what the kindy teachers are doing, taking the children around, making them aware of nature, and it gives us hope for the future, that there are these lovely teachers out there that are teaching our children.

In summary, at Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten, children are positioned as experts in their own lives, and as competent communicators of their own experiences, with the ability to express their views and experiences in many different ways (Clark, 2017). This positioning was supported by adults who consciously used multimodal forms of expression through arts-based pedagogies to tease out children’s thinking, ideas, and understandings of the world around them. Creative outlets encouraged engagement. These approaches illustrate Clark’s (2017) point that “the question is not whether children have any knowledge to convey but how hard we work to make sure every child has the opportunity to share their point of view” (p. 21). The points of view—the theories of children were rich and interesting because of the process they were involved in. Creative, physical engagement encouraged deep thinking.

How can educational practices based on walking, reading, and storying the land foster children’s capacity, inclination, and sensitivity for democratic participation?

In response to Research question 3, we give a short example from each setting.

Key finding 4:

A relationship with the land supports a sense of responsibility and reciprocity.

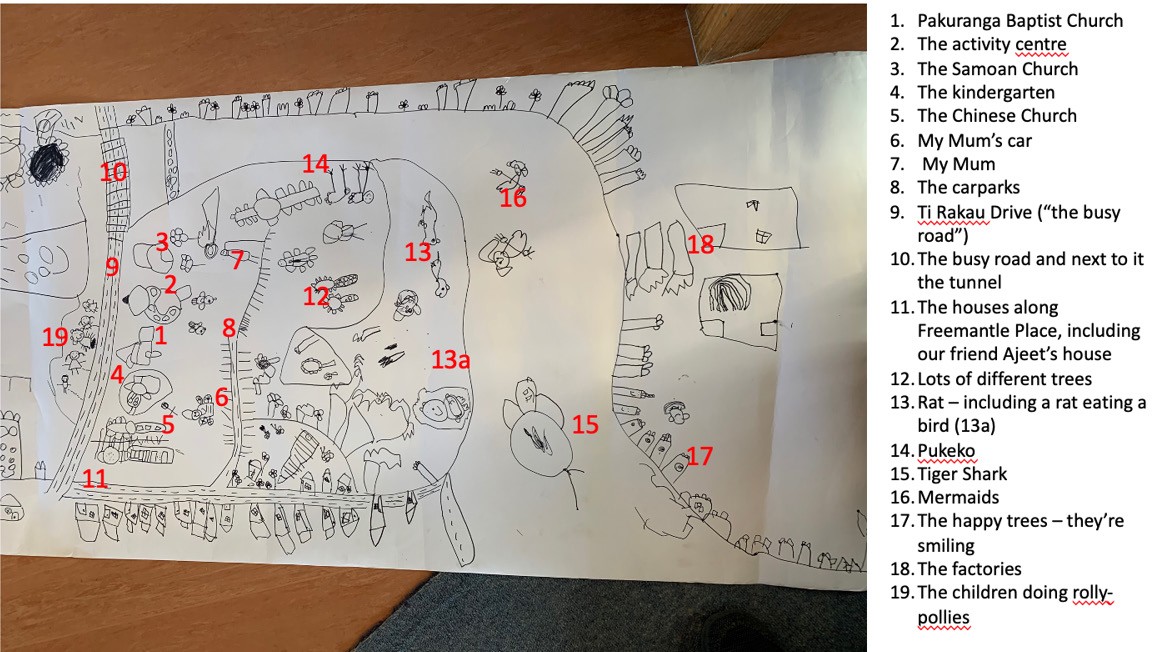

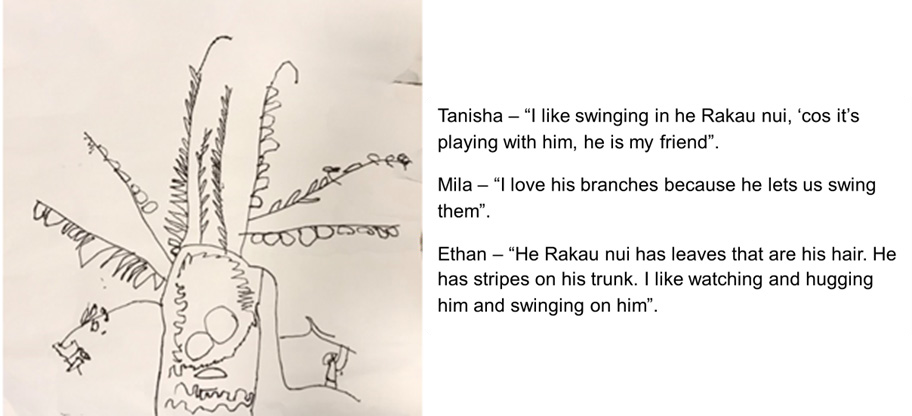

The Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten children had developed an affection for a big tree by the bridge that they saw regularly on their walks. Over the years, children had given the name “he Rakau Nui” to the tree, one that each new generation of kindergarten children kept. When the road nearby was scheduled to be widened for a new bus lane, he Rakau Nui was in its path, and subsequently scheduled for removal. The children were unhappy about this. However, at an Enviroschools meeting, one of the teachers found herself next to a representative from Auckland Transport. When this representative heard about the situation with the tree, she suggested gathering the children’s ideas and stories about he Rakau Nui in order to build a case for having him moved rather than cut down. Shortly afterwards the teachers took the children to visit he Rakau Nui and asked them to tell the teachers what they loved about the tree, including what was important about him. These perspectives were again recorded using an arts pedagogy approach. These pictures and perspectives about he Rakau nui then became part of the information prepared for Auckland Transport.

FIGURE 7. Children’s drawing and stories of he Rakau Nui

In their perspectives, the children talk about the tree as though he is a friend. They talk about their shared experiences with him that have built a relationship with the tree over time. Children are motivated to take up the role of citizens as they engage with local government processes to advocate for he Rakau nui.

Key finding 5:

Haerenga and waiata empower tamariki and foster relationships with Mana Whenua, Mana Atua, Mana Tangata, Mana Reo, and Mana Aotūroa.

The concept of “mana” is an overriding principle of Te Whāriki a te Kōhanga Reo (Ministry of Education, 2017). Reedy (2019) writes that the child “having mana is the enabling and empowering tool to controlling their own destiny” (p. 37). Within kōhanga reo, the mana of each child is fostered through five cultural settings: Mana Atua (The power of the Gods); Mana Whenua (The power and status of the Land); Mana Tangata (The power and status of People); Mana Reo (The power and status of the Language); and Mana Aotūroa (The power and status of the Environment) (Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust, 2020). As children experience these cultural settings they are observed in relation to four dimensions of development namely: Tinana (physicality); Wairua (spirituality); Hinengaro (cognition); and Whatumanawa (emotion). Recognition of mana for Māori children promotes their agency, a concept embedded in democratic citizenship.

In the examples below, Hoana who had been in the rōpū pakeke on the two haerenga and for whom Mauao is the ancestral maunga, displayed her enduring relationship with the maunga that deepened over the following months. The waiata learnt and the actual walking the land played a pivotal role for Hoana to realise her mana.

The first example links to the cultural setting, Mana Reo. After the haerenga, Hoana’s whānau observed the way she was fixated on singing all the waiata the mokopuna had been learning about Tauranga Moana and Mauao while riding her bike in the forest and around the home. One day while travelling home with her mother she started singing “Tauranga Moana”. Hoana’s face lit up as she sang her song (whatumanawa), and recalled the name of her maunga, Mauao; and the tribes in the Tauranga region, (hinengaro). Her passionate rendition indicated the importance of these places and people to Hoana as a descendant of Tauranga Moana (wairua).

The second example is about Hoana after she had climbed Otanewainuku with her whānau in early 2023, a year after their haerenga to Mauao as observed by her parents. During the climb, Hoana took the time to connect with the Otanewainuku through touching the trees, the rocks, and the small leaves. Although it was an arduous climb, she didn’t complain once (tinana). Arriving at the top of the mountain the family spoke about Mauao, Pūwhenua, and her love for Ōtānewainuku, and the Hautere forest. Hoana was interested in looking for Mauao but couldn’t see him, but she knew the Patupaiarehe had dragged him to the sea (hinengaro). She sang the chant about the patupaiarehe “E Hika tū ake” that they had been learning at kōhanga reo and the same song that mokopuna sang at the base of Mauao when they had been on the haerenga. She sang with the same gusto as she had done previously, showing her happiness and love for her whenua (wairua).

FIGURE 8. Te piki i a Ōtanewainuku

In discussing the two haerenga to Mauao carried out during the research project, kaiako identified aspects that strengthened her learning. These were the need to come back more than once to the same place; the value of researching; and the significance of waiata as a way for tamariki to retain knowledge and keep sharing with their parents at home.

Our two short examples illustrate outcomes in action for Hoana, where mana was an all-encompassing value.

Key finding 6:

Listening to children as active contributors in co-producing curriculum enhances their agency, sense of ownership, and understanding.

A challenge for Maunganui Kindergarten was to construct a karakia in response to the Mauao Trust Board chairperson’s call to personify Mauao and to say karakia at the spring at the base of the maunga before embarking on the walks around the mountain. Initially, teachers asked a Māori parent to write a karakia for the kindergarten, but instead the parent asked them to go back and think about what the maunga meant to them and what they would like to say to the maunga. In this example, teachers supported the children to contribute their thoughts and views about Mauao. Listening to young children is not limited to the spoken word. However, the children and teachers had an established daily practice of sitting together, with each child having a turn at expressing their thoughts on matters of interest and importance. They used this forum to gather views.

The karakia related to Mauao, the maunga that was visible through the kindergarten fence and familiar through the regular walks. The conversations with the Mauao Trust

Board chair changed the teachers’ knowledge towards a greater appreciation of Māori understandings of maunga as taonga and influenced the teachers’ practice. Also important was the encouragement within the research project for children to be positioned as participants.

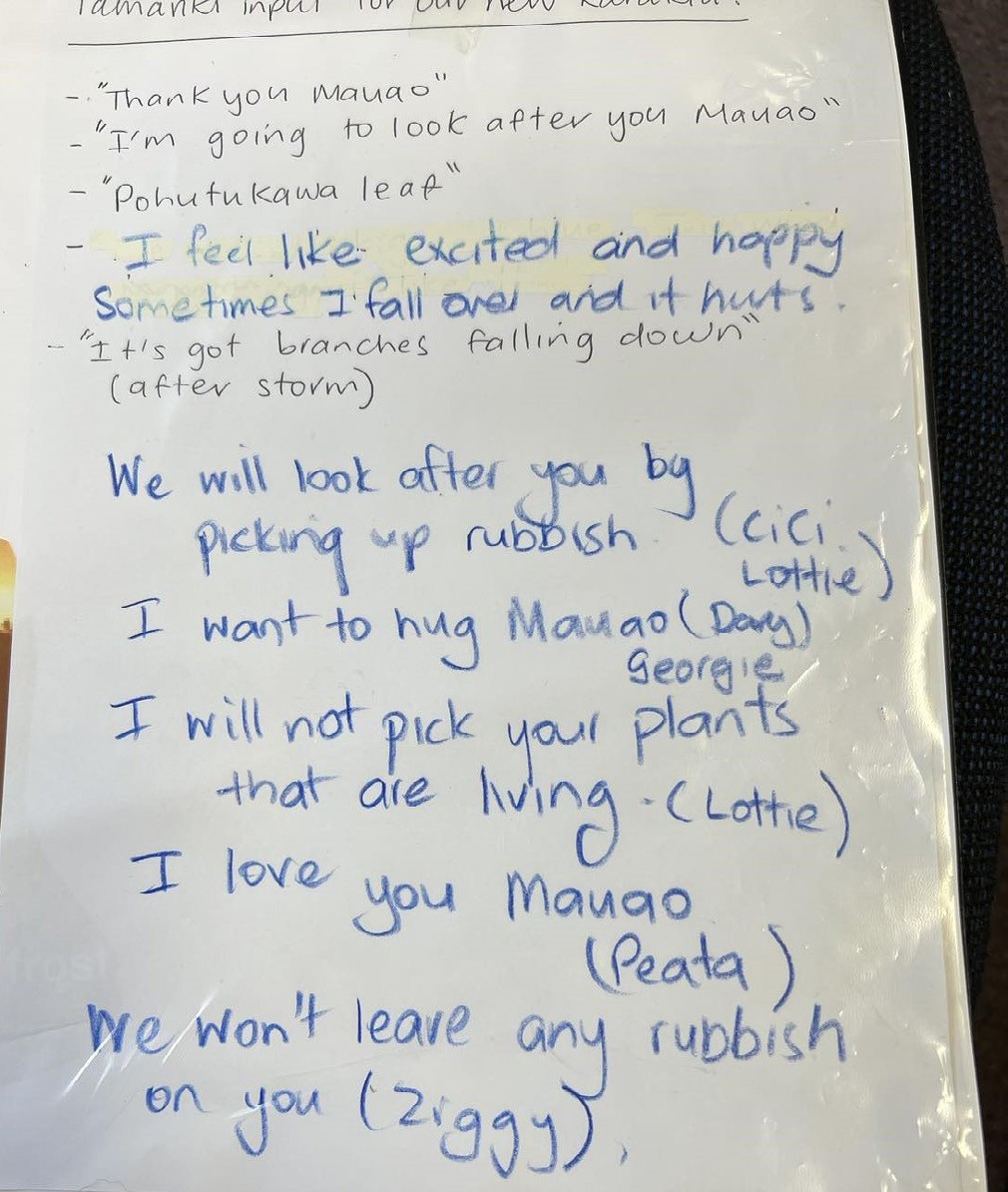

Teachers worked through a democratic process where children were invited to express their thoughts in response to questions like “What would you like to say to Mauao?” At first the children’s input was minimal but as time went on, they had more of an idea about what to say to Mauao. Some of the children’s ideas for the karakia, written down and compiled, are captured in Figure 9 and convey caring practices, gratitude, and feelings of interest, excitement and love. In a presentation about the project, teachers described the power of personification for children’s interest and learning: “Children really encapsulate this idea of personification. Their minds may be more open than adults. And this is how we normalise atua.”

FIGURE 9. Tamariki input for Maunganui Kindergarten’s new karakia

After children had talked, teachers expressed what they would like incorporated into the karakia—to acknowledge tangata whenua, express gratitude, and uphold the aspirations of tangata whenua.

The parent then embodied these ideas in writing the Maunganui Kindergarten karakia, a karakia which is learnt, owned by, and familiar to adults and children alike.

Maunganui Kindergarten karakia

Ko Ranginui e tū iho nei

Ko Papatūānuku e takato ake nei

Toitū te marae a Tāne Mahuta

Toitū te marae a Tangaroa

E Mauao e

Anei mātou o hoa e tuku nei i te aroha nui Haumi e, hui e, taiki e

We acknowledge Ranginui above us

We acknowledge Papatūānuku below us

Let the realm of Tāne Mahuta be sustained

Let the realm of Tangaroa be sustained

Oh Mauo

Here we stand, your friends, sending you our gratitude and love

Let us join, gather, unite.

Catherine described how the teachers explained karakia to the children:

So we’re entering this place now. And it makes us think about who was here before us. And it’s a time just to slow down and keep ourselves safe. Say goodbye. I also like to, as part of it, get the children to say more about where we’ve been … I like them to say what they enjoyed and what was the best part of their day. And what are they happy about? … So it’s just instilling that value of gratitude and respect. Then I think that’s what Dean was after for us. To enhance that sense of kaitiakitanga. Looking after by not being too rough.

Through these processes of developing the karakia over time with opportunities for all to contribute and explaining and consolidating karakia as a usual practice, children became more thoughtful, caring, and confident in their relationship with Mauao.

5. What does it mean for young children to act as critical democratic participants within their early childhood settings and kōhanga reo?

In this final section, we synthesise our findings to consider the overall research question. First, we discuss the conditions that supported children to act as critical democratic participants. We then turn to what this might look like in relation to context.

The early childhood settings and kōhanga reo in our study offered facilitating conditions for children to develop as critical democratic participants. Jerome Bruner envisaged a democratic community as “a place where all participants are able to belong and make a contribution that makes a difference for learning, wellbeing and belonging; where they collectively create a world” (Bruner, 1998). Stephen Kemmis has argued that “a democratic education pursues both the good for each person and the good for humankind—and, one might add, the good for the community of life on Earth … the double purpose of education [is] helping people to live well in a world worth living in” (Kemmis, 2023, p. 13). In these ways, the question of democracy in education may be understood as encompassing possibilities for transformative change for people and the world. Peter Moss (2021) sums up democracy as “a way of relating to oneself and others, an ethical, political and educational relationship that can and should pervade all aspects of everyday life”.

Democratic structures in governance and decision making are features of each. The teachers/kaiako in our study expressed their philosophy in different ways. In each setting, the philosophy expressed commitment to mana and empowerment and a view of their kindergarten or kōhanga reo as offering transformative possibilities for children, their whānau, and the common good.

Within context, what does children acting as democratic participants within their kindergartens and kōhanga reo look like and mean? In the next section, we focus on democratic citizenship and mana empowerment as broad overall outcomes and consider some key attributes and the contexts in which they are fostered. These have arisen from our research and are not intended to be comprehensive.

Children are proud of who they are and knowledgeable about their identity. They acknowledge and respect the identity of other children. This is fostered in a context where connections are made with cultural identity, home funds of knowledge, and interests from home. Sustained connections with local lands offer an anchor for belonging in this place and a link to homelands. In kōhanga reo, whakapapa connections within the cultural setting of mana whenua are strengthened through te reo, waiata, pūrakau, and haerenga to ancestral lands. The participation of the kōhanga whānau contributes to collective strength and understanding.

Children look out for and take care of each other. This is fostered in a context where there is a culture of collaboration and connection, where all children are included and there are opportunities for children to empathise with and support others and to be supported.

Children take on leadership roles with respect to others and the land. They share their knowledge and skills and are open to listening and learning from others. This is fostered in a context where intergenerational knowledge is valued and promoted and sustained relationships are formed with the land.

Children acknowledge and give back to others. This is fostered in a context where there is a culture of reciprocity and teachers/kaiako promote expectations. Curriculum actions are planned to embed this reciprocity.

Children have agency. They make their views known and listen to others. This is fostered in a context where children are invited to contribute and are listened to. Children have time and support to express and develop their “working theories”. Teachers/kaiako use multimodal methods to enable children to express their thoughts.

Children engage with big issues of our time and advocate for a world that is more equitable and environmentally sustainable. This is fostered in a context that invites children to develop a love of others and place. Teachers/kaiako have a strong political– democratic understanding and support children to think critically about issues that are harmful to people and place. They may support children to engage in interactions with local or national government to advocate for positive solutions.

6. Major practice implications

In this final section, we highlight major implications for practice derived from our findings. These are written as messages for kaiako/teachers and other practitioners to take away and think about in their own settings.

- Walking, reading, and storying the land with children, whānau, iwi, and community members supports children to make enduring relationships with land and with people and come to belong. Our research found the importance of walking the same pathway, carrying out the same practices, and revisiting the same things regularly over time. The walking, reading, and storying as a cluster is significant: participants had to go and make connections with the land in terms of its past and present, to make their own story about what the land is about—all three came together to elicit and build on. The layering of experiences undertaken in an unhurried way offered opportunity for deeper connections and understanding. In the Kōhanga Reo, returning to the whenua was deemed necessary to feel its mauri (lifeforce). When children and other people become involved in this way, it becomes more than an enjoyable sightseeing visit. The experiences of Maunganui Kindergarten and Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa illustrate that it is possible to make regular haerenga/excursions even when the land is some distance from the setting.

- Connecting with funds of knowledge of whānau, iwi, and community members creates productive relationships and broadens the knowledge base for all participants as normative boundaries of what is “knowledge” were breached. Valuable new learning about the land was created through relationships made with iwi who decided what knowledge to make available. Teachers in the kindergartens who did not have existing relationships with iwi were motivated to find out who to approach and to sometimes step outside their comfort zone in making the connections.

- Processes of preparation and follow-up are as important as the haerenga/excursions for helping children/tamariki retain and expand knowledge and understanding. In our study, processes included children learning stories, pūrakau, waiata, karakia associated with the land, children depicting the land through artsbased methods, children’s working theories being encouraged and fostered in an unhurried way.

- Teachers/kaiako were researchers themselves, researching their own practice individually and with others. The opening up of discussion of experiences of haerenga/excursions and documentation within whānau wānanga, focus groups, and research teams contributed to growing understanding of how participants might support positive impacts for the individual and the collective. These processes supported intentional teaching.

References

Bang, M., & Marin, A. (2015). Nature–culture constructs in science learning: Human/non-human agency and intentionality. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(4), 530–544. https://doi. org/10.1002/tea.21204

Bang, M., & Vossoughi, S. (2016). Participatory design research and educational justice: Studying learning and relations within social change making. Cognition and Instruction, 34(3), 173–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2016.1181879

Barajas-Lopez, F., & Bang, M. (2018). Indigenous making and sharing: Claywork in an indigenous

STEAM program. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2018.1 437847

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 55–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Bruner, J. (1998, January). Each place has its own spirit and its own aspirations. Rechild, 3(6).

Clark, A. (2017). Listening to children: A guide to understanding and using the mosaic approach. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Cowie, B., & Mitchell, L. (2021). A sensory landscape of place as an invitation to belonging for refugee and migrant children in early childhood settings in Aotearoa New Zealand. Early Childhood Folio, 25(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0089

Cowie, B., Otrel-Cass, K., Glynn, T., & Kara, H. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogy and assessment in primary science classrooms: Whakamana tamariki. http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/ projects/9268_cowie-summaryreport.pdf

Dewey, J. (1976). Creative democracy: The task before us. In J. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey: The later works, 1925–1953 (vol. 14., pp. 224–230). Southern Illinois University Press [Original work published 1939].

Durie, M. (2004). Capturing value from science: Exploring the interface between science and indigenous knowledge [Paper presentation]. 5th APEC Research and Development Leaders Forum. Christchurch, New Zealand. https://www.massey.ac.nz/documents/486/M_Durie_Exploring_the_ interface_Between_Science_and_Indigenous_knowledge.pdf

Gowers, S. J. (2022). Making everyday meanings visible: Investigating the use of multimodal map texts to articulate young children’s perspectives. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 20(2), 259– 273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X211062750

Hedges, H. (2021). Working theories: Current understandings and future directions. Early Childhood Folio, 25(1), 32–37.

https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0093

Ingold, T. (2011). Being alive essays on movement, knowledge and description. Routledge.

Kemmis, S. (2023). Education for living well in a world worth living in. In K. E. Reimer, M. Kaukko, S. Windsor, K. Mahon, & S. Kemmis (Eds.), Living well in a world worth living in for all. Volume 1: Current practices of social justice, sustainability and wellbeing (pp. 13–25). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-7985-9_2

Lees, J., & Ng, O. (2020). Whenuatanga—Our places in the world. Early Childhood Folio, 24(1), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0075

Manning, R. (2012). Place based education: Helping educators give meaningful effect to the tangata whenuatanga competency of Tātaiako and the principles of Te whāriki. In A. C. Gunn, N. Surtees, D. Gordon-Burns, & K. Purdue (Eds.), Te aotūroa tātaki: Inclusive early childhood education (1st ed., pp. 57–73). NZCER Press.

Manning, R., Hetet-Owen, L., Puketapu, T., Puketapu, H., & Manning, J. (2020). Tangata whenuatanga: Reflections on how place-based education may assist kaiako to enhance Tiriti/Treaty relationships in local communities. In A. C. Gunn, N. Surtees, D. Gordon-Burns, & K. Purdue (Eds.), Te aotūroa tātaki: Inclusive early childhood education (2nd ed., pp.54–71). NZCER Press.

Ministry of Education. (2017a). Te Whāriki. He Whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa Early childhood curriculum. https://tewhariki.tahurangi.education.govt.nz/early-childhoodcurriculum-home

Ministry of Education. (2017b). Te whāriki a te kōhanga reo. Te Whāriki Online.

https://tewhariki.tki.org. nz/mi/te-whariki-a-te-kohanga-reo/

Mitchell, L., Bateman, A., Kahuroa, R., Khoo, E., Rameka, L., Carr, M., & Cowie, B. (2020). Strengthening belonging and identity of refugee and immigrant children through early childhood education. Teaching & Learning Research Initiative.

Mitchell, L., Cowie, B., Clarkin-Phillips, J., Davis, K., Glasgow, A., Hatherly, A., Rameka, L., Taylor, L., & Taylor, M. (2015). Continuity of early learning: Overview report on data findings. Education Counts. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/continuity-of-early-learning-data-findings

Moss, P. (2006). Structures, understandings and discourses: Possibilities for re-envisioning the early childhood worker. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 7(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.2304/ ciec.2006.7.1.30

Moss P. (2011). Democracy as first practice in Early Childhood Education and Care. In R.E Tremblay, M. Boivin, and R. DeV. Peters (Eds.), J. Bennett (Topic Ed,), Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/child-care-early-childhoodeducation-and-care/according-experts/democracy-first-practice-early

Ng, O., Lees, J., & Kahuroa, R. (2023). Hidden stories of our landscapes: Walking and mapping the land with children. Early Childhood Folio, 27(2), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.1125

Oberhuemer, P. (2005). Conceptualising the early childhood pedagogue: Policy approaches and issues of professionalism. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 13(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930585209521

Park, G. (1996). Ngā Uruora: The groves of life: Ecology and history in a New Zealand landscape. Victoria University Press.

Penetito, W. (2001). If only we knew … Contextualising Maori knowledge. In B. Webber & L. Mitchell (Eds.), Early childhood education for a democratic society: Conference proceedings (pp. 17–25). New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Penetito, W. (2009). Place-based education: Catering for curriculum, culture and community. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 18, 5–29. https://doi.org/10.26686/nzaroe.v0i18.1544

Postlewaight, G., Cooper, G., & Burns, E. (2023). Early childhood teachers partnering with teacher educators to connect children to taiao (the natural world) through place-based learning. He Kupu: The Word, 7(3), 48–60.

Reedy, T. (2019). Tōku rangatiratanga nā te mana mātauranga: “Knowledge and power set me free …” In A. C. Gunn & J. Nuttall (Eds.), Weaving te whāriki, Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum document in theory and practice (3rd ed., pp. 25–44). NZCER Press.

Salmond, A. (2014). Tears of Rangi. Water, power, and people in New Zealand. Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4(3), 285–309.

https://doi.org/10.14318/hau4.3.017

Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust. (2020, April 3). Wererou te whāriki tuatahi [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DIca3jDUvrI

Walker, R. (2011). Design-based research: Reflections on some epistemological issues and practices. In L. Markauskaite, P. Freebody, & J. Irwin (Eds.), Methodological choice and design: Scholarship, policy and practice in social and educational research (pp. 51–56). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8933-5_4

Research team

Linda Mitchell is Honorary Fellow, University of Waikato. Her recent research focuses on early childhood education policy, democracy in education, refugee and immigrant families’ belonging through early childhood education, and place-based education. She is a strong critic of marketisation and privatisation in early childhood education and an advocate for reconceptualising early childhood services as a public good. Email: linda.mitchell@waikato.ac.nz

Bronwen Cowie is a Professor of Education, Division of Education, University of Waikato. Her research interests span science education, culturally responsive /place-based pedagogy and assessment for learning in early childhood, primary and secondary contexts. She values collaboration with teachers as part of the research process. Email: bronwen.cowie@waikato.ac.nz

Raella Kahuroa is a lecturer in the Division of Education, University of Waikato, and comes from a teaching background in early childhood education. Her research focuses on democratic practices, teaching and learning with refugee and immigrant children, and using critical thinking approaches. Email: raella.kahuroa@waikato.ac.nz

Hoana McMillan (Ngai Te Rangi, Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Kahungunu) is an education lecturer at the University of Waikato. A kōhanga reo graduate, she specialises in research related to this area. Her recent work focuses on assessment, and the influence of kōhanga reo on the educational success of whānau. Email: hoana.mcmillan@waikato.ac.nz

Teacher/kaiako partners

Maunganui Kindergarten: Catherine Rolleston, Abbey Collins, Karen Attrill, Letitia

McFarlane, Sam Owen, Nicola Jones (teachers). Pakuranga Baptist Kindergarten:

Jacqui Lees (director), Nilma Abeyratne, Danielle Rollo, Olivia Kwok Yee Ng (teachers).

Te Kōhanga Reo ki Rotokawa: Tiria Shaw, Heather Patu (kaiako).