| They don’t really see what School was like for me They only see what the Teachers see. What the teachers want Them to see. |

| You’re only telling your own story What school was like for you That’s easy coming from me. They need to know from The experience of what We see. Not what they see. What we see. |

| The voices of rangatahi in Alternative Education from Phase 1 focus group |

Introduction

Every year, at least 2,000 rangatahi, aged 13 to 16, continue their learning in Alternative Education (AE) settings, disenfranchised from mainstream schooling through exclusions, multiple suspensions, or truancy. Of this population, 68% are Māori and 17% are Pasifika (Education Review Office, 2023). The high numbers of Māori in AE reflect that schools in Aotearoa stand down, suspend, and expel more Māori students than any other ethnic group (Education Counts, 2021).

For many rangatahi, AE is their last formal education opportunity. Only 25% of rangatahi return to school immediately after leaving AE, with more than half not continuing schooling, further training, or employment (Education Review Office, 2023). While a series of factors, such as health needs, socioeconomic status, and family circumstances, may contribute to a referral to AE (Education Review Office, 2023), schools can aggravate these factors (Sutherland, 2016). An earlier study that elicited the voices of 41 rangatahi in AE, found that “the main reasons for disengagement appeared to be firstly that students reported teachers as not knowing them or developing effective relationships with them, and secondly … a mismatch between their levels of achievement and teaching levels” (Brooking et al., 2009, p. viii).

Rangatahi often enter AE with significant gaps in their learning, and scarce information about their past schooling experiences and achievement. The teachers and rangatahi must make a fresh start, leaving past successes and challenges unaddressed. In some instances, the lack of historical records has led to rangatahi, whānau, and teacher puzzlement and powerlessness regarding how rangatahi ended up in AE (Schoone, 2016; Smith, 2009). It has also delayed or prevented rangatahi from receiving additional education support (Education Review Office, 2011) and created a barrier to meaningful critical engagement with the rangatahi to interrogate the systemic levers of school disengagement. Perhaps more pressing is that disengaged rangatahi from formal education have not felt listened to or had their insights taken seriously by those in authority (Thomson, 2007). In a focus group in preparation for this research, rangatahi were adamant about wanting their stories to be known to teachers, principals, boards of trustees, and the Ministry of

Education. On having the opportunity to tell his story, one rangatahi stated that he would feel “cared for”.

Our focus

This research shed light on critical moments from previous education and schooling experiences of rangatahi in AE. Critical moments are events that have had “important consequences for their [the students’] lives and identities” (Thomson et al., 2002, p. 339). This central research aim was couched in a broader methodological research remit to understand how teachers in AE could work with rangatahi to tell their stories, and what this could mean for their teaching practice. Therefore, the research also provided the AE workforce with an opportunity to bring their expertise to the fore. This research asked:

- How can teachers inquire about critical moments from the past experiences of rangatahi in the formal education system?

- What can schools learn from the insights gained from this inquiry to improve education experiences for vulnerable rangatahi?

- How can this knowledge inform teachers’ planning and pedagogy?

Two AE managing schools were recruited in Auckland: Mount Albert Grammar School and Green Bay High School and their respective AE consortia: Auckland City Education School and Waitakere Alternative Education Consortium. The idea to research within AE initially derived from conversations held between academic researchers who had research interests in AE and Auckland-based AE consortia co-ordinators. At one meeting, held between the COVID lockdowns in Auckland, one response to the provocation of “What would we most want to know now?” one AE co-ordinator remarked: “We want to know the stories. The stories of our young people.” After ethical approval, Mount Albert Grammar and Green Bay High School were invited to participate. It is important to note that the managing schools provide the administrative responsibility for AE, but the schooling experiences of rangatahi derived from multiple schools at all levels. Due to the importance of relationship and trust, rangatahi in AE were invited to participate through the school AE co-ordinators. In total, 10 teachers and 20 rangatahi in AE contributed directly to the action research (AR) alongside four academic researchers. Present and past AE Consortium managers contributed in an advisory capacity.

Methodology and methods

Conceptual design

AR was adopted as the overarching methodology. AR is a widely accepted inquiry learning approach, combining both research and practice, with popularity in the education sector (Adelman, 1993; Carr & Kemmis 2005; Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988). The potential for personal, team, organisation, and community improvement/transformation is well reported (Piggot-Irvine et al., 2021). For this project, we conformed to the view that:

AR is a collaborative transformative approach with joint focus on rigorous data collection, knowledge generation, reflection and distinctive action/change elements that pursue practical solutions … Put another way, we defined AR as having core elements of systemic research in a collaborative inquiry process that is associated with evidence-based decision making both before and after change. (Piggot-Irvine et al., 2021, p. 14)

The AR approach aligns with best practice for professional development in the AE sector, namely the highly collaborative approach in which there is “privileging of internal ‘within sector’ knowledge” (Bruce, 2020; Plows, 2017, p. 72). The relational, collaborative, interactive underpinning of AR has been crucial in giving voice to rangatahi and AE teachers. Reflecting the relational basis of AE, it essentially was a project about enhancing those relationships using an AR project drawing upon relationships throughout the entire approach. For example, rather than academic researchers working directly alongside rangatahi in the story inquiries, AE teachers who were known and trusted by rangatahi were instrumental in developing an empathetic approach. AR is, overall, an inquiry approach with deliberate reflective elements. To aid teachers’ reflection in and on action, the team followed Gibbs’ (1988) cyclic approach, attending to description, feelings, evaluation, analysis, conclusion, and action. Teachers reflected in action through online blogging and learning conversations with academic coaches, and teachers reflected on action through formalised presentations to the research group at the end of e 3ach cycle.

Action research phases/cycles

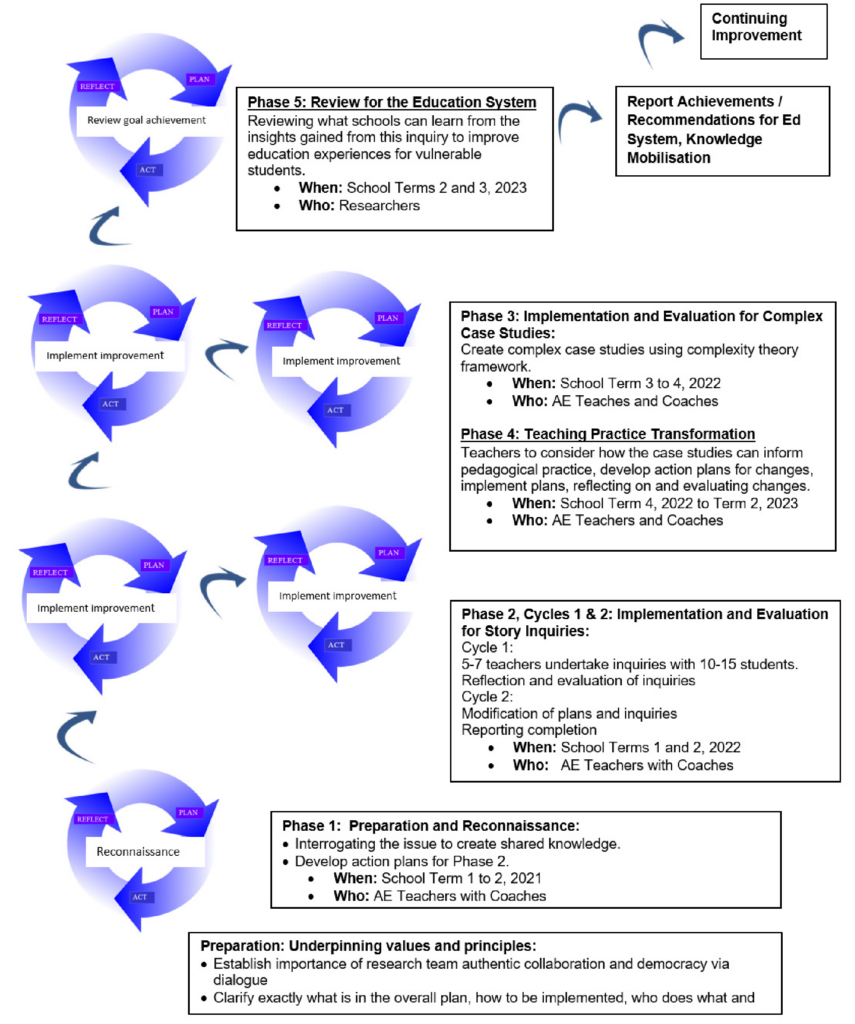

The following AR phases were employed (Figure 1):

- Phase 1: The preparation and reconnaissance phase explored the tentative research question, provided professional development to assist teachers with setting up their individual inquiries, and sought the perspectives of rangatahi on the AR intent and design. Importantly, Phase 1 was about bringing the research group together through a shared vision.

- Phase 2: Teachers implemented their inquiries with rangatahi over two cycles. Teachers were coached by academic researchers during the implementation and at two points presented their inquiry findings to the whole group. The inquiry methods chosen by each teacher comprise substantive research findings described in the next section.

- Phase 3: Fifteen stories collected by the teachers were collated, and case studies were developed for each story. In addition, a thematic analysis across the stories was undertaken to understand common experiences. Attention was given to how the stories were to be re-presented.

- Phase 4: A new teacher inquiry phase was instigated. Based on the collected stories from Phase 2, teachers planned pedagogical improvements for rangatahi in AE settings.

- Phase 5: In surveying the data from the previous four phases, Phase 5 focused upon recommendations for the education system, including for schools and teachers.

FIGURE 1: AE stories AR overview

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was gained by Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (AUTEC). From the outset, we have sought to safeguard vulnerable rangatahi from feeling they are expected to divulge every trauma they have experienced through the education system, and equally that teachers and academic researchers are expected to interrogate rangatahi for every last detail. The Participant Information Sheet reads “This is not a ‘tell all’. Just share what you are comfortable with sharing. These may be challenging or positive moments.” In support of this approach, we adopted the whakataukī (Māori proverb), “Ahakoa he iti, he pounamu” (Although it is small it is precious). AE staff members were instrumental in assisting by talking through the consent process with rangatahi and connecting with whānau to gain consent for rangatahi under 16 years of age. At times, this included calling in to see whānau during the van runs when dropping rangatahi home.

COVID-19

This research was undertaken over the period of New Zealand’s most acute phase of the Coronavirus epidemic. Significantly, when Auckland went into Level 4 lockdown from 17 August 2021 and remained in restrictive Level 4, then Level 3 measures until 2 December 2021, resulting in a 107-day lockdown. The time frame adjusted accordingly as data collection of rangatahi stories did not occur online due to constraints with IT equipment and data/Wi-Fi capability, and concerns about engaging in remote conversations regarding potentially challenging topics on school experiences.

Overview of research participants

| Name | Ethnicity | Gender | Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kane | European/Pākehā | Male | 15 |

| Carlos | Māori/Pākehā | Male | 16 |

| James | Māori/Cook Island | Male | 15 |

| Mafa | Tongan | Male | 15 |

| Tala | Tongan | Male | 15 |

| Atawhai | Samoan/Niuean | Female | 16 |

| Mike | Samoan/Niuean | Male | 14 |

| Avontales | Samoan | Male | 15 |

| Jaydan | Samoan | Male | 15 |

| Jonathan | Samoan | Male | 15 |

| Junior | Samoan | Male | 16 |

| Loimata | Samoan | Female | 15 |

| Ardie | Samoan | Male | 19 |

| Benjamin | Cook Island/Samoan | Male | 18 |

| Kobe | Cook Island/Māori | Male | 15 |

Note: Names are pseudonyms.

| Age | 14, 15(9), 16(3), 18*, 19**

*One past AE rangatahi participated |

| Ethnicity | Samoan (6), Samoan/Niuean (2), Pākehā, Tongan (2), Māori/Pākehā, Māori/Cook Island, Cook Island/Samoan, Cook Island/Māori |

| Gender | Male (13), Female (2) |

| Research phase | Number of teachers |

|---|---|

| 1 | 2 |

| 1–3 | 2 |

| 1–5 | 2 |

| 3–5 | 1 |

| 4–5 | 3 |

Key findings

We recognise the complex nature of findings in AR can potentially contribute to both continuing action and theory (Kemmis, 2010). For clarity, our research contributes to: 1) methodological understanding, “How can teachers inquire about critical moments from the past experiences of rangatahi in the formal education system?”; 2) substantive insights, “What can schools learn from the insights gained from this inquiry to improve education experiences for vulnerable rangatahi?”; and 3) understanding practice, “How can this knowledge inform teachers’ planning and pedagogy?”

RESEARCH QUESTION 1:

How can teachers inquire about critical moments from the past experiences of rangatahi in the formal education system?

I feel confident and hungry to research! I feel as though this can make a huge impact on education. (AE teacher)

Teacher development sits at the heart of this AR (Schoone et al., 2022a). In early 2021, the principal investigator presented an overview of the research at staff meetings within the respective AE settings. Initially, six AE teachers volunteered to participate; four worked within the same AE centre which operated across two different localities in Auckland. Of the other two teachers, one worked within a school-based centre, while the other was employed in a school-run offsite centre. AE teachers imagined AR as a complex, critical inquiry and learning approach that draws from cultural and personal identity. Through an analysis of recorded interviews with teachers, teacher blogs, and written teacher reflections, we found the following AE teacher approaches were enablers of authentic inquiry with rangatahi: valuing AR as a learning process; finding relevant points of entry; and taking a critical stance.

AE teachers valued AR as a learning process

Teacher feedback from the Phase 1 professional development workshops highlighted that, prior to the research project, no teacher was familiar with the term “AR”. The professional development evaluation responses, and subsequent inquiry planning, are testament to the strides they have made in learning. Further, several teachers became international authors through reporting their findings (Fair et al., 2023). Teachers commented on becoming aware of “authenticity, agency, ethics, and focusing on process as opposed to just outcomes”, “infusing art to activate storytelling”, and “working within an understanding of culture”. One teacher participant was relieved to find “[AR] is somewhat guided and supported which puts my mind at ease”.

AE teachers found points of entry relevant to their personal experiences and the cultural needs of rangatahi

In forming their AR approach, teachers in AE drew from their cultural identities and personal interests and took examples and experiences from popular culture (such as inspirational movies). As outlined in the following section on inquiry methods, as teachers worked predominantly with Pacific rangatahi, many inquiries included Talanoa, a Pasifika cultural concept for conversation (Vaioleti, 2006). Adopting Talanoa did not preclude teachers of European ethnicity integrating this approach. Rather, it provided an opportunity for teachers to be critically reflexive. For example, one teacher came to the realisation that it was the relational values he brought to the conversational approach rather than feeling pressure to follow a fixed cultural form.

AE teachers took a critical stance

Implicit to the AE teachers’ inquiry approaches was a radical openness to listen to rangatahi, even when they challenged the teaching profession. A critical inquiry approach is in keeping with and widely reported in AR (Coghlan & Brydon-Miller, 2014). AE teachers demonstrated critical awareness of the social, political, and historical influences upon the lived experiences of rangatahi in education. For example, the teachers observed “It’s got a lot to do with colonisation … [We have] a system that was actually built for Māori not to succeed”; “The Western system of education is built around the … theoretical”, and “Mainstream education doesn’t present the best way to learn.” The social justice values central to AE teachers’ outlook filtered through various aspects of their planned inquiries. For the AE teachers in this study, their motivation has been to “fix” the system rather than a focus on “fixing” rangatahi.

Inquiry methods

As a result of these AR enablers, the teachers did not shy away from co-constructing with rangatahi complicated inquiries and engaging in multiple layering of actions in Phase 2. The inquiries became complex as they were developed with reference to specific learning challenges in AE settings (such as the transitory nature of student population), preferred pedagogies (such as relational and hands-on approaches), ethical matters (being careful not to single out rangatahi, providing ways to present stories confidentially, and respecting the sovereignty of knowledge), cultural considerations (such as use of appropriate methods), and the COVID pandemic health requirements. The following inquiry methods were adopted by the AE teachers (see Fair et al, 2023, for a comprehensive outline).

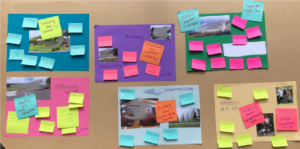

FIGURE 2: AE rangatahi photo storyboard, AE rangatahi journal writing, photo from “go-along” interview

|

|

|

|

||

Photovoice

One teacher used a photo-elicitation technique—a favoured mode of expression for youth (Croghan et al., 2008). The teacher wanted to create something collaboratively with rangatahi to represent their educational journey. Interviews with rangatahi were conducted using images from their early childhood education centres, primary, intermediate, and secondary schools as prompts (Figure 2). The questions and discussion became about the memories and moments provoked by the photos. The photos helped to spark in-depth discussion and reflection.

Journal writing

The method of journal writing was undertaken by one teacher who, after watching and being inspired by the film, Freedom Writers (Gruwell, 1999), felt that the use of journaling would be a non-invasive way for rangatahi to express their thoughts and ideas without restriction. The teacher explained “I wanted to provide the students with an opportunity to openly and honestly share about, and release, their educational journeys while also self-reflecting on their journey and growing as individuals during the process.”

Talanoa

In the Phase 1 focus group, we asked rangatahi about methods of inquiry for this research project. One rangatahi stated “I would just talk with someone that I can trust.” Talanoa, a Pacific practice of two-way conversation (Fa’avae et al., 2016), became a central method in many of the teachers’ inquiries. In talanoa sessions, rangatahi had individual and small-group discussions with their teacher. The following quote is from one of the participants:

For me, I enjoyed sharing my experiences though the talanoa process. I really liked that we talked about my story rather than writing it down because it felt like a conversation rather than like an exam. I have never got the opportunity before to speak freely about the situations that happened but more importantly explain how I felt. This talanoa has given me open ears so that my voice has an opportunity to be heard. It felt really cool to be a part of this, it made me feel important and that somewhere my story could be making change.

“Go-along” place-based interviews

The “go-along” interview approach blended photos, place-based reflection, and a commentary about the memorable moments in mainstream schooling before the rangatahi was excluded and joined AE (Carpiano, 2009). The teacher explained that, in working with one rangatahi, “instead of doing a formal interview, we had a ‘catch-up’, shared food, and checked out places related to his upbringing and education around the neighbourhood where he lived”. Localities brought up memories of good times spent with friends, and places where they bought and shared food (Figure 2). Visiting the school from which the rangatahi was excluded allowed him to reflect on specific highlights and lowlights from his journey in education and the “exclusion” moment in time and context.

In conclusion, the multiple methods used were successful in giving voice to rangatahi. The approaches were interactive, compassionate, and enabled responsiveness from rangatahi. The employment of distancing strategies, such as food, photos, and photo boards, writing, and go-along experiences, provided a safe and conducive environment for sharing experiences. These served as “a mediating tool” between rangatahi, the AE teacher-researchers, and their experiences, and enabled rich conversations (Niemi et al., 2015). Additionally, knowing rangatahi, or having a previously established relationship based on empathy, care, and acceptance, helped put rangatahi at ease. As one rangatahi told us in the Phase 1 focus group, “It’s hard to trust people nowadays, aye … It’s hard to trust … If you hear about our stories, then you understand what I mean.”

Results of teachers’ inquiries

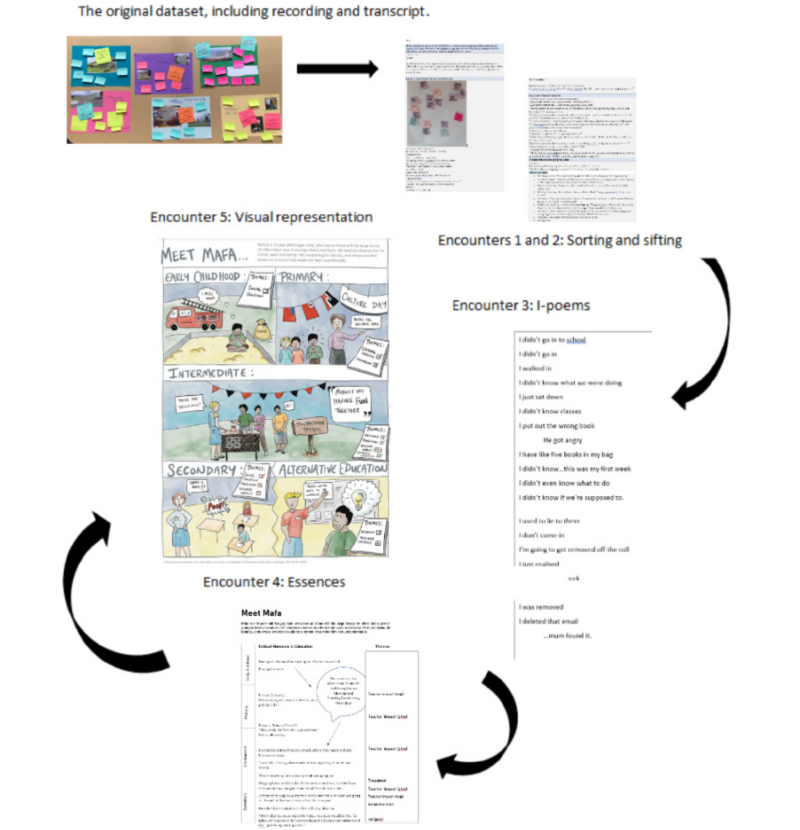

In total, 15 stories from AE rangatahi were collected. To report on insights gained from the stories, a cyclical process of encounters with the data from each of the teachers’ inquiries aided the development of individual rangatahi case studies and the analysis of themes deriving from across case studies. In essence, the critical moments were co-constructed between the rangatahi and teachers, with academic researcher input. Each encounter with data sought to gain progressive insight based upon the original collected data (Figure 3). We have described the co-constructions as “Encounters”.

FIGURE 3: Cyclical process of creating case studies

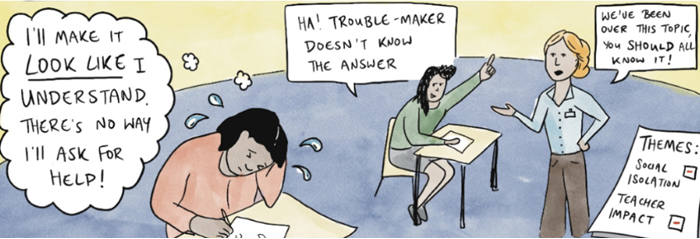

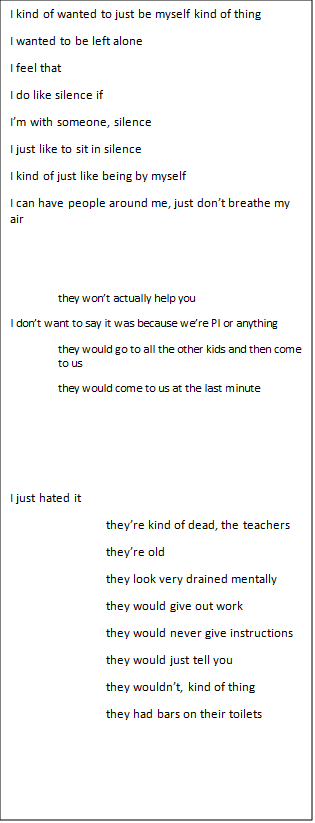

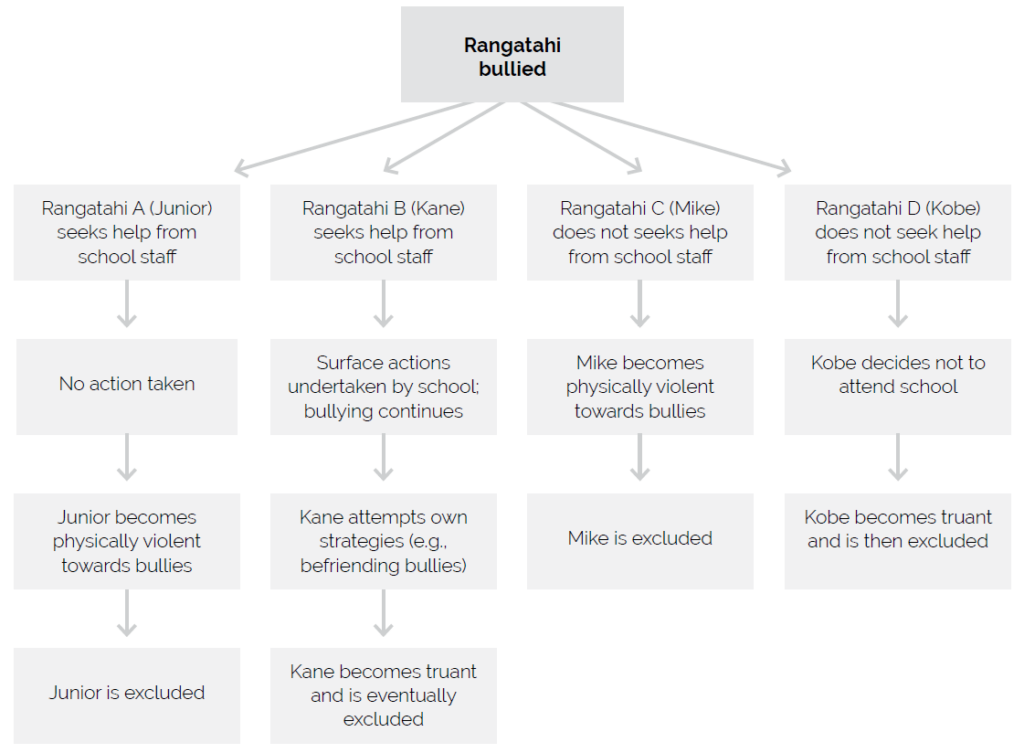

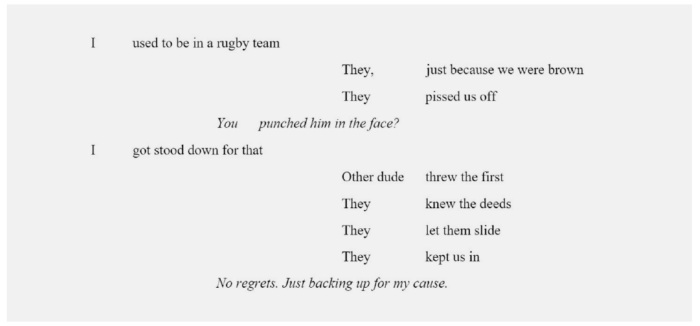

From the original data set in Encounters 1 and 2, the academic research team and AE teachers, with input from research advisory members, read through each of the transcripts to identify themes. The transcripts were read multiple times by members of the research team. As shown in Figure 4, with Encounter 3, “I” poems were written from transcripts (Schoone et al., 2022b). Woodcock (2016) explains the I poem enables a “systematic way for researchers to listen to an informant’s first-person voice … and hear how informants speak to themselves in relationship to themselves and others” (p. 4). Encounter 4 resulted in the creation of storylines for each rangatahi with a corresponding “I” poem. Encounter 5 involved employing a graphic designer to re-present seven of the storylines in cartoon form (see appendices). The purpose was to re-see the stories from a fresh perspective, to provide an aesthetically engaging resource for a wider audience, and a further distancing mechanism to mediate the experiences of rangatahi through cartoon form.

FIGURE 4: I poems developed from Atawhai’s research transcript

RESEARCH QUESTION 2:

What can schools learn from the insights gained from this inquiry to improve education experiences for vulnerable students?

In this section, we discuss the meta-narrative, comprising themes that have emerged from across all 15 stories. Rangatahi have critical insights into the education system and these insider perspectives should be privileged when it comes to school improvement considerations. As Bourke and Loveridge (2018) assert, “in order to take student voice seriously, the system (policy and practice) that children learn in must radically change through listening and acting on their views, and position student voice as political and educational imperatives” (p. 1). Through sharing their stories, three themes emerged including the role of microaggressions and microaffirmations; the role of the social and cultural in education spaces; and the role of pedagogy on rangatahi engagement.

The role of microaggressions and microaffirmations

While the case studies were analysed for critical moments, there was often no single defining moment. As Sutherland (2016) found in an earlier study on youth offenders’ formal schooling experiences, “the cumulative effect of negative school experiences” (p. 115) could lead to their alienation from the school system. Additionally, Reimer and Longmuir (2021) found that students in AE in Australia were victims of microaggressions:

Microaggressions are the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons solely upon their marginalized group membership. (Sue, 2018, p. 22)

It appears that the path towards AE in New Zealand is also paved with microaggressions. The insidious nature of microaggressions means that single incidents may not be remarkable, or be in themselves cause for concern, but have a cumulative, and therefore, negative impact. The microaggressions acted as affective forces upon students’ feelings. They shaped and reshaped identities, often culminating in a “crisis … in the ordinary” (Berlant, 2011, p. 10). The following rangatahi quotes are examples of microaggressions:

| “I was always in the lowest [reading group] and that really made me feel insecure … it was like a put down.” (Ardie)

“[The secondary school teacher] is always noseying in your problems.” (Carlos) After two weeks absence, “So I just sat down and they were like ‘where’s your book’!? … Oh, wow, ok.” (Mafa) “[The teacher] got angry with me … I didn’t know if we’re supposed to draw what [the teacher] was drawing on the board.” (Mafa) “I felt left out [by the teacher].” (James) “[The teacher] was just real strict and harsh … You made a mistake, [the teacher] will call you out like in front of the whole class.” (Ardie) “[Students were] mocking me. They were like, ‘oh, it’s the anger issue’, and they kept going on.” (Kobe) “When I hang out with White people I am too Islander for them, but when I hang out with Island people I am too White for them.” (Atawhai) “When someone says something mean to you your brain’s automatically going to feel bad.” (Kane) “When I was walking around, it was like, ‘watch out, there’s the troublemaker’.” (Loimata) “I feel like … [having been] prejudged, but not all teachers were like that though, but I just feel most were.” (Ardie) |

Reimer and Longmuir (2021) state, “the persistent experience of microaggression requires persistent counteraction to dispel its effects” (p. 74). They cite microaffirmations as the “small things” that provide positive experiences and a humanizing effect on students (Reimer & Longmuir, 2021, p. 74). While micro-affirmations were evident in the rangatahi narratives, they were not as prevalent throughout their schooling experiences. “She [the teacher] was chilled about the things I did at Intermediate.” (Jaydan)

| “They made me feel like I was welcome [in Primary School 2].” (Mafa)

“Every time [the teacher] knew I was stuck on something, [the teacher] like actually came and saw us.” [Secondary school] (Mafa) “There was one teacher, my Samoan teacher … [they were] really nice. [The teacher] would sit there and encourage me.” (Loimata) “[The teacher] really believed in us … it gives you a little bit of hope and that’s all it took.” (Ardie) |

The role of the social and cultural in education spaces

School environments are not merely “containers or backdrops” where learning occurs; they are “social spaces that ‘produce’ and ‘reproduce’ models of social interactions and practices while also mediating the relational and pedagogical practices that operate within” (Baroutsis et al., 2017, para. 13). We found that the social and cultural aspects of school accounted for a large proportion of critical moments identified in rangatahi stories.

Navigating sexuality, being a new immigrant, absence from school for long periods, having a “teacher aide”, and volatile friendships were mentioned as impeding social relationships within school. However, having a positive friend group undoubtedly increased enjoyment in school and acted as a protective factor. Of the 15 stories, a third of rangatahi, all male, talked about being with “the boys”. They wanted to be together in class, and in break times (for example, playing manhunt). Allied with friendship groups at school was the importance of somewhere to hang out together. When one school prevented this, it had a detrimental impact upon the sense of belonging at school for rangatahi.

Across the 15 stories, we found that bullying, transition, transience, and the various forms of exclusion within schools accounted for critical schooling moments. We summarised the key insights from each of these critical moments as follows.

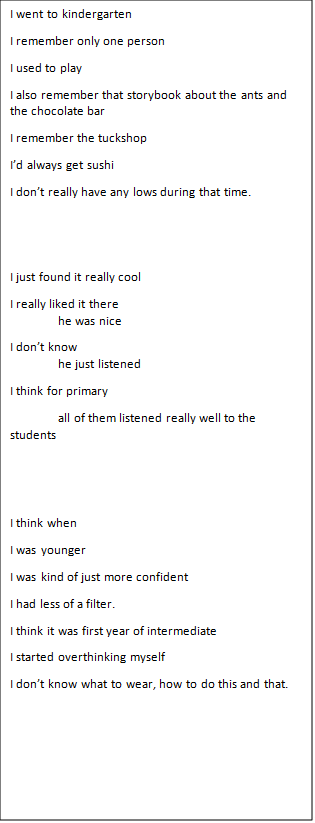

Rangatahi in AE settings as first victims of bullying

Based upon the entry requirements for AE, it could be assumed that AE rangatahi are the sole perpetrators of bullying. We only found one rangatahi who bullied other students in their previous school/s without first being a victim of bullying. Of the remaining 14 rangatahi, however, four disclosed being victims of bullying at school. In a health survey of 91 students in AE, 8% reported they were bullied about once a week when they were in school (Clark et al., 2023). Each of the bullying incidents represented in Figure 5 shows four trajectories that all resulted in negative outcomes for rangatahi.

FIGURE 5: Flow chart showing rangatahi experiences of bullying

Transition and transience

Transition between education institutions is a complex social maneuvering. Many rangatahi in AE have undergone multiple school transitions (Education Review Office, 2023). For example, Junior attended four primary schools, Mike had also attended multiple primary schools and did not attend intermediate school, while James attended three secondary schools. Specific transition challenges rangatahi faced included missing the first few weeks of Year 9 (Mafa, Loimata), and other rangatahi discussed the difficulties of adjusting to the secondary school environment:

You step into a space where there’s 1,000 students and all of a sudden, it’s all new people, teachers, classmates, peers and you feel like … you have to start all over again … There’s a thing called detention! (Ardie)

Benjamin spoke of the challenge of transitioning from AE into mainstream school, “It was pretty overwhelming. Like it’s like going from like, 0 to 100 … the work was like so much like so much, actual like real challenging stuff we have to do, and more strict as well.”

In-school exclusion

FIGURE 6: Avontales sent to the in-school withdrawal room

The manipulation of the social space occurs in some schools through the use of internal suspensions, withdrawal rooms, thinking spaces, and time out in senior staff member offices. Loimata described how she was lonely through school, and that in primary school she “had to be in the office 24/7” to do a “think sheet”. Avontales recalled the use of a withdrawal room in his secondary school (Figure 6), “It was just like jail. Just like prison … when you look outside the window you see everyone having fun.” Rangatahi reported being sent to the withdrawal room for up to 10 days (Avontales, Jaydan). Jaydan recalled being sent out of class to the withdrawal room for placing his hands under the table; presumably, the teacher thought he was hiding contraband. The teacher yelled, “out out out out!”. Tala felt the withdrawal room “just made me angrier and angrier”. Not only did the withdrawal room socially isolate students, but it provided poor learning opportunities.

Choosing not to attend formal education

Rangatahi removed themselves from formal education for multiple reasons. At secondary school, Carlos explained that the school “were going to kick me out, but then mum didn’t want that on my record, so she just took me out”. Mafa explained that because the teachers were “mean”, he wagged every Monday and Tuesday. The school intervened and changed some of his classes, but eventually he became a chronic truant. Loimata began missing school and since primary school has been labelled as a “troublemaker”, having been blamed for incidents at school. During Year 8, James was peer pressured not to attend school but to “chill in my mate’s garage”. At secondary school, because the dean was constantly “picking on him”, he chose not to attend, which ultimately resulted in exclusion. Mike was unable to get an enrolment in intermediate school, so was absent from formal schooling for 2 years. Atawhai shared that, at secondary school, “I knew I wasn’t going to get any help, so I just didn’t bother showing up.” Central to all these anecdotes is the role of the social milieu and the central importance of relationships that have either enabled or discouraged school engagement.

The role of culture in education

I poem—AE rangatahi from focus group

Cultural identity appeared critical to AE rangatahi wellbeing, belonging at school, and engagement with learning. Many of the rangatahi in our study were Pasifika (87%) or Māori (20%)[2] which aligns with the high numbers of rangatahi from these ethnic groups excluded from mainstream secondary schools each year and referred to AE (Education Review Office, 2023). Existing research has found that a positive ethnic identity for Māori is associated with positive outcomes and may be a protective factor when rangatahi face negative or challenging schooling experiences (Cliffe-Tautari, 2020; Webber, 2012; Webber & Macfarlane, 2020).

When rangatahi in our study talked about their cultural identity, they referred to the positive and negative ways they were viewed by others or themselves. One rangatahi who felt positive about his ethnicity stated, “I’m a proud, New Zealand-born Samoan … It’s always played a big part in my life, especially in everyday choices that I have to make” (Ardie). Another rangatahi pointed to cultural events as the highlight of his schooling. These were rare times in his education that he associated with fun and belonging (see Figure 7): “We had the culture day … Everybody would come in the dress of that culture. I think those were like, really cool … The students did a market day. My group made Polynesian treats … I got my mum to make some …” (Mafa).

FIGURE 7: Culture day at Mafa’s intermediate school

Some rangatahi also felt pre-judged or were viewed negatively because of their ethnic group or skin colour: “… being brown, sometimes you’ve already got a record because of past students … The teachers would be like, ‘Oh yeah, okay, got a Polynesian student here. I might have to keep an extra eye on them’” (Ardie). Another rangatahi said that she and other Pasifika students were unsupported or ignored by their teachers:

I did ask for help a lot but they won’t actually help you … I don’t want to say it was because we were PI [Pacific Island] or anything, but they would go to all the other kids and then come to us. (Atawhai)

For some rangatahi in our study, who already felt like they did not fit in, their ethnicity was another way they felt different to other students in their schools: “The school was full of lots of palagis. Me and my sister were the only Samoan there … All the white kids would look at us when we walked past” (Loimata). Ardie and his friends were asked by a deputy principal in one school not to walk to and from school in large groups, presumably as it was intimidating for neighbours. Ardie explained “another deputy principal, he’s brown, and he said to us—look boys, I’m just gonna put it to you straight. It’s definitely because you are brown.”

The role of pedagogy on rangatahi engagement

Teachers make a difference. Rangatahi in our study referred to effective pedagogy and practices, such as:

- engaging activities in early childhood centres

- developing positive relationships with teachers in primary school

- teachers linking learning to culture

- the assistance of a teacher aide to help one rangatahi calm down

- treating all students equally regardless of their level

- teachers introducing themselves and providing help when required

- secondary deans intervening in rangatahi timetables, making class changes when necessary to aid engagement (such as changing teachers if there is an ongoing issue)

- teachers who saw the potential in rangatahi and held high expectations for learning

- learning that was active and motivating

- teachers who were funny and chilled and gave opportunities for rangatahi to learn with their friends (“being with boys”)

- schools providing food

- teachers conveying their happiness when the rangatahi returned after a long absence.

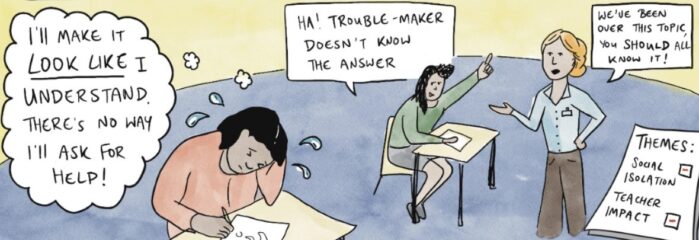

Across the 15 stories, we found the pedagogical challenges rangatahi faced centred upon teachers not providing sufficient scaffolding with learning tasks, particularly for rangatahi who had been absent from school and trying to catch up. Rangatahi did not feel confident asking for help or were embarrassed to show their lack of knowledge (see Figure 8). In addition, two Pacific rangatahi commented on the negative impact of being put in ESOL (English for speakers of other languages) or being given unchallenging work. For example, “I was in this class for extra support, but I already knew what I was doing” (Avontales).

FIGURE 8: Loimata’s classroom experience

Perhaps most significant was that rangatahi in this study did not receive an education that equipped them with emotional regulation skills. A number of rangatahi stated they had anger issues (Tala, Mike, Junior, James, Jonathan), with Junior stating that when one of his teacher’s left “I felt no one could put me back in line”.

Moreover, it appeared rangatahi did not find support for processing and healing from ongoing and past trauma beyond school, and other developmental needs. When Jaydan sought support from his school counsellor, he relayed that he was told to “get lost”. Carlos felt that his teachers didn’t care about the feelings and wellbeing of rangatahi, they “just wanted to teach and get the job done”. Rangatahi in AE had come from physically violent homes (Avontales, Jonathan, Junior, Mike, Kobe), had been subjected to physical abuse at school (Kane), had PTSD or early life trauma (Kane, Loimata), experienced gang influence (Loimata), had health issues (Atawhai, Carlos), had a parent in prison (Benjamin, Mike), experienced ongoing grief from losing a loved one (Kobe), and navigated sexuality and identity journeys (Atawhai, Mafa).

The role of AE as restorative

While reportedly the quality of AE provision may vary (Education Review Office, 2023), the Tomorrow’s Schools Independent Taskforce (2019) conceded that, for the most alienated and disengaged students, “alternative education may be the best short-term practical option” (p. 63). Entry into AE was fraught with difficulties for many rangatahi. For example, Loimata did not know why he was excluded; Mafa did not know he had been taken off the roll; and Avotales missed the exclusion meeting because a parent was at a hospital appointment.

Across the stories, AE was overwhelmingly a positive learning experience, despite some first impressions that it was for “bad kids” (Mafa), or “hood rats” (Junior). Rangatahi soon valued the learning spaces of AE, “rather than being trapped in a classroom all day” (Kane). Central to the success of AE were the teachers and tutors “who always encourage us” (Jayden) and provided effective pedagogy: “I think you guys explain it more …” (Mafa), contextualising learning to rangatahi interests and cultural backgrounds (for example, a study on the Polynesian Panthers). The tutors motivated rangatahi to attend, “I’ve got the tutors here, they help me a lot. I wanna come every day” (Kobe). In addition, tutors mentored rangatahi, “he’s like real to you … he’s not going to tell you what you want to hear” (Benjamin). However, Benjamin felt that AE “makes you feel more different than the other kids your age” and he wished AE was more like school to aid his return to mainstream secondary education.

AE was considered a safe place for many rangatahi. For example, Junior shared that it was a space where he could begin to change (Junior). Mike stated that in AE, “I’ve been getting more mature and changing, like changing how I deal with things.” Mafa stated, “I actually feel more welcomed [in AE].” For Atawhai, she felt like she could “open up here”. Time and time again, rangatahi spoke of AE as having a family environment, “we all respect each other and treat each other like family” (James). For Benjamin, AE was a place of sense making and healing.

Research Question 3:

How can this knowledge inform teachers’ planning and pedagogy?

A further inquiry was undertaken by six teachers in AE to explore how the stories impacted their teaching approaches (Phase 4). Two of the six teachers were original recruits from the beginning of the project, and four teachers were new recruits. By this stage, the original two teachers were conversant with AR processes and were immersed in the stories collected in the previous phase. For the new recruits, this was a chance to ascertain how teachers were impacted by engaging with rangatahi stories. As these teachers were “connoisseurs” of the AE context, they brought to their inquiries professional experience in the sector, and this gave them a refined “understanding of a domain that the meanings the individual is able to secure is both complex and subtle” (Barone & Eisner, 2006, p. 100.

On the basis of the stories, the following pedagogical shifts reported by teachers were implemented as follows:

- The stories were used as a professional development resource by one teacher to induct new teachers into the AE so they could understand the lived experiences of their rangatahi prior to entering. The basis of his inquiry was, “knowing what we know, what can we do in our practice to support the students?” A staff meeting discussing one of the stories resulted in raising awareness of the need for trauma-informed professional development.

- One teacher inquired into the explicit teaching of emotional regulation in the classroom. Initially, the teacher sought an off-the-shelf curriculum, but decided to focus upon “just in time” (teachable moments) that occurred on the spot.

- One teacher intentionally made space for rangatahi to connect with their culture through an informal cultural assessment. Over the course of the implementation phase, the teacher held face-to-face talanoa [conversations] with five rangatahi based on the theme of “Ko wai au?” [Who am I?]. Her inquiry found that rangatahi desired to learn more about their culture and language but lacked the know-how about where to next. The data from her inquiry are now the basis for planning cultural programmes in the AE centre, using expertise from the community.

- Strengthening the transition processes into AE became the focus for one inquiry. Throughout this inquiry, one teacher consulted with those responsible for transition into AE, and also sought rangatahi voice. He found that, “The FIRST moments we have with a student are crucial.”

- One teacher was impacted by how the stories allowed space for rangatahi to talk about their schooling experiences. Her inquiry focused on her questioning skills with rangatahi to give room for extended conversations in the classroom.

- Finally, one teacher sought to understand from rangatahi perspectives, their barriers to learning in AE settings, asking, “WHY learning was one of the very last things rangatahi wanted to do in AE.” His inquiry focused on noticing everyday behaviours and needs of individual rangatahi (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9: PowerPoint slide from AE teachers’ inquiry into practice

In summary, through this inquiry the stories collected by the AE teachers became prismatic, in that they cast light in various directions for inquiry suitable to each of the teacher’s context. The stories were a rich source for teacher development and ongoing inquiry. Phase 4 also mirrored some of the AR enablers we found in Phase 2: valuing inquiry as a learning approach, reflecting culture, and taking a critical stance. Due to time constraints, owing in part to compressed time frames as an impact of COVID, Phase 4 provided a snapshot of what is possible with narratives. We recognise that effecting pedagogical shifts entails a long-game and is fraught with many additional professional development constraints within the AE sector (Bruce, 2021).

Implications for practice

There is a lot more than just a bad kid who doesn’t care about school. I think there is more to that … teachers don’t understand that … if they got to know me before I got expelled, they would have realised like, I was just like, … a good kid in a bad situation. And I feel that they didn’t take that into consideration. I know it was my actions, but I feel like it shouldn’t have been enough to, you know, end my whole future, basically. That was my future, and they don’t think about that. They just thought about this kid. He did wrong. He should be punished. But not why did he do wrong, how could we help him not to do this? (Benjamin)

Benjamin’s kōrero provides the essence of rangatahi experience and gives a steer on implications for practice from this study. Firstly, Benjamin mentioned, “I do feel if they got to know me before I got expelled, they would have realised”. Rangatahi stories indicate that they were asking for understanding while at school. “Stop assuming, aye … stop assuming” as Carlos implored.

This research provided an opportunity for teachers in AE to explore with rangatahi their schooling stories though an AR structured approach—for rangatahi to “be heard”. In the main, the education system listens and responds to dominant voices in a language it knows. Rangatahi have been on the pointy edge of schooling discourse, with words like “detention”, “non-attendance”, “withdrawal rooms”, “standdowns”, “exclusions”, and “failure”. Jones and Spector (2017), working with disenfranchised students, share the ways in which trauma, shame, and affect circulate around students’ lives so powerfully that, “they have acquired these nuanced trauma-filled literacies so well in their bodies that their encounters with the ideas flow through them affectively and pour out of them in undeniably bodily ways” (p. 311).

The language of AE rangatahi is marginalised. When rangatahi are unheard, the language becomes belligerent. Hearing rangatahi entails noticing what is unsaid, and understanding that physical gestures, lateness, and school avoidance, wearing a non-regulation jacket, playing manhunt, and non-participation in class are all forms of communication. These examples of “emergent listening” (Davies, 2016, as cited in Jones & Spector, 2017) draw us to consider rangatahi in the context of their whole lives and offer vital information as we consider how best to respond. AE teachers and tutors are conversant in this language, but it needs to be an essential everyday pedagogical posture for all professionals in education; to be able to listen in new ways forms the essence of an inquiring professional.

Secondly, Benjamin stated that school personnel should have considered, “how could we help him?” Themes that were derived from the analysis of 15 rangatahi stories provided us with the following recommendations for ways that teachers and schools can adapt to support disenfranchised rangatahi:

- The role of microaggressions and microaffirmations: Develop a culture of affirmation. Affirmation encompasses accepting each person for who they are and where they are in their education journey. This includes every day, continuous, prosocial interactions with rangatahi, and provision of space and physical places for rangatahi to express their identities and ethnic cultures.

- The role of the social and cultural in education spaces: The social and cultural contexts mediate all learning and need to be given equal attention in school planning as that of the academic curriculum. Approaches that strengthen community and social capital, and targeted programmes to eradicate bullying, will support vulnerable rangatahi. We found the use of withdrawal and time out spaces had detrimental impacts upon learning, wellbeing, and identity, and weakens social cohesion. Pedagogical approaches that utilise social learning models and reflect cultural identity will strengthen rangatahi engagement. The employment of suitably qualified personnel who work in the intersection of social and education spaces is a promising opportunity (Schoone, 2020a, 2020b).

- The role of pedagogy in rangatahi engagement. Having schoolwork that is at the correct instructional level, where rangatahi are scaffolded in their learning approach, will enhance achievement. In addition, a human/youth developmental perspective on learning is required. This entails teachers becoming conversant with trauma informed approaches, culturally responsive pedagogies, the teaching of specific skills for emotional regulation, and therapeutic support for rangatahi needing extra support due to trauma events, or ongoing trauma within and/or outside of school.

- The role of AE as restorative. The formal schooling system and AE should strengthen their connection with each other to share good practice and enhance support for transition of rangatahi between these settings (Bruce & Martin, 2023). Adopting a more porous model, where the flow of rangatahi and professional expertise between AE and schools is less arbitrary, could help normalise AE provision and facilitate a shared vision for the education of all rangatahi.

Conclusion

Just after the first COVID lockdowns in Auckland in 2020, when people were again permitted to meet faceto-face, a small group of academic researchers and AE co-ordinators met to discuss the idea of initiating a research project. As the group comprised those most familiar with the AE sector, accounting for many years of experience in managing, teaching, advocating, and researching in and for the ector, a long list of possible topics was soon generated. Charged with a further provocation of: “What would we most want to know now?” one AE co-ordinator remarked: “We want to know the stories. The stories of our young people.” The methodological question, of “how” these stories could be told became a major focus -that entailed the development of AE teachers as action researchers. Bringing forward their voices has been critical in the process of learning how to listen to rangatahi voices and gave us clues as to the potential of pedagogical transformation these stories inspire. Through the result of their inquiries, we have been gifted with models of inquiry and the education stories of 15 rangatahi. It is now our individual and collective responsibility to engage with this taonga, listen to rangatahi voices, and take action towards schooling transformation.

Footnotes

- In this report, the term “teacher” has been used as a catch-all phrase to include qualified teachers and tutors (see Schoone, 2016).↑

- Some rangatahi identify as both Pasifika and Māori. ↑

The research team

Academic researchers:

Dr Adrian Schoone is a Senior Lecturer in Education at AUT. He is an arts-based education researcher who focuses on AE, inclusion, and social pedagogy. Contact: adrian.schoone@aut.ac.nz

Dr Judy Bruce is a Research Associate at the University of Canterbury, and an Auckland-based education consultant. Her research crosses a range of justice contexts including global citizenship, service-learning, alternative education, youth development, and dis/engagement in education.

Eileen Piggot-Irvine is an Adjunct Professor of Leadership at Royal Roads University (Canada) and Griffith University (Brisbane). Amongst other things she has been Vice President of the international association Action Learning Action Research Association (ALARA), established the New Zealand Action Research Network, Director of the New Zealand Action Research and Review Centre (NZARRC), and Director of the New Zealand Principal Leadership Centre (NZPLC).

Dr Hana Turner-Adams (Ngāti Ranginui) is a Lecturer at the University of Auckland, experienced researching with Māori and non-Māori in educational settings, using both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies.

Research advisory members

Karyl Puklowski manages Auckland City Education School (ACES). Karyl is a founding member of the AE National Body, and the current Vice Chairperson.

Scott Samson was the former Director of the Waitakere Alternative Education Consortium. He is currently a Ministry of Education Senior Advisor.

Frank Veacock is the Director of the Waitakere Alternative Education Consortium.

Researchers with partners, left to right: Karyl Puklowski, Dr Adrian Schoone, Frank Veacock, Dr Judy Bruce, Scott Samson, Dr Hana Turner-Adams, Professor Eileen Piggot-Irvine

References

Research output publications

Fair, L., Gray, L., Fogarty, D., Meleisea, T., Bruce, J., Piggot-Irvine, E., Schoone, A., & Turner-Adams, H. (2023). Multiple, creative, methods for ‘giving voice’ in alternative education. Action Research Action Learning (ALARA) Monograph Series, 8. https://www. alarassociation.org/publications/alara-monograph-series/monographs

Schoone, A., Bruce, J., Piggot-Irvine, E., & Turer-Adams, H. (2022a). How alternative education teachers embarked on getting to the heart of young people’s schooling stories. International Journal of Inclusive Education. doi:10.1080/13603116.2022.2119289

Schoone, A., Bruce, J., Piggot-Irvine, E., & Turner-Adams, H. (2022b). Variations of I: Settling the poetic tone for student-voiced action research. Qualitative Inquiry, 29, 8–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800422113513

Schoone, A. (2023). Grand-theft auto/ethnography. In Voices unbound: Poems of the eighth international symposium on poetic inquiry (p. 164). African Sun Press.

Further references

Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educational Action Research 1(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010102

Barone, T., & Eisner, E. (2006). Arts-based educational research. In J. Green, G. Camilli, P. Elmore, A. Skukauskaite, & E. Grace (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 95–110). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Baroutsis, A., Comber, B., & Woods, A. (2017) Social geography, space, and place in education. In G. W. Noblit (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of education (pp. 1–16). Oxford University Press.

Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press.

Bourke, R., & Loveridge, J. (2018). Using student voice to challenge understandings of educational research, policy and practice. In R. Bourke & J. Loveridge (Eds.), Radical collegiality through student voice (pp. 1–16). Springer.

Brooking, K., Gardiner, B., & Calvert, S. (2009). Background of students in alternative education: Interviews with a selected 2008 cohort. New Zealand Council for Educational Research. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/backgroundstudents-alternative-education-interviews-selected-2008-cohort

Bruce, J. (2020). Alternative education workforce development in Aotearoa New Zealand: Lessons learned from related sectors. Report commissioned by Wayne Francis Charitable Trust and Vodafone New Zealand Foundations.

Bruce, J. (2021). Understanding the alternative education workforce in Aotearoa New Zealand. Report commissioned by Wayne Francis Charitable Trust and Vodafone New Zealand Foundations.

Bruce, J., & Martin, M. (2023). Combined activity centre/alternative education pilot, research project: Phase three report. Report commissioned by Ministry of Education.

Carpiano, R. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The ‘go-along’ interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place, 15(1), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003 Carr, W., & Kemmis. S. (2005). Staying critical. Educational Action Research, 13(3), 347–358. https://doi. org/10.1080/09650790500200296

Clark, T. C., Gontijo de Castro, T., Bullen, P., Fenaughty, J., Tiatia-Seath, J., Bavin, L., Peiris-John, R., Sutcliffe, K., Crengle, S., Lindsay-Latimer, C., Yao, E., & Fleming, T. (2023). Youth19 rangatahi smart survey: The health and wellbeing of young people in alternative education. The Youth19 Research Group, The University of Auckland and Victoria University of Wellington.

Cliffe-Tautari, T. (2020). Using pūrākau as a pedagogical strategy to explore Māori cultural identities. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (1), 12–18. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0156

Coghlan, D., & Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). Encyclopedia of action research (pp. 225–231). SAGE Publications. https://doi. org/10.4135/9781446294406.n97

Croghan, R., Griffin, C., Hunter, J., & Phoenix, A. (2008). Young people’s constructions of self: Notes on the use and analysis of the photo‐elicitation methods. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(4), 345–356. https://doi. org/10.1080/13645570701605707

Education Counts. (2021). Stand-downs, suspensions, exclusions and expulsions from school. Ministry of Education. https://www. educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/stand-downs,-suspensions,-exclusions-and-expulsions

Education Review Office. (2011). Alternative education: Schools and providers. https://ero.govt.nz/our-research/secondaryschools-and-alternative-education-april-2011

Education Review Office. (2023). An alternative education? Support for our most disengaged young people. https://ero.govt.nz/ourresearch/an-alternative-education-support-for-our-most-disengaged-young-people

Fa‘avae, D., Jones, A., & Manu‘atu, L. (2016). Talanoa‘i ‘a e talanoa—Talking about talanoa: Some dilemmas of a novice researcher. AlterNative, 12(2), 138–150.

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

Gruwell, E. (1999). The freedom writers diary: How a teacher and 150 teens used writing to change themselves and the world around them. Broadway Books.

Jones, S., & Spector, K. (2017). Becoming unstuck: Racism and misogyny as traumas diffused in the ordinary. Language Arts, 94(5), 305–312.

Kemmis, S. (2010). What is to be done? The place of action research. Educational Action Research 18(4), 417–427. https://doi.org/1 0.1080/09650792.2010.524745

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner (3rd ed.). Deakin University Press.

Niemi, R., Kumpulainen, K., & Lipponen, L. (2015). Pupils’ documentation enlightening teachers’ practical theory and pedagogical actions. Educational Action Research, 23(4), 599–614.

Piggot-Irvine, E., Ferkins, L., Rowe, W., & Sankaran, S. (2021). The evaluative study of action research: Rigorous findings on process and impact from around the world. Routledge Taylor and Francis.

Plows, V. (2017). Reworking or reaffirming practice? Perceptions of professional learning in alternative and flexible education settings. Teaching Education, 28(1), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1251416

Reimer, K., & Longmuir, F. (2021). Humanizing students as a micro-resistance practice in Australian alternative education settings. In J. K. Corkett, C. L. Cho, & A. Steele (Eds.), Global perspectives on microaggressions in schools (pp. 63–77). Taylor and Francis Group.

Schoone, A. (2016). The tutor: Transformational educators for 21st century learners. Dunmore Press.

Schoone, A. (2020a). Constellations of alternative education tutors: A poetic inquiry. Springer.

Schoone, A. (2020b). Imagining social pedagogy in/for New Zealand. International Journal of Social Pedagogy, 9(1), 2. https://doi. org/10.14324/111.444.ijsp.2020.v9.x.002

Smith, A. (2009). New Zealand families’ experience of having a teenager excluded from school. Pastoral Care in Education, 27, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643940902897665

Sue, D. (2018). Microagressions, marginality, and oppression. In M. Adams, W. Blumenfeld. C. Castenada, H. Hackman, M. Peters, & X. Zuniga (Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (4th ed., pp. 22–26). Routledge.

Sutherland, A. (2016). The relationship between the compulsory school experience and youth offending. In P. Towl & S. Hemphill (Eds.), Locked out: Understanding and tackling school exclusion in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 114–134). NZCER Press.

Thomson, P. (2007). Working the in/visible geographies of school exclusion. In K. Gulson & C. Symes (Eds.), Spatial theories of education: Policy and geography matters (pp. 111–120). Routledge.

Thomson, R., Bell, R., Holland, J., Henderson, S., McGrellis, S., & Sharp, S. (2002). Critical moments: Choice, chance and opportunity in young people’s narratives of transition. Sociology, 36(2), 335-354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038502036002006

Tomorrow’s Schools Independent Taskforce. (2019). Supporting all schools to succeed: Reform of the Tomorrow’s Schools system.

Ministry of Education. https://conversation.education.govt.nz/conversations/tomorrows-schools-review/

Vaioleti, T. M. (2006). Talanoa research methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education, 12, 21–34.

Webber, M. (2012). Identity matters: Racial–ethnic identity and Māori students. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (2), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0370

Webber, M., & Macfarlane, A. (2020). Mana tangata: The five optimal cultural conditions for Māori student success. Journal of American Indian Education, 59(1), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaie.2020.a798554

Woodcock, C. (2016). The listening guide: A how-to approach on ways to promote educational democracy. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406916677594

The appendices for this online version of the report have been removed. However, you can access them here