Introduction

Ma’au i lou ofaga, maua’a i lou faasinomaga.

Keep your identity alive to thrive.

This 2-year collaborative research project focused on young children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture, how early childhood teachers can nurture and encourage this learning, and how this in turn impacts on children’s participation in early childhood education (ECE) communities. The project builds on a previous Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) project that explored children’s working theories in action in five Playcentres in Canterbury (Davis & Peters, 2011). That project showed ways children express and develop working theories, how practitioners understand these, and how best to respond to this learning (Davis & Peters, 2011). While there has been considerable local and international interest in the findings of that project, one of the limitations of the work was that children’s diverse cultural knowledges, ideas, and actions were not investigated. This project sought to address these limitations by contributing to what is known about how teachers can help children to make sense of their ‘cultural self’ and the social world, and of difference and similarities, issues that are frequently silenced in young children and in learning communities (Brooker & Woodhead, 2008; Copenhaver-Johnson, 2006). The project explored ways teachers can support diversity, and participation, through pedagogy and programme design that is highly responsive to all learners. This is especially desirable for the potential influence on the practice and understandings of those working with young Pasifika learners—an area where there has been very little research undertaken in Aotearoa New Zealand to date.

Working theories are defined in the revised early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki as:

… the evolving ideas and understandings that children develop as they use their existing knowledge to try to make sense of new experiences. (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 23)

A Samoan interpretation of the concept is “O se ‘faugamanatu e tau saili’ili ai le tapenaga o le moe ma le utaga o manatu.” This interpretation reflects the gathering of thoughts and ideas to make meaning, to search for understanding, and to express what we know and don’t know. Working theories develop through experience with people, places, and things over time, and are closely linked to learning dispositions. For many, their working theories are also closely connected to their spirituality (Ministry of Education, 1996). Children generating and refining their working theories is described as an important learning outcome in Te Whāriki because working theories (and learning dispositions) “… enable learning across the whole curriculum” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 23).

May Crichton, one of the teacher–researchers from Mapusaga A’oga Amata, provided the Pasifika analogy of “O le popo ma lana malaga fa’amisiona (the way a coconut goes on a mission)” to explain the ways working theories emerge, develop, or appear to be fleeting comments. In the islands a lot of coconut trees grow by the sea. Once the coconut matures it often falls in the ocean and then it can begin its travels. The sea current can take the coconut in many different directions. Some might wash back to land and many float in the ocean. The coconuts that are washed back to land will grow and produce more coconut trees, but some never find land and may not produce new trees, just as a child’s idea or wondering may surface but appear not to develop beyond that moment.

Both the Pasifika Education Plan (Ministry of Education, 2008b, 2013b) and Ka Hikitia (Ministry of Education, 2008a; 2012) place importance on the ways teachers support and respond to children’s identity, language, and culture, through culturally responsive pedagogy and developing their own cultural intelligence. The Pasifika Education Plan (Ministry of Education, 2013b) seeks to ensure that Pasifika learners are “secure and confident in their identities, languages and cultures” (p. 2). This security and confidence is in turn connected to belonging. The link between belonging and learning is an important one, because through belonging comes participation, and through participation comes learning (Rogoff, 2003). By taking careful notice of the working theories children are expressing about their identity, language, and culture, teachers will be more informed about whether their attempts to support and nurture the child’s identity, language, and culture are working, or not.

The research questions

The project sought to address four overarching research questions:

- What are young children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture and how do they express these?

- In what ways can teachers support and encourage the development of children’s working theories about their own identity, language, and culture?

- In what ways can teachers support and encourage the development of children’s working theories about the identity, language, and culture of others?

- How does nurturing and encouraging children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture impact on children’s participation in the early childhood education communities?

Research design

Taking a ‘sister centre’ approach

The project was based in two community ECE centres in Christchurch: Mapusaga A’oga Amata and North Beach Community Preschool. The communities of the two research centres have experienced significant damage and hardship since the 2010/11 Canterbury earthquakes. The research partnership was born out of professional development support and projects following the earthquakes, and builds on the community spirit that emerged through these experiences.

The two research sites acted as ‘sister’ centres; both collaborating and supporting one another throughout the project. The sister centres contrast in that Mapusaga A’oga Amata is a full Samoan-immersion environment while North Beach Community Preschool is English-medium. North Beach Community Preschool has teachers and families from diverse cultures and the dominant culture is Pākehā or Palagi. As a Samoan-immersion setting, the language and culture of Mapusaga is deeply rooted to Samoan ways of being, knowing, and doing. Many of the families at the two centres are first or second generation New Zealanders.

The concept of the ‘sister’ relationship used in the project is based on a concept derived from Samoan culture. In the Samoan world there is a saying, “O le i’oimata o le tuagane lona tuafafine”—The sister is the pupil of her brother’s eye. This saying signifies the sibling covenant: a reciprocal and sacred obligation to one another’s wellbeing. The root word in feagaiga (covenant) is feagai which means to be opposite each other within the same space, but not in opposition. The concept of sisterhood is based on mutual respect (va fealoaloa’i). When used in the context of human relationships, as in the case of our research, ‘va’ refers to a relational space, one that includes physical, spiritual, and historical dimensions. This sister relationship offers a valuable contribution to research because such a partnership has the potential to ‘unlock’ what Tuafuti (2010) called the “Pasifika culture of silence in educational contexts”. Tuafuti suggests this can deepen exploration “… of the discourses between the dominant education system and Pasifika communities” (p. 4).

The ‘sister’ relationship extended to encompass the research leaders and support team from CORE Education— Keryn Davis (researcher), Ruta McKenzie (researcher), Dalene Mactier (research assistant), and the University of Waikato research associates, Dr Sally Peters and Vanessa Paki.

The two centres

North Beach Community Preschool is a not-for-profit centre that has been operating in the community since

1998. Following the Canterbury earthquakes of 2011 and 2012 the centre relocated onto the grounds of Rawhiti School. The centre is licensed for 32 2-to-5-year-olds, and eight under 2-year-olds. When the project first started in 2015, many of the children who attended the centre were from families with low incomes, and many have complex social needs. The centre had a growing multicultural community with an influx of families arriving from around the country and the world to help with the rebuild. As the project progressed, the community settled and the demographic shifted to serve more middle-income families.

Mapusaga A’oga Amata is a church owned and governed Samoan language early childhood centre. Mapusaga A’oga Amata operates in the grounds of the Samoan Congregational Christian Church. The centre is licensed for 29 children. Most children who attend the centre are Samoan. Parents, staff, and church leaders are represented on the management committee of the centre. The centre was established to promote the Samoan language and to provide early childhood education within Samoan ways of being.

Mapusaga A’oga Amata and North Beach Community Preschool have five and 10 teachers respectively. All of the teachers participated at some stage in the project as teacher researchers; however, at different stages and as focuses shifted, some were more involved than others. Each centre nominated a lead teacher researcher who oversaw the work in their centres.

Extended Community of Inquiry

E le sua le lolo i se popo e tasi. Aoao manogi o le lolo e faasoa ai manatu.

The making of oil needs more than one coconut.

The Samoan proverb above reflects the way that this project relied on the gathering of many different voices to contribute to the thinking. A further special feature of this project was the establishment of an Extended Community of Inquiry around the project team. The team’s vision for this was to reach out to people outside of the immediate project team to ‘surround’ the project team with perspectives and viewpoints so as to contribute to the thinking that developed during the project. The people in this group brought specialist expertise; for instance, in the form of cultural and pedagogical expertise, a range of early childhood and primary education experience, as well as thought leadership. In turn, this wider learning community was able to access the ideas that emerged from the project as they developed, thus reducing the lag to these ideas permeating into the sector and beyond. In this way the model sought to promote maximum uptake and dissemination of a pedagogical model that is grounded in community and cultural responsiveness. While the project team would have liked more opportunities to connect with this network of support, the model had significant impact in terms of inspiring others and speeding up change as the project progressed.

Data gathering and analysis

This study was guided by interpretivist theoretical perspectives and the team employed methods aimed to explore the participants’ views and their experiences of the world (Taylor & Bogdan, 1998). The project team applied an action research approach to the study and involved cyclic ‘drilling down’ to explore the topic in increasingly greater depth. This approach was employed because it allowed the team to collaborate in a process of problem posing, data gathering, analysis, and action around teaching and learning (Cochran-Smith & Donnell, 2006). The approach was designed to meet Kemmis and McTaggart’s (2000) criterion of useful action research, in which participants develop a stronger and more authentic sense of understanding and development in their practices, and the situations in which they practice.

A range of data collection methods was used to capture children’s expressions and responses to experiences, and to delve into teachers’ perspectives, understandings, and practices in relation to the project focus. Data collection and analysis revolved around four phases. Each phase was an action research cycle and therefore each had its own cycle of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. Case studies of eight children were also employed as one of the methods within these cycles. Smaller cycles also developed in Phase Three as teacherled inquiries, referred to as mini-projects (Peters, Paki, & Davis, 2015).

A method of particular importance in this project was the use of talanoa for data collection. Talanoa, as an approach, is a well-known and familiar model for Pasifika peoples. ‘Tala’ means to talk, inform, and tell. ‘noa’ means any kind of void, ordinary, continuously, or never ending. It is the sum of tala and noa that supported the participants, and the project team, to partake deeply in this experience. Talanoa refers to having a conversation, a talk, or an exchange of ideas in an informal or formal way. The significance and value of talanoa for both participants and the research team was that it enabled those involved to ‘talk from the heart’, a process that involves storytelling and making connections with stories. Embedding the method of talanoa within this project enabled stories to be shared and told in a non-threatening manner through respect in the face-to-face manner between the researchers, teachers, children, and parents. Through the talanoa process itself, trust was formed and embraced by both the participants and the project team. This relationship of trust was based on the principles of honesty, inclusion, sincerity, respect for each other, and respect for spirituality.

Data sources included:

- centre documentation—for example, documented child assessments (i.e., content of children’s portfolios, Learning Stories) and programme planning

- photographs

- videos

- talanoa, discussions, and interviews—for example, recorded parent and teacher interviews, research team meetings, conversations with children

- children’s work—for example, drawings and other things they have made or created

- teacher and researcher notes and reflections

- observations (both formal and informal)

- comments and reflections of members of the Extended Community of Inquiry.

A discussion of data gathering and analysis undertaken in each phase follows.

Phase One

Phase One revolved around the goals of firmly grounding the research focus across both sites; establishing a clear focus on working theories relating to identity, language, and culture in the centres; and teachers beginning to identify and gather examples of the ways children express their theories in action. Ethical approval was sought from CORE Education’s Ethics Committee and consent obtained in the following weeks from the teachers and families. The researchers made several site visits over this phase. These visits were four-fold in purpose:

- To support the consent process by being available to teachers and families to discuss the project and any questions they may have about their involvement.

- To support the teachers to identify and document examples of the ways children are expressing their working theories about identity, language, and culture in the centres.

- To identify case study children (four from each centre).

- To establish the initial ‘story’ of each of the four case study children in each setting.

The eight case study children selected were no older than 3 years, 6 months of age at January 2015 (to account for school movement) and were representative of the average attendance of children of a similar age at each centre. Data collection for case studies began in March 2015 and continued until the project ended in December 2016, or until the children started school or left the centre.

Initial case study data included:

- observations using the Leuven Involvement and Well Being Scale (Laevers, 1994) to provide insights into the nature of children’s engagement and emotional responses as they participated in the centre programmes

- collecting, collating, and analysing existing data on the children (i.e., assessment documentation from their portfolios)

- interviewing teacher researchers about their perceptions of the child’s participation in the programme, the child’s identity, language, and culture, and their observations of the child’s expressions of their working theories about identity, language, and culture

- interviewing parents and aiga about their perceptions of the child’s participation in the programme, about the child’s identity, language, and culture, and their observations of the child’s expressions of their working theories about identity, language, and culture

- talking with the child about their participation in the programme (i.e., their likes, dislikes) and about elements of their identity, language, and culture and that of others, using drawings (i.e., by inviting them to draw a picture of themselves, others, what they like doing at centre etc., and talking about their drawings with them).

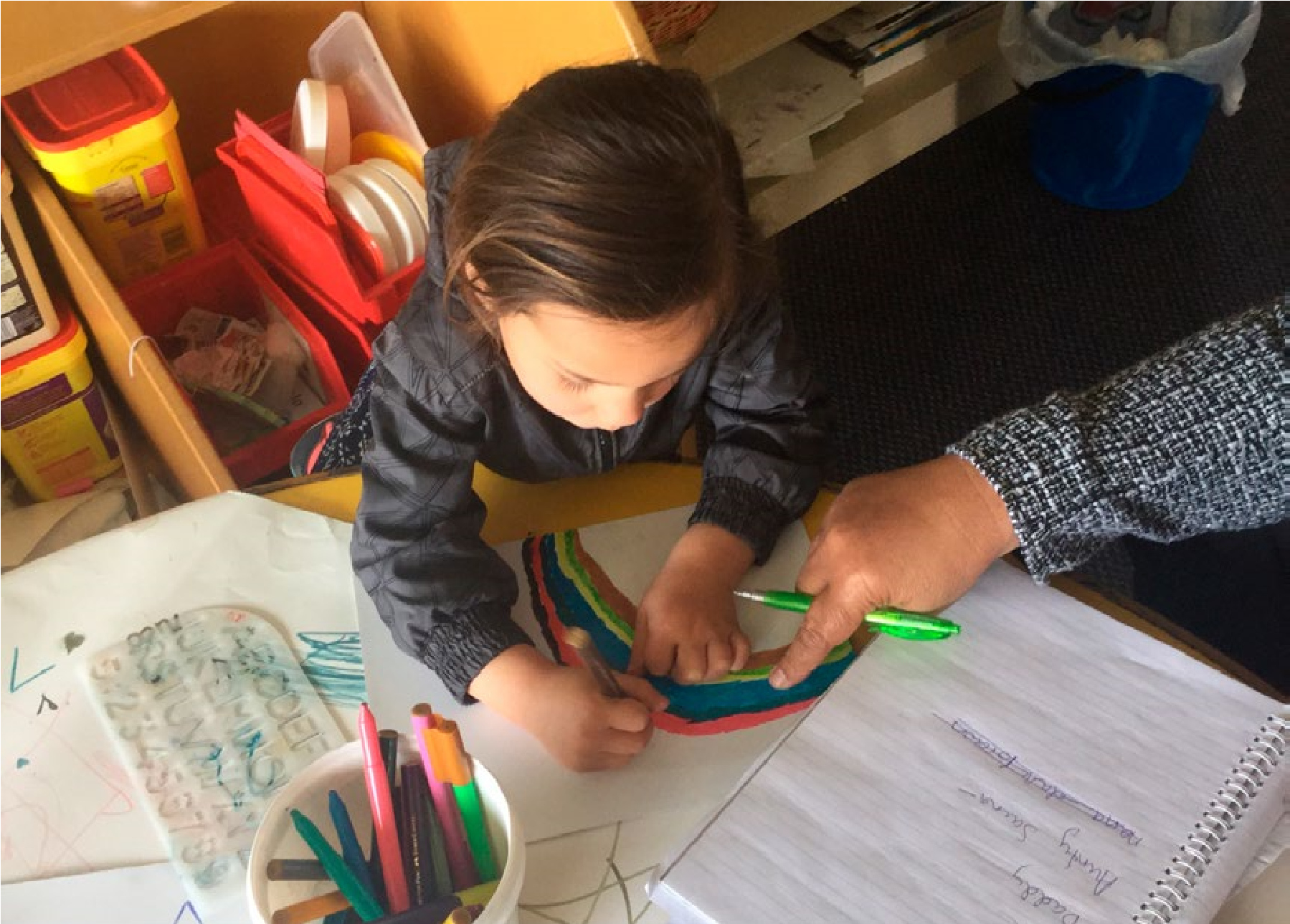

Figure 1: A case study child’s drawing that includes her friend who is Māori. She explains, smiling widely, “He says ‘kia ora’. That means ‘good morning’.”

Phase Two

The researchers undertook an initial analysis of the case study data over the early stages of Phase Two in preparation for deepening understandings and explorations using the data. The initial ‘story’ for each case study child was shared back to the teachers at various points across this phase. Teachers continued to document examples of what they were noticing about children’s working theory behaviours as described in Phase One, with a focus on gathering this data on case study children.

At team meetings, and during site visits with researchers across this phase, the teachers shared examples of what they had noticed about children’s working theories and with the researchers. The emphasis at meetings and site visits was to create opportunities for critical inquiry: to question the ‘unquestioned’ and delve deeply into the meanings and assumptions of ideas and examples offered. The examples shared were analysed together and brief summaries constructed about possible theories being expressed by children, the associated learning outcomes, and identified teacher pedagogy that contributed to these outcomes (or not). The findings generated from this process were a catalyst to teachers identifying, designing, and undertaking mini-projects on specific adaptations to their teaching strategies, the programme, or to kick start innovations and new use of resources.

Phase Three

The third phase of the project revolved largely around the ongoing collection of data in relation to case study children, and the identification, implementation, data collection, and analysis of mini-projects. The researchers supported teachers in planning and undertaking their inquiries during regular visits to the research sites, providing mentoring and coaching, and literature to strengthen their inquiries. Like previous phases, these site visits (and team meetings held across this phase), were important times for collating, discussing, analysing, and for identifying next steps.

Team meetings included sharing stories and examples, talanoa, presenting back findings, generating and refining new questions, identifying and overcoming possible dilemmas or issues, and next steps in the research process. The initial data gathering and analysis process described in phase one was also repeated during this phase for case study children.

Phase Four

The final fourth phase provided the opportunity for the team to work more closely with the data sets to identify and discuss emerging themes, identify any gaps in data, and undertake a detailed analysis. At this point, further data were gathered in relation to a final emerging mini-project that included some of the case study children who had transitioned to school.

Findings

The discussion that follows provides an overview of some of the key findings drawn from the general data set, mini-projects, and case studies.

Children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture

Rather than being just carried around in the heads of learners, learning and knowledge (some of which can be understood as working theories) can be understood as being ‘situated’: “… in terms of a relationship between an individual with both a mind and a body and an environment in which the individual thinks, feels and interacts” (Gee, 2008, p. 81, emphasis in original). Across each phase of the project, the research team searched for examples of how this relationship plays out through the observable actions and behaviours of children as they participated in day-to-day centre life.

By capturing and analysing children’s expressions, actions, and interactions teachers and researchers noticed, the project team was able to reveal some of the theories the children may be developing. While it is not possible to be certain of these theories, it is possible to theorise about what these actions and behaviours represent in terms of the child’s ideas and understandings and those the child may be applying as they try to make sense of new experiences. The project team found that when teachers strived to understand children’s learning in this way, they felt they were in a stronger position to design more focused and worthwhile teaching responses (Drummond, 1993), even if what they planned didn’t always work out right the first time.

Four types of working theories

From the team’s analysis of the data collected, four broad overlapping types or categories of children’s working theories emerged:

- making sense of cultural values and practices

- making sense of connections • making sense of their cultural selves

- making sense of others.

An explanation of each of the four types of working theories, with examples, is provided in the table that follows.

| 1. Making sense of cultural values and practices | |

| Description | Examples |

| Language, behaviours, or actions that reflect the child’s growing understanding or appreciation of cultural values and practices of this place. | Children at North Beach Community Preschool independently fetching their lunch boxes, finding a place to eat, and together reciting karakia mō te kai before eating. Children at Mapusaga A’oga Amata taking singing ‘seriously’ and singing with ‘heart and soul’. A child making meaning of Western weddings by testing out what it is like to spend a day wearing high-heeled shoes. |

| 2. Making sense of connections | |

| Description | Examples |

| Language, behaviours, or actions that reflect the ways the child is making connections between worlds, and with and between people, and how they are making sense of these connections. | Extended discussions of Samoa as a place, and the defining features of this place. For example, whenever a plane flies over the centre one child announces, “O le va’alele la le e alu i Savai’i (that plane is going to Savai’i).” When she saw a boat in a video she said, “O le va’a la le e alu i Savai’i (that is the boat that goes to Savai’i).” A child demonstrating a sense of responsibility for a younger child (who had difficulty at times joining play with others), by choosing to play with the child, declaring to a teacher that the child was ‘actually quite nice’ and would be a ‘good friend’ for her little brother who was about to start at the centre. A child creating visual representations of her extended family, using symbols such as shapes or lines of different sizes and lengths to represent the family order. |

| 3. Making sense of their cultural selves | |

| Description | Examples |

| Language, behaviours, or actions that reflect the ways the child is asserting or expressing ideas and understandings of, or identifying with, their own identity, language, and culture. | A child whose family hunts and camps, incorporates many aspects of this culture into his play at the centre. Children participating in cultural celebrations (such as White Sunday, by learning songs, dances, and Bible verses), and when children participate in centre rituals such as lotu (prayer) time. A child who has dual heritage and two names (a Samoan name and a Palagi name) corrects her Samoan teachers when they use her Palagi name, telling them to call her by her Samoan name as this was given to her by her Samoan grandmother. A child who demonstrates the Christian values of her family without prompting by encouraging other children around her, such as when the child looked over at the younger child’s drawing and said, “ That’s a cool picture [child’s name]” then approached Debs (a teacher) and said, “Debs it’s cool, but not that cool, I’m just encouraging him.” |

| 4. Making sense of others | |

| Description | Examples |

| Language, behaviours, or actions that reflect the ways the child is expressing ideas and understandings of, or identifying with, the identity, language, and culture of others. | A child who can speak Samoan and English well has worked out who can speak these languages well too. She chooses which language to use depending on who she is speaking to. This child also takes responsibility for her brothers by instructing them to speak Samoan when she hears them speaking in English. A child was invited to draw a picture of one of her teachers. The teacher is Māori. The child proceeded to draw this teacher alongside another teacher (Nora, who is Filipino), saying “Nora and you are the same.” When Ruta (Samoan researcher) was in the centre alongside a visiting Samoan family, a child asked, “Why are all Nora’s family here?” |

Supporting and encouraging children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture: Mini-projects

Mini-projects were a major focus across Phase Three of the project. In acknowledging Pasifika practices, these small inquiries were teacher-led and undertaken in pairs or groups as well as by individuals. Who was involved and levels of involvement were determined by the teachers themselves. Each mini-project explored a construct, and reflected the teacher’s personal interests or challenges, the research questions, and some developed across the two sister centres. These projects also built on work undertaken in earlier phases, but there was flexibility in terms of scope, scale, and lifetimes of these projects. Some mini-projects ran for only a few weeks, others up to several months, while another ran for more than a year. As this work developed it became clear that while this work explored outcomes for learners, the work undertaken brought about tangible shifts in the heads and hearts of the teachers too.

A total of 10 mini-projects were undertaken by the teachers. Some of these projects overlap and also connect to case studies of individual children:

- building cross-cultural connections (field trips to the two centres)

- lifting the tapu (shifting the balance of power towards children at lotu time)

- growing islands of interest to build identities (extending children’s thinking about self and others through superheroes)

- expressing ideas and understanding of identity, language, and culture (enhancing socio-dramatic play to support meaning making)

- encouraging problem solving and critical thinking (teachers developing habits of practice)

- sharing of resources (the exchange of resources between the two centres)

- seeing unspoken working theories about identity, language, and culture (an exploration of the working theories North Beach Community Preschool’s youngest learners)

- strengthening the sister relationship (teachers’ intentional steps for cross-cultural understanding)

- continuity in identity, language, and culture (supporting children’s transitions to school)

- understanding Pākehā/Palagi culture (exploring what Pākehā/Palagi culture is).

Explanations and findings from three of these mini-projects follow.

Building cross-cultural connections

This mini-project revolved around an interest in learning outcomes for children when teachers intentionally took steps to grow connections and relationships between the Mapusaga A’oga Amata children and North Beach Community Preschool children. Across 14 months of the project the teachers and children visited each other’s centre on five occasions.

During each trip the hosting centre shared aspects of their culture, through routines and rituals and play experiences. Features of these trips included group mat times, singing, lotu, opening of coconuts, sharing and eating different foods, free play (including dramatic play, games, construction, sandpit play, etc.), storytelling, shared books, and visiting the Samoan Congregational Christian Church on the grounds of which Mapusaga is located. When North Beach Community Preschool visited Mapusaga A’oga Amata, the Mapusaga teachers provided a full Samoan-immersion experience for the North Beach children. Two visits to Mapusaga A’oga Amata coincided with Samoan Language Week. One visit included two of the case study children from North Beach sending the Mapusaga children a video invitation to visit North Beach that featured different aspects of their centre. The Mapusaga children, with the support of their teachers, were able to identify some features that were different from what they had at their centre, prompting them to plan what they wanted to get out of the trip.

Figure 2: North Beach children watch aiga prepare an umu during a trip to Mapusaga.

Reflection on the visit, and analysis of the data collected before, during, and after these visits helped surface many differences between the two centres, both for children and adults. By surfacing these features together, children and teachers were able to make sense of these differences, find connections, and navigate their experiences of these differences. By maintaining a close focus on children’s responses to the differences and similarities noticed by the children, and through revisiting videos of these trips together, teachers were able to monitor the learning outcomes for children as these were recognised. They were able to plan their interactions, conversations, and the environment to be responsive to what they were noticing. For example, when one child was noticeably shy on a visit to the other centre, the teachers were able to talk with him later about the experience, help him to discuss and make sense of his feelings. They were able to involve him more in future related experiences, and be more proactive in their use of language with him before, during, and after the next visit. Munira, a teacher, reflects:

He was not very sure of his surrounding environment and decided to stay close to Chris. He was shy. He was uncertain. He had no idea about what to expect. I think we can relate to this scenario as adults. What do we do when we enter into a completely unknown territory? How do we calm our nerves and try to make ourselves comfortable? I can relate to this … But being prepared has helped, I think. How can we prepare our children to venture into the unknown with confidence?

By the end of the project, the team had detailed data that captured children becoming more comfortable and interested in being with and part of this combined community of learners. The data showed how this collaboration was impacting positively on their views and responses to both children and adults who use languages different from their own, or have different skin colour to them, but also in terms of their engagement in cultural practices such as dance, singing, food sharing, and in play. As Munira, explains:

The mini-project of planning visits between the sister centres was an ideal platform for us to understand the Samoan culture and provide rich opportunities for children to make connections with their Mapusaga friends.

Through watching our case study children during these trips, we were able to see how children can evolve, learn to understand, respect and celebrate the differences in identity, language and culture around them through exposures to these rich cultural experiences.

Lifting the tapu

E sui faiga, ae tumau lava fa’avae.

Methods can change, but foundations remain.

This mini-project was undertaken at Mapusaga A’oga Amata. It emerged out of the Mapusaga teachers’ analysis of observation data collected on case study children using the Leuven Involvement and Well Being Scales. These scales are an interval-based observation tool designed to focus on the nature of children’s engagement (Involvement) and emotions (Well Being) while the child is participating in an educational setting (Davis, 2015). Using this tool provided a different view of the case study children’s participation during lotu time.

The lotu, or prayer time, is an important cultural routine and ritual of the centre and the life of church, family, and community celebrations. The teacher’s goals for children at lotu time revolve around the children’s development of spiritual and language competencies that are deeply representative of what it is to be a

Christian Samoan in their community. While the data from observations using the Leuven Involvement and Well Being Scales only provided a snapshot in time, the data generated from observations over time of the case study children allowed the teacher to see the nature of the children’s participation in a way they hadn’t seen it before. The data generated from these observations surprised them, in that the data showed the case study children’s involvement levels were lower at lotu time than any other time. The teachers were moved to reflect on what they might try in order to shift the children’s involvement to better meet their goals for the children. They wanted to explore ways to create opportunities for children to contribute more to lotu time:

I thought I was doing a great job at lotu time, but I was so surprised to see the result when I saw the data. … Teachers always lead lotu time. I want to make a change. I want children to lead the lotu time. (Fa’amavaega, teacher)

The teachers felt challenged by the tension between their deep desire to uphold their cultural traditions while also responding to the observation data and project focus:

The discussion around lotu was very challenging. There is a contradiction between the culture and lotu when we think about children’s working theories. When it comes to lotu, all children must participate because it’s the way we have been brought up and it’s part of the culture. In the child’s own working theory some children might think, ‘I don’t want lotu time.’ These are the challenges that we are facing today, but we as teachers we need to be resourceful and find ways that respect and acknowledge both. (May, teacher)

The teachers decided to make some small but significant changes to lotu time. These changes included children being offered the responsibility to lead lotu time and determine what ritual would be included, and how it would be conducted. The teacher started to invite a child to lead this time. They used questions and statements to stretch children’s thinking and encourage shared discussion. They provided encouragement and were mindful of the tone of their voices. Very soon the teachers started to recognise the positive outcomes for the children from these changes:

I see new learning in children taking leadership and ownership for their own learning. I invited Talia the very next morning to see if she could lead the lotu. That was the day I saw a different Talia. She was very happy. … Malachai [a case study child] is also different in the way that he leads lotu time. He is very confident and not shy any more. (Fa’amavaega, teacher)

While the teachers began to recognise the value of the changes they had made for children, it emerged later that there was some unease for some members of the team around the children taking on the roles traditionally held by adults in the Samoan culture. While the teachers recognised the value for the children, and were proud of the cultural competencies the children displayed, they were reserved about sharing this practice outside of their centre. The words of Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Ta’isi (Head of State of Samoa) in his keynote address to the Epiphany Pacific Trust in Auckland on 10 July 2016 were helpful and empowering to the team to see their teaching practices can evolve to have a positive impact on learning, without undermining their culture:

Knowledge is power but it also core to our tu ma aga (our customary values and practices), our faasinomaga (our true identities as Samoans), our aganuu and agaifanau (our custom laws and values). … we need to lift the tapu over certain aspects of our indigenous knowledges so that they can survive and flower, so that our children and their children and their children’s children can know them and love them as we do.

Encouraging problem solving and critical thinking

The mini-projects have allowed teachers to play with strategies for prompting and encouraging children’s thinking using the cross-cultural experience of visits by children and teachers to each other’s centre. One of the goals of these visits has been to see what children ‘pick up’ from each centre in the hope of growing new or mutually interesting ideas between the children of the two centres. Video footage of children and teachers in action before, during, and after these trips was collected so that later members of the project team could revisit this footage to revisit children’s words and actions more carefully than is possible when learning and teaching is ‘in flight’.

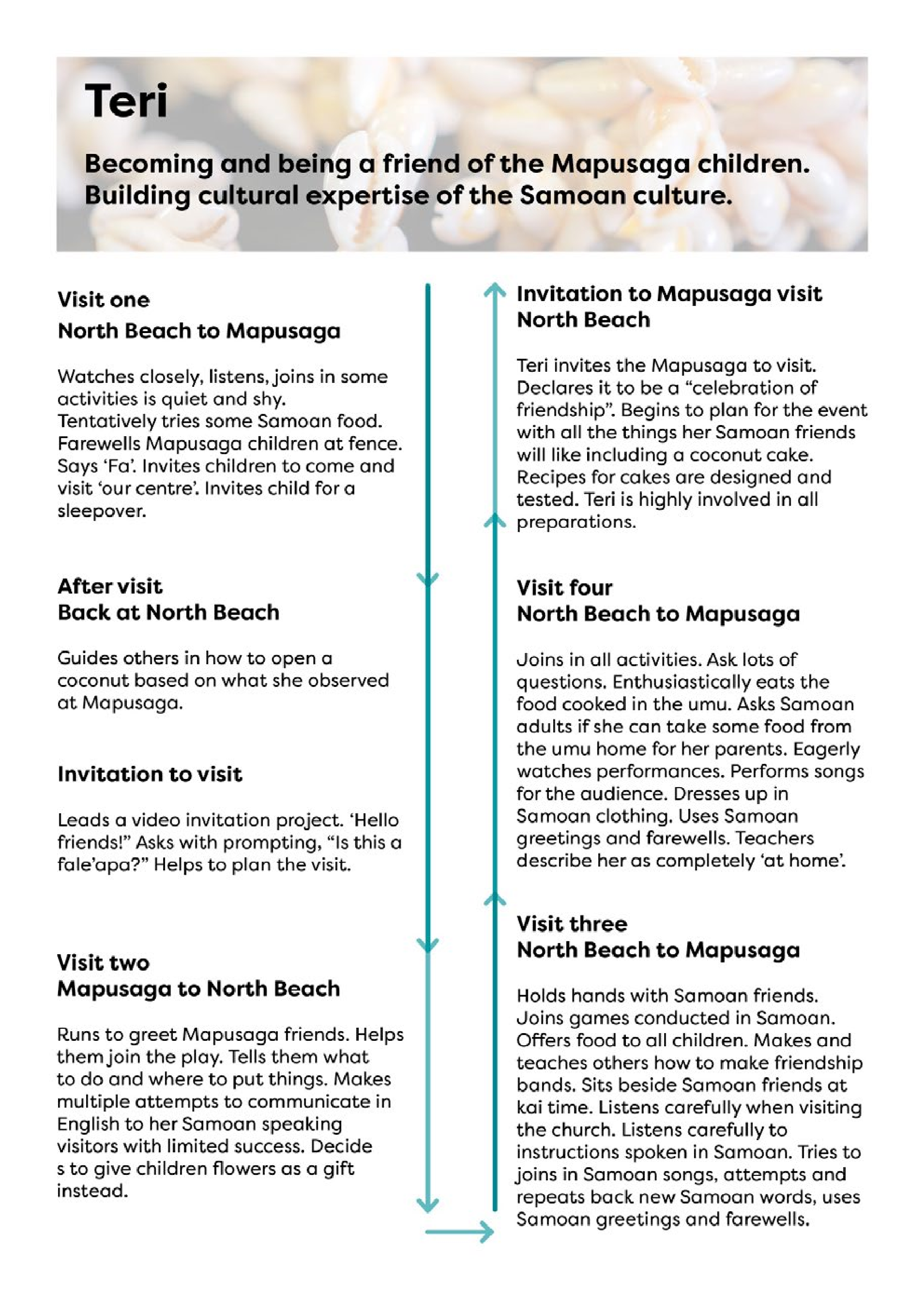

This video footage also proved to be a powerful tool in assisting the team to analyse teachers’ strategies and responses. Hannah and Hayley are two teacher researchers who have made good use of what they saw of their practice from video footage of children and teachers after returning from their first visit to Mapusaga. At this visit, Mara (a Mapusaga teacher) had demonstrated how to open a coconut with a machete and later the North Beach children were given a coconut to take back to their centre. On their return, it was decided to open the coconut and Hannah and Hayley had worked hard to listen to and follow the children’s theories about how to do this. These theories included children’s conflicting ideas about the best way to open a coconut: one being by placing it on a chopping board and sawing it with a knife, the other by doing like Mara had, by holding it in one hand and hitting it on an angle with a knife. Eventually the coconut was opened, using Mara’s approach, but this interaction was challenging for the teachers and they commented that they ‘ran out’ of in-the-moment responses to support this intense shared thinking episode.

Figure 3: Angus demonstrates his theory about how to open coconuts.

After carefully watching this footage together with Keryn (researcher), Hannah and Hayley recognised the need to broaden their repertoire of strategies to better foster children’s working theories, which included talking less and listening more. They were determined to develop some these new habits of practice; however, these new strategies took time to become natural to them, and initially the teachers felt awkward:

| Hannah: | I’ve really been aware of how much I talk. And … how many questions I ask. But instead of questioning I get a wee bit stuck on what to say, and I feel like I say the same thing quite a bit. So, I think just playing around with … just different ways of wording things … and I guess the more that we do it, the easier it will become. But it feels a lot like it’s ‘Oh, I wonder …’ Hmm. |

| Hayley: | We feel quite dorky. We were almost laughing at each other the other day. |

| Hannah: | Hannah: It doesn’t flow very naturally at the moment. |

While they may have felt “dorky”, Hannah and Hayley could see a difference for children’s learning the very first time they intentionally chose to use these strategies around an authentic opportunity for problem solving:

| Hannah: | But even though it was a bit awkward at times what we got from that situation was so much more, there was so much richness. |

| Hayley: | It’s totally different to what we would have done a day earlier! |

Working theories and participation in the ECE communities: Case studies

The opportunity to track children in each centre for almost 18 months provided a rare insight into the influence their ECE experience can have on their working theories about identity, language, and culture. Of course, these ECE centre experiences are only part of the story. The sum total of each child’s lived experiences, families, extended network of relationships, and their own language, culture, and identity are tremendously powerful influences on how a child develops and applies their existing knowledge to try to make sense of new experiences.

In this project, the case study data were used to create a type of ‘mirror’ for which to reflect on children’s experiences and theories, as well as teacher pedagogy. These data were used by the research team to make visible to them the ways identity, language, and culture of the child influences the child’s learning and participation in their early childhood centre community over time, as well as the ways they and others saw, supported, and nurtured this, or didn’t.

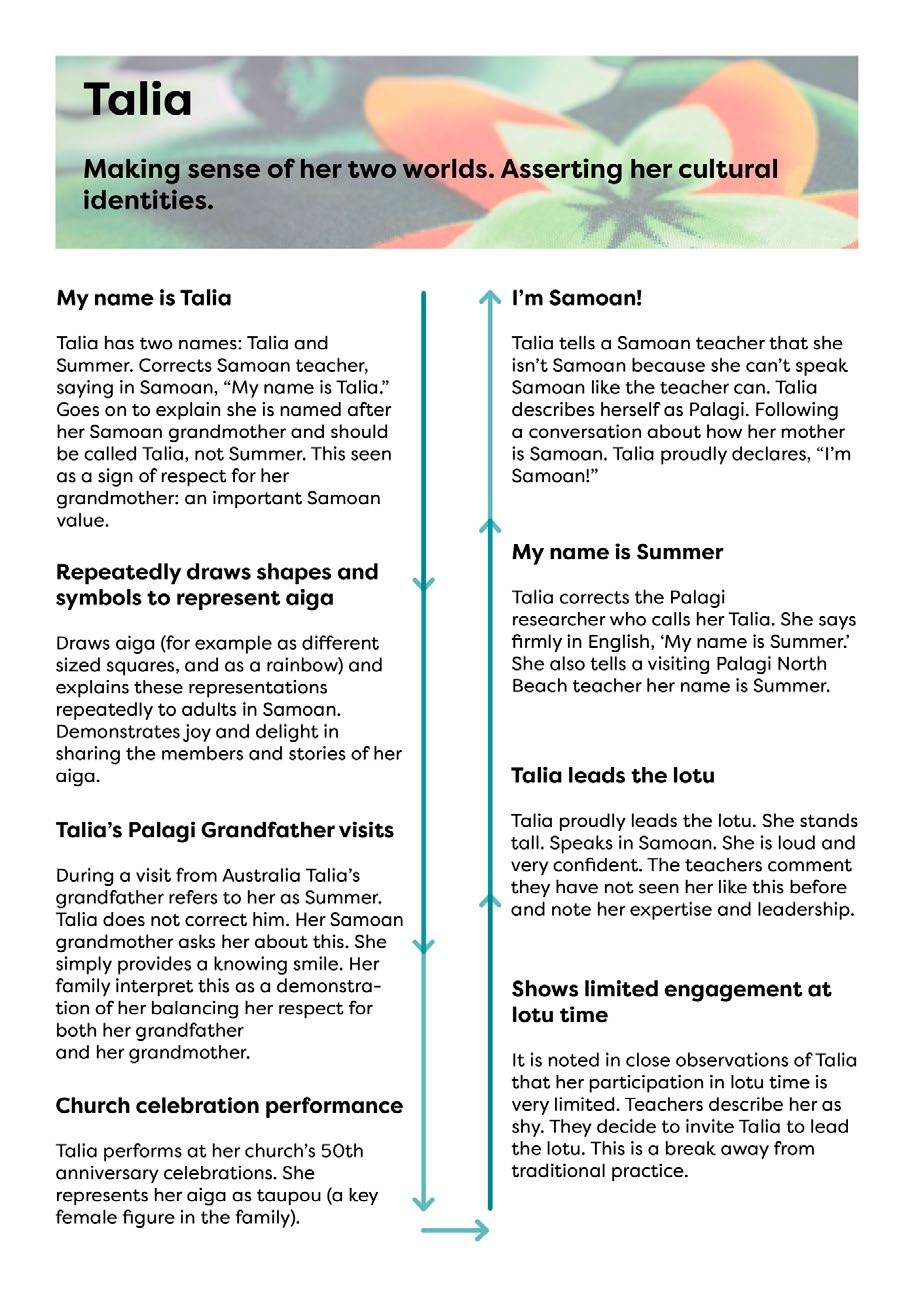

Figure 4 : Talia, a case study child, represents her aiga as a rainbow.

Some of the case study data collection took place outside of the centres; for example, Ruta (researcher) observed two of the Mapusaga case study children at White Sunday and at other special church services. At these events the case study children recited Bible verses, participated in action songs, and took part in the choir. Participating in these important cultural events was interpreted by the Samoan members of the project team as a demonstration of ‘taking responsibility’ and leadership in action. Data collection outside of the centre reflects the connected nature of what it is to be Samoan, and therefore is necessary if the project team was to gain a richer understanding of the Mapusaga children’s working theories about their own identity, language, and culture.

Each case study child’s story of how their working theories as they relate to identity, language, and culture (and teachers’ interpretations and responses to these) impacted on their learning and participation over time, was unique. The following illustrations of two case study children, Talia and Teri, provide a glimpse into these differences.

Major implications for practice

The findings from this project reflect the broad and complex nature of the working theories young children are developing and applying as they participate in diverse ECE communities. The examples captured in this project, however, are only the tip of the iceberg of children’s ideas and understandings as most of the thinking, ideas, and understandings of young children are not clear to others and therefore remain ‘under the water’—hidden from view. Despite the challenge of surfacing some of what young children are thinking, their working theories about the social world do help mediate (or hinder), engagement in learning and learning with others. It is, therefore, necessary for those working with young children to ensure they intentionally seek to notice, make meaning of, and respond to the expressions of these working theories (Davis & McKenzie, 2016). Practitioners committed to this process will seek contributions from multiple diverse perspectives, and be inclusive of the voices and knowledge all families bring about their child particularly in terms of their cultural ‘islands of expertise’ (Davis & Peters, 2011).

In the early stages of this project, teachers made a conscious decision to tune into and look for examples of children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture in action. This direct act kickstarted a journey toward becoming more culturally intelligent, and as a result more culturally responsive teachers. Furthermore, the data show that the lives and learning of children were also enriched and contributed to their growing cultural intelligence. The process employed by the project team included analysis that explored multiple cultural viewpoints to make meaning of children’s theories. This analysis helped shift what teachers were noticing about what children are making sense of, and how. In turn, this process shifted how teachers responded to children. Teacher-led inquiries also proved to be a similarly powerful means for bringing about new insights, new understandings, innovation, and transformation (Timperley, 2008; Timperley & Parr, 2004; Ministry of Education, 2007). These processes and actions are replicable and adaptable for any teaching environment and are worthy of greater attention.

As teachers became more attuned to children’s theories they listened more deeply and this contributed to them better understanding children’s ideas and thinking. While this wasn’t always easy, teachers felt more focused in their observations and, over time, more ready and able to act. Developing a shared understanding contributed to this heightened focus and shared commitment to action.

Ensuring there are opportunities for children to share their ideas and understandings is critical. Teachers in this study found they needed to create more frequent, richer opportunities for children to share and contribute perspectives. At both centres teachers practised doing this more during their day-to-day interactions with children, and both centres changed significant and subtle aspects of their group times.

At North Beach, teachers intentionally planned conversations and provocations during shared kai and at group hui to stretch children’s thinking. At group hui this included utilising drawing to help children express their ideas and share thinking. At Mapusaga, teachers created opportunities for children to co-construct the telling of Bible stories and to share perspectives about the meaning of these stories during lotu and fanau times. Longer term projects at North Beach meant children had extended periods of time to build their ideas and understandings around superheroes over weeks and months.

Throughout this inquiry teachers tested their own theories and ideas on how to expand children’s thinking, including exploring ways to help children recognise their own superhero qualities and those of their families and whānau.

Designing specific learning experiences created opportunities for children to be positioned as experts in relation to their interests and funds of knowledge from home (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992). This proved particularly important to supporting and nurturing children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture. A critical step in this process was to become more appreciative of the child’s family culture, how closely this relates to the child’s sense of identity, and the positive impact this recognition can have on both the child’s identity and their overall experience (and their family’s experience) as a member of the learning community.

An example of this at North Beach was when a teacher introduced Bible stories to the library corner in response to her growing appreciation of the importance of these stories in some children’s home lives and in affirming their sense of identity as Christian learners. When a teacher at Mapusaga asked a child to bring in a favourite DVD about Samoa, the child watched it at home with their aiga. All the teachers and children watched the DVD together and this helped the teachers better understand the child’s interest in fale’apa, meaning they could respond more meaningfully to her play, questions, and observations.

A focus on the working theories children are developing about others is important. Problematic working theories that bias particular identities, cultures, and languages (including in some cases working theories that bias one’s own identity(ies), language(s), and culture), can prevent quality learning, and mitigate equality of opportunity. Working theories about identities, languages, and cultures that de-legitimise those of learners prevent productive participation, diminish opportunities for respectful collaboration, and thwart learning opportunities for all parties (Derman-Sparks, 1989). Recognising similarities and differences can also contribute to perspective taking: a feature vital to the analysis and critical thinking we seek to develop in life-long learners (Claxton, 2002). Working with young children in ways that helps them to recognise similarities and see differences as ‘normal’ contributes to understanding diversity and addressing inequalities (Siraj-Blatchford & Clarke, 2000). In this project, it was noticed that in some cases the children’s comments about others indicate they are yet to recognise diversity beyond ‘others as same’ (Hartas, 2008) (for example, see Table 1, Making sense of others, “Nora and you are the same”, “Why are all Nora’s family here?”). These examples, alongside the others discussed in this report, remind us that, while young children can develop an appreciation of the identity, language, and culture of others, the ability to recognise what makes a person culturally similar or different from another (beyond skin colour), is likely to require a range of experiences with peoples of many different cultures.

Overall, the findings suggest that creating opportunities for children to share their ideas may include the need for adults to develop new ‘habits of practice’. At times doing this may be challenging or personally confronting. However, what the teachers in this study showed was that when they worked together (and cross-culturally) to examine carefully the everyday teaching and learning taking place in their communities, it almost always revealed both richness and uncertainty and prompted the need for questioning, reflection, and action.

Limitations

Anyone with any experience of working with young children knows that grasping a young child’s evolving ideas and understandings is a slippery near impossibility. A child’s attention to detail can at times be intense and then suddenly absent. In undertaking this study, the project team did not seek to provide absolute certainty; rather, we sought to contribute a perspective to a little studied phenomenon that is children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture. We recognise that our perspectives and experiences are our own; however, we believe these examples provide useful insights into the ways children’s ideas and understandings of identity, language, and culture influence learning. Due to the scope and scale of this project the project team was unable to follow the children’s journeys into school. An exploration of whether the connections of the fau[1] extended to include the influence of this transition on children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture is an area for future research.

Conclusion

This project sought to contribute new understandings to what is known about young children’s working theories about identity, language, and culture and how best to support the development of these theories. The project team discovered much about how the ways identity, language, and culture can be recognised through a working theories lens. As the research project unfolded, the teachers began to better support diversity, and participation, through pedagogy and programme design that became more responsive to more learners. The cross-cultural, cross-site, ‘sister’ relationships embedded in the design and undertaking of this project was a particular feature that contributed to this shift. These relationships made exploring a challenging phenomenon not only a rich and fulfilling experience for the project team, but also activated shifts in thinking and action which may not have been possible otherwise.

While it might not be practical for all teachers and researchers to undertake a project such as this, anyone can decide to collaborate with others to learn about the unique ways of knowing, being, and doing differently. Across the course of this project both adults and children became more culturally intelligent and demonstrated growth in each of Van Dyne, Ang, and Koh’s (2009) four factors of cultural intelligence or CQ:

- Motivational CQ: They showed interest, confidence and drive to adapt cross-culturally.

- Cognitive CQ: They demonstrated understanding of cross-cultural issues and differences.

- Metacognitive CQ: They strategised and made sense of culturally diverse experiences.

- Behavioural CQ: They changed their verbal and nonverbal actions appropriately when interacting crossculturally.

The project exemplifies what is possible when groups choose to undertake cross-cultural collaborative projects and inquiries focused on improving outcomes for all learners. The findings discussed in this report represent the big ideas to emerge from the data. There are many smaller, personal stories of the young children, their teachers, and families that are yet to be told. What should be taken from this report is that there is vast potential in children, teachers, and families ready to be uncovered in every learning community, and that exploring how identity, language, and culture influences this potential is a worthwhile place to start.

Footnote

- A fau is a natural fibre or rope with many strands that is strong and holds things together. The fau has many strands, which gives it its strength and connections. ↑

References

Brooker, L., & Woodhead, M. (Eds.). (2008). Developing positive identities: Diversity and young children. Early childhood in focus (3). Milton Keynes, UK: Open University.

Claxton, G. (2002). Building learning power: Helping young people become better learners. Bristol, UK: TLO.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Donnell, K. (2006). Practitioner inquiry: Blurring the boundaries of research and practice. In J. L. Green, G.

Camilli, P. B. Elmore, A. Skukauskaité, & P. Grace (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (pp. 503–518). Washington, DC: AERA & Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Copenhaver-Johnson, J. (2006). Talking to children about race: The importance of inviting difficult conversations. Childhood Education, Fall, 12–22.

Davis, K. (November, 2015). New-entrant classrooms in the re-making. CORE Education Pro Bono Charitable Research Fund project. Available from: http://www.core-ed.org/thought-leadership/research/new-entrant-classrooms-re-making

Davis, K., & McKenzie, R. (2016). Rainbows, sameness, and other working theories about identity, language, and culture. Early Childhood Folio, 20, 1. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Davis, K., & Peters, S. (2011). Moments of wonder, everyday events: Children’s working theories in action. Teaching and Learning Research Initiative final report. Available from: http://www.tlri.org.nz/moments-wonder-everyday-events-how-are-young-children-theorisingand-making-sense-their-world/

Derman-Sparks, L. (1989). Anti-bias curriculum: Tools for empowering young children. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Drummond, M. J. (1993). Assessing children’s learning. London: David Fulton.

Gee, J. (2008). A sociocultural perspective on opportunity to learn. In P. A. Moss, D. C. Pullin, J. P. Gee, L. J. Young, & E. H. Haerte (Eds.), Assessment, equity, and opportunity to learn (pp. 76–108). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/ CBO9780511802157.006

Hartas, D. (2008). The right to childhoods: Critical perspectives on rights, difference and knowledge in a transient world. Continuum studies in education. London, UK: Continuum.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (2000). Participatory action research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 567–605). London, UK: Sage.

Laevers, F. (1994). The innovative project Experimental Education and the definition of quality in education. In F. Laevers (Ed.), Defining and assessing quality in early childhood education (pp. 159–172. Studia Paedagogica. Leuven, Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Ministry of Education. (1996). Te Whāriki: Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2008a). Ka Hikitia—Managing for success: The Māori education strategy 2008–2012. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2008b). Pasifika education plan 2009–2012. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2012). Me korero—let’s talk. Ka hikitia—accelerating success 2013–2017. Retrieved from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/theMinistry/PolicyAndStrategy/KaHikitia/MeKoreroLetsTalk.aspx

Ministry of Education. (2013). Pasifika education plan 2013–2017. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Moll, L., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132–141.

Peters, S., Paki, V., & Davis, K. (2015). Learning journeys from early childhood into school. Teaching and Learning Research Initiative final report. Available from: http://www.tlri.org.nz/sites/default/files/projects/TLRI_%20Peters_Summary%28v2%29%20%281%29.pdf Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford, UK & New York,. NY: Oxford University Press.

Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Clarke, P. (2000). Supporting identity, diversity, and language in the early years. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Taylor, S., & Bogdan, R. (1998). Introduction to qualitative research methods: A guidebook and resource (3rd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Timperley, H. (2008). Teacher Professional Learning and Development. International Academy of Education Educational Practices Series, no. 18.

Timperley, H. & Parr, J. (2004). Using Evidence in Teaching Practice: Implications for Professional Learning. Auckland: Hodder Moa Beckett. Tuafuti, P. (2010). Additive bilingual education: Unlocking the culture of silence. MAI Review, 1–14. Available from: www.review.mai. ac.nz/index.php/MR/article/viewFile/305/397

Van Dyne, L., & Ang, S., & Koh, C.K.S. (2009). Cultural intelligence: Measurement and scale development. In M.A. Moodian (Ed.), Contemporary leadership and intercultural competence: Exploring the cross-cultural dynamics within organisations (pp. 233–254). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Project team

CORE Education researchers

Keryn Davis Senior researcher keryn.davis@core-ed.ac.nz

Ruta McKenzie Researcher and facilitator

Dalene Mactier Research assistant

Mapusaga A’oga Amata teacher–researchers

Peta Vili

Fa’amavaega Saofa’i

May Crichton

Mara Gase

Havana Vili

North Beach Community Preschool teacher–researchers

Debs Rose

Hayley Beecroft

Munira Sugarwala

Hannah Callingham

Belinda (Bee) Rowlands

Rachael Vincent

Nora Brown

Lynette Halligan

University of Waikato research associates

Vanessa Paki

Dr Sally Peters

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the TLRI for funding this project. The researchers wish to acknowledge the dedication of the teachers of North Beach Community Preschool and Mapusaga A’oga Amata to the project and all that comes with study of this nature. We are also grateful to the children, families, and aiga of these communities for allowing us to share their stories.

Thank you also to our research associates, Sally Peters and Vanessa Paki, Jo MacDonald (NZCER) and the countless other educators, academics, leaders, reviewers, facilitators, colleagues, researchers, and friends who have contributed advice, critique, and feedback to us over the past few years as we pursued this wonderful project.