Aotearoa New Zealand’s attention to adult literacy and numeracy (L+N) education arose from the results of the OECD / Statistics Canada International Literacy surveys begun in the mid-1990s, when, as a nation, we achieved unexpectedly low results for L+N proficiency. The Government responded with an adult L+N strategy (Ministry of Education, 2001) that spellt out initiatives in building professional capability for delivery, improving the quality of the system, and ensuring that larger numbers of learners could access L+N learning. Over the next 10 years, further measures were included, such as credentialising tutors, expanded funding for educational provision, a national literacy centre housed in the University of Waikato, a national set of L+N learning descriptors, and a standardised, skills-based national assessment tool.

In this context, Literacy Aotearoa, our partner on this project and the nation’s largest adult literacy provider, serves approximately 8,000 adult L+N learners across the country, and more than 50% have no school qualifications (Literacy Aotearoa, 2018). For learners who enrol at a Starting Points level, learning progress can appear glacial from an external perspective, especially when learners are dealing with a range of social issues. While they may not all attend qualification-certificated programmes, Literacy Aotearoa is dedicated to ensuring that their learning experience is successful and valuable to their employment, family, community, and further learning opportunities. It operates from a Tiriti o Waitangi framework that is in accordance with Tino Rangatiratanga guided by Manaaki Tangata.

Along with growing interest in the broad outcomes of L+N learning, Literacy Aotearoa has investigated alternative ways to express the value of L+N learning beyond the mastery of skills by focusing on the impact of L+N in people’s lives. Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga: A model for measuring wellbeing outcomes from literacy programmes (Hutchings, Yates, Isaacs, Whatman, & Bright, 2013) emerged out of earlier research that presented narratives of adult L+N learners’ success, and its impact on them, their tamariki, mokopuna, and wider whānau members (Potter, Taupo, Hutchings, McDowall, & Isaacs, 2011). Success for learners was demonstrated by learners taking control of their lives and participating more in their whānau commmunity lives, and the labour market, and experiencing increased sense of self, enhanced understanding of others, and greater independence. A process for systematically recording Māori learners’ stories of broad personal and whānau-related outcomes and mapping them to learner-identified concepts of wellbeing, grouped by the researchers into a set of descriptive wellbeing indicators, was then trialled. The Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga wellbeing indicators are:

Motivation to learn and teach others

Increased ability to fulfil roles and responsibilities to the whānau

Increased interest in, knowledge and transfer of Māori literacies

Stronger cultural identity

Increased aspirations for self and whānau

Identifying and creating our own learning abilities and teaching opportunities

Greater personal confidence

Māori ways of understanding the world

Increased spiritual and emotional strength

Enhanced understanding of self in relation to others

Developing better relationships with others

Greater sense of positivity and happiness

Increased interest and capacity to strengthen whānau

Sense of connectedness and inclusion

Increased self-esteem

Increased self-determination (Hutchings et al., 2013, p. 15)

As a process, Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga involves conversational interviews between tutors and individual learners midway and at the end of the L+N programme. The conversations begin with whakataukī which draw the learner in and indicate the kaupapa Māori essence of the assessment process. Together, tutors and learners explore the impact of the L+N learning on the learners and their whānau and map the identified impacts to the wellbeing indicators. At the end of the programme, learners complete a brief written survey inviting their personal assessment of new skills, improved confidence and work chances, educational enhancement, and hopefulness about their future. Through these processes, learners become more aware of, reflective, and articulate about broad L+N programme outcomes important to them in their lives. Tutors welcomed the opportunity to record these benefits but time demands of the interview component were burdensome.

Our interest in Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga comes not only from its value as a systematically trialled starting point for conceptualising and reporting wellbeing-related outcomes of L+N learning. Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga also attests to the important value of Māori contributions to deeper, more socially aware understandings of the complex ways that adult L+N learning impacts on people’s lives. Meanwhile, however, the historical disenfranchisement of Māori endures. It allows for unfair advantage among society’s dominant groups, strains the social fabric, prevents people from reaching their potential, and rationalises social inequality, weakening society in many ways. We see Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga as a pedagogy for identifying and supporting learners’ broad outcomes with positive implications for the wide diversity of marginalised adult L+N learners who have a range of life experiences in Aotearoa New Zealand. Simultaneously, we and our partners recognise that the time demands need to be addressed for the model to be sustainable. As well, further exploring conceptualisations of wellbeing could contribute to the model’s relevance to all learners in L+N programmes. The TLRI study set out to address these issues. It focuses on three areas to investigate further: manageable processes of developing and integrating meaningful outcomes in programmes; wellbeing-related outcomes identified by a range of diverse learners; learners’ ownership of their L+N learning and wellbeing. To this end, we developed the following research questions:

- How can a wellbeing framework be further developed and incorporated into adult L+N programmes in ways that engage tutors and learners in broad wellbeing outcomes, and that are meaningful and manageable for them?

- What broad wellbeing outcomes can adult learners identify as a result of their engagement in L+N learning?

- How does the use of a wellbeing framework help learners assume ownership of their continuing learning?

Conceptualising literacy and numeracy

The past 20 years of research-based theories of L+N and learning have informed our project. We draw on several established and emerging key concepts in the field. Most centrally, the way we understand words and numbers in use depends on more than vocabulary knowledge, grammar, and mathematics skills. Early this century, well-known literacy researchers such as David Barton, Mary Hamilton, and Roz Ivanič (2000) argued that how people make sense of what others say, hear, read, write, and calculate depends a great deal on context and social convention. More recent work by Richard Edwards (2009), for example, defines context not as container-like settings, but as entities that arise through shifting relationships and multiple background factors that participants bring to communication. Relationships among people, places, times, and L+N artefacts (e.g., new media devices) figure in their L+N practices and in how people make sense of L+N. As well, participants’ diverse experiences, cultures, history, current circumstances, and resources dynamically influence the communication and the context (Barton, Appleby, Hodge, Tusting, & Ivanič, 2006). Finally, the notion of agency as “the socioculturally mediated capacity to act” (Ahearn, 2001, p. 112) through and within activities involving L+N is expanded and made real through the complex, shifting relationships in contexts. It is no longer adequate to consider agency as an individual trait but as emerging through relationships. All this presents a picture of L+N contexts as fluid and multifaceted.

This perspective on the nature of L+N also has implications for L+N learning. Well-established adult learning theory maintains that adults’ willingness to engage in learning is contingent on educational programmes being relevant to and meaningful in their lives (Rogers & Horrocks, 2010). It is also contingent on pedagogies that take into account people’s complex lives as adults in their own right, as parents, as family and community members, and as citizens; that is, the contexts of their lives. The importance of attention to diverse cultural contexts is brought to the fore in the Māori Adult Literacy Working Party’s publication, Te Kāwai Ora: Reading the word, reading the world, being the world (2001). The authors suggest literacy is the ability to read and interpret the world through symbols, nonverbal communication, artefacts, and other media. It includes the ability to be bi-literate where Māori and non-Māori can function in both worlds. Moreover, in formal educational settings, programme content, organisational systems, and staff values and beliefs add to contextual elements that shape participants’ learning.

Conceptualising wellbeing

As a starting point for conceptualising wellbeing for this study, we agree with Shah and Marks (2004) that “one of the key aims of a democratic government is to promote the good life: a flourishing society, where citizens are happy, healthy, capable and engaged—in other words with high levels of well-being” (p. 2). In just and fair societies, this aim would apply to every citizen. Such societies would necessarily value diversity (e.g., in culture, ableness) and despise inequity (e.g., in food access, housing adequacy). The aspiration of a high level of wellbeing for every citizen is evident in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD’s) Better Life Initiative (OECD, 2013) and in our government’s related Living Standards Framework (Karacaoglu, 2012). Recent work by the New Zealand Treasury in which wellbeing is expressed simply but meaningfully as “the capability of people to live lives they have reason to value” (Sen, 2003, as cited in The Treasury, 2018, p. 8) suggests the presence of this deeper understanding. This is a view of wellbeing that we share and welcome.

A key influence on national articulations of wellbeing has been Mason Durie’s (1998) Te Whare Tapa Whā model. Widely referenced in health and education for over 20 years and built upon by other scholars, it underpins Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga. A more holistic and unified concept than the tendency in Western thinking, wellbeing for Māori includes physical, mental, spiritual, whānau/whakapapa, and whenua dimensions (Blissett, 2011; Mark & Lyons, 2010). Individual wellbeing is inseparable from whānau wellbeing and is intricately connected to the wellbeing of all living things and the environment. Important outcomes of L+N learning for Māori are the contributions they can consequently make to whānau, hapū, and iwi.

We have added to our lens Nelson and Prilleltensky’s (2010) domains of personal, relational, and collective wellbeing as a further means of broadening the ways wellbeing might be thought about. In this model, wellbeing is characterised at the personal level by features such as self-esteem, confidence, choice, independence, and civic and political rights; at the relational level by embeddedness in networks of supportive social relations and environments (interdependence); and at the collective level by people’s access to the basic resources of society (Nelson & Prilleltensky, 2010). Furness’s (2013) study of wellbeing outcomes of family literacy programmes drew on both Nelson and Prilleltensky’s framework and Te Whare Tapa Whā; both were helpful in understanding the broad impacts of L+N learning on the diverse participants in this study.

Research design and methods

The methodological principles of this 2-year project were drawn from design-based research (DBR). In DBR, research and development occur in an iterative cycle of design, implementation, analysis, and redesign (Baumgartner et al., 2003). DBR must account for how designs work in actual teaching and learning contexts, provide implications that are relevant to practitioners, and be able to document and link implementation to valued outcomes. The DBR approach helped us fine-tune the planned design elements at the outset.

We wanted the design to fit with the variable programme features and to be adaptable as participants’ conceptualisation of wellbeing outcomes expanded and as recognition of their relevance in L+N programmes increased. DBR is also characterised by the interweaving of theory development and practice development, highly relevant as we sought to expand theories about the role of wellbeing concepts in recognising, valuing, and enhancing broad outcomes in adult L+N programmes.

We worked with the Literacy Aotearoa leaders in designing the research, interpreting the data, and finalising the design for Year Two based on the results from Year One. The study programmes were selected from an initial list provided by Literacy Aotearoa of programmes that were within a 2-hour drive for the researchers and typically had students of a mix of ethnicities. We chose three programmes with varied focuses in Year One (one programme did not complete the research programme). We continued with the other two programmes in Year Two and added two others. The mix of programmes included cooking on a budget and computer skills and communication. L+N content included reading, writing, speaking, listening, and numeracy. Five tutors and 25 learners were involved over the 2 years. Learners were mainly non-Māori; three were Māori and one was Pasifika. Learners ranged in age from 18 years to retirement. Table 1 below summarises the programmes and participants.

| Programme | Years | Programme context | L+N content | No. of students | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Computing for learner needs and interests | Computing skills including reading, writing, and numeracy for learnerspecific needs and interests (e.g., emailing family) |

3 | 3 non- Māori/ Pasifika |

| 2 | 1, 2 | L+N related to further learning, employment, and personal needs and interests |

Mainly open polytechnic programmes and Pathways Awarua involving school-like reading, writing, and numeracy |

6 | 5 non-Māori/ Pasifika; 1 Māori |

| 3 | 1, 2 | Communicationfocused L+N | Communications skills, basic literacy, and numeracy of interest to the learner (reading, writing, spelling, vocabulary), driver’s licence, job preparation, curriculum vitae |

6 | 1 Māori, 1 Pasifika, 4 non-Māori/ Pasifika |

| 4 | 2 | Healthy cooking on a budget | Cooking economically, multiplying/ reducing recipes, measurement, quantities, managing household budget |

7 | 1 Māori, 6 non- Māori/ Pasifika |

| 5 | 2 | L+N for special needs adults | Writing personal narratives, reading, writing, and numeracy for managing daily life, computing, expanding the learners’ worlds, and increasing independence through reading, writing, talking, listening, and numeracy |

3 | 3 non- Māori/ Pasifika |

| Totals | 25 | 3 Māori, 1 Pasifika, 21 nonMāori |

Year One design

We launched the project by meeting with Literacy Aotearoa leaders and the programme managers and tutors. We discussed the aims of the project and the planned design elements and jointly finalised some element details to fit with each programme’s content and organisational characteristics. This step was important as a key focus of the project was identifying what was required in order to recognise and record wellbeing outcomes that were meaningful and manageable for learners and tutors. The design elements follow below.

Design element 1: Tutors’ broad understanding of wellbeing and wellbeing outcomes. Literacy Aotearoa leaders explained the aim, content, and processes of Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga to the tutors along with the underpinning conceptualisation of wellbeing and the descriptive indicators. We led a discussion on Nelson and Prilleltensky’s (2010) personal, relational, and collective model of wellbeing. The aim of these discussions was to facilitate a broad understanding of wellbeing outcomes that would enable Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga to be built on.

Design element 2: Overt valuing of wellbeing outcomes and providing a reference point for reflection. We conducted a workshop about how the tutors could support learners to develop personal graphic and/or textual social network maps. The purpose of this activity in the classroom was to help learners recognise that wellbeing outcomes are valued in the programme and to provide a point of reference for learner reflection on their L+N learning, what they identified as important in their everyday lives, wellbeing outcomes, and the links among them. For example, such reflection might identify that writing practice had enhanced their support of their children’s school learning; learning to navigate the internet had helped them access their entitlements from government agencies. Such reflection would provide practice for the planned online discussions (Design element 4).

Design element 3: Ongoing attention to wellbeing outcomes and their relationship to L+N learning. We discussed ways the tutors might pay attention to wellbeing outcomes and their relationship to L+N learning as a natural and ongoing part of classroom discourse. Ideas included the tutors extending conversation by asking questions and pointing out observed wellbeing outcomes and connections to L+N.

Design element 4: Identifying, reflecting on, and recording wellbeing outcomes. Learners were invited to take photos of events in their lives where L+N was involved, upload them to a class Secret Facebook Group, and talk about them as they had the examples from their personal maps (Design element 2). These processes—photo elicitation and Facebook—were to be trialled in Year One as a mechanism for regular reflection on L+N learning, wellbeing outcomes and their links, and for systematically recording them. The tutor’s role was to support technical aspects of the practice of reflection and learner writing. We were to provide technical, strategic, or conceptual support to the tutors as needed. Learners could add the record of wellbeing outcomes generated in the Facebook posts to their learning e-portfolios where these were in use.

Year Two design

We began Year Two with a meeting of tutors, Literacy Aotearoa leaders, and ourselves to review progress and orient the new participants. Year One experiences led to design changes in Year Two. First, tutors varied considerably in their attunement to wellbeing, partly related, it seemed, to how obvious the links to wellbeing were in the content and focus of the particular programme. Consequently, we increased our contact with tutors in order to provide more support to embed attention to wellbeing outcomes. More time with tutors enabled more discussion of their ideas on what would work for them and their learners. Second, the taking, uploading, and talking about photos on Facebook proved problematic for privacy and technological support reasons, and Facebook was abandoned. Instead, tutors instituted new mapping exercises and more class conversations on learning, wellbeing, and their links along with traditional journaling intended to capture links between learning and wellbeing outcomes. They also expanded existing formal recording processes to encourage reflection and recording of wellbeing outcomes. Procedurally, the returning tutors explained more about the project to the learners in advance of our first visit than in Year One to help establish the valuing of wellbeing outcomes in the learners’ minds. The approach to data analysis was the same as Year One with the addition of Design element 5: Mapping to Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga undertaken by us.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected through a short 5-point Likert-scale emoticon learner survey following the mapping and through learner focus groups, tutor interviews, classroom observations, and review of Facebook posts and/ or learner journal entries at the midway and endpoints of the programme. The survey data were dealt with manually in Year One, found unreliable, and discontinued. Following Braun and Clarke (2006), the qualitative data were coded from the theoretical perspectives of literacy as social practice and wellbeing as a holistic, integrative concept and as relevant to the nuances of our research questions. Our coded data were collated into potential themes that were checked to ensure they made sense in relation to the coded extracts and the entire data set. Thematic maps generated were refined through further cycles of analysis and checking. An important part of the process was sharing the collated data with the Literacy Aotearoa leaders, who contributed valuable insights. Table 2 below shows how each research question was answered.

| Research question | Data source | Focus of analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 1. How can a wellbeing framework be further developed and incorporated into adult L+N programmes in ways that engage tutors and learners in broad wellbeing outcomes, and that are meaningful and manageable for them? |

Interviews / focus groups with tutors and learners. Classroom observations. Online interactions between tutors and learners. |

Ease or difficulty; enablers and constraints for tutors to:

Learners’ responses to:

The nature and extent of learners’ engagement with wellbeing |

| 2. What broad wellbeing outcomes can adult learners identify as a result of their engagement in L+N learning? |

Interviews/focus groups with tutors and learners. Classroom observations. Online interactions between tutors and learners. |

Positive and negative changes in the:

Meaning L+N learning held for learners in their everyday lives. |

| 3. How does the use of a wellbeing framework help learners assume ownership of their continuing learning? |

Online presentations and interactions. Journal entries. Mapping to Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga. |

Changes in learners’ articulation of how their L+N learning was enhancing their lives. Changes in learners taking actions that enhance quality of life for themselves, their families, their communities. Learner agency across personal, relational, and collective domains. |

Findings about processes in Years One and Two (RQ1)

In presenting the findings for RQ1 we describe the actions that were taken in the programmes over the 2 years, what occurred as a result, what worked well and problems encountered. We then summarise and draw conclusions about the value and manageability of the actions.

Tutors’ broad understanding of wellbeing and wellbeing outcomes varied

Tutors’ broad understanding of wellbeing and ideas about wellbeing outcomes were variable in that they drew on their respective backgrounds and experiences and expressed diverse notions of wellbeing. One tutor, having taught communication skills to polytechnic students, saw wellbeing as at least partly mediated through communication styles such as passivity, assertiveness, or aggression. Although all the tutors included L+N skills in their programmes, one concentrated on L+N skills mastery and on officially recognised accomplishments, emphasising that they would be needed for future work life, a common approach in L+N teaching. Learners engaged well with this approach when official accomplishment and consistent, generous tutor support were interwoven. Ongoing attention to caring relationships, family responsibilities, and family wellbeing comprised the tutor’s approach in the L+N cooking class. In the special needs programme, learners did journal writing, leading to an expanding sense of participation in the world and positive emotional states.

Valuing of wellbeing outcomes and orienting the learners were trialled through mind mapping

As we began our research in each of the programmes, we asked learners to develop maps of what was important to them in their everyday lives, an activity they seemed to find engaging. The tutors agreed that the mapping was valuable in orienting learners to thinking about their learning in relation to what was important to them in their everyday lives and thought the maps would be useful as a reference point for later reflection. They thought the guiding question, “What is important to you in your everyday life?” “worked really well”. However, the maps were often not completed in the allotted time and, even when completed, were seldom referred to again by the tutors. A few learners did keep them on hand and quickly recalled their contents in our focus groups.

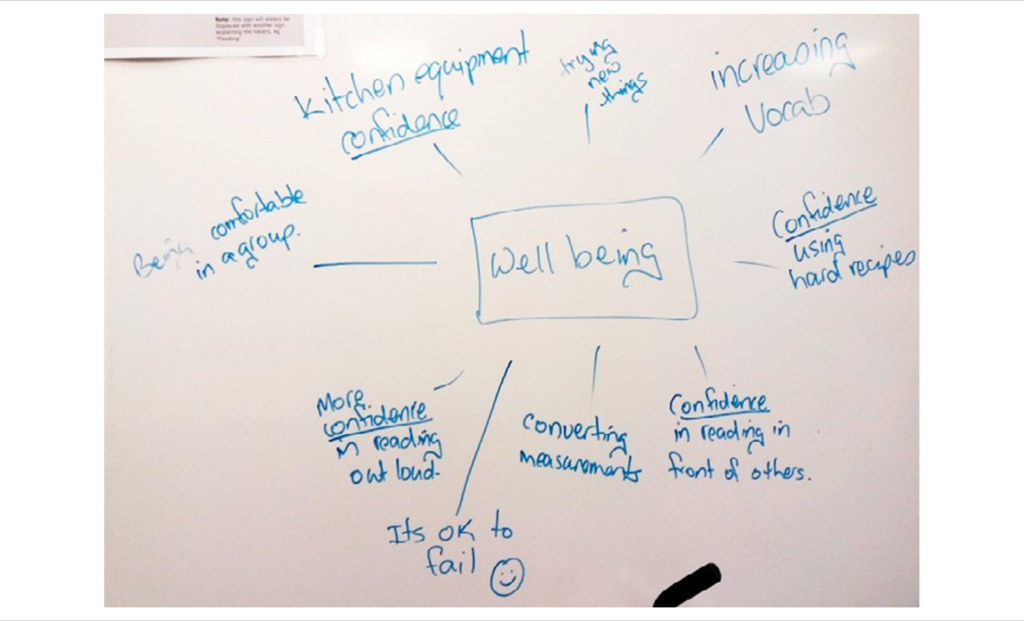

To orient learners to think about wellbeing in Year Two, learners in one group were asked to create mind maps on the value of learning and the nature of wellbeing. It was reported that learners engaged well with this activity. They tended to describe the value of learning as goals; for example, “so I can get a job and know what I can do”, personal capacities like “resilience”, or everyday responsibilities such as “feeding a lot of people for a little price”. Some of these statements reappeared in learners’ recording of wellbeing outcomes. Cooking class learners chose to collaboratively describe wellbeing-related outcomes from their programme (see Figure 1 for their class map). Similarly, these outcomes reappeared in their personal storying of their everyday lives.

Figure 1. Class map of cooking programme wellbeing-related outcomes

Tutors developed ways of paying attention to wellbeing outcomes that were relevant to L+N learning

There was some ambivalence amongst tutors about their own understanding of wellbeing and wellbeing outcomes as noted in the ways they discussed wellbeing and wellbeing outcomes with learners throughout the programme. They encouraged learners to think about wellbeing outcomes by asking them to consider their feelings about what they learned and how they were using what they learned in their daily lives. The tutors often wanted to explore these concepts further with us, and over the course of the project we noticed that tutors’ attention to wellbeing outcomes increased.

In the L+N cooking programme, wellbeing was expressed largely in terms of effectively managing household and family food responsibilities. It was explicitly threaded throughout the class time. Further, the tutor friended class members on Facebook, shared family stories, invited family members, her own and learners’, into the class. In another programme, needs voiced by the learners themselves were addressed in the programme. One example arose from a learner who was anxious about reading the airport signs when travelling on her own. The class visited the local airport, took photos, and made practice vocabulary cards. The learner subsequently reported managing well on her travels. In a third example, the tutor asked learners to observe and analyse the communication practices of others outside of class. Both the learners and the tutor reported this as a valuable way of understanding the effects of communication styles on relationships. Another tutor stated that she paid most attention to relationships within the class and saw achievements as most important for future wellbeing.

Regular group conversations about learning outcomes (e.g., during morning tea break or the first meeting of each week) were reported to help tutors maintain attention to wellbeing. Tutors opened conversations by asking about learners’ wellbeing since the last conversation. Tutors noted that spending informal time with learners provided opportunities for wellbeing outcomes to surface as a natural dynamic of strong relationships.

Tutors had variable success eliciting L+N-wellbeing discussion in everyday classroom interaction. Teaching demands may have impeded the spontaneous attention to and recording of wellbeing outcomes. Some tutors were able to make notes immediately after class. Others sometimes found time when learners were completing the programme’s official Record of Learning (RoL) where they wrote briefly about each day’s learning. Still others pointed out challenges of remembering or finding time to record or further explore spontaneous expressions of wellbeing.

Paper and talk were preferable to Facebook for identifying, reflecting on, and recording wellbeing outcomes

In Year One, we offered the learners prompts and ideas for their posts to Facebook. One group of learners enthusiastically uploaded relevant events that occurred in their lives. These learners seemed pleased with our brief responses to their posts. Facebook posts became part of the group sharing and discussion.

Two groups declined to use Facebook mainly for privacy reasons. One tutor noted that resistance came

“because we had a group from Women’s Refuge and they were very, very private people. A learner doesn’t use Facebook at all and that put him off; [he] thought his friends were going to see it … and another learner just never wanted to.”

For those who used Facebook, there appeared to be some anxiety about writing correctness, which may have diverted attention from the goal of connecting L+N learning and wellbeing outcomes. As well, some tutors often scribed for the learners, which may have influenced their posts. In addition, the technology did not work smoothly much of the time, especially photo uploads, and the Secret Group proved not to be consistently private. Indeed, we chose to end its use for the learners’ safety. One group that did not want to use Facebook began to use emails to share their L+N learning and its links to wellbeing with us. This group also engaged in a good deal of conversation with the tutor and the other learners in the group.

Tutors also varied in their enthusiasm for Facebook from “using Facebook pages is brilliant” to “I was worried myself, cause I don’t really do Facebook either.” For the tutor who used it, photos were thought to be an essential component, with the tutor noting that “they link back to the experience; they’re personal to them. They are important to them. I think that’s an essential part of it.” However, the time needed to support the learners in this activity was thought to often be too great.

In Year Two, these processes were most often tutor-led. Learners in one programme especially enjoyed the journals, making regular narrative entries about their everyday lives. In the previous programme, they had worked primarily on discrete skills, and the tutor noted that they welcomed this shift. They actively drew on various resources to use language correctly in their writing. Their tutor reported that their writing processes became more interactive, and they were thoughtful about content and organisation. These stories were eventfocused; one exception was at least one learner in another programme who wrote extensively and deeply about wellbeing in the journal. Upskilling tutors set aside particular times during the week to talk with learners about broad learning outcomes, which they butressed with the additional RoL question.

Learners in one group organised a collaborative whiteboard mind map of their L+N outcomes at regular intervals. They worked together enthusiastically as a class to nominate and discuss them. In the L+N cooking class, learners identified specific practical skills that they implemented at home. They also noted a new sense of self-efficacy such as “speak[ing] out in front of others”. The tutor felt that reflecting regularly on wellbeing about every 2–3 weeks was about right. This process seemed most effective and participatory.

In some groups, a second RoL learning outcomes question was added to the document used by learners to record their daily learning. Learners described classroom activities and learning topics for the original question. They were also asked to comment on their everyday uses of their learning. Responses to the extra question showed continued attention to skills improvement (e.g., “Learning capital and full stops. It is important so someone can read it” [tutor scribed]). The tight formatting of the RoL document constrained what could be said. Tutors and learners often felt rushed at the end of the day when they were completing it.

Tutors across the programmes showed a strong ethos of valuing people and of creating a supportive class community

The tutors and programme staff unequivocally showed a strong ethos of valuing the participants as vibrant people, of genuine concern for their welfare and wellbeing, which reflected whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, and reciprocity. They spoke regularly of seeing them as whole people with multi-faceted lives (not just as L+N learners) and, relatedly, as having many strengths and capabilities. We observed that tutors were welcoming and displayed an interest in learners’ wellbeing.

Learners also reported a strong sense of community in their programmes. They cited several ways that tutors enhanced their sense of self-worth and belonging: unequivocal acceptance of everyone, patience and dedication to their personal learning; development of a supportive peer culture; acceptance of mistakes as natural; and concern for and sharing of family life. As well, learners and tutors reported working collaboratively to develop group protocols for mutually respectful interaction.

This existing ethos clearly contributed to learners’ wellbeing simply by being in the programme. It also contributed to the enthusiasm with which the tutors embraced the challenge of strengthening their attention to wellbeing outcomes.

Tutors’ noticing and recording of wellbeing outcomes varied

We learned that, to varying extents, tutors noticed and recorded wellbeing outcomes as part of their regular reflective practice and planning. The variability appeared related to tutors’ existing practices. For example, a tutor who shared very rich examples of wellbeing outcomes spent considerable time reflecting and planning after each session with a broad concept of valuable outcomes in mind.

Summary of process findings

Tutors’ concepts of wellbeing, which underpinned their teaching activities, were influential in the recognition, valuing, and enhancing of wellbeing outcomes in their programmes. Posing questions like, “What’s important in your life?”; “How is your L+N learning useful in your everyday life?” seemed more accessible for learners and productive than focusing on definitions of wellbeing and its manifestation in their lives. On the whole, learners’ collaborative discussions about wellbeing outcomes seemed more fruitful than individual written reporting.

To enhance manageability, tutors needed opportunities to consider wellbeing in the light of programme content and goals. Tutors benefited from thinking about how to provide support that would enable deeper reflection.

Mind maps about L+N learning and everyday broad outcomes were most productive, especially when undertaken collaboratively and regularly, and group conversation enriched the results. Although potentially valuable and manageable, mind maps about what is important in your everyday life tended not to be pursued. Journaling provided an easy way in for learners anxious about writing, but learners needed encouragement and guidance to move from writing narrative accounts to reflecting on the meaning of their learning in their lives. The additional learning outcomes question in the RoL was not as productive as the mind maps, despite providing individual responses. Although the RoL was to be completed at every class, it often was not. Learners did not seem inclined to reflect more deeply about the additional question. In every programme, tutor practices showed a consistent, ongoing ethos of valuing learners, which seemed crucial to trust and openness in the group.

We observed three elements that supported learners’ reporting of wellbeing outcomes and their links to their L+N learning: 1) tutors were able to develop a sense of connectedness and belonging among the learner group members; 2) tutor-instigated, regular (2–3 weekly), collaborative discussion-based mind mapping on L+N learning linked to wellbeing outcomes; and 3) overt and regular linking between their L+N learning and wellbeing outcomes as a natural part of classroom conversation. Learners’ forthcoming and reflective responses in the practical programmes could be partly attributable to the immediacy of the programme’s tangible aims and outcomes. We found that learners shared richer descriptions of wellbeing outcomes when we invited them to explore their experiences more deeply in focus group discussions, which some tutors also followed by setting aside regular times for discussion.

Findings about wellbeing outcomes in Years One and Two (RQ2)

The wellbeing outcomes discussed and recorded by the diverse learners in our study and their tutors included improved competencies, positive behavioural changes, an enhanced sense of themselves, and better relationships. We have clustered the many examples into accomplishments, relationships, self-worth, belonging, independence, and optimism. We found a number of alignments between these outcomes and the Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga descriptive wellbeing indicators. These are identified in quotation marks alongside our findings.

Accomplishments

- Increased competency in skills and knowledge. Learners and tutors reported acquisition or enhancement of skills and knowledge. They included: 1) generic literacy skills and knowledge (reading, writing, spelling, vocabulary, maths); 2) more specific goal-oriented competencies (job interview and job search, being assertive, cooking, reading airport signage); and 3) greater understanding of broad societal concepts (personal health, workplace diversity).

- Achievement of official markers of accomplishment. “Increased interest in, knowledge and transfer of Māori literacies”. Learners worked on and completed Open Polytechnic programmes, Pathways Awarua, and unit standards. One tutor commented, “She likes to know she is learning something new always. She likes to feel as if she’s accomplishing things.” Another learner enrolled in a te reo Māori programme, regularly sharing his progress with the group, saying:

I went from school, to school … I couldn’t do the maths, writing, spelling … so when I start coming here, I get the support from [tutor] plus our group. It’s given me more confidence to be able to go onto the computer, and do the Pathway, and able to do the maths, and the homework that we have to do. Nobody has ever done that for me … but also Mauri Ora, when I did the Māori course … Coming here is the best thing I’ve ever done.

- Enhanced support of whānau. “Increased ability to fulfil roles and responsibilities in the whānau/Increased interest and capacity to strengthen whānau/Motivation to learn and teach others”. Learners often identified teaching family and children as important to their wellbeing. One reported, “I’m teaching my son how to cook now. So everything I’m learning, I’m showing him.” Learners also talked about better management of family responsibilities. As one said, “now we’re actually looking at labels and what’s actually in our food”.

Increased self-esteem, self-efficacy and sense of self-worth

“Greater personal confidence, increased self-esteem/Increased spiritual and emotional strength”. Learners described having an increased sense of self-worth and feeling braver and more willing to give things a go as a result of the programme support. One reported:

For my application forms, I had to do a small video interview. That was hard. That was right out of my comfort zone … But I made it through. It was just like, “Whew! I learnt to do it, type thing.” Really good, eh? Really, really, really good. I was on cloud nine.

Signs of wellbeing were affirmed through storying about positive everyday family and social relationships and reliving memorable events. One learner wrote briefly, “Friday the 31st of August was Cancer Society Daffodil Day. I was selling daffodils, teddy bears, pens and bags at the hospital.” [published in the organisation’s book of learner writing]

Belonging/whanaungatanga within the programme

“Sense of connectedness and inclusion /Increased aspirations for self and whānau”.

- Sense of inclusion. Class members talked about the importance of their sense of inclusion in their programmes and of seeing each other outside class, especially in smaller communities. A Year Two learner pointed out that they were “all friends on Facebook now”. Another described the programme as “communication, honesty, trustworthy—what we share in the group is trustworthy and honesty”.

- Sense of safety. Tutors also noted that some began to interact more readily in the classroom. For example, one learner’s arrival in the class was described as “not look[ing] at anybody, never smiled, didn’t interact … and you’ll see in her journal entries that she very soon started writing that she felt safe here, and that she looked forward to coming”.

- Flow-on effects to whānau. In one class, the son participated when he was not at school. A learner’s baby was accepted in class and cared for by class members (mother could not attend otherwise).

Autonomy and independence

Learners reported greater autonomy in reading and calculating to accomplish everyday tasks, such as shopping, due to improved skills. They described greater independence in activities such as travelling and managing life (e.g., understanding official correspondence and public signage). One told us that she didn’t “have to go and ask Mum and Dad what this piece of paper means as much … important letters you get in the mail”. She added, “Now I actually can understand it … That’s how much my reading’s improved—a lot!” Another learner spoke about new independence in food shopping. She said:

I can go to the shop and look for something I need, and I know I can find it without taking someone with me to look for it … Like in Pak’N Save, before I would just grab … and half the time it was wrong, but now when I need something, I know what it is now. And it makes you look at the prices more too.

Optimism and planning for the future

“Greater sense of positivity and happiness”. One learner explicitly identified L+N as a springboard for future plans. In her words, “I put a plan in my heart, my body, my mind, that I need to do this first; work more on my numeracy then once I feel I am able to do this, I want to move forward.”

Summary of wellbeing outcomes findings

Learners reported positive wellbeing-related outcomes from improved L+N skills and associated practices and from supportive tutors and classroom communities.

Accomplishments, improved relationships, and sense of self-worth, belonging, independence, and optimism tended to be interwoven and mutually influential rather than discrete. Unsurprisingly, we found many areas of alignment with Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga, particularly around personal and family relationships, which were at the forefront of wellbeing outcomes in both sets of research.

Findings about ownership of learning (RQ3)

We looked at learners’ articulations of how their L+N learning was enhancing their lives and at their decisions and actions that enhanced quality of life for themselves, their families, and their communities. They spoke of meaningful ways that they applied L+N learning in their everyday life and in their relationships outside the classroom. They identified outcomes from the relationships with each other and their tutors that positively carried over into their lives outside the classroom.

As reported in earlier sections, there was evidence of greater personal autonomy and agency from L+N learning. Greater independence was seen in how some learners conducted activities such as travelling, shopping, searching the internet, or managing other daily routines. Others reported making important decisions in managing relationships with whānau, classmates, and community members, which they followed through with plans and new behaviours beyond the classroom.

While we welcomed these outcomes, we would argue that the evidence from our research calls for shifting away from a traditional perspective on agency itself and the notion of ownership of learning. As signalled in the section on conceptualisations of literacy and numeracy, new theories put contextual features at the forefront rather than in the background. To elaborate, there is a current recognition that our lives are powerfully shaped by and integrated with multiple globalised networks, relationships, and modes of communication (Fenwick & Landri, 2012). Accordingly, agency and ownership of learning are seen as distributed across an assemblage of forces rather than as personal characteristics or individual learned outcomes.

Thus, we want to acknowledge the part played in our learners’ agency from relationships with others— classmates, family, and tutors—from the materials used in their programmes, and from available contexts outside the classroom. For example, the tutor supported all the learners as people and as learners, which created a sense of self-worth and self-efficacy to take initiative. Classmates worked together to engage collaboratively in the programme, and class members shared the overall menu tasks. Moreover, the nature of the L+N cooking programme offered ready applications of learning through everyday food shopping and cooking. Informal class sharing of the food cooked in each class session affirmed learners’ accomplishments, and Facebook friends and mobile phone photos provided a platform for these learners to display their class cookery results. In informal class sessions that we observed, learners shared their experiences trying out recipes at home. In all these ways, agency was shared among the learners and the tutor.

There were marked similarities to Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga in terms of articulations of wellbeing-related learning outcomes and taking action to improve their lives. Learners in both studies passed their learning on to family members, encouraging healthier eating and improving their vocabulary. They spoke of being “confident” enough to ask for help from others and of making concrete plans for improving their L+N learning to help their children. At the same time, the current study more explicitly showed the processes and relationships involved in learners’ wellbeing outcomes, as addressed throughout the Findings sections of this report.

Discussion and conclusions

Processes

Over the 2 years of this project, tutors and learners trialled, reviewed, and refined a number of processes for enhancing attention to wellbeing outcomes in their programmes. Social media was trialled, but classroom conversations, mind mapping, and journaling, fashioned to suit each programme, formed the core of the processes tutors and learners persisted with to achieve this goal. We observed new and existing practices that came together to engage tutors and learners in broad wellbeing outcomes in ways they found meaningful and manageable.

For tutors who were regularly linking L+N learning to their learners’ everyday lives, involvement in the project meant that they paid more attention to opportunities for such links to be made, although it varied. Where the content involved practical aspects of daily living such as cooking it was relatively easy to make the connection between the learning and positive change in the learner’s life or, indeed, the lives of other family members or the family as a unit. When the content was de-contextualised L+N skills for credentialising, the connection tended to centre on the accomplishment of officially valued standards or to characteristics the learner displayed in achieving standards valued in the workplace, such as persistence. Links to other aspects of people’s lives that were important to them tended not to be made. Other factors that appeared to influence the nature and extent of linking L+N learning to wellbeing outcomes appeared to be the tutor’s own orientation; that is, how strongly they were attuned to the possibility of such a connection and were looking for it. Importantly, tutors also often wanted to explore with us what wellbeing meant and what wellbeing outcomes might look like, which we found to be fruitful.

Collaborative discussion and recording of wellbeing outcomes that took place regularly emerged as an essential component of effective embedding of attention to wellbeing outcomes. The value the recorded outcomes held seemed closely related to the tutors’ orientation to wellbeing within the programme and the extent and nature of classroom conversations while the learners were recording. Relatedly, tutors who practised consistent encouragement, trust, and dedication to learners’ success and constructed a supportive learning community were clearly integral to safe and productive attention to wellbeing outcomes. Such processes in themselves supported learner wellbeing.

The processes used removed the time burden inherent in Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga. We saw that a pattern of regular small “bites” of attention interwoven within the course provided the seamless embeddedness we were after. This different process also enabled many examples to be gathered together rather than just one or two. Further, our experience of mapping wellbeing outcomes to Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga’s wellbeing descriptive indicators showed that a mapping process, including an expanded and evolving set of indicators in response to a diverse learner population, could be routinely undertaken if approached systemically.

Outcomes

The wellbeing outcomes we found, which we clustered as accomplishments, relationships, self-worth, belonging, independence, and optimism, both aligned with and extended the Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga framework; in that sense, the results supported our initial aims. The Māori learners in the Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga study identified 16 personal, cultural, and whānau relationship wellbeing outcomes. Similarly, our current study, encompassing diverse learners, found personal and family-related wellbeing outcomes to predominate as well as exhibiting some differing emphases (e.g., on official markers of accomplishment). The overlap and variation we saw across the two research studies suggests that a meaningful set of indicators with potential to resonate with all L+N learners will be dynamic and ongoing. The outcomes also pointed to interlacing relationships between elements in each outcomes cluster and across clusters as well as a strong influence of contextual features on these relationships and outcomes. Further discussion of the role of context and multiple dimensions of these outcomes can enrich our understanding of L+N learning and its meaning in learners’ lives.

First, a number of learners spoke positively and proudly about their accomplishments in terms of L+N skills. They ranged from being able to use commas in personal shopping lists to obtaining a recognised level certificate in L+N. Some of these experiences may not be considered particularly important in the broader society because they may be construed as a basic everyday activity, but they are a significant part of learners’ lives. These kinds of accomplishments may serve them in several ways. Skills improvement and certificates attest to learners’ social competence and help challenge the keenly felt stigma they carry for being labelled as low literate—an unfortunately well-known stigma throughout New Zealand society. Skills accomplishments do enable greater autonomy in learners’ everyday lives. Thus, strong emotional wellbeing is related in this way to improved literacy skills. Moreover, learners reported increased self-worth and an improved self-image as a result of the small class sizes, individual attention, and dedication of their tutors.

Learners reported more effective ways of communicating to others, accompanied by enhanced relationships within the family, with community groups and agencies, and in commercial and public encounters. Learners attributed this new competence to class discussions, observations of others’ interactions outside of class, tutor modelling of patient supportive communication styles, and explicit instruction about effective ways of communicating. They reported that more competent communication led to greater calmness, better relationships, and improved interactional outcomes for themselves.

As noted earlier, a sense of connectedness and belonging is important in Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga, in Pacific people’s notions of wellbeing, and it is a highlight of wellbeing outcomes among the diverse learners in this study. Learners across the four programmes identified a sense of belonging and inclusion, a sense of caring, and even family-like closeness in their groups. In our view, these findings are largely attributable to the tutors’ caring approach and patient dedication to each learner’s progress, along with the welcoming organisational structure of the programmes. Small classes, the friendly accessibility of programme managers, allowance for offspring to accompany parents when necessary, and opportunities to visit classes before enrolling were all mentioned by learners. All this meant that learners felt safe, were not afraid of losing face, and worked together supportively. The sense of connectedness was not limited to the class community; it extended to learners’ family lives, which figured importantly to them, as in the Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga study. Some tutors shared aspects of their own family life in class. Learners’ enhanced communication contributed not only to better relationships but also to belonging. What was learned in the L+N programmes flowed on to family when L+N learning was passed on to family members, served as inspiration to children, and made family members proud.

Most importantly, the outcomes reported in the study were multifaceted and interlaced, linked with the learners, the tutors, the programme content, and the context. For example, literacy skills achievements led to greater sense of self-worth and positivity. Improved communication was related to improved relationships and sense of belonging. Tutors’ supportive approach created a sense of safety and willingness to try things. These findings will seem unsurprising to experienced L+N tutors and educators, but they seem much less acknowledged in the broader discourse about adult L+N education.

We see these in-progress trends as understandable, for outcomes arise through each learner’s changing capabilities and context, including life and school experiences, knowledge, skills, circumstances, resources, and relationships brought with them to the L+N programme and experienced in the classroom. We need also to consider the features of the current study. Learners’ willingness and ability to reflect on and articulate outcomes varied. The tutors’ concepts of wellbeing and effectiveness at integrating attention to wellbeing also varied.

Finally, the small numbers in the study meant that the data showed what is possible but not necessarily the limits of possible outcomes or what outcomes are predictable.

We feel confident in constructing guidelines for continuing to build on this research in other L+N programmes. These will be outlined in the following section on implications and recommendations.

Implications and recommendations

1. Next development step for a wellbeing framework. This research highlights the importance adult L+N learners and their tutors place on the broad outcomes that accrue for them and their families from their L+N learning, beyond their gains in L+N skills alone. Alongside skills outcomes, broad outcomes are important to learners because they are connected to aspects of their lives that matter to them. When identified, they provide a more complete picture of the benefits of their L+N learning which, accordingly, includes skills gains as well as enhancements in wellbeing. The data showed that wellbeing outcomes can be identified and recorded through straightforward classroom processes in an ongoing and regularised way. We recommend that

L+N tutors are encouraged to pay attention to wellbeing outcomes that accrue for learners from their programmes and to try out the processes used successfully in the study to identify and record them (conversations, mind mapping, and journaling).

2. Organisational support for attention to wellbeing outcomes. The research showed that tutors bring a range of content, assessment, and relational skills and knowledge to the programmes they teach. Attention to learner wellbeing is already present. The programmes already have inherent demands and expectations of content coverage and outcomes reporting, linked to learners’ goals and programme aims. Specific or greater attention to wellbeing outcomes would suggest some changes to practices to accommodate such increased attention. Where providers wish to increase their attention to wellbeing outcomes, we recommend that:

- there is demonstrable organisation-wide valuing of wellbeing outcomes that are important to the learners in their everyday lives

- tutors have, and feel they have, space and time to include attention to wellbeing outcomes in their programmes and to reflect on their wellbeing outcomes-related practice

- tutors have opportunities to develop:

- understanding of the diverse and varying influences that may shape learners’ lives

- understanding of wellbeing concepts and their manifestation

- ways to encourage learner reflection and linking of L+N learning to what is important to the learners.

-

3. Maintaining caring, respectful, strengths-based relationships as the guiding ethos. Respectful and caring relationships between tutor and learner and among the whole class group were founded on whanaungatanga, manaakitanga, trust, reciprocity, and tutor belief in learner strengths. These relationships provided the context for attention to wellbeing outcomes in this research. Warm tutor–learner and learner– learner relationships were central, led by the tutor. Tutor capacity to establish genuine caring, respectful relationships and ways of relating provided the foundation for programmes that could pay attention to and deliver wellbeing outcomes. We recommend that:

programmes focus on quality of relationships alongside quality of content and content delivery in order to achieve optimal learning and wellbeing outcomes for their learners.

4. Establishing the valuing of wellbeing outcomes from the outset. An important feature of these programmes was the way learners could establish learning goals that mattered to them early in conversation with programme staff. This whakawhanaungatanga process provided opportunity from the outset for programme staff to make clear the value they placed on learners achieving outcomes important to them. We recommend that:

all adult L+N programmes follow initial practices that begin the building of strong relationships with learners and that demonstrate valuing and facilitate establishment of learning goals that are valuable to them in their everyday lives.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for the programme managers’, tutors’, and learners’ gracious welcome into their organisations, their classrooms, and their lives over the past 2 years. The critical insight and participation of our partners at Literacy Aotearoa, Bronwyn Yates, Peter Isaacs, and Katrina Taupo, was invaluable. We also thank Bronwen Cowie and the staff at WMIER and at NZCER for their support on this TLRI project.

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 109–137.

Barton, D., Appleby, Y., Hodge, R., Tusting, K., & Ivanič, R. (2006). Relating adults’ lives and learning: Participation and engagement in different settings. London, UK: NRDC.

Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanič, R. (2000). Situated literacies: Reading and writing in context. London, UK: Routledge.

Baumgartner, E., Bell, P., Brophy, S., Hadley, C., His, S., Joseph, D., Orril, C., Puntambekar, S., Sandoval, W., & Tabak, I. (2003). Designbased research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 32(1), 5–8.

Blissett, W. (2011). Hei puāwaitanga mō tatou katoa: Flourishing for all in Aotearoa: A creative inquiry through meaningful conversation to explore a Māori world view of flourishing. Prepared for the Mental Health Foundation of New Zealand. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.nz/assets/ResourceFinder/Flourishing-for-all-in-Aotearoa-Hei-Puawaitanga-Mo-Tatou-Katoa.pdf

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Durie, M. (1998). Whaiora: Maori health development (2nd ed.). Auckland: Oxford University Press.

Edwards, R., (2009). Introduction: Life as a learning context? In R. Edwards, G. Biestra, & M. Thorpe (Eds.), Rethinking contexts for learning and teaching (pp. 1–14). Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Fenwick, T., & Landri, P. (2012). Materialities, textures and pedagogies: Socio-material assemblages in education. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 20(1), 1–7.

Furness, J. (2013). Principles and practices in four family focused adult literacy programs: Towards wellbeing in diverse communities.

Literacy and Numeracy Studies, 21(1), 35–57. http://doi.org/10.5130/lns.v21i1.3329. Available at: https://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ journals/index.php/lnj/article/view/3329

Hutchings, J., Yates, B., Isaacs, P., Whatman, J., & Bright, N. (2013). Hei ara ako ki te oranga: A model for measuring wellbeing outcomes from literacy programmes. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa.

Karacaoglu, G. (2012). Improving the living standards of New Zealanders: Moving from a framework to implementation. Wellington: The

Treasury. Available at: https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2012-06/sp-livingstandards-paper.pdf

Literacy Aotearoa. (2018). Literacy Aotearoa annual report 2017. Auckland: Author. Retrieved from: http://www.literacy.org.nz/sites/ default/files/documents/LAReports/20170719-Literacy-Aotearoa_Annual-Report.pdf

Mark, G. T., & Lyons, A. C. (2010). Maori healers’ views on wellbeing: The importance of mind, body, spirit, family and land. Social Science & Medicine, 70(11), 1756– 1764.

Māori Adult Literacy Working Party. (2001). Te kāwai ora: Reading the world, reading the word, being the world. Report of the Māori Adult Literacy Working Party. Wellington: Te Puni Kōkiri.

Ministry of Education. (2001). More than words: The New Zealand adult literacy strategy. Wellington: Author.

Nelson, G., & Prilleltensky, I. (2010). Community psychology: In pursuit of liberation and well-being (4th ed.). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

OECD. (2013). How’s Life? 2013: Measuring Well-being. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. Available at: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/ economics/how-s-life-2013_9789264201392-en

Potter, H., Taupo, K., Hutchings, J., McDowall, S., & Isaacs, P. (2011). He whānau mātau, he whānau ora: Māori adult literacy and whānau transformation. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Rogers, A., & Horrocks, N. (2010). Teaching adults (4th ed.). Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

Shah, H., & Marks, N. (2004). A well-being manifesto for a flourishing society. London, UK: New Economics Foundation.

The Treasury. (2018). Our people, our country, our future: Living standards framework: Background and future work. Wellington: Author. Available at: https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-12/lsf-background-future-work.pdf

Publications associated with this project

Accounting for the full value of learner outcomes 2019

Research Briefing Year Two

Research Briefing Year One

Prioritising people from skills to wellbeing ACAL 2018

Pushing back at accountability policy reframing adult literacy

Investigating wellbeing related outcomes NZARE 2018

Building on Hei Ara Ako ki te Oranga NZARE 2017

Education Colloquium presentation 2017

Education Colloquium presentation 2018

Questioning social media 2019 TLRI 9166