Ko te pae tawhiti whäia kia tata:

Ko te pae tata whakamaua kia tina

Continue seeking to bring distant horizons closer:

Consolidate what you have achieved

1. Introduction

This study focuses on the “assessing” aspect of tertiary teaching in a distance teacher education programme. It explores the perceptions of the role of written assessment feedback held by a cohort of students enrolled in The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Diploma of Teaching (Early Childhood Education (a Level 7, distance teacher education programme using mixed delivery methods).[1]

Effective teacher education improves educational outcomes for learners in tertiary institutions (student teachers) and for end-user learners (children) in schools and early childhood services. This project explores the role that written feedback (from lecturers to student teachers, after assessment of their work) plays in the learning and support of these students. The findings relate strategically and practically to other teacher education programmes – such as online programmes – by giving teacher educators a greater understanding of the nature and extent of written assessment feedback. Such feedback is likely to support student teachers to continue and complete their programmes and to lead them towards greater understanding of key concepts and enhanced skills. Studying aspects of lecturer feedback practices may stimulate discussion, reflection, and, possibly, modification of tertiary teaching practice (Nuthall, 2002).

The research context

Because the study explores the impact of written assessment feedback for distance learners, it is important to review the role of written assessment issues in distance education and consider their effects on students. Key literature on these issues framed the development of aims, objectives, and research questions for this study.

Assessment and feedback

Feedback to students, whether oral or written, is a crucial aspect of the assessment process, and therefore must be considered within a broader assessment and teaching framework (Gipps, 1994).

The term assessment is defined by Black and Wiliam (1998) as:

all those activities undertaken by teachers, and by their students in assessing themselves, which provide information to be used as feedback to modify the teaching and learning activities in which they are engaged. (p. 2)

Assessment can be formative, summative, or a combination of both; it may also include selfassessment. While assessment of learning (summative assessment) remains central for employers, the public, and policy makers, there is growing acceptance of the potential benefits of assessment for learning (formative assessment) through the feedback loop (Higgins, 2004). In reality, there are both summative and formative elements in most feedback. This is illustrated through the widespread practice of tutors giving comments on written assessment tasks. While these comments are primarily formative, many ultimately have a summative purpose.

Higgins (2004) reminds us that the important point to remember about feedback from formative assessment is that it must help students to learn. It must also form part of a continuous cycle of learning. To do so, it must not only give students an indication of their achievements, but, crucially, provide them with information and guidance from which they can learn (Brown, 1999; Ding, 1998; Higgins, 2004). In doing so, feedback also has an important motivational function (Hyland, 2000).

Biggs (1999) argues that meaning is constructed through learning activities, that teaching and learning must be about conceptual change, and that how students are assessed influences the quality of their learning. Therefore, it is important to ensure that curriculum assessment procedures and teaching methods are aligned, so that curriculum objectives relate to higher order cognitive thinking, which leads to students becoming autonomous and reflective learners who have learned how to learn (become deep learners) (Hyland, 2000). Black and Wiliam (as cited in Higgins, Hartley, & Skelton, 2002) note that students are active makers and mediators of meaning within particular learning contexts. They emphasise the importance of interactions between teachers, pupils, and subjects for learning within “communities of practice”. Formative assessment, an important part of this alignment, provides feedback to students and gives tutors a way of checking students’ constructions. Students are provided with a means by which they can learn through information on their progress.

Within the “communities of learning” associated with higher learning institutions, there are complex interrelationships and power differentials at work between students and tutors that temper student approaches to teaching and learning (Higgins, 2004). Ecclestone and Swann (1999) highlight the social power and status of assessment in relation to students’ anxieties over grades. They suggest that attempts to improve learning through formative assessment will be mediated by tutors’ and students’ cultural and social expectations of their roles, and their earlier educational experiences. Given the complex relationships and sensitivities that surround assessment, this is difficult territory for even the most skilled tutor to navigate.

Mackenzie (as cited in Higgins et al., 2002) identified that written comments were often the major source of feedback for students. He notes that written feedback is becoming prevalent in all institutions, as the landscape of higher education becomes characterised by greater reliance on online teaching and increased workloads for lecturers. The time available for face-to-face meetings between student and lecturer is diminishing, and there is greater reliance on written correspondence (whether paper based or electronic).

It is clear that written assessment feedback has a key role to play in the enhancement of student learning. This TLRI project contributes to research in this field by identifying:

- the barriers that may undermine the potential effectiveness of feedback; and

- what kind of feedback is likely to help students engage most effectively with learning.

Assessment feedback in distance education

Learner support is an important element of any teacher education programme. It is particularly important for learning and course completion in distance education, although what counts as support varies (Robinson, 1995). It may include tutoring, counselling or advising, facilitating, supporting, and assessing.

In distance education programmes, lecturers have more limited opportunities to model and foster positive class and peer relations, question and challenge, set up simulations, and so on. Communication on assessment is a key opportunity for distance education lecturers to influence learning outcomes, by:

- providing feedback about gaps in knowledge;

- providing direct instruction relating to skills;

- providing content knowledge;

- explaining key concepts in different ways;

- using questioning to encourage students to reflect on and explore concepts;

- reinforcing good information or argumentation when it has been provided; and

- setting expectations.

Lecturers working in a distance learning programme spend a higher proportion of time commenting on students’ scripts and providing written feedback than those whose teaching involves face-to-face delivery. The feedback process uses tools such as reflective questions, positive comments on points made, the provision of additional points to support student arguments, the correction of points made, and suggestions for further reading to enhance students’ understanding.

Effect of assessment feedback on student learning

Meta-analyses of effective teaching (for example, Gallimore & Tharp, 1990; Hattie, 2002) show that teacher practice has powerful effects on student outcomes. Effective teachers actively involve students in their own learning and assessment. They make learning outcomes transparent to students. They offer specific, constructive, and regular feedback. They ensure that assessment practices impact positively on students’ motivation. Alton-Lee’s (2003) best-evidence synthesis on highquality teaching for diverse students in schooling suggests that when assessment takes the form of effective and formative feedback, it is one of the most influential elements of high-quality teaching.

Effective feedback is a key teaching influence on learning outcomes, because it functions to promote ongoing improvement (Brophy, as cited in Alton-Lee, 2003). It also has an important motivational effect on student learning through reinforcing effort and providing recognition of achievement (Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, as cited in Alton-Lee, 2003). However, Alton-Lee (2003) notes that negative evaluation or feedback without scaffolding to resource and support student learning can have a negative effect on students’ motivation and engagement, and may contribute to student disaffection. Williams (2005) differentiates between supportive feedback and corrective feedback, claiming that while both are necessary, it is corrective feedback that leads to behaviour change. Higgins et al. (2002) found that formative assessment feedback was essential in encouraging the kind of “deep” learning desired by tutors.

The identification of barriers that undermine the potential effectiveness of written assessment feedback, together with the lack of research in this field, provides a strong argument for further research on the nature of feedback for students that instils a “deep” engagement with their subject. Weedon (2000), when examining the congruence at The Open University between lecturer and student understanding of the intended meaning of feedback, found a high level of alignment between the two groups, and recommended more research on this topic. The areas she identified for particular consideration included the role and characteristics of written feedback in the co-construction of students’ learning.

There appears to be little international or New Zealand research on students’ perspectives on the use of formative written assessment feedback. This is despite the significant position that written feedback comments occupy in students’ experiences and the widespread belief today that the purpose of assessment is to improve student learning (for example, Gipps, 1994; Higgins et al., 2002).

2. Aims, objectives, and research questions

Aims

The aims of this research were to

- add to the knowledge base about tertiary teaching and learning, particularly assessment practice in tertiary distance education;

- enhance the links between educational research and distance teaching practices; and

- strengthen research capability among lecturers involved in early childhood teacher education.

Objectives

The specific objectives were to:

- examine students’ views on how the extent and immediacy of feedback supports their study and/or extends their learning;

- identify the characteristics and methods of the feedback that students find most effective in supporting their study and/or extending their learning;

- examine whether student progress and retention are linked to student views on effective feedback approaches for supporting and/or extending their learning; and

- involve ECE lecturers in the research process to enhance their appreciation of evidence-based teaching practices and to build their research capability.

Research questions

- How does the extent and timing of assessment feedback to distance learners support study and extend learning?

- What is the nature of the feedback that students find most effective for motivating continued study and/or extending their learning?

- Why is this particular kind of feedback most effective?

- Is there a link between student characteristics (for example, level of study or on-job experience) and their perceptions of the effectiveness of different feedback strategies for supporting study and/or extending their learning?

Research value

TLRI projects are required to address the following principles (Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, 2006):

- address themes of strategic importance in New Zealand;

- draw on related international work and building New-Zealand-based research evidence;

- be forward looking;

- recognise the central role of the teacher in learning; and

- be undertaken as a partnership between researchers and practitioners.

A priority of strategic importance addressed by this project was “understanding the processes of teaching and learning”. The project aimed to increase understanding of an important aspect of pedagogical practice in distance teacher education, through its focus on the role of written assessment feedback in supporting and/or extending adult student learning. Pedagogical understanding of assessment feedback is relevant to other education providers, including distance education, teacher education, and tertiary providers.

On a broader front, the timing of this project is strategically important, given that it supports Pathways to the Future, the early childhood strategic plan (Ministry of Education, 2002), which requires all early childhood teachers to have a Diploma of Teaching (Early Childhood Education) by 2012. Teaching within Diploma of Teaching (ECE) courses must be motivational and effective to ensure that this upgrade is achieved within the designated timeframes.

Distance education supports the government agenda to increase the number of qualified staff in early childhood education services, through providing an accessible training option to students who may not easily be able to access other training options – for example, rural students, students in paid employment, students who are parents, and students without transport.

Writing on ways in which early childhood education training can be made more open and inclusive, Moss (2000) suggests that training which enables workers to go at their own pace is likely to be an important component of teacher training in the future. Distance education is also a preferred option for those Māori and Pasifika students who prefer the anonymity of distance study (Research Evaluation Consultancy Ltd, 2001, 2002). In line with this goal, increasing our knowledge of what constitutes effective written feedback for student learning will contribute to increased retentions and completions in distance teacher education. Thus this project also links to the strategic priorities of “reducing inequalities”, “addressing diversity” and “exploring future possibilities” (Teaching & Learning Research Initiative, 2006).

Within The Open Polytechnic, the project will contribute to a growing research culture. In the light of research-based funding systems and the value placed on higher qualifications, it is important that staff not only undertake research, but see themselves as competent to do so.

3. Research design and methodology

First, it is important to give information on who the research participants were, and the specific context of the programme in which they were enrolled, because the overall programme philosophy includes approaches to assessment and student profiles. Decisions about paradigm, methodology, and methods of the study were influenced by this programme context. These aspects of the research design are discussed, as are consideration of ethical issues and theoretical tensions.

Participant information

Research participants

Students who enrol in The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Diploma of Teaching (ECE), Level 7, must be at least 17 years of age, but the majority are in their 30s or 40s. The “typical” (but not universal) student profile is of a mature woman with family responsibilities who works in an early childhood centre.

The programme has academic entry criteria and a rigorous selection process, so as to ensure that the prospective students are suitable for becoming teachers. The programme is a three-year, full-time, degree-level course that encourages students to be reflective and self-motivated. Students can live anywhere in New Zealand. They do written work by distance, complete practicum and home centre requirements close to home, and attend workshops at regional locations.

To qualify for inclusion in this research project, the students had to be enrolled in the selected course and have received feedback from at least five assignments. This was to ensure that participants had received a sufficient amount of feedback to be able to comment on the experience.

Relationships

The Diploma of Teaching accreditation document states that the programme is based on the belief that personal and professional relationships between lecturers and students reflect the centrality of relationships in teaching and learning, and are modelled through the programme (The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand, 2002). Lecturers in this programme have a regional cohort of students whom they support throughout the three to six years of the programme. They were keen to engage in a study that would enhance the student voice and experience.

While research tasks were mostly undertaken by the research team, the research project was seen as belonging to the Centre for Education Studies. All regional lecturers were involved at key points in the research process; they worked on the ethics proposal application and the questionnaire and focus group design. Section 5, “Building Capability and Capacity”, discusses participatory aspects of the research project, and ways in which it supported the development of a research culture.

Programme information

Philosophy of the programme

The early childhood teacher has a key part to play in ensuring that “children grow up as competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society” (Ministry of Education, 1996, p. 9).

The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand’s Diploma of Teaching (ECE) programme is grounded in the belief that all children are active learners, and that they are entitled to education that recognises and provides for their individual abilities, strengths, and challenges, whatever their cultural, social, political, and economic backgrounds. The adult’s role as teacher and learner, and as a model for and a facilitator of children’s learning, is vitally important (see, for example, Rogoff, 1990; Smith, 1996; Vygotsky, 1978).

It is essential that early childhood education teachers work supportively in a reciprocal and responsive manner with both children and adults, and in close partnership with parents, caregivers, whānau, and communities. Such relationships and partnerships serve to strengthen and empower the early childhood education setting, the family, and the wider community. The diploma programme provides student teachers with a sound understanding of the holistic nature of learning and development, and the diverse and individual ways in which infants, toddlers, and young children learn and develop.

The pohutukawa tree, growing within the context of the wider environment, has been adopted as a metaphor that reflects these values and beliefs, while conveying the importance of the growing child, the growing student teacher, and the environment for learning.

The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand’s Diploma of Teaching (ECE) programme is of mixed mode, including both distance and face-to-face components. The programme comprises three main areas,: reading materials, workshops, and practicums. The assignments and activities for each course are completed by distance, while the workshops and practicums are the face-to-face components. Students who study full time complete the programme in three years. In this time, each student also completes 14 weeks of practicum and 30 days of face-to-face workshops. The workshops cover a wide range of topics that complement the learning during the courses.

There is a strong process focus on developing student teachers as competent practitioners and critical thinkers. The mixture of learning modes and processes in the programme ensures that student teachers develop critical thinking that is practical, reflective (involving research, complex concepts, and analyses), reasonable, and results in a belief or action (The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand, 2002). Ennis’s (1987) taxonomy of critical thinking dispositions and abilities underpins the course design.

The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand sets up supportive relationships with student teachers to scaffold their learning. Lecturers provide environments where dialogue can occur. Feedback loops foster positive attitudes towards continuous learning, through:

- reflection about student teachers’ own practice, based on reading;

- reflective questions posed in course materials, and reflective journal entries while on practicum;

- regional lecturer feedback, both face to face and by email; and

- feedback and grades when assessing student teachers’ written assignments.

The Open Polytechnic Diploma of Teaching (ECE) endeavours to promote early childhood education as “not just about effective ways of learning how to implement new policies and make changes. It is also about legitimacy and power in the wider system, beyond the early childhood setting” (Carr, 2001, p. 180).

Assessment and feedback

The courses are designed for sequential completion, with programme-wide “threads” (such as bicultural issues) running through each course. Students generally complete two assignments per course. Courses are semesterised. Within semesters, students plan their own timetable for completing assignments, on the basis of the number of courses in which they have enrolled, and employment and personal commitments. There are few set dates beyond the end-of-semester date. Students are encouraged to send work in regularly, so that they receive ongoing feedback. Margrain (research in progress) suggests that students appreciate this flexibility – for many, it is a key reason for enrolling in the programme. Many students choose to study one course at a time and send in all of the work for that course before moving on to another.

Regional lecturers in the programme have specialist areas of expertise and assess students’ work within their areas of expertise. Thus, all courses are effectively supported by their lecturers and lecturer workload is spread fairly.

There is a system for ensuring that assessment is fair, valid, and consistent. The assessment regulations approved by the Academic Board state that all new courses must have a clear statement of the learning outcomes for the course, how these outcomes will be assessed, the standard of performance expected of the student, and the criteria for achievement of the course learning outcomes. Across the programme, moderation processes ensure that students’ work is assessed consistently. The first three scripts assessed by new markers are cross marked by another lecturer, and from that point cross marking occurs on 10 percent of scripts.

Assignment requirements and performance criteria are clearly stated in the information given to students when they start their course. This information includes how and to what standard the outcomes will be assessed, the summative assessment procedures for the course, the grading or marking system that will be used, and the level of competence expected.

Formative assessment activities allow students to practise the skills and knowledge on which they will be tested during summative (achievement-determining) assessment activities. Formative assessment activities are student directed. Methods and strategies commonly used in formative assessment include student-marked (self-marked) assessments with questions and answers provided, and phone calls or emails to a regional lecturer or specialist marker.

Summative assessments measure performance against the learning outcomes and standards prescribed for the course. Students are provided with assessment criteria as a guide to completing the task.

Technically, by focusing more on the skills and elements in applying knowledge within a given context, the assessment of abilities increases the construct validity of the task while reducing the quantity of testing required to achieve a reliable assessment (Clift, 1997, p. 11).

In the diploma programme the primary means of providing students with feedback on their work and general learning support are the written comments on their script, and a feedback letter accompanying each piece of returned work. Because most students do not have regular face-to-face contact with regional lecturers, it is important for the written feedback to:

- give specific technical guidance where needed

- identify strengths and weaknesses in the student’s work

- provide recognition of the student’s effort and achievement

- encourage the student to continue with his/her study

- recognise the student as an individual. (The Open Polytechnic, 2002, p. 26)

Assessment feedback should also explain how the content of the student’s work meets the learning outcomes of the assignment, and suggest where to find additional information.

A standards-based model of assessment is used, whereby the feedback is included on a generic feedback letter that covers the four elements for which marks are awarded. These areas include content (50 percent), supporting evidence (30 percent), structure (10 percent), and presentation (10 percent). Criterion referencing fits into each grade level of this model to provide clear, fair, and consistent descriptions of the multiple variables that need to be considered, assessed, and pulled together (Wolf, as cited in New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 1991) to provide sufficient evidence to infer competence at a particular level.

Students in The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Diploma of Teaching (ECE) are required to demonstrate competence in all learning outcomes, which means they must pass all assignments (gain at least 50 percent). Work given a grade of 40–49 percent may be resubmitted for a maximum grade of 50 percent, but there is only one opportunity for resubmitting work for each course.

Because of the importance in maintaining student motivation of returning work promptly, turnaround time is important. The standard performance indicator for turnaround time at The Open Polytechnic is 10 working days from receipt in the faculty to return to the mailroom.

Research design

Epistemology and paradigm

Interpretivism is an epistemological perspective that is relevant to this study, because it holds that facts and values are not distinct, and findings are inevitably influenced by the researcher’s perspectives and values. It is thus not possible to conduct entirely objective, value-free research, although the researcher can declare and be transparent about his or her assumptions (Snape & Spencer, 2003, p. 17).

The researchers acknowledge that their own values may have influenced the interpretation of the data, but this influence was alleviated in two ways. First, the facilitators of the focus groups were independent of the programme. Secondly, and as a result of the pilot study evaluation, the language used in the questionnaire was adjusted to be more meaningful for participants.

This study includes elements of both participatory and constructivist paradigm positions (Lincoln & Guba, 2000). Links to the participatory position include:

- “goodness of quality criteria”, where the understanding comes from more than one source (questionnaire and focus group discussions) with purposeful research that will lead to positive change;

- “values”, where the focus group input is valued;

- “inquirer posture/voice”, where the primary voice of the student is manifested through completion of the questionnaire and participation in focus group discussions, even though the researchers have chosen the primary voice; and

- “training”, where Dr Anne Meade assumes a role of mentor/support, input from the advisory group is valued, and the researchers are working as a team, with each research team member contributing their individual skills (Lincoln & Guba, 2000, p. 170–171).

The constructivist paradigm position is also evident in our research. To support this view, the study is looking at what is real, what is useful, and what has meaning for students (Lincoln & Guba, 2000) in relation to feedback, through the interpretation of interviews and questionnaires. Lincoln & Guba (2000) suggest that making sense of the findings will shape action, which in this instance will lead to improved practice by lecturers. Denscombe (2003, p. 76) states, “The crucial points about the cycle of inquiry in action research are (a) that the research feeds directly back into practice, and (b) that the process is ongoing” (italics in the original). Because of its participatory nature, therefore, this study reflects some elements of action research, particularly when the practical recommendations from the findings are implemented in future practice.

The research is “mixed research”, including both quantitative and qualitative methods. The questionnaire was composed of multiple closed questions (quantitative) and several open-ended questions (qualitative), whereas the focus group interviews provided solely qualitative data. According to Cresswell (2003), current research practice, rather than be simply quantitative or qualitative in nature, focuses on the continuum between the two. Burns (2000) concurs, and comments on the need for both approaches, “since no one methodology can answer all questions and provide insights on all issues” (p. 11).

Methodology

The key methodology of the study is survey research. This form of research is particularly useful for studies that want to find out something (including thoughts, values, and attitudes) about or from a particular group of people, and is widely used in educational research (Fowler, 1993; Keeves, 1997; Neuman, 1997; Seale, 2004; Williams, 2003). According to Denscombe (2003), survey research includes the characteristics of “wide and inclusive coverage”, research that is undertaken “at a specific point in time”, and “empirical research” (p. 6).

The methods used were:

- a postal questionnaire, sent to all students enrolled in the programme who had completed at least five assignments;

- three focus-group interviews; and

- analysis of student records.

Students could participate any or all of these aspects of the research, or could decline to take part.

Ethics approval for the research was provided by the Joint Ethics Committee[2] in March 2003.

Research methods

Questionnaire

A 13-page questionnaire was developed (see Appendix 1), based on literature relating to the research questions. The questionnaire included closed and open questions. The development of this instrument was informed by feedback from regional lecturers, The Open Polytechnic’s TLRI Advisory Committee, the Ethics Committee, and a statistician. A pilot of the entire survey process was completed before the final survey commenced, feedback from which influenced the questionnaire’s presentation and language in particular. The pilot sample was chosen by selecting every numerical multiple of a particular number from the master list of eligible students.

All students who had completed five or more assignments and who had been active within the past year (excluding those who had received the pilot) were sent questionnaires. However, further into the semester a review of the master list highlighted that a number of students had withdrawn or not proceeded with their enrolment, meaning that they had now been inactive for two or more semesters.[3] These students were subsequently deleted from the master list, reducing the number of eligible students who had been sent questionnaires to 237.

Strategies for enhancing the return rate included: two sets of reminder letters; verbal reminders at workshops, study groups, and other times when lecturers were in contact with students; and two notices in the student newsletter. In addition, spare copies of questionnaires were provided at two programme workshops. These strategies supported the return of 125 questionnaires with signed permission forms,[4] a return rate of 53 percent.

The questionnaire was presented in the form of a stapled booklet, printed on green paper with a logo representing “wise” research. The colour coding and logo were also used for the reminder letters and feedback to students. Questionnaires were despatched by mail (see Appendix 1), along with an information sheet (Appendix 2), consent form (Appendix 3), and reply-paid envelope. The returned questionnaires, consent forms, and questionnaires were coded with a matching number. The numbers were allocated in order of date of receipt, beginning with A1 for questionnaires received before written reminders were sent out, B1 for questionnaires received after reminder but by the requested date, and C1 for questionnaires received after the requested date but in time to be included in the research analysis.

Focus groups

Focus groups provided an opportunity to discuss issues raised in the questionnaire in greater depth. Three focus groups were formed: one of students of Māori descent, and two general groups. Of the two general groups, one comprised students from an urban area where regional lecturers are accessible,[5] and the other was made up of students from a provincial area where no regional lecturer is based. Once the locations were identified, all eligible students within the relevant geographic areas were invited. Group size ranged from 6 to 15 students.

Focus group questions (see Appendix 4) were compiled after a preliminary analysis of the questionnaire had been completed. People who had knowledge of the programme, but who had not been markers for the courses in which students were enrolled, facilitated the focus groups. Dr Anne Meade provided training in focus group facilitation for the facilitators and also the wider lecturing team, as professional development in research.

Two of the focus groups were held on a Saturday afternoon, and one on a Monday evening. Attendance ranged from 1 to 7 students. The meetings took between 1.5 and 2 hours, including “meet and greet” time. Refreshments were provided, and petrol vouchers for reimbursement of travel. Students had been posted additional information forms for the focus group phase (see Appendix 5), and signed additional consent forms at the focus group (see Appendix 6). For two of the focus groups, the numbers attending were lower than desired (n = 1 and 2), but more students (n = 7) attended the third focus group.

Each focus group was managed by two facilitators, one of whom facilitated the discussion while the other recorded written notes and provided support. The facilitators held a debriefing session immediately after the focus group meeting, and notes were prepared promptly. A further debriefing session for all three focus group meetings, attended by one facilitator from each focus group, was held within a few weeks.

Student records

When completing the consent form for participation in the questionnaire, students were asked if they also consented to their academic records being accessed. For those who provided permission, academic results (course completion dates and grades) were examined, giving a measure of comparison between achievement and questionnaire responses. Particularly useful variables from the academic records were grade and pace (see under “Qualitative analysis”, below).[6] It was hypothesised that these factors may affect the value students placed on their written feedback, their reflection, and their motivation.

Data analysis

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data were manually analysed using thematic analysis, in particular “constant comparative analysis” (LeCompte & Preissle, cited in Mutch, 2005). The steps used in this approach to analysis include:

- perceiving;

- comparing – same as/finding similarities;

- contrasting;

- aggregating and labelling;

- ordering;

- establishing linkages and relationships; and

- speculating – tentative theorising.

Sections of qualitative data from the questionnaires were analysed by three of the research team, each of whom searched for emerging categories from the data. The three researchers collaborated to ensure that labelling and categorisation were consistent. The focus-group data were analysed by one researcher, also using the thematic analysis approach. Two of the research team worked together to review questionnaires from students who identified as Māori, in order to consider issues of particular relevance to this group of students. The full research team provided feedback and discussion on the themes for each data set.

Quantitative analysis

Statisticians from the New Zealand Council for Educational Research constructed two variables from questionnaire and academic records:

- pace – the speed at which students are working through the required courses. The three categories created were: slow, medium and fast; and

- achievement – the letter grades of students. The three categories created were: low, medium and high.

Pace was constructed by identifying the number of courses each student had completed (passed with A, B, or C grades). It represented the number of courses passed in total, divided by 1 for Year 1 students, by 2 for Year 2 students, and by 3 for Year 3 students.[7] This gave a well distributed variable (Appendix 7 gives tables showing excerpts from the data) that could be usefully transformed into the three categories: slow, medium, and fast.

An overall achievement variable was created by taking, for each student, the total number of A passes multiplied by 3, the total number of B passes multiplied by 2, and the total number of C passes multiplied by 1. These were added together and divided by 1 for Year 1 students, by 2 for Year 2 students, and by 3 for Year 3 students, to form a common scale across all students. This variable also had acceptable distribution (see Appendix 7 for an excerpt) and could be grouped into low, medium, and high.

The statistical procedures used in relation to these two constructed variables showed acceptable dispersal across the pace and achievement categories (see above) for each year group. The two constructed variables were useful for cross tabulating against other survey responses.

Ethical issues

It is important in any research project to consider ethical issues. In this project, we were particularly mindful that our students were being invited to participate, and that it was important that they did not feel imposed on or coerced. Information letters clearly stated that participation was voluntary.

A second ethical issue for students was that we asked for access to their student records. It was important that students understood that all research information would remain confidential, and that the records data would be aggregated, rather than attributed to particular individuals.

There was extensive discussion within the research team and the polytechnic’s TLRI Advisory Committee about who would facilitate the focus groups. Early in the project, it was envisaged that regional lecturers would be invited to participate, as part of our focus on building research capability. The TLRI Advisory Committee wisely suggested that this might compromise the data, in that students would be more likely to speak frankly about their assessment feedback to people who were not themselves markers in the programme. For this reason, we arranged for facilitators who knew about the programme content and philosophy, but were not current or previous markers of the courses. We offered training in focus group facilitation skills for regional lecturers, in order to contribute research support to our wider team.

We firmly believe that the participants should benefit from the research. The students have all been sent interim feedback. A copy of the final report will go to all participants who are currently enrolled, as well as to those who have since left the programme, but who indicated on their permission forms that they would like to receive a copy of the report. In addition to providing feedback, this shows students that their lecturers are also learners. We also have an ethical obligation to discuss and consider findings from the research, in terms of how we can improve our pedagogical practice and institutional systems to support students as well as possible. We intend to do this in a forum at an internal conference in March 2006, and by providing copies of the report to strategic staff within our organisation.

Theoretical tensions

The underlying philosophy of the Diploma of Teaching (ECE) programme claims to be sociocultural (The Open Polytechnic, 2002). While some aspects of the programme (such as workshops, practicum, home centre requirements and formative assessment) fit into the sociocultural realm, the programme also includes other central aspects that are constructivist rather than sociocultural. These aspects include the use of summative assignments. The assessment procedures are governed by procedures that are used in the wider Polytechnic throughout other courses, and by the mode of study, which is distance learning. The researchers therefore acknowledge that there is a tension between the philosophy of the programme and the assessment procedures. In addition, there is a strong programme commitment to building relationships with students. These supportive, nurturing relationships, however, are in tension with unequal power relationships – including the ability of lecturers to grade and fail their students.

Within our research project we aimed to support sociocultural philosophy and use a participatory paradigm. Because of practicalities, however, we used a questionnaire that was largely quantitative. In some respects the tension between our use of quantitative method and our desire to qualitatively interpret and understand the data mirrored the tension within the programme. To some extent this was mediated by our use of additional qualitative methods (the facilitation of focus group interviews, and the open-ended questions in the questionnaire) and by our consultation with many parties in the creation of the questionnaire (including the pilot process).

4. Findings

Discussion of the research findings is divided into four sections. The first deals with student profile and progress, including demographics, reasons for studying, and the constructed variables of pace and achievement. The next three sections – content of feedback, systems, and motivation – cover themes that emerged from the data. Students raised four issues dealing with the content of feedback: support to improve; change over time; justification of grades; and reflection and links from theory to practice. In the “systems” section, students discussed script return, consistency of marking, their own understanding of the written feedback provided, and how it was useful to them. The final section considers issues linked to motivation: the type of feedback given; the use of grades; and relationships.

Student profile and progress

Demographics

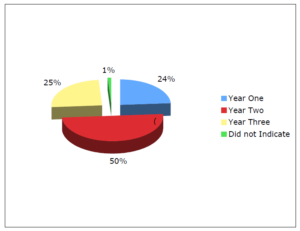

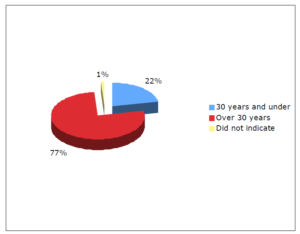

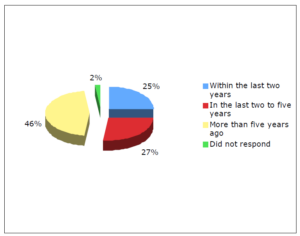

The students participating in this study were asked to identify their year of study, age, ethnic group, first language, how long it had been since they had undertaken study before enrolling in the programme, and their highest qualification, both at school and since leaving school. Information was also collected from their student files held at The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand. Student profiles are shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3 and in Table 1. The majority of students in this programme were over 30 years of age and had last studied more than 5 years previously. It is important for organisations such as the Ministry of Education and the New Zealand Teachers’ Council to consider the views of this group of mature learners. Student teachers in other institutions may be dominated by younger students, such as 18–20-year-old school leavers.

Figure 1 shows that half of the research sample consisted of Year 2 students. This can partly be explained by the fact that the Diploma of Teaching (ECE) is a recently accredited programme growing in size each year, so that there are more students in Year 2 than Year 3, and more in Year 1 than in Year 2. However, those Year 1 students who had not yet received feedback from five assignments at the time of the study were not eligible to participate.

Figure 1 Year of study

Figure 2 Age of participants

Figure 3 How long since study was last undertaken before entering Diploma of Teaching (ECE) programme

The survey asked students to identify their first language (see Table 1). These results were cross tabulated with their year of study. Students with first languages other than English were more numerous in Year 2

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| English | 30 | 100.0 | 49 | 77.7 | 27 | 87.1 |

| Pacific Island | 0 | 3 | 4.8 | 1 | 3.2 | |

| Other | 0 | 11 | 17.5 | 3 | 9.7 | |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 31 | 100.0 |

Reasons for studying

The main reasons for deciding to study for a Diploma of Teaching (ECE) were personal. A total of 91 percent of all students (100 percent of Year 1 students) said the love of children was a very important or important reason for studying, and 90 percent said their wish to be an early childhood teacher was very important or important to them. The impact on individuals or ECE centres of government regulations relating to staff qualifications was rated as an important or very important reason by 50 to 60 percent of those who answered the survey. There were no significant differences between students at different year levels for any of the reasons cited.

While the number is not statistically significant, it is worth noting that a higher proportion of Year 3 students said that studying for a qualification was important or very important for keeping their jobs.

Pace and achievement

Data from students’ academic records held at The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand were analysed using the constructed variables of pace and achievement. The results are given in Table 2 gives the results of pace, by year level; Table 3 shows achievement, by year level; and Table 4 shows pace, by achievement.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| Slow | 14 | 46.7 | 10 | 16.1 | 0 | |

| Medium | 14 | 46.7 | 42 | 67.8 | 21 | 72.4 |

| Fast | 2 | 6.7 | 10 | 16.1 | 8 | 27.6 |

| Total | 100.0 | 62 | 100.0 | 29 | 100.0 | |

N/R = 3; df = 4; Chi-square = 22.86; p < 0.0001

The higher the year level, the greater the proportion of high achievers. However, the increase in pace across year levels cannot be accounted for simply by poorly achieving students dropping out of the programme, because there were relatively high completion rates at all levels.[8] No Year 1 students in the sample had gained a D or E grade (none of these failing students chose to complete the questionnaire).

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| Low | 8 | 26.7 | 8 | 12.9 | 0 | |

| Medium | 17 | 56.7 | 47 | 75.8 | 22 | 75.9 |

| High | 5 | 16.7 | 7 | 11.3 | 7 | 24.1 |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 29 | 100.0 |

Cross tabulation of the two constructed variables, pace and achievement, resulted in an association that is statistically significant. High achievers are moving through their courses at a faster pace than low achievers. There are important implications here for tertiary study policy, including teacher education. Students benefited from having less than a full-time load in their first year while they learned the programme expectations. Assessment feedback contributed to their growing understanding of required conventions, underpinning philosophy and technical skills. Assessment feedback is particularly relevant for this particular cohort of students, many of whom had not studied at a tertiary level before. Students were then able to pick up the pace and manage a greater number of courses while achieving good grades. Their success is particularly remarkable, given that most were also working and supporting families. Thus it is important that once students are “flying” we respect their ability to make decisions about their workload – increasing workload does not necessarily correlate negatively with grades. It is, however, critically important that students are well supported in the early stages of their programme, and that our structures are not so rigid as to require students to complete a 3-year programme in equal thirds.

| Low achievement | Medium | High achievement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| Slow pace | 12 | 75.0 | 12 | 14.8 | 0 | |

| Medium pace | 4 | 25.0 | 65 | 75.5 | 8 | 42.1 |

| Fast pace | 0 | 9 | 10.5 | 11 | 57.9 | |

| Total | 16 | 100.0 | 86 | 100.0 | 19 | 100.0 |

df = 4; Chi-square = 6.11; p < 0.0001

Using the student record data, the constructed variables were also cross tabluated with written feedback variables. The researchers found that technical aspects of written feedback were significantly associated with both pace and achievement. Those who said that these aspects of feedback were very important and useful to them were likely to be both fast paced and high achievers.

Content of feedback

The researchers have referred to two categories of feedback: global feedback and technical feedback. Feedback in relation to sentence structure, paragraphing, essay format, APA referencing, and presentation is defined as “technical” feedback. All other feedback is referred to as “global” feedback.

The study showed that there is a general consensus that all written feedback, both technical and global, plays an important or very important role in helping students to improve their written work. It also aids in providing the links from theory to practice that are so important in a teacher education programme. Studies of undergraduate university students undertaken by Hyland (2000) and Orsmond, Merry, and Reiling (2002) found that students believed strongly in the potential value of written feedback, copnsidering that it not only enhanced both motivation and learning, but also encouraged reflection and clarified understandings.

Progress

Results from the survey showed that for over 80 percent of the students all written comments (global and technical), whether on the script or in the feedback letter, were most informative, and were considered to be important or very important in helping them to improve their work.

It helps to see where I need to improve … helps me to learn something new or look at something in a different way. (Questionnaire[9])

Ticks on the script were important or very important for improving work for 63 percent of students surveyed.

The ticks on the script are interesting. Most markers use them to emphasise agreement and put ticks over relevant phrases. I like this simple strategy. (Questionnaire)

However, 34 percent felt neutral or considered ticks not at all important:

Ticks on the script give you confidence but they don’t help you to improve. I had a module with ticks everywhere and only got a B+. If my work was so good, why didn’t I get an A? (Questionnaire)

Many students, both in the survey and in focus group interviews, reported that they found the feedback on technical aspects of their writing to be extremely useful. Such feedback reportedly “taught” essay structure, paragraphing, APA referencing, sentence structure, grammar, and spelling:

Referencing correctly. It was helpful because I didn’t repeat my mistakes and therefore I could learn to reference almost perfectly. (Questionnaire)

I found feedback very helpful on structure of essays especially when I first started. [My lecturer] was really good at telling me where things go, and grammar too. Now I know. In the early stages it’s really good. (Focus group[10])

Conversely, some students felt that feedback focused too much on technical aspects, and was “picky” and pedantic:

I received high grade (90–95 percent) but was dismayed as to why small technical aspects were highlighted by the tutor. (Focus group)

One marker focused on four full stops in my assignment – couldn’t see the value in that. (Focus group)

Students found feedback on assignments that required resubmission to be positive and supportive, and felt that they were given specific guidance on how to pass:

Feedback comments are outlined clearly on areas required to resubmit. Usually the marker gives clear explanation on what they want us to cover. (Questionnaire)

I found the resubmit feedback very helpful. The marker clearly explained what needed to be done before resubmitting my assignment. (Questionnaire)

No students stated that feedback was “not important”. There appear to be statistically significant differences between year level groups in relation to the usefulness of feedback to students (that is, whether “important” or “very important”), although these relationships are non-linear. A large majority of Year 1 students rated feedback as “very important”. There is a drop in the percentage of Year 2 students saying this; the percentage increases again for Year 3 students.

There were some differences in the way feedback was used by different year levels and ages of students. Advice about presentation (a technical aspect of feedback) was considerably more important for Year 1 students than for the more experienced. Older students (over 30 years) appear to differ significantly in their use of the comments on the script to improve future assignments.

Table 5 and Table 6 illustrate the importance of “global” feedback and “technical” feedback respectively to the different year levels.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| Important | 1 | 3.3 | 24 | 38.1 | 9 | 29.0 |

| Very important | 29 | 96.7 | 9 | 61.9 | 22 | 71.0 |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 31 | 100.0 |

df = 2; Chi-square = 15.8210; p < 0.0004

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| Important | 0 | 15 | 23.8 | 4 | 12.9 | |

| Very important | 30 | 100.0 | 48 | 76.2 | 27 | 87.1 |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 31 | 100.0 |

df = 2; Chi-square = 9.0658; p = 0.01

The literature suggests that there is enormous variation in whether, and to what extent, tutors respond to students’ writing. Assessing students and providing feedback result in divergent practices, characterised by variations in the qualitative and quantitative comments that tutors provide on course work assignments (Ding, 1998; Higgins, 2004; Hounsell, 1987). These assessment practices may vary from being authoritarian, judgemental, and detached (Connors & Lunsford, 1993) to being personal and empathetic.

Change over time

Students reported that feedback changed as they progressed in the programme – the feedback they received at the beginning differed from that received midway through or towards the end. Students mostly indicated that this was appropriate and reflected responsiveness to their changing needs. Whether the feedback was more affirming at the early or later stages may depend on individual student competency:

I guess as we move on in levels I expect that the comments will get more challenging. (Focus group)

Now the comments have changed because I’m learning. (Focus group)

Written feedback at the beginning of the programme was more informative compared to later in the programme … more corrective than supportive [towards the end]. (Focus group)

Some aspects of feedback may not have changed; students referred to ongoing encouragement and affirmation, and also to the consistent nature of comments:

The comments have remained positive as I’ve moved on. (Focus group)

Repetitive comments from lecturers from assignment to assignment. (Focus group)

Studies suggest that many students experience difficulties with written work in their first year, that they have difficulty knowing what tutors want, and that different tutors within the same discipline may have different requirements. These difficulties are compounded for students moving between courses, who find different conceptions (depending on the discipline) of what essays and essay writing are about. This experience can lead to anxiety and uncertainty (Drew, 2001; Hartley & Chesworth, 2000; Hounsell, 1987; Hartley, 1980; McCune, 1999).

Justification

It is clear that students want justification as to why they receive a particular grade, especially if the grade is low. They felt at times there was inconsistency between affirming feedback comments and the lower grade received:

Sometimes the comments may be glowing, but then the mark is 6 out of 10 …. markers don’t say why you got 6 out of 10. (Focus group)

If all comments are positive, then why don’t the marks reflect positive? (Focus group)

Justification of the grade is personally vital for my own self improvement. (Questionnaire)

Students suggested that written feedback would improve if markers were more specific, clarified points, and justified what they said or did:

When they tick sometimes a comment, as they think that aspect is important, or they could expand on why or how they agree or disagree is helpful. (Questionnaire)

Always show how marks could be improved. I consistently read that my work is very good but I don’t see this in the mark. How do I get the extra 20 percent? Needs feedback for improvement. (Questionnaire)

Orsmond et al. (2002) noted that students seem to be frustrated by feedback that identifies their weaknesses, but does not tell them how these might be addressed. Students also showed a desire for guidance in advance of assignments, to help them to know what tutors expect and what particular assignments require of them. These responses suggest that feedback that is merely judgemental and evaluative rather than developmental may be seen as of limited use by students who want to know how to improve (Higgins, 2004).

Reflection and links from theory to practice

Many students commented on the links between assessment feedback and their professional practice as early childhood teachers. They acknowledged that learning was an ongoing process, not limited to particular courses:

They (the tutors) are probably looking for something different from a reflection. For example, “I’d take that waiata back to my centre and incorporate into our next programme planning cycle”. (Focus group)

I’d try and use the same terminology in my work as is used in my courses – this makes it very relevant. (Focus group)

It is important to have correct technical aspects for use in making profile books to reflect our professionalism. (Focus group)

I’m a critical thinker but I’m still learning. (Focus group)

One student reported that she had been told to “take from it what you want to” in relation to the course, which she found more empowering that trying to focus on what she thought the marker wanted (focus group).

Some students indicated that they felt uncomfortable with personal or reflective aspects of assignments being graded:

I get confused if I get asked for and give my opinion and then get a bad mark. How can I get a bad mark for my opinion? (Focus group)

They also questioned whether high academic grades necessarily reflected good quality practice:

I don’t believe that getting an “A” mark makes you a better early childhood teacher. (Focus group)

It was also noted that finding the time to be truly reflective is a challenge for busy students who work, have family commitments, and study:

Time is an issue to be reflective. (Focus group)

Systems

The Open Polytechnic has systems to ensure validity and reliability in marking. Focus group discussion indicated that students generally understand and accept these systems.

Script return

In this study the approach that students took to completing courses, and therefore assignments, affected both the way they used the feedback and its usefulness (Higgins, 2004). A submission pattern within the Diploma of Teaching (ECE) is that students often choose to submit both assignments of a course together, or soon after each other, so that they receive within-course feedback less often. They usually complete courses “one at a time” (consecutively) within a semester, rather than having “several on the go” (concurrently). Thus, by the time feedback from one course arrives, students usually have begun the next course. Over 90 percent of students responding to the survey said that it took 3–4 weeks or longer to have their marked scripts returned to them. Most considered this too long, especially if they were waiting for the feedback before starting on their next assignment:

Four weeks is too long. I start to get concerned especially if I need Assessment 1 back to complete Assessment 2. (Questionnaire)

Research by Ding (1998) suggests that students may not get enough time to act upon feedback comments. With the prevalence of modularised courses, it is likely that students may often have moved onto a new topic by the time they receive their feedback, which can limit the effectiveness of the feedback.

Survey and focus group data from this study showed that students were frustrated when there were delays in returning their work, as they appreciate being affirmed and encouraged. While some students like to wait for the feedback before starting their next assignment, they recognise that their progress would be very slow if they did wait:

I just carry on with assessments. If I waited for scripts to come back, my progress would be very slow. I deal with a resubmit if and when I get one. (Focus group)

A few students are resigned to the waiting time and have found it does not impede them:

It takes a while, but I’m only impatient to know how I have fared. I don’t find it hinders me from starting my next assessment. (Focus group)

If students do wait for feedback before starting their next assignment, it is either a requirement of the assignment task or for guidance, “because if you need to make changes to the first assignment it is pointless in starting the next one if you don’t know what the changes are” (survey).

Internal moderation processes also impact on script turnaround time, as some students find this an added delay. Some students felt that their scripts had been used for moderation more often than other students’ scripts, even though selection is generally random.

My first one was sent to mediation [moderation]. My second took ages as it was left on a marker’s desk. My third was again misplaced. (Questionnaire)

These systems do ensure inter-marker reliability. However, students still questioned the consistency of marking.

Consistency

Students perceived differences in the way markers responded to their writing. Issues of consistency between markers recur in many comments, from students’ initial thoughts on feedback to ways feedback could be improved.

Markers are all different and I don’t find it encouraging …. For example in my first year I was told to write one point per paragraph but then a marker disputed this when I put it into practice. I now wonder if I have been given the correct information in the first place. (Focus group)

Transparent criteria were also important to ensure validity and consistency in marking. Despite assessment guidelines being structured to promote consistent formative feedback, there will inevitably be pressures and scope to operate “beyond” the assessment guidelines that tutors are presented with. This positioning suggests that different teachers will evaluate work in different ways, and may give different advice and guidance. Black and Wiliam (1998) argue that these differences matter little if the resultant feedback leads to gains in learning. Students, however, prefer to see consistency between markers:

I’d been told by markers that if I’d gone over the word limit, I would have got a better mark. I’ve really resented this as I felt I had to be concise to the designated word length. I’d just be getting confident when the marker changed, and the next one has a different style of marking. My style had not changed – marker had – then my marks changed! (Focus group)

Processing feedback

The majority of students (89 percent) indicated that they open their feedback when it is first received. From survey results, 76 percent of students always or usually read it carefully, whereas 21 percent skim–read it. A large number of students (78 percent) take up to half an hour to read their feedback, while a few (14 percent) read it in less than five minutes. Questions about feedback were cross tabulated with age groups, and most of these results were not statistically significant. However, there appears to be a difference for older students (over 30 years) in relation to what they do first with written feedback: they read the feedback carefully.

A large majority (87 percent) read the mark first, but two thirds of the students (77 percent) rarely look at the mark only. Half the students indicated that they read the comments on the script last.

The order in which written feedback is read varies according to different year levels. In the case of Year 1 students, a large majority read the mark first (93 percent, compared with 80 percent of Year 3 students). General and specific feedback letter comments were read second or later by most students, with nearly 20 percent of Year 3 students going to the letter first.

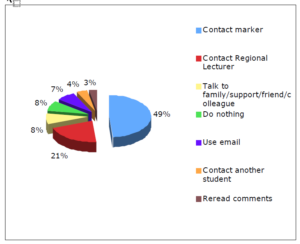

Figure 4 illustrates that, if students received feedback they did not understand, or if they had difficulty in actioning suggestions made in the feedback, their most likely action would be to contact the marker. However, only half the students said they would contact the marker; the next most likely action was to contact their regional lecturer. This highlights the value students place on the relationship they have with their regional lecturer. Zepke et al. (2005) affirm the importance of “fostering positive relationships between students and significant others in the institution” (p. 17). Some students would instead talk to family members, support persons, colleagues, or other students, while a few would take no action at all.

Figure 4 Action when feedback is not understood (by responses)

Most students indicated that they would call lecturers and markers when they wanted clarification of their work:

I ring to understand the question. (Focus group)

Students commented on telephone, email and face-to-face access to staff, but did not always say who was contacted. The telephone was a popular method, although several students commented that email was useful because they “can use it anytime” (focus group).

I find that easy, I email [my lecturer] to ask and then I can save it and read it. (Focus group)

A few students felt that they should be independent and were reluctant to call. Some “felt they should know the answer without any help” because distance students had all the materials that they needed in front of them (focus group). Other students indicated that they contacted the Open Polytechnic staff only when it was critically important. One student clarified these times, saying “at the very end” when she was desperate, or about administration issues (focus group).

Some students could not find contact numbers, or did not know whom to call, even though this information was given to them. Thus, the difficulty of contacting the organisation was more frustrating:

Sometimes it’s hard to get hold of them and when you are pressured for time, you know, you hit a problem, you want help now. It means you can’t get on with it. This is your only time to do it. (Focus group)

Tossed around and moved from person to person when contacting … by telephone. (Focus group)

Use of feedback

Learner support is an important element of any teacher education programme. It is particularly important for learning and course completion in distance education, though what counts as learner support varies (Robinson, 1995). McKenzie (as cited in Higgins et al., 2002), when studying the process of tutoring by written correspondence at the Open University in the United Kingdom, identified that written feedback comments were often the major source of support for students. Higgins et al. (2002) identified variables related to the quality, quantity, timeliness, and language of comments as contributing to students’ understandings and utilisation of feedback.

Results from The Open Polytechnic survey indicated that over 80 percent of students found all comments, whether on the script or in the feedback letter, informative.

Because the Diploma of Teaching (ECE) courses are designed to be sequential steps within a holistic programme, feedback is applicable across the programme, rather than only to specific courses. When completing assignments, a large number of students (80 percent) used feedback from a range of courses. They identified that comments on the script were important. A slightly lower percentage indicated that opening and closing comments in the feedback letter, comments on content and on supporting evidence and, to a lesser degree, comments on structure, were important.

Feedback that had programme-wide relevance was appreciated:

Will look at comments on previous assignments in a strand. There are often references that can be cut and pasted, readings that can be used and comments that help. (Focus group)

Many students discussed the ongoing benefit of knowledge gained about perspectives of learning and theories of human development. Courses with this content were positioned early in the programme, and students reported that they related their understanding to many subsequent courses. (Focus group)

Some students found that feedback given for related courses was very useful. Survey results showed that students are more likely to refer to feedback from a related course (69 percent) or to their last feedback (66 percent) when they are completing assignments, rather than feedback from courses of the same level (56 percent), or all previous feedback (46 percent). They reported “looking back”, although mostly only within particular strands of the programme. However, some content was perceived to be “more general than specific for future usefulness” (focus group).

Other students felt that feedback on one course was of minimal use to other courses. Sometimes this was due to the quality of the feedback:

If people commented useful information instead of irrelevant comments which state the obvious. (Survey)

Sometimes feedback was deemed to be of little value when a course had been completed – some students felt that feedback did not “feed forward”:

Once it’s finished, it’s finished. (Focus group)

For the students who do not wait for the assignment feedback to come back from markers before they start the next assignment, the feedback is used mainly to consolidate current knowledge and for general guidance for a wide range of other courses. Hyland (2000) and Orsmond et al. (2002) also found that the majority of their respondents claimed to read feedback comments and to use them for subsequent assignments.

Motivation

Survey findings showed that students’ initial thoughts about the purposes of written feedback concerned, first and foremost, its use for improving their work. The next most important purpose concerned motivation to continue their study:

I find the written feedback useful and encouraging. (Questionnaire)

Feedback is so important. It gives me the confidence to tackle the next assignment. (Questionnaire)

Students also indicated that particularly helpful comments in written feedback were those that motivate:

I believe students like myself need specific comments that we can identify, understand and act on …. Also, it is encouraging to receive comments that are amusing or just encouraging eg: yes, you have a good point here. Or ‘ka pai, well done’. (Questionnaire)

In line with these findings, Higgins’s (2004) research suggests that feedback should help students to learn. This belief is also supported by Hyland (2000), who highlights that feedback is an important motivator.

Type of feedback

The survey data found that for 90 percent of students comments on improving work, identifying strengths and weaknesses, and explaining how learning outcomes were met or not met were important or very important in motivating them in their study:

For a resubmit, the marker clearly told me what I had to do to meet the learning outcome. It is very helpful. It motivates me to continue my study. (Questionnaire)

Comments relating to the structure of their work were important or very important for motivating 81 percent of the students. Fewer students (66 percent) identified comments relating to the presentation of their work as important or very important for motivation. Ticks on the script were important or very important for motivation for 59 percent of students. These indicate that feedback is a very important vehicle to motivate students in their study, and that helpful comments relating to global feedback are motivational. However, some technical feedback may not necessarily motivate. Gallimore and Tharp (1990) and Hattie (2002) support this finding by stating that specific and constructive feedback assures that assessment practices impact positively on students’ motivation. Motivation comes from positive comments:

All constructive criticism I have received has been given in a positive manner and I appreciate that. (Questionnaire)

Motivation is also internal to the student. One student commented that the positive feedback “makes me want to do better” (survey). Ultimately, however, it is the student’s “own reasons for finishing the course” that are the motivating factor. Alton-Lee (2003) notes that negative feedback can have a negative impact on students’ motivation and engagement, whereas Orsmond et al. (2002) note that negative as well as positive feedback is likely to motivate students to develop a greater understanding of their subject. However, they say that a statement of weaknesses must be accompanied with an explanation of how to address them.

Table 7 shows that, in relation to motivation, global feedback (as opposed to technical feedback) is perceived to be very important by more students studying in Year 1 than in Year 3, and by the fewest in Year 2.

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | (No.) | (%) | |

| Important | 0 | 13 | 20.6 | 3 | 10.3 | |

| Very important | 30 | 100.0 | 50 | 79.4 | 26 | 89.7 |

| Total | 30 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 29 | 100.0 |

N/R = 2; df = 2; Chi-square = 7.8503; p = 0.02

One possible explanation for the non-linear patterns could be that more Year 2 than Year 1 or Year 3 students already hold a tertiary qualification, and are more confident about undertaking tertiary study. They are also different from other year groups, in that 18 percent of them seldom or never read the feedback carefully (compared with 13 percent of students studying in Year 3 and none in Year 1).

Grades

There are strong links between grades and motivation in the survey. The results show that 81 percent of students find that the grade becomes a motivating factor when it is accompanied by justification of why it was awarded. Students suggest that markers should “justify the grade given. I enjoy my work being critiqued so that I can improve” (questionnaire).

Yet some of these comments also make a link between motivation and grades. For example, previous feedback is used:

As motivation to try harder and achieve higher grades. (Questionnaire)

For personal motivation and to see if I have passed. (Questionnaire)

Positive comments are always good on feedback sheet even if the mark you got wasn’t that good. (Questionnaire)

In the focus group discussions, it was revealed that for some students written feedback provides motivation to get a higher grade, whereas for others, completion of the programme is their focus.

With a slightly different emphasis, Swan and Arthurs’s study (1998) takes the view that grades are the prime motivator for students. However, they go on to say that feedback is linked to wanting to know how to make improvements to raise the mark. The findings from this research study do not support the belief that grades alone are the prime motivator.

Findings from the present study also highlight factors that “demotivate” students. These include negative comments, inconsistent feedback, repetitive feedback, feedback without purpose, and untimely feedback. Timeliness of feedback is a point supported by Gibbs (1999), who argues that this has a significant impact on motivation.

Relationships

Students also commented that when their work was marked by people with whom they had a relationship, the comments were more meaningful. They also felt less confident about contacting markers with whom they did not have a relationship. One student said that she was more likely to take “on board” a marker’s written feedback if she knew the marker personally, rather than if the marker were anonymous.

When you know them it’s like having a photo to go with the name and the comments are more real. Especially when you have to ring them up. (Focus group)

Getting to know the tutor makes studying easier. For example, personalised comments. (Focus group)

It would be good if we could just meet. It just helps. I’ve met a few of them [regional lecturers] – then they know you and you can gel with them. It would be nice if you could meet with them (all). (Focus group)